(#484: 17 July 1993, 1 week)

Track listing: Zooropa/Babyface/Numb/Lemon/Stay (Faraway, So Close!)/Daddy’s Gonna Pay For Your Crashed Car/Some Days Are Better Than Others/The First Time/Dirty Day/The Wanderer

The facile thing to say here is that it was nice of Eno to allow U2 to appear on their own album. It would indeed be a facile and stupid thing to say, since alleged unaffectedness requires over-affection to balance things out and make itself recognisable.

But there are reasons why I am writing about this album and not about Achtung Baby, and the naivety of competing with a Michael Jackson album isn’t the only one. Achtung was essentially a Daniel Lanois album, whereas Zooropa – which built up from a proposed E.P. to admit a stream of ideas which had accumulated during the band’s Zoo TV tour – quite clearly frames Eno’s recaptured concept of what U2 should be. “Clearly” because the sound on Zooropa is fantastically clear when compared with the deliberate muddiness of its predecessor, as though the curtains have been opened and light – even of the neon variety – has been allowed into the room.

Was it U2’s Low? I would say not, because despite some confusion (“I have no compass, and I have no map,” “Uncertainty can be a guiding light”) and occasional thematic crossover (“Daddy’s Gonna Pay For Your Crashed Car” doesn’t really sound anything like “Always Crashing In The Same Car,” but “The First Time” might sound something like it – although a great deal more like “All I Want Is You,” and therefore “Ocean Rain”), they have elected to revel in the absence of clarity and direction, give themselves up to a brighter and greater future.

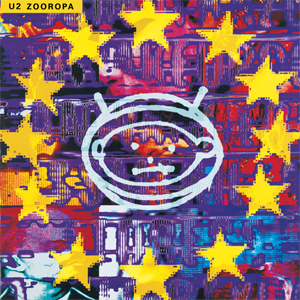

And that future, as implied in the album’s title and spelled out on its cover, was to do with a greater Europe. Bono in particular wished to offer a portrait of a happy and harmonious future for the European Union than the edgelord-unfriendly dystopia which so many people thought and perhaps wished Europe was.

Hence the title song, which commences the album, begins with a melancholy cycle of descending piano chords (which in themselves not only echo the closing moments of John Zorn’s “Spillane” but also foreshadow the subsequent careers of Coldplay and Keane) set against some semi-random radio snatches – and then the feeling that we have been somewhere like this before.

The band themselves – to a point; it’s Larry Mullen playing that introductory bass – then enter the picture modestly before the song suddenly explodes into light, that thunderous, tumultuous statue of syndrums reminding me of yet another awesome but frightening dream*

(*I am in Oxford, buying some groceries in a supermarket, probably in the Westgate Shopping Centre. I go out and realise I have left my grocery bags in the store, so retrace my steps but cannot quite find the store again.

Then I suddenly and inexplicably find myself on a bus, travelling through the city; in the middle distance I see a bridge leading to an enormous, glittering cityscape which looks like a new financial district – is that how long I’ve been away from Oxford? The bus does not travel there but halfway through my journey the lights on the bus are suddenly extinguished and the windows are automatically darkened. I can just about make out what we’re passing through – it is clearly a military base – and I see enormous, unanswerable missiles and bombs standing in attentive line. This is a preparation, I realise, for the end of the world, and the large syndrum tropes on “Zooropa” remind me of this enormity which will not be argued with.

A great deal of Zooropa’s attraction – as was the case with Black Tie White Noise – lies in its somewhat unreal nature; one feels, as with Bowie, that U2 are participating in a vivid and lucid dream. Now that I have had direct experience of the latter, I understand this super-real nature far more instinctively.)

Getting past the deliberately creepy lullaby of “Babyface” – far more worrisome than anything on Disintegration – we get to “Numb,” an adaptation of a song entitled “Down All The Days” which was left on the Achtung cutting room floor, intoned by The Edge with Bono’s falsetto quivering in the middle ground, perhaps a Parallax View notion of benign indoctrination; the seemingly unending “Don’t”s are horribly reminiscent of the forced mustn’t-grumble/motivation pabulum with which we have been supplied these last eleven months – except that the one instruction, or request, is “Suggest.” An escape hatch has been left open; it's up to our determination and ingenuity to locate it. And yet it also encapsulates, and anticipates, the computerised sensory overload which, a generation later, threatens to drown and devour our species.

(Actually The Edge's voice here sounds rather like Mike Love; whisper it...)

“Lemon” is a glorious addendum to Remain In Light; that same reverse sashay of descending bass notes and intraoperative percussion, and a lead vocal which is quite patently recalling Billy Mackenzie (this could SO have been an Associates record), at least until Eno (assisted by The Edge) politely takes the song over with his philosophical recasting of James Brown (“A man builds a city/With banks and cathedrals” etc.) – or so you think, until you realise that the song is about Bono’s mother, and an old Super 8 home movie taken of her playing rounders, in a time when things were allegedly less complicated (that slightly-flanged drawing room piano in the bridge again – of course the teenage Chris Martin was paying attention).

It really isn’t that far from “Death Disco” (see also the uncanny – or is it really uncanny at all? – resemblance of “Numb”’s main melody and rhythm to the venerable Irish jig) yet it asks us to reclaim memory rather than merely lament its absence. Side one finishes with the superlative “Stay (Faraway, So Close!),” written with Sinatra in mind but ultimately passed on to Wim Wenders for use in his seldom-discussed sequel to Wings Of Desire – an immense and subtly very hurting song (it may centre on the theme of domestic abuse – “You say when he hits you, you don't mind/Because when he hurts you, you feel alive/Oh no, is that what it is?”). But the angel can only shadow her comings and goings, and the final, resigned cymbal crash is like wings dissolving into flake – is that all there is?

Side two sees the band walking out into a 1993 which is as ominously and abruptly mysterious as falling asleep on the coach and waking up at two in the morning at the entrance to Heathrow with its gigantic, neon-lit advertisements – is this “the world”? “Daddy’s Gonna Pay…” successfully negotiates a chasm between Russian folk songs and MC 900 Ft Jesus (both are sampled). “Some Days…” sounds Mancunian in nature, but far more like MC Tunes than the Smiths, slippery, elastic and bouncingly funky.

“The First Time” is one of U2’s most profound ballads – so slow and patient in its building towards its unexpected anti-climax; the Prodigal Son, in the end, opts not to return home, and has not quite worked out whether he considers that a good thing; as piano and Eno’s La Sagrada Familia cathedral of synthesisers widen the song’s pictorial scope. This time, Number 6 knows better than to expect a fatted calf on his arrival.

“Dirty Day,” which really isn’t that far from a grown-up “Kinky Afro” – except that the song is being sung by the son, rather than his father – is so stealthy yet so explosive when the need presses. This might be the returning wanderer, but Bono’s closely-miked voice palpably trembles and is unashamed to admit baby cries. It is a song of despising.despair (“ You can't even remember/What I'm trying to forget” – the protagonist of “Stay,” perhaps?).

Bono has little to say after that, and instead gives up the final, and possibly the album’s most disturbing, song to Johnny Cash, absent from Then Play Long since 1972 (or should that be 1969?), who was visiting Dublin at the time and was asked by the band to contribute. Not only does “The Wanderer” negate practically all of the phoney nostalgia implanted into Rattle And Hum, but it also sums up this album’s themes; of paternal desertion and reluctant return, the impossibility of discerning reality in a sea of glass and tin commercialism dependent upon sustained fantasy, the Biblical subtext which will simply not vacate U2’s minds, and…much worse…the possibility that this is all taking place after the apocalypse.

More than the Bowie of “Subterreaneans,” this furnishes a picture of, say, visitors from Mars arriving on Earth – or was it just WALL-E all along? – and wondering, as with the protagonist of “The Shifting, Whispering Sands” (more Eamonn Andrews’ version than Ken Nordine’s, I’d wager), just who or what ever lived here - or it is a disappointed Jesus searching in vain for an unwanted sunbeam?

Then you think the album has finished, but in come those static bleeps, curiously reminiscent of “Spirit In The Sky” – that’s where we’re gonna go when we die? – which in turn are cruelly cut off by a screeching car brake.

Is it any wonder sometimes that you don’t leave your room?