(#457: 29 August 1992, 1 week)

Track listing: This Charming Man/William, It Was Really Nothing/What Difference Does It Make?/Stop Me If You Think You’ve Heard This One Before/Girlfriend In A Coma/Half A Person/Rubber Ring/How Soon Is Now?/Hand In Glove/Shoplifters Of The World Unite/Sheila Take A Bow/Some Girls Are Bigger Than Others/Panic/Please, Please, Please, Let Me Get What I Want

“I never made a cent from these photos. They cost me money but kept me alive.…”

(Dennis Hopper, Out Of The Sixties. Pasadena, Twelvetrees Press: 1986)

“But don't forget the songs/That made you cry/And the songs that saved your life…”

(The Smiths, “Rubber Ring,” 1985)

“One of our group was sporting a t-shirt he’d had printed that read, ‘We all agree…’ on the front, and ‘…Morrissey’s a wanker!’ on the back. The t-shirt was to prove a talking point among any fans that saw it throughout the day, and much head scratching was done as to the choice of the former Smiths man in the line-up. The common consensus was that he didn’t have a place there, which of course was later borne out in spectacular and well-documented fashion.”

(Madness fan Graham Yates, reminiscing about the Madstock! concert on Saturday 8 August 1992, from the article “Madstock Memories” as featured on the Madness website Seven Ragged Men)

Morrissey was not supposed to appear at the Madstock! festival; he had only been added to the Saturday bill at a very late stage, and many Madness fans were disgruntled by his inclusion. In fairness, neither of the opening acts, Flowered Up or Gallon Drunk, made much of an impact, except that the latter had plastic bottles and suchlike thrown at them. However, special guests Ian Dury and the Blockheads went down a storm, Dury being an experienced and empathetic showman who knew how to work a crowd.

When Morrissey went onstage, however, the huge crowd were becoming impatient for the main attraction, and gave him comparatively short shrift. Disgruntled, the singer, clad in provocative (to this crowd) gold lamé, cut short his set and unfurled a Union Jack during the song “Glamorous Glue.” In truth he was jeered rather than bottled off the stage. But he had a newly-released album, Your Arsenal, to promote, and the inclusion on the latter of songs such as “National Front Disco” further fuelled the fire of presumed racism. The NME in particular jumped on him in that respect.

We may revisit this fatal flaw of Morrissey later. But it is worth observing that he, and the Smiths in general, did not carry as much critical weight at that time as hindsight might presume. When WEA acquired the rights to the band’s back catalogue from Rough Trade in early 1992, cries of “sell out!” echoed from their residual followers. The band who had pointedly not played the majors game within their lifetime had been bought out by the majors.

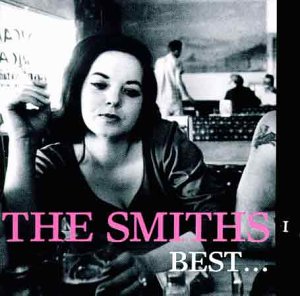

Best…I, the first of two proposed compilations of the Smiths’ work, was released in approximate conjunction with their promptly-reissued back catalogue. It was obviously popular to a point – otherwise I would not be writing about it, or them, here – but was generally decried. Its appearance in the record racks a mere three weeks after Your Arsenal did not exactly help either. The track selection was condemned as random, uncoordinated and corporate. There was no “Cover Star” credit, as had been the custom on previous Smiths releases (although, interestingly, the cover, taken from Dennis Hopper’s 1961 photographic study “Biker Couple,” was only used for British and European versions of the album – the American cover was designed personally by Morrissey, and featured the actor Richard Davalos). There was obviously some cooperation, since the song lyrics are reproduced “by kind permission” and are as originally written (“NO, I DON’T WANT TO SEE HER,” “IT SAYS NOTHING TO ME ABOUT MY LIFE”).

Hence Best…I was damned as commercial compromise. In WEA’s defence, it should be noted that at the time, because of the collapse of Rough Trade, the group’s work had drifted out of print, and WEA worked assiduously to make all of it available again. To promote the album, “This Charming Man” was reissued as a single, complete with Jean Marais sleeve, and made the top ten almost nine years after it had unaccountably peaked at a mere #25. They were doing their best.

But who was Best…I’s intended audience, and what really was the album’s purpose? There was nothing on it which wasn’t readily available on other Smiths records; even the single version of “This Charming Man” was appended as a bonus track to the CD reissue of their eponymous debut album (at least on American copies, one of which we have), so it can’t have been aimed at their core fanbase. Was it intended to win over undecided waverers? If so, that didn’t work either; the album went gold but disappeared from the chart after nine weeks.

Was it for premature nostalgists, those who had heard tales of the band in the eighties but hadn’t quite been old enough to go and see them or buy their records at the time? We know that by 1992 people were already missing the previous decade. Did it serve as an inadvertent harbinger of what was to come imminently from British guitar-based music?

It is a difficult and probably impossible question to answer. Most people in the nineties’ idea of Manchester music drifted serenely from Simply Red to Oasis (even though the Smiths cast a gigantic foreshadow of what the Gallaghers would go on to do). Why would affluent people in their late twenties or early thirties feel nostalgic about music which, when it was happening, was generally laughed at and ridiculed? The Smiths did not have the popular vote when they existed. They were always seen as music for weirdos, and unlike Ziggy Stardust in the previous decade they demonstrated no urge to cross that particular bridge. In their lifetime, most of their singles peaked in the mid-twenties or at best the mid- or upper teens; they only had two top ten hits, both of which peaked at number ten. This can’t all be blamed on Rough Trade’s legendarily crappy distribution set-up. John Peel famously described the singles charts of the mid-eighties as, basically, “a Radio 2 chart” – which most likely explains the continued, aggressive pushing of that decade’s mainstream pop by that radio station today – where anything straying even slightly from the opulent, treble-heavy Fairlit formula was automatically damned and sidelined.

No, the Smiths were always about, and for, those who didn’t buy the whole Maggie-tastic aren’t-we-nobly-great? nouveau riche regimen. Some might even term them the pop group for those whom Thatcherism had left behind. All of which makes Best…I a very puzzling collection.

It is puzzling because, as you can see from scanning the above track listing, this is not a particularly obvious “best-of” anthology. Many of their most famous songs are conspicuously absent. Listening to it, however, I cannot agree that it was a cynical, random cash-in in the line of the Stones’ Sucking In The Seventies, put together in ten minutes by drawing the names of various Smiths songs out of a hat without thought for context or continuity. If anything, it is a connoisseur’s assemblage of Smithiana, and its appearance was rather akin to what might have happened if More ABBA Gold had been released ahead of its predecessor (of which latter, more anon in this tale).

The remastering process cleared up a lot of the muddiness in the original mixes and the band sound much punchier in their impact. So they sounded better here than they had done on record for some while. The record begins with “This Charming Man,” that immense and unavoidable “SHAN’T” inserted into the 1983 pop discourse. What strikes me about it now is how close it is to a sixties Motown song – listen in particular to Andy Rourke’s bass (like Peter Hook, Rourke frequently takes the lead lines) which is clearly modelled after James Jamerson (who had died ignominiously just three months prior to the single’s original release). The song swings, rather than jackhammering its way through one’s wallet, and the ineffable elegance of the vocal line and the song’s lyrics – telling a story being more important than scansion – recall Gilbert O’Sullivan more than they do Noël Coward. It suggests sex rather than thrusting it in one’s face like a rainy Thursday morning on Berwick Street. What is held back is as important, or more important, than what is declared; a tactic Morrissey learned from his friend Ludus (“Does my objectivity/Allow me access to your points of view?/Can you see what I see in you?” – from the Ludus song “Sightseeing”). It bounces rather than throbs. If its counterpart “Blue Monday” buried a manifestation of New Pop, “This Charming Man” acts as a revitaliser, much as its contemporaneous distant cousin “Moments In Love” also did. The pivotal yelp that Morrissey gives seems to declare: “begone, JoBoxers!” Marr is the real Johnny Friendly here. Everything on the record breathes lilac like a premature spring.

The songs are assembled with logic rather than chronology in mind, so “William” here comes as almost light relief, particularly when Morrissey begins to impersonate the singing style of the song’s presumed subject at its end – and the backward slopes of guitar ushering the brief song out underline how reluctant Marr, or indeed John Porter, was simply to end the song; both understand the structural dynamics which make pop records work (see also Mike Joyce’s two leapfrogging, rhetorical snare drum tattoos). Next to that, “What Difference Does It Make?” sounds almost chaste in its rockiness, though musically does bear a remarkable kinship with the more thoughtful work of Status Quo (“Forty Five Hundred Times”); again, the school playground sound-effects two-thirds of the way through the song are skilfully deployed – this isn’t quite rock music which can be replicated on a stage.

There then ensues a jump cut to 1987 and “Stop Me,” with its much more assured and certain lead vocal and Marr’s guitar taking a clear creative lead, and, from the same time, the melancholy and contradictory “Girlfriend In A Coma,” whose ambiguous meditations might make more sense if viewed from the perspective of a song being sung by a potential murderer.

But then it is back to “Half A Person,” a simple lament for a failed and all too readily explicable life (five seconds to fit in “sixteen, clumsy and shy”) at the end of which Marr’s guitars envelope and embrace the singer (even after his exit from the song) as surely and profoundly as did Anne Dudley’s strings do with Martin Fry’s exhausted grief on “All Of My Heart.” One of the Smiths’ gentler and deepest songs, the hand stretched out to those eighties capitalist rejects, or Rechabites, to welcome, to understand, to empathise, to connect. That in turn gives way to “Rubber Ring,” one of their saddest and perhaps angriest songs – although this is likely unfair, since Morrissey is gently chiding, all the better to disguise his pleas. It is as though he is singing to those Smiths fans who will go on to prosper (become, in his words, clever swines), urging them not to forget him or this music, these songs which kept you going when nothing else in the world would or could. The importance of the paradoxical permanence of a fundamentally transient form of entertainment, and maybe the reason why people keep going back to the old songs, have particularly done so in the past year when everything else has appeared so unforgivingly terminal. Never forget me, what I once represented in your life, in our lives…all the while, the T. Rex twist of rhythm builds up, as does the Martin Carthy-esque wordless refrain, as strings, guitars and samples steadily encroach on the song before all is suddenly cut off, like a life support machine being disconnected

(and yes, I have a significant personal bearing on all of this, but I can’t tell you everything; not just yet, anyway..)

“How Soon Is Now?,” that song of hopelessness on the part of its singer, which its guitarist manages to convert into a song of hope; perhaps their finest achievement, which spells out firmly why U2 saw them, and not the Bunnymen, as their main rivals. The slightly, if understandably, petulant tenor (because the petulance is based on fear of evaporating) of Morrissey’s voice (which is properly a baritone rather than a tenor) is compelling – he is demanding to be loved, not to be ignored or left to wilt with the other flowers on the wall of the dance hall – but it is answered fully by Marr’s almost hands-off guitar playing, with its many subtle overdubs (why are there so few of you, the guitarist appears to be asking, but so many of me?). The rhythm is Bo Diddley, the guitar lines are John McGeoch fed through Charlie Burchill – and Rourke’s active bass commentary reminds you just how much this performance owes to Simple Minds (“Seeing Out The Angel,” anyone?). The grinding core of the song could conceivably go on forever, but fades discreetly after some six-and-a-quarter minutes. Towards the end, Morrissey even indulges in some cheerful whistling, as though this is his “Everything’s Gone Green,” his eventual rebirth from the ashes of apparently unanswerable despair.

There follows the lovely defiance of “Hand In Glove” – the full version, not the 45 edit with its fade-in and fadeout – where Morrissey challenges the New Pop castaways of 1983: “you CANNOT be happy with just THIS!” As gloriously fuck-you as “Love Me Do” had been in their parents’ age – why else the harmonica? – it stops and starts with balletic grace. Even, or especially, Mike Joyce’s one-bar-behind-the-beat fluff towards song’s end makes the record endearing; this is so NOT Kajagoogoo. In May 1983 it felt coldly (but also warmly) radical.

Back to 1987 for the sort of glam rock which was still embarrassing too many otherwise potentially useful people, albeit still with a pronounced and inherent Irish gait: hence “Shoplifters” presages the freed U2 of Achtung Baby and also makes me wonder what that other Irish misfit Kevin Shields would have made of its glide. “Sheila Take A Bow,” from its sampled brass band introduction to its Bobby Crush piano lines, all built on an undertow of pure Bolan, would have been number one for five weeks in 1972, and the reason it wasn’t is, I’m afraid, our fault. Note also the interesting juxtaposition of the line “Throw your homework onto the fire” with what Michael Hutchence sang on “Heaven Sent” (“Don't burn the library ‘till you've read all the books/Sometimes in life you get a second look”).

“Some Girls” is an unlikely successor; the closing and possibly the most disquieting song on The Queen Is Dead, which runs through what sounds lyrically like an old Will Hay music hall romp that Marr is escorting to another planet entirely, so much so that Morrissey ends the song, and that album, with a murmured Johnny Tillotson paraphrase, as if to promise that life is eternal. “Please, Please, Please,” which concludes this album, sounds like a centuries-old English folk song - note Morrissey’s very precise enunciations of its lyric - suddenly hijacked by a caressing concubine of mandolins, answering his prayer for things to go right for him just once in his wretched life.

But, as you can see, I have left out “Panic,” their most problematic song, and I think included here for purposes of deliberate disruption. Yes, it was one of their biggest hits (if number eleven counts as “big”), but it outlines that fatal flaw I mentioned above, Morrissey’s modest proposal to wage war against anything that isn’t him. Define yourself as against the masses, if you will (though that usually conceals a profound underlying love of them), but declaring war on pop, or, worse, discos (were there still such things in 1986? First-hand evidence suggests that there were not), was a gesture of provocation which cast all of the wrong shadows and in its part helped lead to the mess in which we find ourselves today. Morrissey gave an interview to Melody Maker around the time of “Panic”’s original release where he decried black music in particular. At a time of “Kiss,” “Nasty,” “Word Up” and “Love Can’t Turn Around,” among many, many others (“Sweet Love”? “PSK (What Does It Mean)?”? “Who The Cap Fits”?), this was a particularly unwise and foolish gesture to make, and it set many of the band’s followers, and therefore also those of “indie rock” in general, against black music in ways which I feel have proved destructive.

And this warped mindset is exactly what led to the events at Finsbury Park on 8 August, when Morrissey proved that contrarianism in itself wasn’t enough, and at worst was sorely less than enough. Hence, in August 1992, the Smiths, and Morrissey in particular, continued to be punctuated by an involuntary aesthetic question mark. The inside back page of the CD booklet features a trailer for something called ...Best II. The cover appeared to be the other half of Dennis Hopper’s biker study – “Half A Person,” you see – and the proposed track listing includes most, if not all, of the songs which you might be puzzled to learn are absent from this particular album. Perhaps they should have put out both as a double and have done with it. Instead, ...Best II sloped out in November of 1992 – and peaked at #29.

One of the songs Morrissey was fond of covering on stage at around this time was “My Insatiable One” by Suede. I think everyone was just waiting for the next chapter to commence, for the picture to be rendered complete.