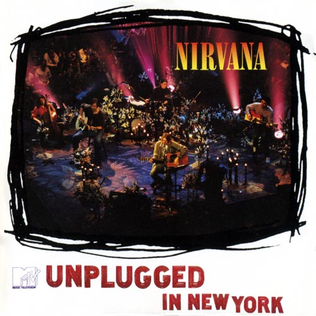

(#516: 12 November 1994, 1 week)

Track listing: About A Girl/Come As You Are/Jesus Doesn’t Want Me For A Sunbeam/The Man Who Sold The World/Pennyroyal Tea/Dumb/Polly/On A Plain/Something In The Way/Plateau/Oh Me/Lake Of Fire/All Apologies/Where Did You Sleep Last Night

Kurt Cobain was our Elvis. No, screw it, Elvis was their Kurt Cobain. You know whom I mean by “them.” The settlers for twelfth-best. The obedient centrist compromisers. Those who regarded the MTV Unplugged franchise as a contemporary equivalent of a Stalin show trial, with previous rock dissenters proclaiming that they were all now sobered up, had been saved and were penitent for their hitherto untoward animation. The producers and bankrollers of MTV Unplugged, who were horrified at the prospect of Nirvana not playing their biggest hit and also introducing and playing songs by 1994 mainstream unpersons (uh, the Meat Puppets? Can’t we get, you know…Tori Amos? Or Eddie Vedder? Or…Goddam Soul Asylum?). Who wanted them to perform a fucking encore after “Where Did You Sleep Last Night,” a performance which can only be succeeded by a semi-numbed silence.

You know the scenario, or can easily look it up if you don’t – Cobain was on cold turkey and nervous as a lake of precipitant fire about having to do this performance. Lilies, black candles and a chandelier decorating the stage set, as though rock were in the process of being buried. Six cover versions, all of which address death in differing manners. An acoustic guitar which Cobain fed through a concealed amplifier and pedals (rather like Derek Bailey used to do).

But if this is Nirvana’s equivalent of the middle section of Elvis’ 1968 TV special, then it is the young, unknowing but fearlessly enthusiastic Elvis who inhabits the centre stage of Kurt’s mind. There are times when, listening to “About A Girl,” you might be witness to the first music that has ever been made.

Unlike almost everybody else in “rock” – the exception being Elvis – Kurt had no side. The damn-you pseudo-camp arrogance of Jagger, Johansen and Lydon is absent, but so is the hey-I’m-just-like-you communal folksiness of a Springsteen or a Fogerty. He was the wannabe rock star whom rock – heck, society - forgot or overlooked or derided or ignored. The uncool pupil two rows from the back of the class who never puts his hand up but secretly absorbs everything, as opposed to a compliant son of the parish. The nerd who never speaks to that girl at the bus stop. The silenced minority. The Bartlebys who will politely refrain from playing ball.

He was real, as in there was never a reading list of note, but he nevertheless had the capacity and the openness to take in and accept everything, and therefore everybody. If you grew up somewhere like Aberdeen WA, or for that matter Uddingston, you had no choice but to investigate every potential escape route. For Kurt it was ELO, it was the Exploited, it was Beat Happening, it was the Meat Puppets, it was the Vaselines, it was every name politely expunged from the thinning threads of Rock’s Rich Tapestry. It was Leadbelly before corporate two-word rebranding.

“What are they tuning – a harp?”

Uddingston because it is on the other side of the M8 motorway from Bellshill, where Eugene Kelly and Frances McKee grew up. Everyone who went to school in the west Central Scotland of the seventies knows the hymn “I’ll Be A Sunbeam” and the Vaselines’ gently satirical take appeared on a hugely untrendy E.P. entitled Dying For It which emerged in the spring of 1988 and was ignored with the proviso that somehow Kurt got hold of a copy and grew to adore it. Hearing the accordion in particular is spine-tingling – Jimmy Shand on everyone’s radio – because this is music from my own backyard, my own upbringing, and it sounds ancient and profound.

(The Exploited, 1981’s least trendy band, one of whom went on, via Goodbye Mr McKenzie/Shirley Manson/Butch Vig, to become Nirvana’s occasional second guitarist onstage. Observe their Top Of The Pops performance of “Dead Cities,” recall what Nirvana did with the same template on the same show a decade later, and shiver anew.)

In “Sunbeam,” Kurt sounds mildly outraged by spiritual rejection – hence precipitating his expected descent into hell as outlined in “Lake Of Fire” – whereas his “Man Who Sold The World” sounds weary and disappointed; he encounters the man on the stairs, fails to recognise him or recognises him all too well, and wonders whether that was it. As with Bauhaus’ “Ziggy Stardust,” he sounds as though he means the song more than its author did (until about 1989, Kurt only knew the eighties Bowie and was astounded to learn that he’d done things like this before then).

And what about the Meat Puppets? Curt and Cris Kirkwood obligingly turn up for their triple – all songs taken from Meat Puppets II, as Kurt is at pains to point out – and we hear an essence of space; not vacancy, or limbo, or emptiness, but room to move, to explore, to wonder. It exists in the Arizona of the Meat Puppets, the Georgia of R.E.M., even in the Hawthorne of the Beach Boys, and is endemic to Canadian music, be it Paul Bley or the Cowboy Junkies (or indeed Neil Young; see anything on Harvest Moon or his own Unplugged album, or for that matter “Safeway Cart” on his partial Cobain tribute Sleeps With Angels, which narrowly missed appearing here). Up On The Sun, their third and best album, was the fresh blast of pacific air which 1985 so sorely required. But the “Plateau” essayed here demonstrates a sense of playfulness which is actually at the essence of music-making. Kurt is not afraid of goofy falsettos and semi-daft lyrics, and you wince only because he and they thought of it first (I said semi-daft; the young Ben Drew was also listening, and the chorus of “Who needs actions when you got words?” became the title of the first Plan B album).

The Nirvana songs, as such, are generally the more thoughtful, considered, quietly sinister ones. They too could be considered, as performed here, as the oldest music that had ever been recorded. “Polly” reminds me to wonder how everything can be traced back to the Everly Brothers (or, given the song’s subject matter, the Louvin Brothers might be the proper precedents). Lori Goldstein’s intermittent ‘cello – she has also been a member of Earth, and Earth 2 was the last album to which Kurt listened in his lifetime – provides the same Grecian chorus which had previously worked for Bob Mould and Nick Drake (and, of course, speaking of ELO, Jeff Lynne and Roy Wood). “All Apologies,” done very differently from the interpretation on Sinéad O’Connor’s contemporaneous Universal Mother, acts as a graceful signoff – from what is your conjection – with the voices slowly murmuring the closing mantra into pacific non-existence, like an eternal ocean refusing to cease, or indeed rock, its roll.

* * * * * *

“In fact, sounds unencumbered with meaning become the only catechism one can recite in a world without absolutes.”

(Linda Scher, Samuel Beckett’s Trilogy: A Study In Circles And Cycles. The University of North Carolina at Greensboro: 1967)

The song is properly known as “In The Pines” and appears to have been a melange of two other folk songs, “In The Pines” and “The Longest Train.” Bill Monroe interpreted the song one way (emphasising the “Longest Train” component) in 1941 and again in 1952, while Leadbelly – branding be damned – seems to have taken the lead for his many 1944-8 recordings of the song from a 1917 variant collected by folklorist Cecil Sharp, as well as an early recording, possibly by the Kossoy Sisters, from around 1925. The song, un-watered down, is to do with rape and decapitation; or, if you view it under the name “Black Girl,” is the tale of a wayfaring stranger who witnesses the evil and hides in the wood in a hopeless attempt to forget it.

(the endless inter-song anxieties about “screwing this song up” – anticipation of failure does not automatically indicate avoidance of it.)

The Louisiana

accordionist Nathan Abshire then transformed the song into an aggressive Cajun refrain,

and when translated from Creole French, his version gives us the familiar refrain,

“my girl, where did you sleep last night?” As “Black Girl,” the song became a

surprisingly hard-hitting 1964 British top twenty hit for the generally mild-mannered,

ethereal Blackburn quartet The Four Pennies (whose delicate “Juliet” may well

still end up the least played of sixties number ones). The Triffids recorded the song, under the name "In The Pines," as the title track of their 1986 album, recorded in the middle of nowhere (deep within Western Australia).

The most famous of Leadbelly’s versions was the first one which he cut on a 78 disc in February 1944. A copy of this was owned by Mark Lanegan, whose 1990 album The Winding Sheet features cameos by Cobain and Krist Novoselic on his reading of what he called “Where Did You Sleep Last Night,” and it was from the latter that the Nirvana of mid-November 1993, a couple of months prior to their final (European) tour, took their lead.

* *

Listening to Monster, as I have recently had to do, it strikes me how, just as R.E.M. sounded to be in the process of turning into Nirvana, the Nirvana represented on MTV Unplugged sounded to be in the process of turning into R.E.M. In another, fairer world, Kurt would have hooked up with Stipe and gone on to well no one knows what he/they would have gone on to do.

(but remember I was talking about the Everly Brothers earlier on, and throughout this performance there is an unavoidable second voice, the voice of a man who ultimately, in the direst of circumstances, will take on and develop what Kurt elected to leave behind. In Grohl’s Church of Kurt, we may already glimpse a future, which is preferable to no future.)

What I have been gently trying to do with this piece is to steer it away from THAT. You know what “THAT” is. You can read it in a million tedious Google links. Or you can look at things and consider: Elvis and Kurt hurtled to their ends but while they were here it really was all about something called “The Music.” Some people call it the craic, others the buzz.

So, yes, “Where Did You Sleep Last Night,” as interpreted on a television stage by Nirvana, second guitarist Pat Smear and Lori Goldstein in November 1993, is the definition of the irruption for which rock had then been attempting to grasp for going on forty years. Not stylistic daring, or worship of artifice, but a sink hole into which societal and cultural politesse could silently collapse. Nobody in rock has sung better at any time before or since. And by singing I do not mean reaching the high Cs and staying there, or swimming in eddies of melisma. Kurt’s voice crackles like inadequately-interrupted electrical currents. He sounds, frankly, like me.

On his “Where Did You Sleep,” his voice doesn’t just crackle, but cracks – an absolutist crack which many might, and did, find horrifying. The central scream of “SHIVER” destroys all previous and subsequent attempts by rock to break the sky. Lennon didn’t do it, nor did Burdon, nor did Holder. They were all Paul Quinichettes to Cobain’s Lester Young.

And why does that “SHIVER” triumph? Because of what does, or doesn’t, happen in

the pause which immediately succeeds it, or (more properly) the phrase “the

whole…” before welcoming “night” and “through,” as though the world were through.

You cannot hear it on the album. You have to watch it. Those blue eyes of his

open – suddenly he is awake, and he is able to see directly through and into the

rotten hearts of all of us. Those of us who would prematurely commemorate him

with unlistenable five-CD box sets of outtakes. Who at the time said it was a

pity then went out and put Stiltskin’s corporate insult to his memory at number

one. Who at the time didn’t consider him as important as Lee Brilleaux or Dan

Hartman. Who purchased monthly music magazines which impatiently explained why

he “had to die.” All of us who were betraying his memory even before he turned

himself into a memory.

Because – what do I hear, as I hear all the way through MTV Unplugged? I hear a charming curiosity, a winning naïveté, a resonant boldness, and beyond all else a desire to LIVE. You stupid bastards – and I exempt neither Cobain nor myself from that description – that scream of “SHIVER” is a cry in favour of living! He didn’t manage to favour it in the end, and there are many cod biographies which you can read regarding such matters. But MTV Unplugged is the final formal record of a necessarily incomplete journey, as well as a fork in the road which will lead us to Medicine At Midnight, and Kid Cudi’s two Cobain tributes on Saturday Night Live.

The greatness and extinguisher of Cobain’s essence – apart from the fact that he tore up the right rule book – is that he refused to accept reality; but just as he turned from disappointment, betrayal and poverty elsewhere in his fucked-up life, on MTV Unplugged he has stared the longest train down and mocks its now non-existent power. I think that a surviving Elvis of November 1993, whose theoretical age then I am steadily approaching now, would have understood without even having been asked to do so.

“O tiny mother,

you too!

O funny duchess!

O blonde thing!”

(Anne Sexton, closing quatrain of “Sylvia’s Death,” 1966)