Thursday, 24 September 2015

The CARPENTERS: Only Yesterday: Richard & Karen Carpenter's Greatest Hits

(#406; 7 April 1990, 2 weeks; 28 April 1990, 5 weeks)

Track listing: Yesterday Once More/Superstar/Rainy Days And Mondays/Top Of The World/Ticket To Ride/Goodbye To Love/This Masquerade/Hurting Each Other/Solitaire/We've Only Just Begun/Those Good Old Dreams/I Won't Last A Day Without You/Touch Me When We're Dancing/Jambalaya (On The Bayou)/For All We Know/All You Get From Love Is A Love Song/(They Long To Be) Close To You/Only Yesterday/Calling Occupants Of Interplanetary Craft (The Recognized Anthem Of World Contact Day)

As the new decade finds its feet, no one seems to be sure what to think or where to go. Popular music seems to be a pull between the old and the new, and as you can see, the old has been winning out lately. There was nothing past 1984 on the previous album, and there is nothing past 1981 on this one. It seems as if the 1980s themselves are slowly but surely being erased, that they are too terrible to contemplate, too close. And so nostalgia beckons, and most of the spring - a time of hope and renewal - is marked here by music that is from the past. Why is this?

It is easy enough to say that again - as with Karen Carpenter fan Gloria Estefan - it's the women who bought this en masse, or it was advertised on television, etc. But for seven weeks? That's amazing, but also kind of frightening, mainly for how The Carpenters stand for something that people can still get nostalgic for - a woman in a dress standing and singing a ballad. But Richard and Karen, Yankees transplanted to Southern California at a young age, were not ever that simple.

For one thing, Karen plays the drums and sings;* I don't drum myself, but I can imagine that doing both is tough, but rewarding. (I tend to think of drummers as the ones who really get lost in music, as the beat is so essential that they become the music while it's playing; and drummers are ones who make noise, who can be rebellious, who like a fight.) Richard, on the other hand, is the studio whiz, the arranger, the one who wants to make everything perfect on all accounts, and that kind of Wilsonian mania is great for anecdotes, but not so much for living a normal life. Richard wanted to be a musician when he was 12, and younger sister Karen wanted to drum, only coming to singing later on. Late 60s Los Angeles was their context, a time of jazz/rock and Frank Zappa as much as the complex harmonies of The Association and The Turtles (with the British Invasion/Motown there as the music of their youth, as with all Baby Boomers).

I don't know how much of all this was part of the nostalgia for The Carpenters at this time - very little, I'd guess. Because the painful memory of Karen Carpenter's death lingered on for years with women; the shock of it (though she had been underweight for some time) was intense, even if you didn't particularly care for The Carpenters' music per se.** And so this album, buying it, is a long-delayed act of mourning. 32 is no age for death; anorexia nervosa is no way to go. Maybe the women (and men - I don't want to generalize here too much!) remembered how lively and delicate/tough she was, singing and playing, using her whole body to make music. (This, on the cusp of Riot Grrl, of the decade that saw the rise of so many girls and women making their own noise.)

This is what I would like to think; but of course it could just be this was indeed a direct link to the past, right back (as with the previous album) to 1969, an anchor year for a whole generation. Something ended there, something started there, and once again, the story unfolds...

And of course it begins with "Yesterday Once More" - a song about music from the past and being able to go back. The music industry banks very hard on the public's too-easily-won tendency to, when nothing seems to be happening, go backwards. Radio stations which dwell in the past will always be around, people will always sing along to them. To fix time? To erase the present? To make something old new again? The trick is to do the latter, but the line of least resistance brings the music back as sheer pleasure, almost a kind of drug. Things, people can fade, but the music is still there. (This version, by the way, is the single edit, not the full version with the medley.)

"Superstar" is also about listening to the radio and hearing a certain song, a certain guitar - and the joy here is mixed with pain (Karen's voice suggests both) - this is what happens when you really get involved in music, with a musician. The music is live, the guitarist is real, there is an affair, and then distance. How weak it seems, just hearing the song on the radio as opposed to in person, how tiny the guitarist is, how big the music is. It is a song that goes beyond a crush, and when Karen sings "I really do" at the end, vowing her love to the guitarist, to music itself, it's almost too damn much to bear. Having a song that you share with your Other is one thing, but what if your Other wrote the song? It practically becomes part of your body, I imagine. And it is always there, even if the Other plainly isn't.

"Rainy Days And Mondays" is a lovely song about being in the dumps and not being able to do anything about it. Notice how she's complaining, sure, but it's not like she's Morrissey and has the weight of the world on her shoulders. Karen accepts her sadness (she inhabits her songs; she may not have written them but she makes them her own) and frowns and looks at the calendar - yep, it's to be expected.

"Top Of The World" is a weird song. I mean, it's nice to hear Karen and Richard (he does come in on harmony vocals at times) all happy, but how can anyone actually look "down on Creation"? There's being exalted in love, and there's hovering over the surface of the Earth itself, like you're an astronaut. How powerful a feeling is that? How light, how buoyant, how unreal must the narrator be? The surprise in Karen's voice is real, but the easygoing country feel of the song makes it surreal, brings back the kind of dreamy mellow optimism of the US in the early 70s - all that weirdness is over, the music says. (No wonder The Carpenters were asked to perform at the White House.)

"Ticket To Ride" is quite something - the song is slowed down, both of them sing, and the gorgeousness is almost - almost - decadent. She has been abandoned, sure, but the feeling here is not one of agony, as Lennon wrote it and sang it. That has been replaced by the complete elegance and beauty of the song itself - this is the literal act of hiding inside a song to shield yourself from the meaning of it. It's not so much as a direct homage but an act of love. And it was recorded just four years after the original version, showing what a huge leap there was between the mid and late 60s.

"Goodbye To Love" is a song that seems to come at the end of the universe. Life is mysterious; love is even more mysterious; nothing can be done about either, hence the smile in Karen's hopelessness. Maybe one day things will change? Hm. Maybe. The rocking guitar solo shows her real agony, her real anger, that things have come to such an unpretty pass. The aaaaaaaaaaaaaaahhhhhhhhhhhHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH wall of harmonies at the end does the same - this is the kind of song the generation to come, Generation X, will claim as their own - the complexity here is theirs, right down to the need to take control of love, as if that could be done.

"This Masquerade" is very jazzy, very cool (Karen's earliest influences as a singer were Ella Fitzgerald, Mary Ford and Dusty Springfield) and she sounds right at home here, even though the song is about deception. Are they happy? Not really, but like automatons (is it just me, or is there something kind of unreal about The Carpenters?) they just keep going, unable to find the words, maybe unable to speak altogether. Together alone, lonely together, alienated as hell but unwilling to part. Karen sings it as if it's sad and delicious and slightly sensuous...

"Hurting Each Other" is not a song I had heard before, and I was immediately reminded of Scott Walker (so much of the orchestration here is like his Stretch period, in a way), only to find The Walker Brothers had recorded this! Well of course - it is big and dramatic and foursquare and responsible. They are so good together, why are they suffering like this? It is damn refreshing to hear Karen sing about wanting to stop being miserable, to stop this self-destructive behavior. What with Karen's weight problems and Richard's insomnia and subsequent addictions, well, you know. So many times musicians predict things in their songs, though whether these are self-fulfilling prophecies, I don't know. Irony kind of breaks down with these two.

"Solitaire" is a huge song, one of a man who has deliberately turned his back on everything, on all others, on love itself. (Sigh, so many songs here about being alone, voluntarily mostly, or being in a state that is just as good as being alone, if not worse.) But what's this? He loses his love because he's...indifferent? WHAT?? No wonder Karen sounds, quite frankly, a bit angry here. This is a man who lost his love due to his silence, and she sees him and his little hopes and his bossy ways and how he pretends he'll never love again and scorns his suffering. Oh, she seems to be saying, I feel compassion for you, but not forgiveness. You could love again if you opened yourself up and really felt something, yes it hurts but without that actual grief, nothing is possible.

I mean, look at the couple in "We've Only Just Begun"! They are happy, optimistic, content. The world is theirs, and if there is fragility in the song - melodically, not just in Karen's voice - it's that this won't last. The moments have to be seized, that place where there's room to grow isn't going to appear soon, but if they keep going, it will. This is the smiley face button with a tear in its eye, naive but knowing, fresh and self-aware.

"Those Good Old Dreams" is about love, about fantasies that come true; once again in the beginning she is a child (as she is in "Yesterday Once More") and is a daydreamer. Well, now she is grown up, singing a mild song - happy, but less perky than "Top Of The World." From 1981, and sounds as if it could be 1975, really. You'd never know Karen made a disco record hearing this (one that her label refused to release, and only saw the light of day in 1996). Her voice sounds a bit rough here, deeper somehow....

I'll be getting to their version of "Please Mr. Postman" on Music Sounds Better With Two, but once again here she is being patient, waiting and waiting....

"I Won't Last A Day Without You" is about being in love, but about disappointment too - the world is cold and mean, and her Other is the only thing that can make her smile. It's "nice to know" the Other is there, but how huge is this dependence? "Touch me and I end up singing" she says, as if the Other is actually Music itself. "I can take all the madness the world has to give" she sings, and that is also huge. How could anyone hear this as easy listening?

"Touch Me When We're Dancing" is yacht rock, all swishing strings and romance, stolen kisses and "you've got me up so high I could fly coast to coast." Again, there is a breezy sense of joy here (and the obligatory 80s saxophone solo) and how weird is it to say you want to be "touched" when you are dancing? Unless this is more suggestive than it first seems? And how eerie is it to hear her sing in 1981 about feeling light?

"Jambalaya (On The Bayou)" has always seemed like an odd song for The Carpenters to cover, unless they really liked Hank Williams. Too neat, too sweet (do I hear a flute solo?), it's just...nice.

"For All We Know" is from the movie Lovers And Other Strangers***. It is joyful and sad and "love may grow...for all we know" is the killer lyric here. The two are strangers "in many ways" - but as they get to know each other, they will become closer. Or will they? The music here is ambiguous, but hopeful. (The Carpenters were told to see this movie by their manager while waiting around in Toronto to play as the opening act for Englebert Humperdinck, enjoyed it, and as soon as they got back home recorded the song; it's not in the movie as such.)

"All You Get From Love Is A Love Song" is such a meta title, and once again we are in yacht rock - "love was washed away" and it's a "dirty old shame" that her love is over. "The future lies before me - I cannot see" is the abyss of the song. This seems to be some kind of sequel to "Superstar" as she is the one who broken his heart, and he is going to write a love song about it, because "the best love songs" are written by someone who is broken hearted. Well no wonder she sounds smug! Oh poor songwriter, how do you like things now? Sure, my future is over, she is crying and cannot appreciate the sunrise, but all you, musician, get is a song. That's nothing to be too happy about, compared to being in a relationship is it?

Is it?

"Close To You" is one of those songs that suggests romantic adoration that is kind of crazy, but then lovers can be a bit crazy, and it's Bacharach and David, so it sounds magical, and Karen is soft and the whole thing is like being hugged the whole way through. It's a song with real jazz changes (as easy-going as it sounds) and it was covered with tremendous verve by Errol Garner on his album The Magician in 1974; the pastel teddy bear waaaaaaaaaAAAAAAAAAAAHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHhhh of The Carpenters is replaced by a full-on rainbow of joy.

"Only Yesterday" is about loneliness - "in my own time nobody knew the pain I was going through" stings here, for certain. The morning light she can't see once she's dumped her musician comes back - "maybe things will be all right." The same guitarist from "Goodbye To Love" is here, now that she is happy, at home in his arms..."the best is about to be." And his love is making her feel "as free as a song, singing forever." In all this narrative, has she now found happiness? This song is too tentative for that conclusion, but it's a kind of girl group song, one where hope beats experience yet again, where long-term contentment may be possible, even...

And then there's "Calling Occupants Of Interplanetary Craft" which is Canadian weirdness and a sure sign of something itching inside both Carpenters to go a bit south, if only their public would let them. In the narrative here it's as if she's gone through all this romance only to look to the skies for a greater love, somehow. At the time I didn't quite understand the whole Close Encounters/UFO mania of the late 70s, but here is the hapless LA radio jock and the alien, here is the magnificence of the whole universe, and Karen speaking for the Earth's citizens by saying "we are your friends." (It also led to this weirdness, which I didn't watch but cannot help but imagine.)

And there we are, left looking into space with The Carpenters, who maybe really were the aliens who came down, did their business, and then disappeared, in Karen's case too painfully literally. That the public wanted this more than anything as the new decade began shows how uneasy they were, how frightened - and, I would guess, how profoundly attached to their past (and therefore, youth) they were, as well. Even if the past represents two people giving themselves to music so fully that it seems to have ruined them both for a while, that, that is what the public are happy to buy the most for weeks on end; ignoring their fates, ignoring the implications of the songs, lost in the melodies and the undeniable greatness of some of the songs and nearly all of the singing (Karen's voice does get a bit weaker by the end). But the end result is a denial of the present, a preference for the past over the present, a paralysis that comes when the public cannot get a handle on what is happening; we are now fully in that period when everything is up in the air, and many will reach back for something, anything, rather than squarely deal with what is here, right in front of them....

...which is never a good idea, in the ocean of sound....

Here in London, on Regent Street, not that far from Piccadilly Circus, is a literal ocean. It is in the display window of a clothing store, a big chain, but the display isn't clothing. It's a huge screen showing...the Pacific Ocean. The live feed of shore at Huntington Beach, California. It's a big screen, and it has a blue filter on it so it's all indigoes and shades of white and black, an idealized ocean. It is by far the most beautiful advertising in London, as nothing can outdo nature, and if you're lucky you can see surfers paddling out over the waves and then surfing back, at one with the Pacific itself.

It is one thing to look at this as someone who has never actually seen the Pacific in person and regard it as nice or clever; it is something else altogether to look at it as someone who has seen the Pacific, in person, and remembers it very well. It is like a tonic for me to see it; I claim it, without saying anything to anyone, as mine. It seems silly to claim something so huge, but that is how it feels. Even some of the ocean, filtered and used for advertising, is enough to give me that vital connection, so truly profound that I cannot say anything when I see it, save to remark on it being there and joy at seeing someone there on the screen, paddling out, the memory of salty fresh air and the peace of such a place...

The ocean is the end of things, but the beginning as well; and the Pacific is so big that it extends right down to a place I didn't know much about in 1990 called New Zealand. But once I heard Submarine Bells by The Chills, well....

(Dig the drawing and autograph by Martin Phillips himself!)

It made all kinds of sense to eventually work out that their town, Dunedin, is on the Pacific - sure, it's thousands of miles away, but it's the same ocean, at least. And the music was different from the Australian music I had already heard; I wasn't sure how, though living in a place so close to the Antarctic and so fundamentally away from everything else (Dunedin is on the southeast coast of New Zealand's South Island) I was amazed to eventually read about there being a whole scene down there. I shouldn't have been, though; music often comes from places where there is nothing else to do, save for sport, and the small town (by American standards) of Dunedin fits this perfectly. Martin Phillips started The Chills in 1980 as a teenager, spurred on by the DIY post-punk thing, and after lots of configurations and losses, singles and EPs and European tours...one version of The Chills came to the UK in 1987, toured around, and eventually recorded Submarine Bells.

And thank goodness they did....

Because even if this wasn't a huge album in the US or the UK, I did hear "Heavenly Pop Hit" on CFNY and it had (and has) the same effect on me as that Regent St. advertising. The music is pure Pacific warmth and joy and welcome, that first blessed glimpse of water and sky beyond any buildings; when Phillips sings "OOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOHHHHHHHHHHHOOOOOOO-OOOOOOOOOOOOHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH" in the chorus, I know what he means. The song is about the joy of music itself, but its bigness is due to nature, to the Otago Peninsula, to the freedom being away from it all. Though this was recorded in the UK, Phillips' soul is in Dunedin, is there on that beach, and it is the best Beach Boys-influenced song I've ever heard. Which is to say that though he seems to be from far away, the Pacific unites us; I felt an immediate kinship here that I can't feel with The Carpenters, who seem so closed off from the elements, so perfect; with this song I can too feel floating and happy and FREEEEEE, and after such years as '88-'89 ("we've passed through the dark and eluded the dangers") this was something I needed, and it was new....

....another thing about this song - and the album - was the open sincerity of it; it was not trying to be cool or hip. Phillips is not assuming roles or characters in these songs; they are him, pure expressions of his heart, with no side....

...which is just as well, as the overwhelming feeling here is longing - longing for so many things, and fear as well. This is not a good-time party album, as ecstatic as the first song is....

"Tied Up In Chain" is about neo-Nazis, about prejudice, but mostly about unthinking habit. The "children of gloom" are ignorant and don't care, and "we feel we must be others and this is more than that/if egos are inflated they can crush a people flat"**** - I can well imagine how someone from a place so remote can feel crushed, and have sympathy for those who have been, as well. But the roots of these chains go back through generations, so what seems simple at first to criticize widens and widens...All this over a melody that is nervous but confident, rolling and arching and then resting at the end...

"The Oncoming Day" hurls itself, rocks along, and Phillips rides it like a rollercoaster; he just about keeps up, too. He sings to her, to the glade where they once made love, to the past; he is trying to write a song to say that he still loves and remembers her, but comes up with "nothing worth anything - nothing worth nothing - nothing left in this lump of grey" - how rare this is - "that even vaguely says I love you in a way that pleases me so I'll let the oncoming day say it for me" - this isn't so much New Pop as something else, and we are right there with the day here and the sun rising, and that is enough for him to say, to insist "no one can take your memory away from me!" Nature itself, powerful and cyclical, is the best, the only thing big enough to represent his love, and he cannot be afraid of it, because in a way he is it. The song finishes, but the main question of "Is sustaining past illusion just insanity?" is there. There are fine lines between that and hanging on to the past reality, the pain of it there in the music and words...

"Part Past Part Fiction" is Phillips there in London, feeling alone, "so far from home here" - and now his wordless sounds are of sorrow, loneliness. He hasn't meant to go away for so long, but here he is, knowing things are wrong but unable to do anything about it. (Sigh, the guitar solo. I mean, SIGH and AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAHHHHHHH.) "Where could we dwell in a past alive and well?" he sings, and then the line, the LINE: "You cannot drive and steer rear view." That it takes an expatriate living in London to express such a fundamental truth about life - you can look backwards, but "to hide in fiction and nostalgia can be eerie" is something maybe only us expatriates can really understand. If I feel far away from Toronto here, I can only imagine how lonely Phillips was; at least the Australian contingent of musicians could hang out together, but I sense The Chills were very much on their own....

...and in a 1990 sense, I knew mom and I were going to leave Oakville, we could not stay in a house that contained so many memories, so many things...

"Singing in My Sleep" is a drone that muses on how terrible the world is, and how his singing and music are a protest, a bulwark, against those who hate, those who are blind leading the blind, against "the pressures of musical life." The songs fade when he wakes, but even when he is asleep he is creating music, "songs of such beauty and sadness." These songs are of the Earth itself; once again, there is little division between him and nature...

"I Soar" is a view from high up above Dunedin (I think? it is a steep place) that fills him with great emotion, but he is alone and has no way of expressing himself, outside of describing what he can see, flying with the wind, soaring and seeing that his family have flown away, away from the crumbling homes. The past is gone, his "emotions are imploding" but there's "nothing to say." (So much of Submarine Bells is about communication, about trying and trying to find a way to express things.)

"Dead Web" is superficially jaunty, but is about those who contain their emotions, bury them, pretend they don't exist; they are in a dead web, a world of the past, mourning that that world is gone; Phillips understands this, to a point, but shakes it off, and the song ends sharply, the past best left to those who want to focus on it; he's got enough problems as it is...

"Familiarity Breeds Contempt" is as tough as The Chills get, rocking as Phillips snarls about the perils of coming from a scene so small that backbiting and meanness are everywhere, even within himself; that contempt is as withering and damaging as obsessing over the past, and the song rages against cynicism and hard people, ugly assumptions and "when the past is thought irrelevant our destiny is black" - you cannot go forwards without knowing and appreciating where you've come from, but how stinging was it for Phillips to bear the burden of essentially being The Chills, now a band a decade along with not much success outside of New Zealand? It must have been damn hard to be the band that had to do well in order for the label Flying Nun to do well....and so this is a song that comes out of this constant pressure, as angry as you like....

...and there is the private sorrow of having to be away from the Other, too. It is, to use a word overused these days, devastating. "Don't Be Memory" is a song that flows and halts, falters, and then picks up again, grasping on to something, wanting so much more. "I would tell you love's eternal, but eternity is such a long time" - and the clock is ticking, "we've this greenhouse on"***** - and he wants to forget her, get away from this pain, but he knows he can't. The memories flood back: "Cozy in the north wing, taking turns at Swamp Thing, listening to The Byrds on the tape recorder..." In order to keep his love, he must get back to her, but then OH - "sensing your essence so reminiscent - a forgotten flavour..." and once again I am wordless. He doesn't want her to be just a memory, to feel unrepresented, lonely, because she is there all the time, unbidden, unexpected. And this overtakes his song, that she is there; they will be together soon ("if nothing goes wrong" he worries time and again) but in a way she is there already. "The uncaring power of memory/So crippling in its clarity" - and damn it, there's the whole problem right there, and the only solution, too. The clarity of something means you can see it and understand it, if you have the strength to do so; to get over the "spiteful spikes" of the feelings, to find a place of peace....

"Effluoresce And Deliquesce" is about a couple fighting; but with such poetical words (like the title) that beauty of the song (and it is elegant) can mask the pain, the conflict, but make them like dance, a back-and-forth (the song pauses regularly, as if we are watching the argument like a dance of sorts) that rises to admit the "anger flows like fire" but on such a watery album, it goes, extinguished, and in an hour "they burst into flower." They are slow to ice over, quick to turn into a supernova, but the happy end is always there, and they reach it and the song ends, neatly.

"Sweet Times" is a holler and a strum about how the world, no matter how useless things may seem, still hasn't ended....a holler that times are sweet....

And then comes "Submarine Bells." And suddenly we are in the Pacific again, deep inside the inner ocean******, with a lullaby so beautiful that like the first song it reminds me of the live feed from Huntington Beach, the soothing waves, the ease, the gentleness...the slowness of the song like a descent into the water itself..."I slice the surface here beside you/lungs filled liquid yell I love you/sound moves further underwater..."

I wish I could remember how it was when I first heard this, but the fact that I listened to it more than any other album in 1990 should tell you enough. It was my solace; it was and is one of my favorite albums of all time....

"Deep and dark my submarine bells groan in greens and grey/mine would chime a thousand times to make you feel okay..."

This, this is just one example of what was actually happening in 1990, but was ignored in favor of the past. It is wise, tender, aware, current. It deals with that tug of the past, of sentiment, and ends with something deep and profound and great. Is Dunedin fundamentally so far away? I didn't feel it was in a way, which ended up with my buying a guide book to New Zealand and reading and rereading an article about The Chills and willing myself into that experience, especially once my mom and I did move to Toronto that summer.

There was, of course, another album of this time that counselled against nostalgia, and it couldn't have been more different:

Oh yes.

Flood (that watery theme again!) is so good, it's ridiculous, and the UK public eagerly took to it, because of the hit single, "Birdhouse In Your Soul." If the sheer gorgeousness of Submarine Bells hides the tough messages it has (and in part it does) then Flood's great humor can mask its equally tough messages. "Why is the world in love again? Why are we marching hand in hand? Why are the ocean levels rising up?" ask TMBG in the first song, and the only answer is that "It's a brand new record album for 1990." New decade, y'all, and it's not small in any way...

"Birdhouse In Your Soul" is pure dorky happiness, beeping and trundling along, happy, going forward. Is is a parody of R.E.M.? I don't know, but the "bluebird of friendliness, like guardian angels it's always near" - and it's a tough little bird, this blue canary. Is it a love song? Is it the future singing to us in the present? The word makes it spiritual too, eternal even....

"Lucky Ball & Chain" and "Twisting" are both songs about a woman who has left her guy; the guy is baffled, sad, the woman is free, and the man is left to his own railroad apartment, her old copies of Young Fresh Fellows and db's records back....

The first argument against fixating on the past - it's too late, it's gone! - is their cover of "Istanbul (Not Constantinople)" - "if you have a date she'll be waiting in Instanbul." Why the change? "People just liked it better that way...." The world changes, and you have to change with it...

There are two...well, I hesitate to use the word "perfect" here, but let's just say really really awesome songs and leave it at that, on Flood. "Dead" is the first one, a simple song with a piano, the two Johns and a lament that "I returned a bag of groceries accidentally taken off the shelf before the expiration date" and then "I came back as a bag of groceries accidentally taken off the shelf before the date stamped on myself." It took me a while to figure this out, but "I will never say the word procrastinate again/I'll never see myself in the mirror with my eyes closed" is was straight enough for me at the time. There is no time to waste, to give up before your time is over. Otherwise you may as well be dead. "Was everybody dancing on the casket?" "Now it's over I'm dead and I haven't done anything that I want/Or I'm still alive and there's nothing I want to do...." If Martin Phillips wasn't as drastic as this, this is still his point - that getting caught in a dead web is something to be avoided, at all costs...

"Racist Friend" is about racism, but also about a party, about drinking, about conformity and feeling like a hypocrite "bobbing and pretending" that what is happening is happening. It is about as hard-rockin' as TMBG ever get, with a Latin trumpet solo in the middle perhaps nodding towards the racist's prejudices...."can't shake the Devil's hand and say you're only kidding." The party is over, 80s hypocrites!

"Particle Man" is a song so simple and easy you can close your eyes and see the animated short in your head (as my father would have, had he lived to hear this song). Particle man is Generation X, Universe man is MASSIVE, Person man is hopeless - "who came up with Person man?" - and then there's Triangle man, surely one of the greatest fictional villains, who fights and always wins, who hates for no reason....

And now the other great song - "We Want A Rock." I don't think there is a thing wrong with it; and it is all so casual! "Where was I, I forgot the point that I was making....I said if I was smart that I would save up for a rock to wind a piece of string around." (Is it just me, or does this sound like a Walkman? An iPod?) In short, "throw the crib door wide"....by the time this completely hummable earworm of a song gets to "Everybody wants to wear a prosthetic forehead on their real head" then the complete madness of conformity and doing something just because everyone else is doing it (the two Johns' singing here is utterly straight and with no side, as if this behavior was just as normal as any) could not be more clear. (The prosthetic forehead costs seven dollars, by the way; a rock to wind a string around must cost a lot more...) Accordion! Fiddling! As usual, TMBG makes outsiders, those who don't fit in, feel a bit better about themselves....

"Someone Keeps Moving My Chair" is of course about Mr. Horrible, the ugliness men, the many things they do which annoy him, but he's so so horrible none of these things bother him so much as he can never find his chair. One of the many songs They Might Be Giants have about work...which leads straight into "Hearing Aid" and the about-to-burst anger ("don't say the electric chair's not good enough for a king-lazy-bones like myself") with Arto Lindsay himself on the guitar, scraping and giving the song - otherwise weirdly reggae like - the paranoid messed upness it represents. Is there a reason for this employee to be so angry with "Frosty the supervisor"? No, it's "BECAUSE....BECAUSE!!!!!!"......

...."MINIMUM WAAAAAAAAAAAGE!! HEEEEEEEEEEAAAAAAAAAAAHHHHH!"

(whipcrack) (60s tv theme about the poorly paid)

And now, for a moment, back to love...

"Letterbox" is a crowded song - speeds by with the speed of a sparrow - "and I never know what I never know what you are what you are, oh...."

"Whistling In The Dark" is about the haplessness of being yourself in a world that so often tells you to be yourself, but is that enough? The narrator is "having a wonderful time" (even though he's in jail - due to being himself?) but would rather be whistling in the dark - and the song thumps along like a marching band going down a cul-de-sac, turning and then turning again, finally figuring out there's only one way out....

"Hot Cha" is about missing someone who never really acts normally - maybe he acts like himself? And the details are glorious - "left the bathtub running, stereo on and cooking bacon, never came back to tell us why." A jazz song about someone who just leaves, comes back, leaves again....

"Women And Men" is about nothing more than the ocean of sound as it's reflected in the many people of the world (echoing the beginning of "Heavenly Pop Hit" and the many millions mentioned there). "Three by three as well as four by four" the population on the land grows, and the river of people eventually becomes an ocean with ships bringing more women and men....

"Sapphire Bullets Of Pure Love" is one of those haiku type TMBG songs that are lovely and sweet but I am never sure what they are "about"; it just is, and I will leave you with the mystery....

"They Might Be Giants" is just awesome, though, as a theme song. "Hang on, hang on tight" says the narrator (I don't know who it is) who elaborates later: "so everyone has to hang on tight just to keep from being thrown to the wolves." Who are they? Well, they might be anything, small, big, who knows, but what to do besides hang on tight? "They might be big big fake fake lies - tabloid footprints in your hair." But can we be silent, Generation X? No! Because they might be giants....

The album ends with the sobering "Road Movie To Berlin" - "Can't drive out the way we drove in..." Much later in the 90s I remember listening to Flood on a trip back to Oakville; visiting the graveyard, the old record store, and agreeing with the driver that being "the nicest of the damned" was about all Generation X - or our little social circle - could hope for. "Time won't find the lost" the song says, as if to say, yet again in a different way, that now is now and the past is the past. Berlin isn't what it used to be; the old road back home is the old road, and there is only the past to find there....

Though this was an actual hit album in the UK, I don't know if anyone who bought Flood also bought The Carpenters; I doubt it. As friendly as it starts, it leaves on a note of cinematic doubt and worry; the bluebird of friendliness seems a long way away. But it is a fiercely realistic album, the sort children would understand much faster than adults, all over the place musically but hanging together with great humor, wit, intelligence and fun.

Both The Chills and They Might Be Giants act as a counter to the seemingly endless nostalgia represented by The Carpenters, and I would like to think they were at least heard and understood by some people, but again I also sense a generation gap here, between those who are looking back and those who find it eerie, creepy to look back too much, lest they get stuck there. Those who are wary are in the minority for now, but soon enough will begin themselves to have hit albums, and wrestle with the past in their own way....

...but for now, rest in peace, Karen Carpenter - this is the last time The Carpenters grace Then Play Long, and for better or for worse, we must move forwards....

Next up: more nostalgia?

* A rarity even now, and something to admire her for, really.

**I grew up hearing them in places like the dentist's, the doctor's, friend's houses, and then on my own radio, once I had one. I had no ideas about them, really, besides that she could really sing. I can't get nostalgic about them as I don't associate them with the 70s in any big way. But I know so many female singers who did listen - Jann Arden, the aforementioned Estefan, Chrissie Hynde, Kim Gordon...who wrote an open letter to Karen once that ended, "Did you ever go running along the sand, feeling the ocean rush up between yr legs? Who is Karen Carpenter, really, besides the sad girl with the extraordinarily beautiful, soulful voice?" (Girl In A Band, pg. 173)

***In one of those odd coincidences, there was (and still may be) a nighttime radio show in Toronto called "Lovers And Other Strangers" which plays soppy songs and has the broadcaster telling poignant stories about love. Is Don Jackson still there on CHFI, soothing the romantic pains of the masses?

****The way Phillips pronounces "flat" is very New Zealand, and being an American susceptible to foreign accents, I liked it right away.

***** This is the first time the greenhouse gas problem is mentioned on Then Play Long, and there's lots of info in the album's booklet about this, nuclear bomb testing and other problems of then and now....

******This is no more the "real" ocean than the "Wide Open Road" of The Triffids was an actual road.

Thursday, 17 September 2015

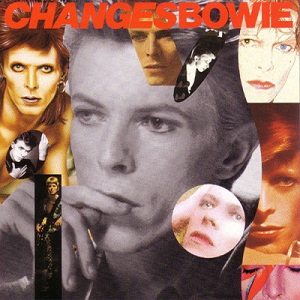

David BOWIE: ChangesBowie

(#405: 31 March 1990, 1 week)

Track listing: Space

Oddity/Starman/John, I’m Only Dancing/Changes/Ziggy Stardust/Suffragette City/The

Jean Genie/Life On Mars?/Diamond Dogs/Rebel Rebel/Young Americans/Fame ‘90/Golden

Years/Sound And Vision/“Heroes”/Ashes To Ashes/Fashion/Let’s Dance/China

Girl/Blue Jean

(Author’s Note: In the fine tradition of the early Now series, you actually get less value if you buy the CD edition; “Starman,”

“Life On Mars?” and “Sound And Vision” appear only on the LP and cassette

editions, and their omission from the CD strikes me as being as ridiculous a

move as releasing a Beatles compilation which left out “Please Please Me,” “Strawberry

Fields Forever” and “I Am The Walrus.” Who on earth would buy that?)

The delay is because Lena was originally going to write this

entry but found dealing with the masses of information available on Bowie stressful to the

point where even the chance hearing of one of his songs induced a headache. So

she has passed it on to me, and I have to say that listening to ChangesBowie is one of the strongest

arguments in favour of paracetamol you’re ever likely to encounter.

As much as some of the number one albums of the nineties

argue strongly in favour of a future, there was an equal and opposite reaction

which heavily promoted the virtues of looking back. For the second time in TPL’s history, a generation was

compelled, or persuaded, to re-examine its own memories, and so there are

plenty of long-term hits compilations coming up, of which this is the first; a

highly selective summary which includes nothing recorded before 1969 or after

1984.

The cover alone indicates that Bowie was as appalling a

custodian of his own work as Apple were of the Beatles, featuring a photograph

identical to that on the cover of 1976’s ChangesOneBowie

but pasted over haphazardly with snippets of other Bowie album covers like a

neglected advertising hoarding. Indeed, as far as the CD edition is concerned,

its first eleven songs are identical to those on ChangesOneBowie, except that the latter included the original and

immeasurably superior version of “Fame.” From 1981’s ChangesTwoBowie, only “Starman” and “Sound And Vision” reappear,

although the “Ashes To Ashes” and “Fashion” on ChangesBowie

are the full album versions, not the single mixes.

The compilation throws up the extremely important question

of whether I have the energy to say anything new about these songs, which on

the CD in particular seem sequenced in a way to make Bowie come across as bland and Radio

2-friendly as possible. This is the “classic” Bowie, the only one most people,

if they are honest with themselves, give a damn about. It is the Ziggy crutch

which leads to situations where Chris O’Leary’s Rebel Rebel, without a doubt the best, most informed and most

trenchant book about Bowie that you will ever read, is not reviewed in

broadsheets or magazines, cannot be found in bookshops, whereas cut-and-paste

books of photographs or “In His Own Words” rush jobs are present in their

abundance. Indeed it would not be hyperbolic to state that Rebel Rebel is vastly superior in intent and delivery to Revolution In The Head – the latter

gives rise to a serious consideration of the worth of “good writing” since the

twenty-one years since its first publication have demonstrated its author to

have been wrong-headed about nearly everything that the Beatles did (and its

preface and postscript now seem, more than ever, like extended cries for help);

however, because it was well-written, it has acquired the status of a Bible.

Nevertheless, ChangesBowie

simply leaves me exhausted. It paints a picture of a chancer who had a hit in

the late sixties about drug addiction which everybody assumed was a moon

landing cash-in and then progressed to boring, sub-Stones cock rock schlock

before getting depressed but good in the second half of the seventies and the

very beginning of the eighties, and emerging out the other side with boring,

sub-Asia adult orientated rock schlock. Even the Aladdin Sane and Diamond Dogs

singles sound shockingly anaemic out of their albums’ context, suggesting that

some remixing had been done.

“Young Americans” is so good because it marks the moment

when Bowie

wakes up with a start from his romantic fifties greasy dreams and wonders aloud

what all this bullshit has been hiding. “Golden Years” in conception, delivery,

performance and production is about as perfect as pop songs get, even

withstanding a Crackerjack assault. “’Heroes’”

is meaningless in its single edit other than setting the stage for big eighties

rock with its Big, Meaningful Statements; Live Aid proved how easily this pop

Frippertronics could turn into standard stadium fare, but Bowie, Eno and Fripp

all approach the full album version

with a mortified exuberance which suggests that this might be the last song

anybody sings (like its nephew, “Being Boring,” it did only modest commercial

business but eventually evolved into one of his big crowd-pleasers on stage).

But the deathly hallow of the last three songs, from Bowie’s cleaned-up, corporate, forget-the-weird-stuff-please eighties, suggests that nothing was learned and most things that mattered were forgotten. Bowie is mainly interesting when whatever mask he is wearing at any given time falls. As a Rich Rock Tapestrian in the line of Rod, Elton and Sting, he might as well be a Hallmark Collectible Ornaments advertisement. The nadir of this album is the "Gass mix" (somebody called John Gass, under Bowie's supervision) of "Fame" which systematically strips out most of what was interesting, attractive and wrongfooting about the original, including most of the Lennon input. Did Bowie really feel a burning need to remind those Jesus Jones who was scratch n' mix boss?

Next: Some heavenly pop hits, if anybody wants them.

But the deathly hallow of the last three songs, from Bowie’s cleaned-up, corporate, forget-the-weird-stuff-please eighties, suggests that nothing was learned and most things that mattered were forgotten. Bowie is mainly interesting when whatever mask he is wearing at any given time falls. As a Rich Rock Tapestrian in the line of Rod, Elton and Sting, he might as well be a Hallmark Collectible Ornaments advertisement. The nadir of this album is the "Gass mix" (somebody called John Gass, under Bowie's supervision) of "Fame" which systematically strips out most of what was interesting, attractive and wrongfooting about the original, including most of the Lennon input. Did Bowie really feel a burning need to remind those Jesus Jones who was scratch n' mix boss?

Next: Some heavenly pop hits, if anybody wants them.

Thursday, 10 September 2015

Sinéad O’CONNOR: I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got

(#404: 24 March 1990, 1 week)

Track listing: Feel

So Different/I Am Stretched On Your Grave/Three Babies/The Emperor’s New

Clothes/Black Boys On Mopeds/Nothing Compares 2 U/Jump In The River/You Cause

As Much Sorrow/The Last Day Of Our Acquaintance/I Do Not Want What I Haven’t

Got

To illustrate how rapid and drastic the change was, here is

a list of Britain’s

number one singles for the first half of 1990:

13 January: New Kids On The Block – Hangin’ Tough (2 weeks)

27 January: Kylie Minogue – Tears On My Pillow (1 week)

3 February: Sinéad O’Connor – Nothing Compares 2 U (4 weeks)

3 March: Beats International ft Lindy Layton – Dub Be Good

To Me (4 weeks)

31 March: Snap! – The Power (2 weeks)

14 April: Madonna – Vogue (4 weeks)

12 May: Adamski ft Seal – Killer (4 weeks)

9 June: England/New Order – World In Motion (2 weeks)

23 June: Elton John – Sacrifice/Healing Hands (5 weeks)

That remains a remarkable list. Some of these songs have yet

to be discussed in Then Play Long, at

least two of which will be in altered or re-recorded form, and there is a

pleasing symmetry to the list, as Sinéad O’Connor covered “Sacrifice” rather

brilliantly for the 1991 Elton/Taupin tribute album Two Rooms.

It couldn’t, of course, last. The backlash took hold

immediately thereafter, and the rest of the year’s number ones included

reissues from the seventies and sixties, a movie power ballad which its singer

(and, at her insistence, co-writer) has essentially disowned, a somnolent Christmas

song and three of the worst number ones of all time. There is only one new

record – which we will discuss later in this tale – which I would not wish to

consign to the skip.

But the changeover from Kylie – an actress acting the role

of a pop singer – to Sinéad – a woman who has no choice but to sing – is the

key moment here. Listening to this album, however, provokes amazement in me

that it did actually get to number one – amazement in a good way, since this is

perhaps the first rock record by a woman since Horses to state its case so firmly yet also so compassionately –

and I wonder whether the seven million people who bought it, presumably

expecting an album full of “Nothing Compares 2 U”s, were really prepared for

its confessionals. Perhaps they looked at the cover, which cannot help but act

as a comment on, or antidote to, …But Seriously (lyrics handwritten in black ink on a white background, the exact

reverse of Collins’ approach), and not unreasonably thought that this was where

the nineties started.

But “Nothing Compares 2 U” has to be dealt with first. Here

is how I propose to deal with it.

My favourite Tintin book, in common with many readers, is Tintin In Tibet; certainly it was the

most heartfelt of all Hergé's volumes. His friend Chang is flying to Europe to

meet him, but he hears that there has been a terrible 'plane crash in the Himalayas, with all crew and passengers presumed killed.

He is inconsolable yet still resolute. He attempts to come to terms with his

grievous loss - he acts as though his right arm has been severed - but finds

that the only way he can do so is, firstly, through dreams, wherein he sees

Chang lying in the wreckage, injured but alive, crying for help, and secondly,

through action, as he prepares to travel to the mountains to find him.

Everybody thinks he is mad or deluded or as blinded by grief

as the Himalayan snowstorms would blind the unwary traveller. But he will not

be dissuaded from his task - despite the overpowering sense of loss he has

refused to accept death and will make every conceivable effort, and many

inconceivable ones, to find that there is still life at the other end, despite

all appearances.

Captain Haddock goes with him, grumpily complaining as ever

- but still he goes with him, will not let him travel alone despite Tintin's

howls that he will travel alone if necessary. The journey is hazardous and

sometimes hopeless; even their sherpa and his crew eventually abandon them,

afraid of the mythical yeti. This dread of the unseen "monster" -

really a fear of the unknown, or of the future - gradually deepens throughout

the story.

Eventually the yeti, huge and loud, emerges from behind a

rock. It is an awesome and startling sight, but Tintin is keen enough to

discern its true nature and knows that it too is afraid. He follows the yeti

back to its cave - and there within the cave, wrapped in warm blankets with

remnants of the small animals the yeti has brought back to keep him fed, is

Chang, extremely weak but alive.

I don't think I need to underline at least one of the many

analogies of this story. But Sinéad O'Connor has always struck me as a similar

spirit; sometimes beaten, often abused and jeered at, but she continues to defy

the onset of death, betrayal and loss even as she stares them in the face, as

if to stare them down. She is noticeably less politic and far more prone to

open bleeding than the fictional Belgian - but which other singers, male or

female, were producing work in the order of The

Lion And The Cobra in 1987/8, with its panting haemorrhages of passion

thwarted ("Troy") or ravenously desired ("I Want Your (Hands On

Me)"), its torrents of naked rage ("Jackie"), its rejection of

nothingness ("Never Grow Old")? This was the flipside of Enya - everything

enclosed in the Watermark world floods

out into Sinéad's soul and onto the red page.

Ridiculed, threatened and boycotted for nothing more than

believing things, expressing these beliefs and standing up for herself and

those for whom she cares - for daring to be an Uppity Woman, even in the

supposedly utopian and caring nineties - she shrugs some things off, screams

away others. Her reading of Marley's "War" at the Dylan tribute gig

was closer to the bruised heart of Dylan than any of the other politesse

offered up that evening - and Neil Young, for one, knew it (as, presumably, did

the author of "The Lonesome Death Of Hattie Carroll" himself). On

1994's Universal Mother she includes

home recordings of her infant son, a decade and more ahead of Aerial. Her 1992 covers album Am I Not Your Girl? - as with its bloody

Celtic twin from the other end of the decade, Kevin Rowland's My Beauty - uses the songs of her life

to tell her apparently unpalatable story; the breaking down on the acappella

"Scarlet Ribbons," the Centipede-style free jazz eruption which

climaxes "Success Has Made A Failure Of Our Home" - an outrageous and

brilliant addition to that year's Top 20 singles chart, and it should have been

number one for 16 weeks - the reading of "Don't Cry For Me Argentina"

she remembered from her schooldays; it all makes her sense.

Because if you're going to attempt somebody else's song, and

carry it off successfully, you have to insert yourself into it; you have to

give the song something which only you could give to it, a route into its heart

which no one else could hope to negotiate. So "Nothing Compares 2 U,"

a song Prince gave away to The Family, one of his shortlived Paisley Park

Nearly-Hit Factory sidelines, in 1985, becomes in Sinéad's eyes, mouth and

heart a different song entirely.

And Sinéad's "Nothing Compares 2 U," as it

struggles with its nearly inexpressible emptiness, also becomes the first real

number one of the nineties, a Massive Attack production in all but name. Nellee

Hooper's production and Nick Ingman's arrangement are more minimal than anyone

else dared get away with at the time, yet the record's depth is maximalist to

its core; a simple but dense string line which does nothing much apart from

stating the underlying basic chords of the song, with no embellishments or

flourishes apart from a slow rise of the first violins in the instrumental

break, drifting like admonitory clouds over Sinéad's grieving figure; a sparse

piano; distant backing vocals like a Gregorian chain gang; and a 16 rpm hip hop

beat with subtle embellishment from John Reynolds' live drums. Just as The Lion And The Cobra, through the

involvement of Marco Pirroni and Kevin Mooney, helped mutate Antmusic into

unexpected shapes, there is something of an umbilical link between Sinéad's

"Nothing" and the Associates' "White Car In Germany" - the

beats too deep and slow to seem real (is Paul Morley's Nothing the missing link between the two?).

The arrangement has to be minimal because Sinéad has to be

in the foreground. Her vocal, though automatically double-tracked, is

unobtrusive but unavoidable. Avoiding undue melismatics, but forceful when she

needs to be ("GUESS WHAT HE TOLD ME?"), Sinéad's vocal asks nothing

more than you listen and empathise.

And she grieves; the minutiae of ghastly bereavement

("It's been seven hours and fifteen days"), the initiation of wilful

self-destruction ("I go out every night and sleep all day"), the

forced gasp of suppressed liberation ("Since you've been gone I can do

whatever I want"), but knowing throughout that all these transitory

pleasures, or drugs ("I can eat my dinner in my fancy restaurant,"

"I could put my arms around every boy I see"), cannot begin to fill

the unthinkable void, and neither can well-meaning but bland advice ("He

said girl you better try to have fun no matter what you do...but he's a

fool").

But for whom is she grieving?

The line "all the flowers that you planted, mama"

is the song's true core of grief. Note that:

a) she doesn't change the gender;

b) she whimpers the word "mama" like an infant;

c) this is the precise point on the video when her tears

become visible (the similarly minimalist video, the face and nothing but the

face on a background of unfathomable blackness).

And this was where she started to think about her own

mother, the mother who abused her beyond any rational endurance, and yet when

her car crashed it was still like having an arm amputated without anaesthetic.

"I know that living with you baby was sometimes hard/But I'm willing to

give it another try" - is she putting words in her mother's mouth,

paraphrasing her afterlife regret and hoped-for penance?

But she, Sinéad, is still willing to give life another try, declines to die, will

not be dissuaded no matter how much shit is rained down upon her head or jammed

into her heart; and so her "Nothing Compares 2 U" cut through all the

jive bunnies, jovial teenpop cutouts and bogus AoR compassion which had

preceded and still encircled it - its appearance at number one was a defiant

and shocking bolt of thunder thrown into an arena of bland acceptance of

business-as-usual, since business, the WORLD, just STOPS when you've lost

someone, I mean, how DARE it CONTINUE...there is something about the record

which gets as close as pop has ever dared to "the truth"...and no, if

you know what that is, it doesn't require definition. Think of Sinéad

struggling through the snow and cold, sometimes seemingly on the point of

death, but refusing to stop until she finds the candle of life which she knows

is glowing at the other side, at the entrance, after confronting apparent

demons which are only bigger guides...back to life, however we do want it.

The rest of the album circles around these concerns. “Feel

So Different,” set against a string chart which reminds you that if the Beatles

had actually played “Eleanor Rigby”

as a group it most likely would have been angry punk rock, begins with

Niebuhr’s Serenity Prayer, a passage most commonly used by entrants to

Alcoholics Anonymous, before becoming an extended prayer of awe (and

conversion, or re-conversion?) to God.

“The concept of ‘the value

and dignity of the individual’ of which our modern culture has made so much is

finally meaningful only in a religious dimension. It is constantly threatened

by the same culture which wants to guarantee it. It is threatened whenever it is assumed that

individual desires, hopes and ideals can be fitted with frictionless harmony

into the collective purposes of man. The individual is not discrete. He cannot

find his fulfilment outside of the community; but he also cannot find fulfilment

completely within society. In so far as he finds fulfilment within society he

must abate his individual ambitions. He must 'die to self' if he would truly

live. In so far as he finds fulfilment beyond every historical community he

lives his life in painful tension with even the best community, sometimes

achieving standards of conduct which defy the standards of the community with a

resolute ‘we must obey God rather than man.’”

“I Am Stretched On Your Grave” is Frank O’Connor and Philip

King’s free variation on the anonymous seventeenth-century Irish poem “Táim

sínte ar do thuama” set against the same “Funky Drummer” sample used on

Fresh 4's “Wishing On A Star” with only Steve Wickham’s fiddle as accompaniment to the

singer’s maternal mourning; while it is not surprising that this was soon

remixed by Hank Shocklee and that Sinéad should align herself with hip hop, it

again begs the question – as does the far more acute and hurting “You Cause As

Much Sorrow” – of how a bereaved person is supposed to act, what they are

supposed to do, the memory from which they struggle to free themselves.

“We take, and must

continue to take, morally hazardous actions to preserve our civilisation. We

must exercise our power. But we ought neither to believe that a nation is

capable of perfect disinterestedness in its exercise, nor become complacent

about a particular degree of interest and passion which corrupt the justice by

which the exercise of power is legitimatised.”

The state of the world is in large part subsidiary to the singer’s

own emotional crises. Hence the mother of “Three Babies” turns up again, in the

third person, two songs later, on “Black Boys On Moped,” another song whose

lyric has unfortunately failed to date (“These are dangerous days/To say what

you feel is to dig your own grave”), her main concern is getting her son out of

Thatcher’s Britain so that he doesn’t have to witness this pain, or even know

that it exists, and the role of the family again rises to the fore in the rear

sleeve photograph of the parents of Colin Roach – to whose family the album is

dedicated. His parents stand, mournful and silently angry, in the rain beside a

photograph of their son; the picture is captioned “God's place is the world;

but the world is not God's place.”

“Our dreams of bringing

the whole of human history under the control of the human will are ironically

refuted by the fact that no group of idealists can easily move the pattern of

history toward the desired goal of peace and justice. The recalcitrant forces

in the historical drama have a power and persistence beyond our reckoning.”

As far as her personal life is concerned, it is fair to say

that nobody really knows or understands how she feels. The fairweather friends

whom she mentions in the course of “Feel So Different” re-emerge in “The

Emperor’s New Clothes” but so do relationship difficulties; these escalate

(“Jump In The River”) and culminate in the largely blank “The Last Day Of Our

Acquaintance,” a divorce song of which Tammy Wynette would have been proud –

“largely” because when the song seems to have run its course, Jah Wobble’s bass

and Reynolds’ drums thunder into view and Sinéad’s voice threatens to become a

scream (her performance throughout the record is uncanny, often switching from

damnation to sweetness (and back) in the space of one line.

“Our dreams of a pure

virtue are dissolved in a situation in which it is possible to exercise the

virtue of responsibility toward a community of nations only by courting the

prospective guilt of the atomic bomb.”

But at last we are left with her voice, and her voice alone;

she is the wayfaring stranger, knowing only that she has to escape, get as far

away from her life as she can. She is not daunted by the thought of walking

through the desert – as long as she keeps near the sea. It is all metaphorical,

as the song’s navy blue bird makes clear, but unlike Lorca’s hapless, dying

horseman struggling to reach Cordoba,

there isn’t really any doubt that eventually she’ll make it. The title song is

folk as Anne Briggs would know it – the purity of the voice (although the bird

warns her not to become too pure),

the singularity of her intent, even (as Lena

suggested) something of Lorca’s duende (perhaps both metaphysically and

mythologically). Galaxies away from the First World teen problems of Kylie, and

recorded at the same age as Van Morrison when he made Astral Weeks – as Bangs would have said, there is a lifetime behind this record (later in

1990 Morrison himself sings, or drawls, when asked about enlightenment, “I

don’t know what it is – it’s up to you”) – I

Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got remains startling, sublime and unmatched.

“Nothing worth doing

is completed in our lifetime; therefore, we are saved by hope. Nothing true or

beautiful or good makes complete sense in any immediate context of history;

therefore, we are saved by faith. Nothing we do, however virtuous, can be

accomplished alone; therefore, we are saved by love. No virtuous act is quite

as virtuous from the standpoint of our friend or foe as from our own; therefore,

we are saved by the final form of love, which is forgiveness.”

(All italicised quotes are taken from The Irony of American History by Reinhold Niebuhr, first published

in 1952)

Next: nothing has changed.

Wednesday, 9 September 2015

The CHRISTIANS: Colour

(#403: 27 January

1990, 1 week)

Track listing: Man

Don’t Cry/I Found Out/Greenbank Drive/All Talk/Words/Community Of Spirit/There

You Go Again/One More Baby In Black/In My Hour Of Need

It takes its time to make its point, but the first number

one album of the nineties finally tells us in no uncertain terms that things

are not going to be as they were in the eighties. Initially one listens to “Man

Don’t Cry,” which could be about a soldier’s wife but which I interpret as

being about Mandela, and it sounds like a pleasing enough hangover from the

previous decade; still these songs and the protests accumulated and one has to

remember that this album made number one about a fortnight before Mandela’s

release. Hard as it is to imagine now, the beginning of the nineties, so soon

after the fall of the Berlin Wall, appeared to be one of those rare moments

when humanity got waylaid by an epidemic of common sense.

Still, one notes the presence on this record of sundry

eighties TPL reliables – Palladino,

Katché,

Ditcham – and wonders whether this is going to be anything more than residual

reasonable eighties pop. Given how long it took the first Christians album to

sink in, however, it is hardly surprising that the listener has to work with

the second one, become accustomed to it before he or she gets wrongfooted.

Hence “I Found Out,” which begins with the uncompromising line “I know that the

earth is rotten” (the adjective “rotten” pops up several times throughout Colour, as though an ember of punk

remembrance still burned), suggests a slowly unravelling but gigantic picture

of redemption. The voices become a little too insistent, a touch too

uncomfortable, for plain yea-saying, and the rhythms and arrangement turn

steadily more forceful and less avoidable.

A lot of this has to do with the lead voice of Garry

Christian, which provides some of the clearest and most precise diction I have

heard from a British pop singer since Al Bowlly; frequently he sounds like a

voice from the thirties and forties transported into the ruins of the present.

And there is a very telling arch in his lower register – part Larry Graham, part

Elmer Gantry of Stretch, part foreseeing Ashley Slater’s work with Norman Cook –

as if he is crouching down to you for an intimate chat. This is in large part

why a straight love song like “Greenbank Drive” works; that as well as the

knowledge that really the song isn’t that straight, that the singer’s sense of

lightness of air and rebirth can be said to stand for a greater liberation that

has been gained.

Certainly the anti-politician/tycoon slow burn of “All

Talk” is far less ambiguous and far more forthright in its message and attack

than some other big acts of the period I could mention; this is certainly not a

song of the South, could not even have come from Manchester, could only have

emanated from Liverpool. How can you do a song called “One More Baby In Black” –

a hypnotic and powerful song which starts out as an “In The Ghetto”-type

examination of youth drug addiction and ends up as a militant call to revolution

– with its title’s none-too-subtle Beatles reference and not come from

Liverpool?

However, we are constantly reminded that the Christians

are a vocal harmony group, and a family group at that, whose history stretches

back to before punk; consider the multiple call-and-response routines on “Community

Of Spirit,” a virulently bitter condemnation of neoliberal Conservatism which

ends on the chilling couplet: “I sit here and watch you bleed to death/For what

you’ve done to me and mine.” Sadly, in the twenty-five years after this

recording, it still sounds painfully contemporary. Note also that near the end

of this song, the beats temporarily fold back on themselves – this is one of

the vital aural rhetorical tricks of producer Laurie Latham. Given the presence

of Pino Palladino, and the sleeve’s acknowledgement to “the Kewleys,” it is not

unreasonable to think of Colour as a

cold rationalist remix of No Parlez.

Even the break-up song “There You Go Again” provokes me to question whether it

really is about a serially cheating lover or whether it’s actually addressed to

Thatcher (“It doesn’t matter what you say/I’ve taken all I can”).

Finally a salvation of sorts is found in the closing “In

My Hour Of Need,” a hymn to her, a prayer in praise of light amidst the

remorseless shovelling of topsoil darkness (with some psychedelic backwards guitar

and ambient gambits at its end to remind us that escape isn’t always easy). But

it does seem to me that the album’s centrepiece – it is literally right in the

middle of the record – is “Words,” the best thing The Christians ever recorded.

Such an elegantly patient and wracked performance – Garry’s

vocal takes a long time to come in, as though awaiting his final judgement. In

it he sings, controlled but palpably in pain, about the damage done and how he’s

sorry and how he loves her, but how, how can he possibly describe this in

words? One obvious comparison point is Dexy’s’ “This Is What She’s Like,” but

its roots go much deeper, back to eighteenth-century Ireland, when Peadar Ó

Doirnín composed the poem “Mná na hÉireann” (“Women Of Ireland”). The poem

personifies Ireland as a woman, constantly at the beck and call of her English

master, and crossly wonders why other Irish people don’t defend her. This was

set to music earlier in the twentieth century by Seán Ó Riada, a noted Irish

composer and authority on traditional Irish music who in the sixties

collaborated regularly with the group which would eventually become The

Chieftains. They recorded an instrumental setting of Ó Riada’s adaptation in

1973 which Kubrick used for the film Barry

Lyndon. Subsequently covered by many performers, ranging from Mike Oldfield

to Kate Bush, “Words” is a free adaptation of Ó Riada’s melody with new lyrics

by Henry Priestman.

You could view it as a simple song of love, penance and

inadequacy, but Garry’s performance is too intense for it to be merely that. It

is if he is singing it in the persona of Britain, apologising to Ireland and

trying to make or find peace. For make no mistake, beneath its bright and

opulent-sounding surface, Colour is an

extremely angry record which essentially demands sweeping change. It’s hard to

listen to it in retrospect and not think that the poll tax riots are only about

two months away, that dominoes will continue to tumble throughout 1990. It is

probably more apt to think of it as a Liverpool Steeltown rather than the North West’s riposte to The Road To Hell. Things in this coming

decade are not going to be particularly easy or comfortable.

Next: a woman who would deafen Baile an Mhaoir and the

plain of Tyrone.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)