(#373: 15 October

1988, 1 week)

Track listing:

Sailing Away/Carry Me (Like A Fire In Your Heart)/Tender Hands/A Night On The

River/Leather On My Shoes/Suddenly Love/The Simple Truth (A Child Is

Born)/Missing You/I’m Not Scared Anymore/Don’t Look Back/Just A Word Away/The

Risen Lord/The Last Time I Cried

(Author’s Note: “The Simple Truth” only

appears on the CD edition of this album, but is so central to the record’s

emotional story that it would be remiss of me to omit it.)

To be considered in conjunction with:

MY BLOODY VALENTINE: Isn’t Anything

Track listing:

Soft As Snow (But Warm Inside)/Lose My Breath/Cupid Come/(When You Wake) You’re

Still In A Dream/No More Sorry/All I Need/Feed Me With Your Kiss/Sueisfine/Several

Girls Galore/You Never Should/Nothing Much To Lose/I Can See It (But I Can’t

Feel It)

A story here of two Irishmen, neither of whom was born in

Ireland and both of whom travelled somewhat before settling in Ireland, not

that far away from each other. Chris de Burgh was born in Argentina and spent time

in Malta, Nigeria and Zaire before coming to County Wexford; Kevin Shields was

born in Queens, New York, and grew up there and subsequently in Long Island

before his family moved to Dublin. Both men’s early interests in music were

sparked by close encounters with future musicians of note; de Burgh was keen on

joining The Perfumed Gardeners, a group run by his peers at Marlborough

College, only to be turned down by the group’s leader, one Nick Drake, for being

either “too poppy” or “too pushy” (sources vary). Meanwhile, in late seventies

Dublin, Shields and his schoolmate Colm Ó Cíosóig put together a punk band

called The Complex. On bass they recruited another schoolmate, Liam Ó Maonlaí,

but the group split when Ó Maonlaí left to form Hothouse Flowers.

From there we can proceed straight to the two records

under consideration here, as this is not an encyclopaedia of rock. Flying Colours came out at the beginning

of Ocfober 1988 and is the only Chris de Burgh album to reach number one in

Britain; Isn’t Anything appeared

seven weeks later, in mid-November, and did not trouble the charts at all until

it was reissued in 2012. One received fulsome critical praise; the other was

barely mentioned in despatches. But one earned its right to be in this story,

and the other only by invitation. The one and the other in these two instances

are not the same records.

Yet I believe they are linked. How so? Not just because

of the nationalities of the musicians involved (although the two female members

of MBV are English) but also because they also represent two extremities of how

we view and treat love and our relationships with each other and with the

world. One might invoke the old parable of the classicist versus the romanticist, except that there is clearly a lot about

Chris de Burgh that is unashamedly romantic, and it is difficult to go through

any of Isn’t Anything’s thirteen

songs (both albums have an identical number of tracks) without being aware of

their “classic” precedents. Or perhaps it’s simply the case that each record is

performed at a similarly high level of emotional intensity from two highly

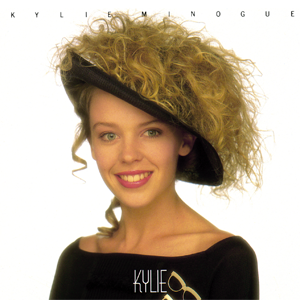

divergent angles. Romas Foord’s cover art for Flying Colours suggests somebody taking off from the planet

altogether, at a distance, while Joe Dilworth’s treated photos for Isn’t Anything has the group painfully

close up, yet smudged and blurred, as if you might only be imagining that you’re

looking at it, at them.

Flying Colours

strikes me as the work of a deeply worried man.

It is true that at the time de Burgh was only just turning forty (as

opposed to Shields’ twenty-five). By now he was the father of two children, his

daughter Rosanna and his first son Hubie, as is made evident by the lullaby “Just

A Word Away.” So it was probably natural for him to be worried; in addition,

given his Irishness, it is important to remember that in 1988 the Troubles were

never far away (in the song “A Simple Truth” he sings about “a country torn

from the south to the north”), and the spectres of soldiers and war are

summoned here twice – and, by implication, also in the quietly defiant song “I’m

Not Scared Anymore,” where he is lying in bed with his wife, thinking of their

children, and for one rare moment his voice rears up into a roar: “Well I know

I’ll protect them with the power of my love/TO THE VERY LAST DROP OF MY BLOOD!”

So much of Flying

Colours concerns itself with protecting himself, and his family, from the

world of shadows and night. On his own he is not to be trusted; wandering some

foreign city in “Sailing Away” he struggles against temptation (“Underneath the

red lights, I am watching where the shadows fall”) and only overcomes it with

some difficulty (whereas “Don’t Look Back,” the nearest this record gets to

uptempo, is a warning against those lights and “red and black” which the

narrator, it is implied, fails to resist, with the song’s dying refrain of “I

should have known better”). In the record’s most comical moment, “A Night On

The River,” he has an argument while nightswimming with his lover, who promptly

takes off with both the car and his clothes.

But the record cuts deeper than that. “Tender Hands,” “Suddenly

Love” and “Missing You” are love songs from different but parallel angles – the

first describes his pained loneliness, the third sees the narrator and his

lover reuniting after a long time apart but its music-and-wine scenario is darkened

by hints of paranoia (“You see, if I think you are beautiful/Someone else is

going to feel it too”). The second, meanwhile, sees him surrendering to a

sensual bliss as complete and enveloping as that described in “Soft As Snow

(But Warm Inside)” with a sustained synthesiser dying of the light at the end

which put me in mind of American Music Club’s “Last Harbor.”

Elsewhere, “Carry Me” is a moving and obviously heartfelt

song about bereavement (“for Mark and Lynda, with love” reads the dedication).

The narrator of “Leather On My Shoes” leaves his home, which has nothing

concrete to offer him, to travel down an unspecified “freedom road,” possibly

the same road the battered, exhausted, hallucinating protagonist of “The Risen

Lord” is wandering however many decades later. “The Simple Truth” is the record’s

centrepiece, a protest against the Troubles and the wider world running itself

down to ruin (“The life of a child is more than a border/The life of a child is

more than religion”) and all other twelve songs lead towards or away from it.

The closing “The Last Time I Cried” returns to the soldiers/war scenario, and

possibly more than that – what the first two verses are implying is pretty

frightening – and seeing both the faces of his child and himself in the picture

of a soldier, he breaks down: “Eli Eli Lama, Oh Lord, you have forsaken me” –

the same words in Hebrew and English. This is not reassuring music.

Certainly, I’m bound to say, it does not reassure me.

There is little doubt, listening to the record, that Chris de Burgh is

essentially a decent and honourable man, if sometimes a rather silly one. Like

Jon Bon Jovi, he knows precisely what his demographic is and how to package his

music to reach them – and that’s a rare thing to find in a musician. I would

say babyboomers approaching middle age, conservative with a small “c,” perhaps

slightly disappointed by both the world and the paths they have elected to take

through it, with dimming memories of how things used to be; such people in the

eighties would have understood Flying

Colours instantly, and these are the people whom de Burgh is trying, with

great skill and artfulness – the album sounds spotless and precise, recorded as

it was in Zurich with co-producer Paul Hardiman, who once produced Lloyd Cole

and The The - to touch and perhaps move.

But I’m just not moved by it. I was certainly never a

target listener, and so while I can appreciate what de Burgh is doing, I have

to admit that it does not touch me or change the way I walk through the world.

Naturally that is down to me and the way I am, rather than any failings on de

Burgh’s part, and I hope that this tentative appraisal is of more use than the “oh,

Chris de Burgh, hyuk hyuk what a lot of crap” crap that emanates from some

unintentionally hilarious commentators; it has always been the purpose of this

tale, not to sneer at records, but to find out why they were so popular and

what they had to say to evidently so many people.

As I say, however, there is this other Irish record from the autumn of 1988 to consider.

“I'm telling you you're a sick mind

You come back so fine, so fine”

(“(When You Wake) You’re Still In A Dream”)

There are other ways of going down the railroad tracks

and never coming back. More bad prose

has been written about My Bloody Valentine than any other musical artist and I

do not propose to add to that pile (indeed, in respect of the interviews which

I sourced for this piece, I do not intend to name or shame the journalists who

wrote such poor copy – always you have to refer to what MBV themselves say to

get to the heart of things). Conversely, no major musical artist is more talked

about and less heard than My Bloody Valentine. You will scan the digital likes

of 6Music and xfm largely in vain for their music. It does seem that radio,

much like the public, has great difficulty acclimatising itself to MBV’s work;

there is the residual feeling that even now, more than a quarter of a century

on from when this music was conceived and recorded, MBV is a little too

disturbing for placid middle-aged radio listeners, represent a bridge that no

demographic dares cross. Yes, I got

MBV when they happened, and so did all the people I cared and care about...but

most, if not actively running away from their music, are passively unaware of

it.

How Isn’t Anything

works is really very simple. If its

music represents rock stripped of most things that make it “rock” – except,

crucially, for the sex – then the record recollects memories of rock as being the

only way to push rock forward. This Kevin Shields did by essentially removing

all “guitar” from the mix; what you hear is the “reverse reverb” effects unit (the

Alesis MIDIverb 1, to be specific, which was bought for the band in error; the

unit had no “reverse reverb” facility as such, but Shields was so impressed by

the sounds he got out of it that he kept it). In other words you are listening

to the “ghost” of a guitar throughout.

Always while listening to Isn’t Anything – largely because of Colm Ó Cíosóig’s aggressive,

rhetorical (“Nothing Much To Lose”) and

exceptionally physical drumming – the listener is aware of illustrious sixties

(and contemporaneous eighties) influences. But the music of MBV was really

unprecedented in rock; the Creation had never done anything like this, and

neither had even Sonic Youth. So the songs here are attack without any

attacking - “Several Girls Galore” and “Cupid

Come” frankly leave the Mary Chain standing (or sidewalking, albeit entertainingly)

– or embrace the listener with a fetid but oddly pellucid closeness that

resembles an indistinct but quietly determined whisper in one’s ear.

At its best, as in the single “Feed Me With Your Kiss”,

voices and instruments lunge towards the listener from entirely unexpected

perspectives, like Sonny and Cher being Doppler tested. The group seem intent

on pummelling this desire into the ground – how many beats or breaks does the

song need? Not even Hüsker Dü had gone that far. It is as if the

kiss is so powerful it will violently dismantle the DNA of the love song for

good.

I think the essential difference between this record and Flying Colours is that they stand on

opposite sides of the same line in the sand. Flying Colours will never cross that threshold because it sees no

need to do so; everything the artist wants to express is expressed plainly and

without ceremony. But Isn’t Anything

sounds as though it has made the quantum leap to the other side; looking desire

and dirt directly in their faces and learning to live with them, allowing their

implications to alter the molecular structure of what this music represents. Isn’t Anything comes down on the side of

adventure, of risk, facing down the fear of failure.

Those who know and love the record will have their own

memories of the time it appeared and how they reacted to it, and – for now – I’m

going to keep mine to myself. I will say, however, that my favourite moments of

Isn’t Anything are the slower ones;

the closing “I Can See It (But I Can’t Feel It),” which is almost a flag-waving

finale and the closest the record comes to a conventional rock song; the

wondrous “All I Need,” powered only by a slightly irregular heartbeat - as

atrial fibrillation finally takes hold, the song rapidly fades amidst a sheen

of Fairlight, giving us a frustrating glimpse of a future that lies beyond that

which this record implies; the staggering “No More Sorry,” its freeform drone fanfares

surely inspired by the closing section of Keith Tippett’s Frames and hiding one of the most frightening of all female vocal

performances, by Bilinda Butcher (“Filthy Daddy”); and above all the dazed “Lose

My Breath” which Butcher sleepily sings as though “rock” is slipping away from

her grasp – above all because it is a song about her infant son, Toby, and his asthma. Recorded largely in Wales, as

well as a couple of studios in London, over a two-week period on an average of

two hours’ sleep per night or early morning, Isn’t Anything is a gauntlet thrown down to the rest of rock of

which only the most superficial elements have since been picked up (one Mancunian, twenty-one years old in 1988 and transfixed by this record, springs to mind). I suspect

that a surviving forty-year-old Nick Drake would have wasted no time addressing

it.

(Envoi: perhaps the deciding factor is the seven-inch instrumental single which came with initial copies of the album. "Instrumental No 1" is a standard MBV "rock" backing track which evidently never received a lyric or any vocals. But "Instrumental No 2" plays like the ghost of rock retreating from the world altogether; wordless choruses - are they voices or effects boxes or both? - intonating a lament over a suspiciously familiar rhythm track. Why, it's "Security Of The First World" by Public Enemy, and it's a small world, after all.)