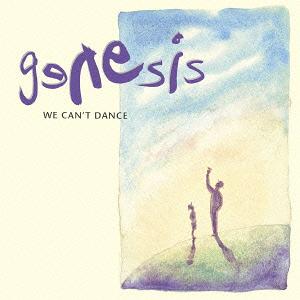

(#441: 23 November 1991, 1 week; 22 August 1992, 1 week)

Track listing: No Son Of Mine/Jesus He Knows Me/Driving The Last Spike/I Can’t Dance/Never A Time/Dreaming While You Sleep/Tell Me Why/Living Forever/Hold On My Heart/Way Of The World/Since I Lost You/Fading Lights

They are pictured sitting glumly in the remnants of an office Christmas party, or perhaps a works Christmas disco – they can’t dance, you see. Phil Collins in particular looks as though he’d rather be anywhere else, and was presumably wondering what the hell he was still doing there, with this Genesis lark.

We Can’t Dance was the final Genesis studio album to involve Collins, after a long layoff – well, Phil had his own album to do – and everything about its seventy-one minutes and thirty-eight seconds suggests weariness and contractual obligations. Little of it sticks, so much so that its inoffensiveness ends up being offensive. There is nothing here even worth getting annoyed about, and much of it grates in the manner of a Guardian columnist, including, as the album does, tirades, or should I say mild protests, about child abuse, television evangelists, nineteenth-century immigrant Irish railway workers (but Collins is no Stuart Adamson or even Sting), hit-and-run drivers, the Gulf War and the fashion and wellbeing industries. “Since I Lost You” is about the accidental death of Eric Clapton’s young son Conor but is no “Tears In Heaven.” The grim conclusion? Why, it’s the “Way Of The World.” Put up, don’t pay your taxes, vote Conservative and shut up. Such lyrical references as “Do you really want to live forever?” and “These are the days of our lives” suggest familiarity with the later works of Queen.

The ballad of love-fuelled indecision “Hold On My Heart” works to a point because one feels that this is something Collins is actually experiencing, that he needs to communicate – the band always worked best when trying less hard (“Many Too Many,” “Man On The Corner,” “In Too Deep”) – and I am only sorry that Miles Davis didn’t live long enough to cover it. Similarly the lengthy closer “Fading Lights” is cumulatively quite affecting, since its very prolonged and gradual fadeout suggests the lights going out on the band, the end of their road, a modest farewell.

We are not finished with Genesis yet – I did emphasise at the top of this piece that this was their final studio album in that form – but apart from avidly loyal fans, stray Valium Court housewives and Alan Partridge/middle management types I cannot imagine who would be attracted and moved by this far too long and generally eventless album.

Perhaps it should have swapped titles with another more significant album which came out the same day.

For such an acclaimed record, it is interesting, if not especially surprising, that so little of use has been written about Loveless. It is that monument, too vast to avoid but which people are generally too scared to penetrate and explore.

Most online writing does not concern the album, as such, but rather its prolonged making. Reviews are heavily prefaced by recycled information about the record’s conception – stories which are so well-known there is no point in my repeating them here – but when it comes to the music itself, I suspect most writers simply do not know what they can say about it; hence we get indie generalities and/or below par prose poems.

When initially released, Loveless became lost in the pre-Christmas market maelstrom, peaking at #24 and spending only a fortnight in the charts. At the time Creation lacked the promotional and marketing resources which could push the likes of Genesis up to a broadly regular number one, but then again at the time, as is exhaustively documented, Alan McGee had had his fill of My Bloody Valentine and what he saw as their slacker spendthrift ways.

Reviews at the time were, in general, guardedly favourable but cautious – both the late Dele Fadele in the NME and Simon Reynolds at Melody Maker expressed reservations. Even on a Creation Records scale it lacked the primary-coloured nowness of Screamadelica or the affable warmth of Bandwagonesque. People didn’t and still don’t know what to do with the record; it has to date sold only about 250,000 copies worldwide, and radio continues to avoid them carefully – even BBC Radio 6Music generally tiptoes around the group’s assumed status.

There is little, if anything, which might describe to you how Loveless makes people feel, where it came from and where “rock” might be going from it as a result. So allow me to try.

Listening to the record now, as was the case then, I am primarily struck by how calm an album Loveless is. There is little, if anything, of the turbulence expressed by its predecessor (or its attendant E.P.s); violet appears to have succeeded violence. What has not changed in twenty-nine years is that I have no real idea of what Kevin Shields and Bilinda Butcher are singing about in these eleven songs, nor do I want to know. The overall, total experience is what is made to matter; much like the group’s countrywoman Enya, there is a residual concern not to have to express oneself too clearly or to be understood too quickly.

We could talk, in a vaguely deathly manner, about influences. When Butcher’s voice is to the fore (“Only Shallow,” “Loomer,” “To Here Knows When,” “Blown A Wish”), the Cocteau Twins are profoundly visible in the music’s middleground. Even on “Only Shallow,” however, “rock” is compelled to stagger, never quite in focus, perhaps even delirious (but more of the latter in a moment). How courtly a song “To Here Knows When” is – so much more romantic than Sunday morning radio’s notion of love songs, since (as the Jesus and Mary Chain and A.R. Kane had already indicated) the essence of love lies in the prospect of being swept away, losing all cold claims to ratonalism. Its air seeps through processed gateposts of reverb pedals and glissandi tropes to convince the listener that nothing of the world exists except this rapture of nowness. Hold on, my heart, indeed.

Such songs as “When You Sleep” and “Come In Alone” play with the idea of rock as though the music had started with Dinosaur Jr’s “Little Fury Things” rather than “Rock Around The Clock.” It is as though they have intentionally gutted the masculine corpus of rock and replaced it with a feminine fluidity, and this “feminisation of noise” goes back to the days of Ornette Coleman (or perhaps “democratisation of noise” would be a more apt description). This music from one perspective does not sound as though played by humans, but from another perspective could not be more human.

(One important forebear in the “look-no-apparent-hands” school of guitar treatments might be Keith Rowe in the politely noise-democratising AMM, and this link was indeed confirmed when Kevin Shields subsequently teamed up with Eddie Prevost, Pete Kember a.k.a. Sonic Boom [of Spacemen 3, Spectrum et al] and Kevin Martin [God, Techno-Animal, The Bug &c], in the improvisatory collective Experimental Audio Research.)

There is a new loveliness at work; the lullaby of “I Only Said” could go on forever, while “Blown A Wish” bears a sublime chord progression (the bump in the Yellow Brick Road from E major to D major Add 9, and then back to E major over “Try to pretend it’s true,” “I’ll be the death of you” and so forth – in other words, when the song turns around to reveal its true nature) worthy of McCartney.

From another perspective, in “Sometimes” – another seemingly eternal cycle – one can clearly hear Oasis attempting to break through (I have a LOT more to say about Oasis and their semi-acknowledged debt to MBV as this tale progresses). But, after the flag-waving singalong “What You Want,” the album itself breaks through its self-constructed shafts of sunlight obscurantism.

The finale is the 1990 single “Soon,” indie-dance which feels independent of dancing with its inspired systematic shifts from cyclical brightness to what is actually (come to think of it) fuzzy violence, and yet manages with some confidence to break the ceiling which so many would-be Loveless lovers might find a tad suffocating. The song blossoms and then fades forever, but unlike Genesis, not to nothing.

I have of course thought; why the “noise,” the unlit pillars of effects and distortions, when they are covering such a plaintively melodic record? And then I thought back to the summer of 2018, and now think I understand:

On the ward after coming out of Intensive Care, endlessly wheeled back to theatre for regular internal dressings changes, under the conflicting influences of anaesthetics, antibiotics and morphine derivations, I lost all sense of reality, could not distinguish between lucid fantasy and pellucid truth. I heard in the distance a radio station booming out music, the likes of which I had never heard. Deep dub, distorted overlying crackles, a hugeness of sound, an agreeable discontinuity of expectations and form. What was this station? It wasn’t on my digital radio. It must be online; somebody has hooked it up to a speaker. It was impalpable yet transcendent.

I was humoured. The station and its music did not exist. When I regained some sense of reality I discovered that somebody had on Smooth FM, and it was playing “The Way It Is” by Bruce Hornsby and the Range.

By the window, thirty-nine degrees and no wind, I look towards the window but cannot turn towards it. The electric fan, permanently switched on, offers little respite. I feel as though I am expiring. Somewhere in the haziest of distances I perceive a spear from the sky. It is Rod Stewart singing “Forever Young.” What exit music. And an exit to where?

When music is at a distance and you cannot quite make it out but you realise that it is singing to you and was meant only for you.

“I do not ask for anything I do not speak

I do not question and I do not seek

I used to in the day when I was weak.

Now I am strong and lapped in sorrow

As in a coat of magic mail and borrow

From Time today and care not for tomorrow.”

(Stevie Smith, “I Do Not Speak”)