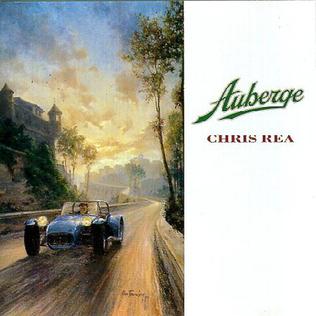

(#424: 9 March 1991, 1 week)

Track listing: Auberge/Gone Fishing/You’re Not A Number/Heaven/Set Me Free/Red Shoes/Sing A Song Of Love To Me/Every Second Counts/Looking For The Summer/And You My Love/The Mention Of Your Name

(Author’s Note: Subsequent CD editions of this album included an additional track, “Winter Song.” This was initially released as a stand-alone single in November 1991 but was eventually incorporated into some future versions of the album, appearing between “Set Me Free” and “Red Shoes.” However, I have based this piece on the original CD release, from which the song is absent.)

“Sometimes I get this crazy dream

That I just take off in my car

But you can travel on ten thousand miles

And still stay where you are”

(Harry Chapin, “W.O.L.D.”)

In deliberate contrast to its predecessor, this record begins with the light sounds of nature and humanity’s compromise with it; birdsong, footsteps, ambient guitar and keyboard flurries, the gentle stirring of a motor engine into action. The song springs into lively action, driven by a bumptious brass band arrangement. What do you do, the singer seems to muse, when your home is collapsing – what can you do, except flee it, retreat to France (where this album was recorded) and drive around randomly yet lucidly?

“Auberge” is the French word for “inn,” and it is refuge which this singer is seeking, above everything and perhaps everybody else. Yet this song “Auberge” is not free of pain or threat. “Think with a dagger,” he muses at one point, “and you’ll die on your knees.” This is evidently not going to be a free-and-easy ride in the exotic countryside, as his pained lead guitar, squiggling for life like an abruptly-marooned pike, makes very evident.

So he decides to go fishing, and is curiously defiant about doing so. He knows nothing about fishing, just as Michael Nesmith knew nothing of Rio, but just watch him go. The world – humanity, life – has let him down; the key quatrain of the whole album is here:

“You can waste a whole lifetime/Trying to be/What you think is expected of you/But you’ll never be free.”

He could have spent his whole life doing this; what was fishing like in his part of the Tees, in the days before rock and roll?

He channels Patrick McGoohan, and possibly also Bob Seger, in the sprightly “You’re Not A Number,” before retracting once more into the semi-abstract fantasy of “Heaven” where, for perhaps the only time on this record, he is happy, has found his real purpose in life. Or so he would wish us to think: “Holding on to this smile/For just as long as I can.”

He does not manage to hold onto it for very long (“When was the last time/You saw a smile?”). “Set Me Free” is the record’s epic cynosure in which he reveals that this “auberge” has only ever been a dream, that he has remained tethered to his hellish road. On the final “And that free, freeway” he collapses the last two syllables into an exhausted sob. Strings and brass arrive, the song escalates in its intensity and the solo guitar screams an urge for…freedom, possibly at any cost. It is most discomfiting listening.

“Red Shoes” treads along like a lucid nightmare reworking of “Let’s Dance,”; the singer appears squashed by Nick Hitchens’ jaunty tuba. He is angry. Give him something. Buy him some red shoes. Give him a reason to continue living. “Sing A Song Of Love To Me” gives way to the inevitable Hank Williams subtext (“warm my cold, cold heart”); here, love is genuinely like oxygen. “Every Second Counts” is reggae-lite hijacked two-thirds of the way through by a solemn, patient interlude for strings. “Looking For The Summer,” the song most people remember from this record; he looks at his daughter and back through his own life, and where was that beach again, the bright and happy future we were all promised? The song affords sufficient spaces in its architecture into which tears may comfortably drop.

But he cannot prevent his demons from reaching and penetrating him. “And You My Love” is unsettling enough to warrant inclusion on a Nick Cave record; he is trying his best to live, but his past, the precise details of which remain unspoken (“Oh, I must have done some wrong/On a dark and distant day”), will not let him be. The melodrama inherent in the song’s melody is unavoidably French; one can imagine a hysterical Johnny Hallyday bellowing it out with scarcely suppressed screams. Yet this singer is about nothing if not suppression, perhaps of his worst instincts.

Finally, he is in that auberge, with just piano and strings to accompany him, and a friend mentions a former love of his, and he collapses inside; he cannot get past the memory of that love, the past which he can no longer reclaim, the final realisation that travelling to another country and attempting to erase or at least minimise all of that pain is useless, because no matter where you go, you take yourself with you, you can’t shake yourself off.

Tell him there’s not a hell.