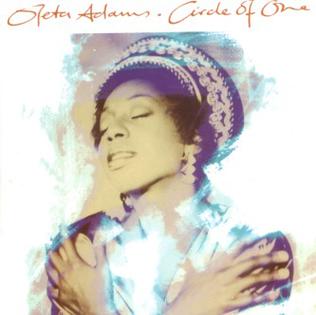

(#423: 2 March 1991, 1 week)

Track listing: Rhythm Of Life/Get Here/Circle Of One/You’ve Got To Give Me Room/I’ve Got To Sing My Song/I’ve Got A Right/Will We Ever Learn/Everything Must Change

(Author’s Note: The CD edition of the reissued version of this album – i.e. the one which reached number one – contains two additional tracks: “Don’t Look Too Closely” and a remix of “Circle Of One” by one Yvonne Turner. Both are pleasant enough but add little to the overall story which I believe the record is trying to tell.)

“Hell hath no limits, nor is circumscrib'd in one self place; but where we are is hell,

And where hell is, there must we ever be.”

(Christopher Marlowe, Dr. Faustus)

“…the fact that there are men with homemade dungeons, all ready and waiting, lots of them, the fact that they wait to capture girls, poor Fanny Adams, “Sweet Fanny Adams,” the fact that they have babies with the girls and then they kill the babies, my grandkids, the fact that so many men are merciless, heartless, Lanza, Breivik, Trump, Bill Clinton, Lolita Island, sex slaves, trafficking, porno pics, ISIS, beheadings, 9/11, 911, Oprah, Lee Harvey Oswald, ♫ The Stars and Stripes forever ♫, for no reason, for no reason,”

(Lucy Ellmann, Ducks Newburyport, p 828)

It has taken me almost four years to come back to this place. I think we all know that we have been living in a displeasing vacuum since last I was here. There are stories I could tell you about what has happened with, and to, me since the end of 2016. We have generally crouched in a foetal position of impotent rage masked by scarcely endurable politesse as smugly recycled feudal lords have cheerily, steadily and purposely dismantled everything you and I were brought up and taught to believe and cherish. In the centre of 2018 I lay in hospital, and for some of that time I have been told I was close to death. There remain six weeks for which I cannot properly account. It was akin to a prequel of the afterlife. I did indeed pass through hell, as one of the consultant surgeons who operated on me confirmed to me. I endured what the Intensive Care consultant described as “state-sponsored torture.”

There was no opting out of the latter, however; it was either state-sponsored torture or death. Yet, as a consequence of needing to return repeatedly to theatre for dressings changes – the estimate at the time of my discharge was that I had been taken to theatre some 30 or 40 times – and the required, conflicting dosages of anaesthetics, antibiotics and morphine derivés, I lucidly saw and experienced things no human being, even the one you loathe most, deserves to have experienced or seen, even though they were only being experienced inside my head.

Now, imagine that scenario being repeated ceaselessly in the minds of millions, if not billions, of your fellow humans. The notion of everything good about the human species being happily stamped upon. The feeling that the final pages of our history were in the unalterable process of being written. The use of a pandemic – engineered by fatal greed and arrogance exhibited against nature – as a bludgeoning tool to expedite our extermination.

The sense that there was no way out.

Then, a mere two days ago, the curtain was abruptly dropped, and we saw and absorbed the façade for what it had always been.

I knew on Saturday that it was time to renew this story and write about this record.

* * * * * *

Born in Seattle but famously discovered playing the piano and singing in a hotel bar in Kansas City, Oleta Adams was spotted by the two members of Tears For Fears while they were in the USA touring Songs From The Big Chair. Two years later they remembered her and invited her to collaborate on The Seeds Of Love; such was her impact on the latter that the band’s record label offered Adams her own solo recording contract.

Circle Of One didn’t do much business initially – Adams had previously released two self-financed albums in the early eighties, but these were only distributed locally – but its third single sent it and Adams’ career through the metaphorical roof.

Adams had heard the original 1988 version of “Get Here,” performed by its author Brenda Russell (who was born in New York but grew up and worked as a musician for some years in Toronto), in a record shop in Stockholm and liked it enough to record it herself. Its release as a single coincided with the abyss of the Gulf War, and so its words – the song was the most convincing Canadian list assemblage since Hank Snow’s “I’ve Been Everywhere” – took on an extra layer of meaning. Adams sings it with vulnerable authority, but the real supporting dialogue here is with the rhythm section, in particular John Cushon’s drums, which for most of the song offers little more than a very reluctant and periodic heartbeat before finally beginning to assert itself in the performance’s closing ninety seconds (it is almost as if the drummer is playing the part of the lover whose company, and perhaps salvation, Adams is craving). Pino Palladino’s bass meanwhile trundles along, offering rubber-souled support.

The presence of Palladino indicates the very 1990 nature of Circle Of One. Recorded in London and produced by Tears For Fears’ Roland Orzabal, with Dave Bascombe (and a minimally-credited William Orbit on remix/rhythm detail – one may survey the latter’s use of space on “Rhythm Of Life” and see Ray Of Light coming quite a long way off), and various UK big-sounding pop reliables (Tessa Niles, Carol Kenyon, Guy Barker, Luis Jardim and an uncredited Anne Dudley all pop up along the way, as do others) present. This was clearly a record meant to be played through the speakers of in-car (BMW?) stereos.

Yet a message at some variance to the opulent smoothness of its surroundings is being conveyed by Adams. The chords of “Rhythm Of Life” are slightly solemn, as though guiltily eloping from church by the back door, but the declarations of “Give the girl a future” and “Maybe she’ll have better luck than me” are abundant and clear. The title song bears an agreeable bounce – the contented hippopotamus of a baritone saxophone is played by Will Gregory, later one-half of Goldfrapp – and, again, the phrase “I needed a soft place to go” – is that not what Ducks Newburyport is in large part about? – breaks through. The song’s hall-of-mirrors multitracked, multi-echoed vocal climax is akin to Rita Hayworth disappearing through the shards of The Lady From Shanghai.

The record’s subsequent sequence of three consecutive songs demanding things, also known as basic human respect – “You’ve Got To Give Me Room,” “I’ve Got To Sing My Song,” “I’ve Got A Right” – strongly suggests that Adams’ milieu is a politely militant one. The first-named of these, performed by Adams with only Guy Barker’s discreet flügelhorn in support, is a patient but pained request by the partner of someone unnamed for freedom. “The walls are closing in,” Adams sings. “Those yesteryears are gone” (Margaret Attwood’s recently-published 2017 poem Dearly springs very strongly to mind in terms of the latter). “I AM MORE THAN WIFE…I am woman,” she declaims, then whispers. The presence of the coda of “Before these precious years are through” suggests that even Sinatra might have given this song a meaningful run (you think Frank couldn’t, or wouldn’t? Try his surprisingly convincing reading of “Send In The Clowns”). A chilled kiss of a string synthesiser coda completes the song’s picture. “Sing My Song” stays happily in church, but did its line “Sing the hatred into love” need to wait until now to have relevance? Why, of course it did! “I’ve Got A Right” is a cheery brassy swagger, dominated by the very fine (if, unfortunately, prematurely faded-out) tenor saxophone of Phil Todd (who was Guy Barker’s bandmate in the Mike Westbrook Orchestra line-up which recorded The Cortége back in 1982).

“Will We Ever Learn,” composed by Nicky Holland and Ellen Shipley – Circle Of One was a record, I imagine, purchased almost exclusively by women, and that “almost” is carrying a lot of weight – is terrific and harmonically reminds me a little of Gil Evans’ “La Nevada,” and Adams still makes it say a lot: “I don’t care if we make a million,” she sings, “We’ve just gotta find another way to live.”

As I say – timely only now?

Banquo’s ghosts materialise in the song’s backing voices, and the climactic declaration of “We’ve only got now” indicates that now IS the time to talk about this record.

“Everything Must Change” was a reading of a song composed by Benard Ighner which was by common consent the emotional highlight of Quincy Jones’ 1974 album Body Heat, as sung by the composer, a Houston musician who also worked with Dizzy Gillespie, David Axelrod and others. Covered by many singers – Streisand and Simone among them – and Adams does the song reasonably maximalist justice. Harmonically slightly reminiscent of “My Funny Valentine,” Adams’ pauses leading to or from each “except” are faultless. Anne Dudley’s strings are placed at the back of the mix and never seek to dominate, although their presence is vital, as is the tripartite percussive knockout which ushers in Barker’s flügelhorn, as eloquent as it would proceed to be in XTC’s “The Last Balloon” at the opposite end of this decade. Barker concludes with a strange whinny, like a stalled horse of the apocalypse atop the hill of hope, before the record finishes with a patient and smiling Picardy third.

The light returns to the world and hell is sidelined into its inbuilt impotence.

“Blew his way to Canton, then to Scranton,

Till he landed under the Manhattan Bridge.”

(“The Rhythm Of Life” by Cy Coleman and Dorothy Fields, from the musical Sweet Charity)

“People had no playfulness. They were clumsy, methodical, repetitive creatures, graceless and brutal – and full of exasperating concern.

She would like to show them who really ruled the world.”

(Ellmann, op. cit., p 939)