(#510: 10 September 1994, 1 week)

Track listing: Rock ‘N’ Roll Star/Shakermaker/Live Forever/Up In The Sky/Columbia/Supersonic/Bring It On Down/Cigarettes & Alcohol/Digsy’s Dinner/Slide Away/Married With Children

Here’s something else you can do for me. Take off those rose-tinted sunglasses of smug hindsight. Possibly the most overvalued gesture of the critic, music or otherwise, is the one which argues: no, this isn’t any good now, it is of its time, you had to be there. Balls. The reason these albums are appearing in this blog at all is because they were considered good, or even great, then, and we have to evaluate them as such. Don’t stare back at things with your quite unearned sense of superiority because you supposedly know so much better now. It is what took you, what sent you, at the time, in its time.

I had been wondering how to tackle this album and then found myself thinking of Raw Deal, Bothwell’s number one punk band (not that there was much, i.e. any, competition) at the time when punk was happening. This is because there is currently a wee discussion going on about them on Facebook and my old school chum Ross Phillips posted a lovingly crude video of the band standing in some allotments, miming to Sham 69’s “Borstal Breakout” (Sham 69, you chortle. How uncool! How out of keeping with 6 Music/UNCUT’s Rich Tapestry! Oh, shut up and go listen to That’s Life, their extraordinary – yes, I said extraordinary – concept album from 1978. When “Hurry Up Harry” was in the top ten, which is more than most punk singles managed, we schoolkids used to sing the chorus in French. “Nous allons á la MAISON PUBLIQUE!”).

Raw Deal lasted until about 1980 and two of its number, the McCluskey brothers, subsequently resurfaced in the ranks of belated number one hitmakers The Bluebells. That is substantially longer than punk, as such, lasted – was Radio Clyde’s punk show Street Sounds, presented by Brian Ford, even still on air in 1980? But other liaisons matured, and most of them came to fruition in the garage-cum-rehearsal space of Andrew “Storky” McGurk. Meanwhile, over the other side of the M8 motorway in East Kilbride, we heard tales about a guy yelling like Lydon on Metal Box and another guy banging a huge oil drum who called themselves The Primal Scream; about a couple of doss brothers who never got out of bed and had to be reminded what year it was – three years later, their malfunctioning guitar speakers started giving out uncontrollable feedback during a gig, and Alan McGee and Joe Foster yelled that’s BRILLIANT! Keep it IN! (Reader, I was there. I was that third shouter who told the Mary Chain about AMM.)

Then I think of “Blues From A Gun” from the never-heralded but nevertheless superb third Jesus and Mary Chain album Automatic, and how firmly it stands as a direct precursor to Oasis, he said finally linking up these inchoate reminiscences with the album under consideration. Of course it is; how could it not be? Two noisy, eternally-arguing brothers – naturally McGee would go up to Glasgow, witness Oasis and discern Mary Chain II.

Like the Mary Chain, Oasis did not merely know their rock history; they were pre-emptively part of it. As with Psychocandy, Definitely Maybe overthrows that other weary critical bat of “don’t tell everybody about it - DO it, and THEN tell everybody.” Sod that, we only have so much time on this planet. Oasis wasted no time telling everybody that they were the fucking best, and you believed them, don’t lie to me, smugpants. Mozart was in the habit of saying that he was the best composer alive, and was proved right. Sometimes a little modesty is the hugest arrogance.

This alleged bigheadedness worked because the young Oasis were so damned earnest about things. Definitely Maybe is the work of a band who, at the time of its making, essentially didn’t have a bean to rub together between them. Therefore, singing with stinging confidence about being a rock ‘n’ roll star to three winos and a dog in an indie pub is in its way the most rock ‘n’ roll gesture one could make (I remember seeing Orange Juice in some scuzzy pub on the south side of Glasgow in 1980; it must have been the Mars Bar because Edwyn had to dodge flung pints of beers and unceasing yells of “F*CK OFF YA P**FY C*NT!” Mind you, the support band were subjected to similar treatment; they were four kids from Dublin, barely out of school, calling themselves U2. I wonder what happened to them…).

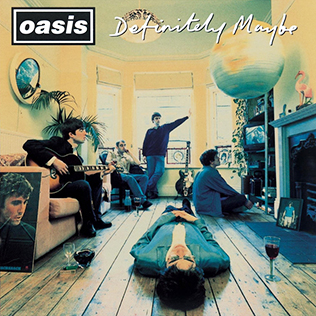

The early sound of Oasis is the bracingly liberating sound of young people with, literally, nothing to lose. The album cover, staged in Bonehead’s front room, suggests a certain classicism – photos of Rodney Marsh and George Best, spaghetti westerns on the TV, a large portrait of Bacharach – but Oasis really are unashamed romantics posing as archivists.

For a long time I considered writing this entry as a double with The Holy Bible by The Manic Street Preachers, which was released on the same August Bank Holiday Monday and bought by me from Bond Street HMV on that day, but sold merely a fraction of Definitely Maybe’s double platinum (and counting). But, on listening back to the latter, I do not really feel the need to do so, and suspect that doing so might undermine a rather important commonly-held trust. The Holy Bible is an astonishing, elemental record which rubs its listeners’ faces in uncomfortable truths, ones which palpably hit home to the musicians themselves (or, at any rate, one of them). Many at the time also found it unlistenable, and it is not an album that I choose to revisit with any great frequency, even though I would never get rid of it.

Yet the point of Oasis was that they were speaking for, and to, their community, one which had been purposely overlooked by the music media in favour of knowledgeable student types who would have got the Manics’ Plath and Pinter references straightaway. There was a quite widespread feeling that “rock” was deliberately not talking to “us,” was going over “our” heads. The Holy Bible is a desperate, if unbearably brilliant, lecture (the lyrics of “P.C.P.” would not really be out of place on the average Jamiroquai album – and that is meant as a compliment) – but Definitely Maybe tears open the curtains of doomy reserve and allows the light to flood back into lives.

You might agree with those who say that “Rock ‘N’ Roll Star” was the only song Oasis ever need have done – it sums everything up; their ambitions, their hopes and their justified presumptions. It rocks, to baptise a cliché, like nothing else had done in the previous five years or so – it busts open the door on which “I Wanna Be Adored” had been patiently knocking – and by evolving into punchbag drone noise at its climax indicate how much they owed to the sonic totality of My Bloody Valentine; apart from his exceptional free guitar work on the live version of “I Am The Walrus,” which appeared as a B-side to the single of “Cigarettes & Alcohol” and can also be found on the second CD of the three-CD 2015 deluxe edition of the album (I duly upgraded), this experimental tendency is not one which Noel Gallagher has really chosen to pursue. Why, he would immediately argue, should he? Oasis’ ”Walrus,” recorded in Glasgow, is one of the best Beatles tributes there is.

This really is powerful music. “Shakermaker” indicates not just how much the band owed to their Manchester antecedents, but a Springsteen-style eagerness to pick and mix from the best of pop “history” (to a point; the writers of “I’d Like To Teach The World To Sing” subsequently sued for and won royalties). “Supersonic,” also their debut single, commences with a downward scrape of guitar plectrum like de-riveted bolts announcing its business as surely as the “1-2-3-4!” which began “I Saw Her Standing There.”

Laura was not impressed when the video for “Supersonic” premiered on ITV’s The Chart Show one snoozy Saturday lunchtime. “FFS, not another Charlatans ripoff,” she proclaimed. Well, as far as Mancunian influences go, Shaun Ryder permeates the body of “Supersonic” quite comprehensively – one could argue that Oasis were simply finishing the job that Happy Mondays had started but were too out of it to see through to fruition – and while there is also the hint of Tim Burgess about Liam Gallagher’s vocal style, as well as a sardonic, iron confidence which puts him in a direct line from Lennon…

…actually the Manchester singer whom Liam Gallagher reminds me of, above all others, is Howard Devoto. The same cigar store Indian motionlessness on stage, the subtle are-you-tough-enough stare of challenge, and the same defiant, almost sneering monotone of vocal grain – then again, Liam’s firm avoidance of the vibrato and preference for the long-held rhetorical drone is a folk trick immediately familiar to those who know their Martin Carthy (Out Of The Cut, 1982; go hunt it down). But Liam’s focus is anti-art, anti-artifice. If he regarded himself as a work of brutalist modernism, his act wouldn’t wash.

No, Oasis bloody well mean it, just as firmly and stubbornly as Richey’s Manics did. Consider “Live Forever.” Step over Noel’s Alan Green-esque comments on all that Kurt nonsense to find that this is a song screamingly in favour of life, a song which rages against death in all of its forms. The People didn’t want clever arty curlicues; they wanted “We see things they’ll NEVER see!,” the one line on this album which speaks to them above, and more directly than, any of the other ones. We have to try harder, are made to work harder, weren’t given it on tap at birth, and because we come from the North and have to go to the South, we therefore know twice as much as those from the South who never have to come up to the North, and we know and feel things much more vividly. It is an enormous “NO!” to those who would prematurely remove themselves.

Nothing in 1994 rock – the British sort, anyway (we didn’t know about Twice Removed at the time; it never got a UK release) was as explosively dynamic and euphoric as “Up In The Sky,” an unapologetic serial scraper of skies which runs out with as much cheek and joy as your average school day hundred-metre race, and is lyrically a virulent anti-Conservative diatribe. Likewise, “Columbia,” which evolved from various jams based on Acid House classics, demonstrates that a truer indie-dance fusion can be achieved by means of osmosis as opposed to sloppy cutting and pasting – the spirit is gently and gradually mutated into this escalating, circuitous vortex of partially-bemused wonderment.

“Bring It On Down” is so damn-you-indie-torpedoes propulsive – sorry, Dodgy and Shed Seven, but you are not even in the running here – that it is only belatedly that you realise that it is an Iggy and the Stooges tribute. Yes, “Cigarettes & Alcohol” knocks off “Get It On,” until you remember that “Get It On” is structurally a knock-off of Chuck Berry’s “Little Queenie.” Moreover, it becomes clear that the aptest comparison point for Oasis is not The Beatles, or even Slade, but The Faces – there’s that same drunken camaraderie, the identical certainty that what they’re playing is greater than anything that comes before or after it, and what do they really care anyway, Sunderland 1 Leeds United 0, etc. (Rod Stewart himself covered the song in Faces style in 1998, thereby proving this point).

Furthermore, relish Liam’s “soon-she-IIIIEEEYNE!”s and “siit-tew-eh-SHEEEYUN!” – he doesn’t give a toss whether you like it or not, why should he care, he’s not singing for you, take it or leave it and so forth. If you can’t abide his jive there are plenty of underachieving Scott Walker wannabes with degrees available. Again, listen to him, if you can: “Is it worth the aggregation to find yourself a job when there’s nothing worth working for?” That sentiment connected deeply with its intended audience, who otherwise felt that they were constantly being sneered at.

“Digsy’s Dinner” is a momentary stocktaking comedic breather which still manages to harbour an element of ominous doubt in its chorus (“These could be the best days of our lives/But I don't think we've been living very wise”). Yet “Slide Away” might constitute the record’s finest six-and-a-half minutes – it sums up the album’s central message that we, you and I, have to get away from, escape, this future-free dump of a place, take the risk, talk to that woman at the bus stop, go places, form a band, do anything, anything to flee the dead end that they have scheduled for you. Guitars – so many of them - have rarely sounded mightier, and its unending finale attains a catharsis which I find acutely moving. Yes, The Smiths, yes, R.E.M., yes even Suede, yes especially Neil Young and Crazy Horse (this album is not so much Tonight The Night as There Will Be No Other Fucking Night, LIVE IT), but this is an epic of self-ordained freedom. The door is there to be opened. It’s up to you and me to open it.

And, as for all that Kurt nonsense, Definitely Maybe has Nevermind in its bones. The closing signoff, “Married With Children,” happily rearranges the chords of “Lithium” and grins its so-what-if-I’m-insolent-WHO’S-WATCHING farewell.

Smug hindsight

be sodden. Definitely Maybe was, and is, a phenomenal pop record, and a

reminder that it is one of our core duties as human beings to carve our way out

with any raw deal with which we might have been issued at our genesis. “The

Roses meet the Mondays, oh ho ho,” hissed the 1993 Christmas Melody Maker.

Oasis proved better and more durable than both. Admit it.

(To the memory of Kenneth Scott – gonna live forever.)