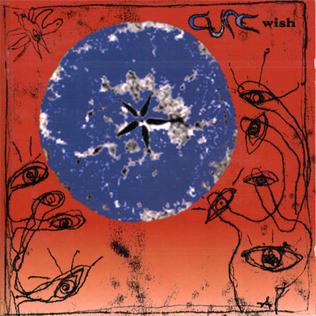

(#449: 2 May 1992, 1 week)

Track listing: Open/High/Apart/From The Edge Of The Deep Green Sea/Wendy Time/Doing The Unstuck/Friday I’m In Love/Trust/A Letter To Elise/Cut/To Wish Impossible Things/End

“I realize that for all my brave, bold talk of being self-sufficient, I realize now how much you mean me- you and Warren and my dear Grampy and Grammy! … I am glad the rain is coming down hard. It’s the way I feel inside. I love you so.

Sivvy”

(Plath, Letters Home, 27 November 1950)

“Don't turn around

I won't have to look at you

And what's not found

Is all that I see in you”

(Associates, “Party Fears Two,” February 1982)

The record – the music – staggers into reluctant existence. Drums and guitars initially sound askew but soon coalesce in collaborative collapse. As with “Whiter Shade Of Pale” and “Party Fears Two,” the song “Open” is superficially about somebody getting too drunk of a social evening, but its Plath citation indicates that this is merely a symbol of a deeper and possibly inaccessible sense of preordained doom. The geometric tracery that had been evident in The Cure’s music since Seventeen Seconds was very much present; in one sense the band do not seem to have changed at all in the intervening dozen years, and yet they are somehow more assured, more determined, more powerful and more terrifying – and that cannot simply be ascribed to the fact that there are five musicians here as opposed to the three there were in 1980 (two of which – Robert Smith of course, but also Simon Gallup – are still present).

How on earth did Wish – which bore the provisional working title of Swell – get viewed as a “lighter” Cure album? It was their only UK number one album, and I suppose it may have sounded marginally more penetrable than the gruelling – a little too gruelling for my tastes - arena of Disintegration three years previously. Yet it manages to plunge deeper emotionally than its predecessor, even though its thematic focus is equally narrow. There is nowhere on Disintegration where Smith falls apart, as such, but he certainly does so on “Open”; recorded at The Manor in Shipton-on-Cherwell, as was the rest of the album, the song is indeed as uncompromising an opening to a rock album as “Leave It All Behind” is to Wish’s contemporary, Going Blank Again by Ride.

Nonetheless, it is thoroughly relevant to cite Plath’s concept of duality as a central axis holding the seemingly divergent and at times contradictory nature of Wish’s dozen songs. This is what she says in the final paragraph of The Magic Mirror:

“However, our paper will conclude here with a reassertion of the psychological and philosophical significance of the Double in Dostoevsky’s novels. Although the figure of the Double has become a harbinger of danger and destruction, taking form as it does from the darkest of human fears or repressions, Dostoevsky implies that recognition of our various mirror images and reconciliation with them will save us from disintegration (my italics). This reconciliation does not mean a simple or monolithic resolution of conflict, but rather a creative acknowledgement of the fundamental duality of man; it involves a constant courageous acceptance of the eternal paradoxes within the universe and within ourselves.”

As well as explaining The Prisoner, this also outlines the strangely logical, if eventual, reconciliation with life as it is lived which Smith reaches in Wish. If anything, the record could have been titled To Wish Impossible Things (a curious counterpart to the “impossible dream” which materialises at the end of tomorrow’s entry); the song plays like a reconstructed, hollowed-out variant on the preceding album’s “Lullaby,” with drums being replaced by Kate Wilkinson’s careful viola.

Smith and The Cure also manage to reconcile the brutal and the delicate, since “Open” is immediately succeeded by “High,” one of the loveliest songs the band ever created, and the only instance here where Smith is happy without qualification or uncertainty; it was the album’s lead single, and if you have it on CD, you could programme the running order such that “High” came last, thereby providing a happy ending.

But after “High” comes the rather draining “Apart,” a pitiless exploration of a slowly-collapsing relationship. There are faults and misreadings on both sides which Smith explores in thorough and sometimes painful detail. “At The Edge Of The Deep Green Sea” – which itself inevitably brings Plath’s short story “The Green Rock” to mind – was, according to Smith, inspired by drugs, but once more we find acceptance of love battling against its reluctant rejection. “Nancy Time” goes even further, where a potential Other offers herself to Smith but he crossly (or camply; note the Quentin Crisp upward curl when he utters the “F” word) rebuffs her.

Both of these latter two songs are powered by strong, rolling beats which indicate that somebody had lent an ear to Achtung Baby and/or Screamadelica, and both bear an unanswerable certainty which was perhaps new to The Cure. No doubt they may also have had American FM rock radio airplay in mind (and if so, it worked, since this album went platinum in the States and sold a million), but these are the confused children of Three Imaginary Boys and Faith grown up and multiplied.

The album does appear to lighten up momentarily after that, even though “Doing The Unstuck” tempers its sunny-day-wake-up-smell-the-roses ideations with the suggestion that this state of being will only be achieved by burning down everything the song’s subject knows. As McCartney had been with “Yesterday,” Smith was convinced that “Friday I’m In Love” already came from somewhere and had to be firmly reassured that its structure was his own. In this context it is almost a parody of an upbeat pop song – that strange middle eight where his lover eats in the middle of the night – and was cut a quarter-tone above concert pitch to enhance its boyish bounciness.

Thereafter follows the plaintive and profound “Trust” – grand instrumental architecture bookends a brief plea by Smith to continue existing, uncertain whether his Other will respond – and the closing four songs examine, in the manner of The Lexicon Of Love, the essential and unbridgeable duality between an ideal of pure love – possibly romance is a more helpful term here – and the less glamorous but ultimately more durable reality of love as it is lived. “A Letter To Elise” builds as methodically and dramatically as a peak-era Def Leppard power ballad – not a farfetched notion – as Smith looks through the mirror and does not see what he recognises as “love.”

“Cut” might be The Cure’s most brutalist moment; unsparing, noisy, propulsive, as though a decade of incremental pain had suddenly been let out in a single, extended scream (ex-Cure roadie Perry Bamonte, now promoted to co-lead guitarist, is particularly outstanding here, as are stalwart Boris Williams’ drums). But the closing “End,” is extraordinarily prescient – the band’s rock once again heaves and staggers; yet, as guitars clang and the rhythm unmissably swings, and Smith repeatedly howls “Please stop loving me!,” one is reminded of a band new at this time, who originated not far away from The Cure – Haywards Heath as opposed to Crawley – and who are set to explode over Then Play Long imminently (entry #476). Hello young Brett, coming in through the door that Robert left open…

“Teach me half the gladness

That thy brain must know,

Such harmonious madness

From my lips would flow

The world should listen then, as I am listening now!”

(Percy Bysshe Shelley, the twenty-first and final verse of “To A Skylark,” the eighteenth verse of which is quoted on the sleeve of Wish, June 1820. The poem was published in conjunction with his four-act lyrical drama Prometheus Unbound; well, fancy that!)