(#519: 28 January 1995, 6 weeks; 1 April 1995, 1 week)

Track listing: The Power Of Love/Misled/Think Twice/Only One Road/Everybody’s Talkin’ My Baby Down/Next Plane Out/Real Emotion/When I Fall In Love (duet with Clive Griffin)/Love Doesn’t Ask Why/Refuse To Dance/I Remember L.A./No Living Without Loving You/Lovin’ Proof/Just Walk Away/The Colour Of My Love

(Author’s Note: “Just Walk Away” appears only on non-US editions of the album)

Throughout 1995, whenever I wandered into the centre of Hammersmith of a lunchtime to make sundry mundane but essential purchases in shops such as Tesco’s, WH Smiths and Boots – all shops which at that time sold records, but usually to the vast demographic of people who didn’t normally buy records – I noticed the rapid turnover in sales of The Colour Of My Love album in such places; someone always seemed to be queuing up at the till anxiously clutching a copy of the CD, and that someone, without exception, was a woman of a certain age; the same generation, or the immediate forebears of the generation, which would once have screamed at the Beatles until their colours became a little too strange, then reclining back in the imaginary arms of a Tom or an Engelbert - women in whose beaten brows you could read the story of a fight against happenstance and restriction which they had unhappily lost; any inkling of freedom long since superseded by responsibility, for awkward children, errant husbands or worryingly ageing parents.

I began to think again about that other second half of the sixties, the ones which told uncomplicated, wrenching tales of betrayal and loss – “Let The Heartaches Begin,” “There Must Be A Way,” “I Pretend,” “It Must Be Him,” “Please Don’t Go” and all the rest (even “Just Loving You” is about the bottled-up frustration its singer feels about the potential Other who steadfastly refuses to notice her) – if perhaps in the way that children tell tales, but all reflecting uncomfortably real lives, real issues which wouldn’t be swept away by lysergic flying machines, an audience scared of what revolution might actually mean, all harking back to a supposedly simpler age.

“Think Twice,” conversely, doesn’t begin to pretend to hark back anywhere, even though the songs mentioned above are some of its ancestors; it is squarely set in the mid-nineties milieu of the about-to-be-abandoned lover who in a slightly different age would have been screaming at Duran Duran or Sting, with a very autumnal 1981 slate grey sheet of ominous, muffled synthesisers for its initial backing. Fittingly, names from that period contributed; thirteen years after “The Land Of Make Believe,” Andy Hill and Pete Sinfield wrote their second number one, while former Sheena Easton/Shakin’ Stevens shift supervisor Christopher Neil co-produced.

As a single, “Think Twice” proved to provide one of the slowest ever climbs to the top, reaching number one in its sixteenth week on the chart and remaining there for a total of seven weeks, with sales nudging a million and a half. It is also one of the most nakedly striking of number ones which seeks to beg the listener’s patience.

Céline’s opening verse of hushed codes of dread is very moving (“And you and I know there’ll be a storm tonight” as the synthesised storm brews in the background) and the pleading of the first chorus is akin to a quietly tormenting prayer. Open torment is almost immediately thereafter ushered in by the soft metal guitar of the record’s other co-producer and fellow Québécois, Aldo Nova. Céline immediately increases the volume and starts to growl in the second verse as though too emotionally exhausted to endure a more gradual build-up; thus the intended one-two climactic punch of “BABY” (at 3:14) and “NO NO NO NO!” (at 3:21) bears the intended unexpected effect (compare with how the Bonnie Tyler of “Total Eclipse Of The Heart” resists the urge to scream until that penultimate, calamitous “EVERY NOW AND THEN I FALL APART!” which perhaps comes as less of a shock). There exists real pain in Céline’s “look back before you leave my life,” a hook in her desperate clinging with which to hang herself if she’s not careful.

I expect that for her third, breakthrough English language album, mentors such as David Foster, Walter Afanasieff and, above all, her discoverer, manager and eventual life partner René Angélil advised her to be extremely careful. The Colour Of My Love touches most Then Play Long-friendly bases; excitable New Jack Swing (“Misled,” which is really quite thrilling and if it had been Mylène Farmer you’d have agreed with me), deluxe power balladry (“Only One Road” with its structural hints of ABBA, “Next Plane Out,” “Love Doesn’t Ask Why”), and hints of rock – hence her “Power Of Love” was much better received by American audiences in particular than the reserved Eurocentrism of Jennifer Rush’s original.

She even has a game go at converting “When I Fall In Love” into cocktail jazz (for the movie Sleepless In Seattle) and gets the great and unheard-of Clive Griffin directly into this tale (Griffin should have been a huge star from the late eighties onwards but perhaps his name militated against that. His Step By Step album is full of the bouncingly authoritative late-eighties soul-pop that I like – “Don’t Make Me Wait” in particular, the greatest record Rick Astley never made, should have been a number one and is as directly reminiscent of the sights, smells and sounds of 1988 London as “The Only Way Is Up” and “Follow The Leader.” It never quite happened for Clive, who eventually left the music business altogether, but he will unexpectedly pop up on another couple of occasions here, e.g. entry #525).

Then again, Dion arises from an essentially European, and specifically French, milieu of the dramatic troubadour, those singers who do not improvise, but rather act, project to their audience the unswervable fact that they mean this. Hence singers such as Dion appeal directly (if patiently – this album had been released in November 1993 and had been on our chart since March 1994) to the working classes, the ordinary folk who with instinctive immediacy can understand exactly what she is communicating to them.

Céline is a splendid actress. Observe how she turns “No Living Without Loving You,” in anyone else’s hands a standard Michael Bolton-style chest-beater, into something above itself by her excited growls and elisions; by song’s fade, she is not merely stating a case or pleading, but demanding this love. Likewise, she turns “Lovin’ Proof” into the realms of the feral – her lovely Alma Cogan gulp of a yelp on “get,” her devouring of “touch” crunched upon like a particularly sensuous packet of crisps.

There is also Aznavour-level profundity. “Just Walk Away” is a spectacular portrait of a collapsed soul on the point of shattering and Céline wants you to know that she sodding means it, just as Sinéad meant it and Callas did before either of them. The performance indeed draws us back towards a forgotten sixties, a sacrificed seventies. Conversely, “Refuse To Dance” is superficially dispassionate (but fundamentally wrecked, emotionally) electropop worthy of the Pet Shop Boys, complete with André Proulx’s jarringly jaunty violin, probably echoing a dignified internal combustion.

Of course the Canadian factor is crucial – those vowels on “I Remember L.A.” confirm that this could never have been the work of an American, and “Refuse To Dance” is itself fundamentally Canadian in its linear determinism. I would also point to “L'Amour Existe Encore,” the B-side of the “Think Twice” single and a demonstration of admirable restraint and control, which may suggest that Dion found, or still finds, the French tongue slightly more accommodating of her soul than the English one. But, remember – Céline was the youngest of fourteen children, raised in a poor but happy (and staunchly Catholic) household up there in Charlemagne. She knew precisely that of which she sang and those who were bound to receive, absorb and understand it.

But the forgotten sixties, the sacrificed seventies; the Voice and a music intended for her, only for her…

Or for you?

Nobody outside Bristol or the music press knew anything about Portishead in August 1994, when Dummy materialised (I hesitate to use the term “was released,” since the record is about the circumspective impossibility of any release). Its songs weren’t played much anywhere. One might have known Beth Gibbons from her cameo on .O.rang’s Herd Of Instinct (but I think that came out after Dummy) or remembered Geoff Barrow from his cameo on Neneh Cherry’s Homebrew, but really the group had no clear precedents at all.

Hence this sounded like music which drifted into visibility, seemingly out of nowhere. It had to be listened to on headphones while walking through unfamiliar, ill-lit avenues, because it displaces most senses of rationality. One’s mind conjured affluent, empty spaces – uninhabited beach huts, seventies department stores which sold nothing but car tyres and Millican and Nesbitt greetings cards, or art books which are almost but not quite readable, sunshine, immaculate whiteness, the Lewknor Junction 6 turnoff at eleven on a Thursday spring morning, the East Neuk of Fife, the peopleless mansions of Belgravia.

A dense emptiness which steadily and subtly reminds you of…not quite what you want to convince yourself constitutes the reminder. Bond, Palmer, Captain Scarlet – all red herrings, the whole bloodied lot of them.

This is somebody’s – yours? – nightmare of “the sixties.” Lalo Schifrin, fresh from Dodger Stadium, is sampled opulently on “Sour Times,” but this, as Gibbons’ grain makes abundantly clear, is blues, is folk (Anne Briggs comes to mind during “Wandering Star,” a modified Wat Tyler-era lament), is even improv (Maggie Nicols and to a lesser extent Julie Tippetts passim), is, Lord help me, Hazel O’Connor in places (specifically the funereal, Hardy-ish “Roads”). “This Could Be Sweet” – the first song Portishead ever put together – runs on divine Fender Rhodes changes marooned on a gymnasium treadmill. Something terrible has happened and it’s no use asking after it, since Gibbons understandably isn’t keen on interviews. You are obliged to sense it.

Dummy is like The Day After You Came. “Biscuit” might be one of the most sheerly frightening pieces of music that exists. Everything about it is twisted out of shape. She wants to be…to be anyone, or anything, but something unspeakable happened to her once and…it’s not something she’s really ever going to get past. I wouldn’t wish to presume, but the looming wall shadow nightmares of a 16 rpm Johnnie Ray booming about how he’s never going to fall in love again, the slo-mo collapsing towers of trombones – a sense of purposive displacement, verging on derangement, found lately in things like Charli XCX’s “Shake It” (AG Cook helps give hospital nightmares their desired soundtrack) which demands that you figure out exactly why “it’s all over now” – this all points towards a sequel to an unplayable (except once) 1982 Top 40 hit (you go look it up and figure it out). The succeeding cries of “Give me a reason to be…a WOMAN” in “Glory Box” are therefore imbued with deliberate and poignant defiance.

But then again, Bristol…

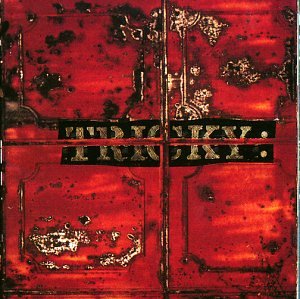

If The Colour Of My Love was top and Dummy second behind it, then Maxinquaye was third (not actually what happened – and acknowledgements and apologies to Good News From The Next World by Simple Minds and Leftism by Leftfield – but it’s the story being told here). Its sleeve photographs inspire efficient thoughts of what “hauntology” might mean (and the Ghost Box people must have picked up on this), and if Beth and Geoff decide this is serious (just as Céline does in “Think Twice”), Tricky and Martina Topley-Bird laugh it all off and drag out several amiably vehement “fuck it”s (what would Maxinquaye be without its fuck wittiness?).

The album, uniformly chosen to the best of its year by everybody in Britain, ahead of more fancied competitors, is like Escalator Over The Hill insofar as it escorts you through Alice’s magic mirror into an entirely new and self-defined world. The spaces of this “Karmacoma” (i.e. “Overcome”) are red and green, compared with the marine blue and white of “Numb.” A thousand neglected television commercials flick through your mind like discarded cigarette ends, and the world’s most hesitant love song commences. Huge booms on disused gas tankers in readiness for another Kuwait, or is that simply the Victoria Light Maintenance Depot?

“Ponderosa”? They’re having a pre-Lily Allen laugh with some old folk tune (weeping willow/wino) or just twisting it into Robert Johnson for replicants (the Devil’s company). It was everything that a 1994 pop record shouldn’t have been and made you laugh and shiver louder, longer and more honestly than most other 1994 pop records. The moment in “Brand New You’re Retro” where Tricky hands over to Martina and the “Bad” backdrop abruptly mutates thrills like fresh oxygen materialising beneath the Kingston Bridge in 1979 Glasgow.

With the icy petrol station synthesiser line descending throughout “Suffocated Love,” I think of an aeroplane, inexplicably coming in from outer space, getting ready to descend and land, and it is 1963 with 101 Strings elegantly scraping their waltz through the speakers; the aisles are full of obediently-dressed stalwart observers of law, the future lies just beyond us, and there are man-made structures so high they almost scrape the sky, built at such an elevated level that some areas of housing and road are permanently snowy, building possibly too high for this planet to tolerate, and descending ever further, into the six o’clock morning, of the pearly promise of modernity moving into our focus. I am possibly alone in thinking this, but then again no one had the same nightmares that I had in hospital three years ago.

“Strugglin’” is fittingly named – the barbed wire, the forced immobility, the trudging through apparent glue, the suffocating pain (the drain, the catheter). “Pumpkin” introduces Alison Goldfrapp as though Billy Mackenzie’s hitherto unacknowledged kid sister had just sashayed sideways into Tie Rack. “I smell of SHE” is not the same as Pacino’s “All train carriages vaguely smell of shit” in Glengarry, but the motive might not be dissimilar – to forget your self, to forget The History Of Music or at least realign it to your purposes (how else do we handle music?).

You know about “Aftermath,” of course – Blade Runner, lullaby to a replicant with no actual mother, only the implanted memories of one, David Cassidy bridged at long last with David Sylvian, elements of Bristol’s recent and at the time retracted path (Maximum Joy, The Pop Group), a song that Vera Hall could have hollered a century ago, the fifties television call signs but you don’t dare move from the top of your distorted stairs to go and change the monochrome set, not that you could move anyway and sorry but you’ll just have to sit there until ten o’clock and WHERE AM I and WHAT IS OTHER and why does everything VAPOURISE and it’s been better written about before as I scarcely need to remind you. You know about “Black Steel,” freed from its concomitant hour of chaos, and who “FTV” really were.

But did you know about 30 January 1995, and the tube train? The only contemporary album mentioned in Geoff Ryman’s 253, which is set on that date, is NOW 30 – both “Protection” and “Glory Box” are featured on it. Because it is all about life, and letting your emotions be witnessed because this might be the best and indeed the only chance you might get. Three different but complementary views on love and womanhood, and a novel, if you can term it that, to turn the square into a hypnagogic parallelogram. The Hammersmith shoppers who descended into any of the three Underground lines which run from there – where did they end up? How did they get on? Did they become happy? Only, perhaps, when, as Céline advises at the end of The Colour Of My Love, indeed at the end of the title song which concludes that album, they accepted the ultimate offer that money could never buy. You sure you want to be with me? I’ve everything to give.