Track listing: Civil War/14 Years/Yesterdays/Knockin’ On Heaven’s Door/Get In The Ring/Shotgun Blues/Breakdown/Pretty Tied Up (The Perils Of Rock N’ Roll Decadence)/Locomotive (Complicity)/So Fine/Estranged/You Could Be Mine/Don’t Cry (Alt. Lyrics)/My World

“When the world's got you by the fucking throat

Who'd you want in your corner? Axl Rose!

No one understands me, or even comes close

Who've I got in my corner? Axl Rose!”

(Art Brut, “Axl Rose,” from their 2011 album Brilliant Tragic)

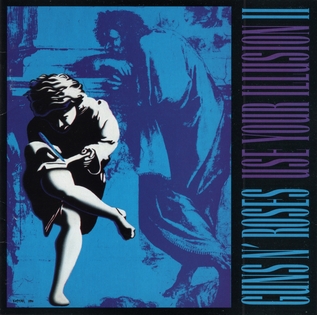

Rock ‘n’ roll. What to do with it, eh? Well, here were some suggestions as to what could be done with, or for, or to it; an epic which the music had rarely seen, and even that was only half the story. There was, of course, a Use Your Illusion I, which wasn’t quite as popular as its companion volume, and since I am not being paid to spend two-and-a-half hours of my life analysing both, I will deal with the key songs there, as well as those from Appetite For Destruction and elsewhere, when I get to entry #715 (it seems so far away in the distance, that number, doesn’t it?).

My feeling is that Illusion II was simultaneously the profounder and the shallower of the pair, and overall the more striking album. Had anybody attempted the simultaneous release of two long-form albums (not counting live efforts such as Gary Numan’s Living Ornaments)? The only precedent of which I can think is Marching Song by the Mike Westbrook Concert Band, which Deram crossly released in 1969 as two separate volumes (because Decca “didn’t do” jazz double albums; nevertheless, all subsequent UK CD reissues of the work have incorporated both volumes as a whole). This is not as farfetched a comparison as it might seem, since Marching Song and Illusion share a common factor – both were engineered by Bill Price (who was brought in, probably on account of his work on a previous number one album, after Bob Clearmountain was fired after he was found to be plotting to replace Matt Sorum’s drumming with samples). There is an emotional directness with both pairs of albums which is rather uncommon.

But Use Your Illusion was an intrinsically uncommon event. It did not receive the best of reviews at the time. Mary Anne Hobbs at the NME was obliged to listen to the whole thing overnight and then write it up, and her review was understandably bad-tempered. There was general talk of pretension and indulgence from a media which preferred their rock to be a matey, face-licking cup of tea (Kingmaker, the Wonder Stuff). Yet for most people, rock IS about indulgence and pretension (how else do, or can, you sum up Ziggy Stardust?), not about buttoned-up behavioural centrism. It should be colourful and vulgar, reckless and unapologetic.

This is a characteristically long-winded way of getting to the point, namely that Use Your Illusion II is one of the very best rock ‘n’ roll albums I have ever heard. Yes, GN’R are unabashed romantics, set against the sober classicism of Metallica. Colour versus monochrome, and both have their places. But listening to these nearly seventy-six minutes of music, one realises how the band in general and Axl Rose in particular spoke to otherwise alienated people.

It is true that much of Guns N’ Roses’ appeal lay in their daring to say the unsayable and yet also be able to empathise with their audience on a very deep level. This album is messy and rigorous, puerile and aged, monomaniacal and expansive. Its first song, “Civil War,” might be their best work; an extended political protest which sadly has not dated a jot in the nearly thirty years since it was conceived and recorded (“We got the wall in D.C. to remind us all”). It is also their last song to feature their original drummer, Steven Adler; dismissed from the band for his heroin habit (producer Mike Clink, with Price, had to piece together Adler’s drum track from some 25-30 separate takes, so untogether was the drummer). Nobody could listen to this and imagine Axl Rose was a far-Right douchebag. This is the band and singer’s declaration of principles which informs the rest of the record.

Illusion II is eminently listenable (even if much of its subject matter is to do with Izzy Stradlin’s messy love life of the time). “14 Years,” written and sung by Stradlin over a piano riff reminiscent of INXS’ “Mystify,” is remarkably febrile. “Yesterdays” is a snarl of a lighters-in-the-air power ballad which was probably even beyond Bon Jovi by this point; Rose makes it clear that he wants nothing to do with nostalgia (“I ain't got time to reminisce old novelties”). And it is played with a confidence and certainty which are frighteningly euphoric. They know that this is going to be a great record.

I love how “Knockin’ On Heaven’s Door” is played as a bar band barnstormer, converting the original’s fatal resignation into life-affirming defiance. The anti-media songs “Get In The Ring” and “Shotgun Blues” are funny, infuriated and musically absolutely compelling (they seem to carry a lot more weight than similar efforts by the Pistols managed). On “Shotgun Blues” we are very firmly reminded, vocally, of Alice Cooper (who himself guests on Illusion I). Both songs bear an enormous power and remind even a sceptic such as myself how completely bloody great rock ‘n’ roll can be when it’s done with this level of chutzpah, guts and mischief.

“Breakdown” is a striking setpiece which methodically and expertly builds up over its seven or so minutes from an initial country ballad mood (complete with banjo plucking from Slash) towards purposive and demonstrative heavy rock with some powerful speech samples (“Let me hear it now”) and climaxing in Rose declaiming Cleavon Little’s key speech from Vanishing Point (“The last beautiful free soul on this planet”). It makes Primal Scream’s similar attempts at damaged rock balladry sound – well, half-baked.

Set against that, of course, are the playpen sexual politics of “Pretty Tied Up” (which does seem fully aware of its innate absurdity), although it rocks pretty powerfully (with a sitar, even!), culminating in a freeform pile-up of guitar effects. Whereas “Locomotive” is phenomenal because it seems, three years ahead of schedule, to predicate Oasis; Rose’s largely drawled vocal is pure Liam Gallagher (yes, I know that should read vice versa) and overall the track gives the pleasing impression that this is their attempt at baggy indie-dance; it certainly sends the likes of My Jealous God packing, and probably pissed off those other Roses from Manchester, at the time ensnared in legal wranglings and unable to record.

“So Fine,” written and sung (or wearily groaned) by Duff McKagan, is a very touching (and indeed stoned, to say the least) tribute to the then-recently departed Johnny Thunders (although Illusion II in general makes the New York Dolls sound mono in comparison) – the final quote on the sleeve was from Stiv Bators, who prematurely left this world in June 1990; the air was thick with rock ghosts. “Estranged” was obviously designed as the equivalent to its companion’s “November Rain” – the epic rock ballad – yet its geometry and use of distance are, as Lena pointed out, reminiscent of none less than late-eighties Simple Minds; there is a very similar elegance at work, and when the rock does finally break free at the song’s climax it provides a very satisfactory moment of emotional release and deliverance.

“You Could Be Mine,” music from Terminator II and acknowledgements to Bernie Taupin and Elton John (“We’ve seen that movie too”), is ridiculously phenomenal rock (musically if not lyrically) which makes most other contemporary rock – that word “most” is doing an awful lot of work here – sound as though it is merely playing, which was doubtless its, and the band’s, intention. One can tell from listening to all of this record how and why a group like the Manic Street Preachers chose to be so inspired by it. What is the point of rock if it isn’t to be big, not to mention bold?

“Don’t Cry” appears on both Illusions with the same chorus but different verse lyrics and subtly different musical structures. The words on the second version are bloodier and more forthright than those on the first, although its initial air of anthemic reassurance is stealthily detonated by the final, inhuman extended syllable which suggests the jaws of robot death closing in on existence. For a taste of the afterlife, there is a brief and hilarious (and scary) interlude (or coda) of industrial rap, misfired synapses and all. As a record it is immense and unchallengeable, or at least appeared so. But it turned out not to be even the best rock ‘n’ roll album released in the second half of its month, and its self-built tower was about, through no inherent fault of its own, to be unutterably demolished. Guns N’ Roses did not record meaningfully in this form again, and the world changed. Guess what it was about to do now. Uh?