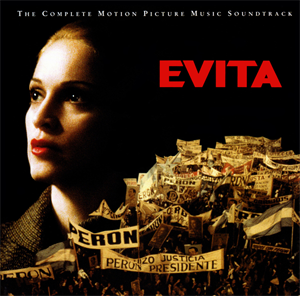

(#562: 1 February 1997, 1 week)

Track listing: A Cinema in Buenos Aires, July 26, 1952/Requiem for Evita/Oh What a Circus/On This Night of a Thousand Stars/Eva and Magaldi-Eva, Beware of the City/Buenos Aires/Another Suitcase in Another Hall/Goodnight and Thank You/The Lady’s Got Potential/Charity Concert-The Art of the Possible/I’d Be Surprisingly Good for You/Hello and Goodbye/Peron’s Latest Flame/A New Argentina/On the Balcony of the Casa Rosata (Part 1)/Don’t Cry for Me Argentina/On the Balcony of the Casa Rosata (Part 2)/High Flying, Adored/Rainbow High/Rainbow Tour/The Actress Hasn’t Learned the Lines (You’d Like to Hear)/And the Money Kept Rolling In (and Out)/Partido Feminista/She Is a Diamond/Santa Evita/Waltz for Eva and Che/Your Little Body’s Slowly Breaking Down/You Must Love Me/Eva’s Final Broadcast/Latin Chant/Lament

(Author’s Note: This review is based on the complete two-CD soundtrack recording; a single-disc seventy-seven-minute-long compilation of highlights was released as Evita: Music From The Motion Picture)

It would have been about 8:35 on the evening of Thursday 13 September 1973 when Tim Rice, driving to a dinner party for which he was already late, switched on his car radio to hear the last ten minutes or so of the fifth episode of a six-part documentary series on BBC Radio 4 entitled The Spellbinders.

This episode, which was written by Gillian Freeman, perhaps best remembered as the author of the 1961 gay biker novel The Leather Boys (which she published under the pseudonym of Eliot George; the novel was filmed three years later, and the movie is directly referenced in at least three songs by The Smiths), concerned Eva Peron, a name hitherto largely unknown to Rice, except that he remembered her appearing on a stamp – as a boy his principal hobby was stamp collecting.

The other five episodes of what the Radio Times billed as “Six studies in 20th-century magnetism” focused on Aimee Semple McPherson, David Lloyd George, Malcolm X, Dr Goebbels – and James Dean, whose 1955 passing Rice recalled from the period he spent in Japan at the time. As that list of names may suggest, there are two sides to the magnetism coin, good and evil. Who falls under which category is largely a subjective decision.

Yet Rice was stimulated by the story of another larger-than-life figure who died too early sufficiently to take the idea of a musical about Eva Peron further. He proposed the idea to Andrew Lloyd Webber as a possible follow-up to Jesus Christ Superstar. But Webber was dubious about writing another musical about an icon who died in their early thirties. He demurred and went off to write the musical Jeeves with Alan Ayckbourn. Ironically, Rice and Lloyd Webber had begun composing such a musical, but Rice pulled out because he was worried that his lyrics were nowhere near as witty as the words of Wodehouse. Jeeves premiered in the West End in April 1975 and lasted barely a month; its 1920s dance band arrangements proved unattractive to a mid-seventies audience reared on rock (however, Lloyd Webber and Ayckbourn revisited the idea twenty-one years later, rewriting the show almost entirely under the new name of By Jeeves, and it did eventually become a great success).

A wounded, melancholy Lloyd Webber returned to Rice and agreed to work on the Eva Peron idea. As with Jesus Christ Superstar, the pair decided to road-test the show as a double concept album in order to see whether anybody might be interested in staging it. Rice in particular had already done some preparatory research; he travelled to Argentina and interviewed various interested parties – many of Eva’s contemporaries were still alive and well in 1974, and he had to conduct pretty much all of that research under careful cover – as well as watching, on at least twenty separate occasions and by arrangement with the director, Carlos Pasini Hansen’s 1972 ITV documentary film Queen Of Hearts, narrated by Diana Rigg, which laid out the broad lines for the musical’s characterisation of Eva – not a huge amount of time was spent analysing the political undertow of Peronism; the film seemed more interested in Eva as a quasi-saintly phenomenon (a pre-Diana Diana?). So impressed was Rice by Eva’s story that he even named his first daughter after her.

What Rice says he did not do, at the time, was read Mary Main’s The Woman with the Whip, a profoundly unsympathetic and perhaps biased and incomplete portrait of Eva. What he almost certainly read was a 1969 collection of essays by the historian Richard Bourne under the umbrella title of Political Leaders of Latin America. I know this work well because my father borrowed it at the time from Motherwell Library. The subjects of Bourne’s studies included both Eva Peron and fellow Argentinian Che Guevara.

Rice was tickled by the thought of getting two icons into one show – even though the original character of “Che” is only Guevara by implication, and did not explicitly become Che Guevara until Harold Prince insisted that he do so. Much like Judas in Superstar, he is a rather cynical narrator who remains present for virtually the whole musical to offer his contrary observations on Eva’s rise and fall. Like Superstar, Lloyd Webber and Rice originally wanted their Judas, Murray Head, to take the role, but a few demos convinced them that maybe he wasn’t going to repeat the magic. Instead they turned to the performer then currently playing Judas in the West End, one C.T. Wilkinson – who subsequently became a huge musical star (and a Canadian) as Colm Wilkinson – and knew he was the Che they really wanted. He does an excellently gruff job, by the way, his voice midway between Rod Stewart and Phil Minton.

For Eva, they had been impressed by the television series Rock Follies, and persuaded one of its stars, Julie Covington, to portray the role on record (they also hired a few of the Rock Follies backing band as musicians, including Ray Russell, Tony Stevens and Peter van Hooke). Paul Jones, one of several sixties Britpop idols to appear on the album, agreed to play Juan Peron. For the role of the tango singer Agustin Magaldi who, in the show, if possibly not in real life, took the young Eva under his wing and to Buenos Aires, Lloyd Webber travelled one evening to the cabaret nightspot Bunny’s Place in Cleethorpes to witness Tony Christie in concert; although his first run of hits had mostly dried up by 1975, Christie remained a huge and popular live attraction. Impressed by his performance, Lloyd Webber invited Christie to participate.

The recording of the Evita album took place between April and September of 1976. Many distinguished performers took part, including Hank Marvin (who plays a very characteristic guitar solo on “Buenos Aires”), Neil Hubbard and then-Wings guitarist Henry McCullough (both formerly of The Grease Band, the original backing group on the Superstar album) as well as session veteran Joe Moretti on guitars, drummer Barry Morgan and keyboardist Ann Odell of Blue Mink, principal drummer Simon Phillips (then principally a member of the Brian Eno/Phil Manzanera art-rock supergroup 801) and stalwarts Mike Moran on keyboards and David Snell’s rather acidic harp (note its discordance on “Buenos Aires” and “Goodnight and Thank You,” as well as its unmoored interlude three-quarters of the way through “I’d Be Surprisingly Good for You”). There are blink-and-miss-them vocal cameos from the Dave Clark Five’s Mike Smith, Mike d’Abo – who succeeded Paul Jones as Manfred Mann’s lead singer – and a not very recognisable (possibly for contractual reasons?) Roy Wood (not to mention from Rice himself, as one of the stuffy officers on “Rainbow Tour”). One of the backing singers is Stephanie de Sykes.

The double album of Evita was released in November 1976, as was a taster single of Covington’s “Don’t Cry for Me Argentina.” Originally recorded under the none-too-persuasive title of “It’s Only Your Lover Returning,” Rice borrowed a phrase from earlier on in the show, and it sounded infinitely more convincing.

Even if Eva’s job on that song is only to convince her audience that spurious bullshit is true. Here is an edited and frankly reworked version of what I wrote about Covington’s single on the Popular website back in May 2008. You can, however, imagine it as coming from a never-to-be-written book entitled Was Michael Powell Right?: High Tory Principles As Applied To Art.

For a pair of writers who were at the time Conservative (with a capital C) in both background and instinct, you could easily mistake Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice for a couple of severely disillusioned Marxists. Jesus Christ Superstar seems for most of its duration to be an unyielding attack on unregulated capitalism and the imperialism to which it gives deliberate birth, as well as the occupational hazard of the destruction of visionaries which is one of its most characteristic by-products.

But Lloyd Webber and Rice were primarily fascinated with the spectacle (are we proceeding down the equally inevitable road to Roland Barthes here?) and consequences of how people and things looked. Looks and appearances, and the judgements made on their primary basis, are the backbone of their fascination; the conjecture that the fate of the world can turn on the hue of Joseph’s coat, or the wiriness of Christ’s hands, or the hips of Eva Peron; what these are all trying to project, even if they’re projecting nothing. Perhaps this is to where humanity descends, in the end; the strength of belief and faith being entirely dependent upon how good a spiel their would-be saviour can weave. If the message is bright and loud enough, believers will gladly overlook the lack of actual content, the fatal avoidance of commitment, the shades behind the smile. As has recently been demonstrated (I have added and italicised that final sentence now).

Evita is an examination of a bright, possibly naïve and certainly corrupted mind; it doesn’t bother itself overmuch with the inherent corruption in post-war Argentinian politics, and how the subsequent bloody military history of Argentina fit in so astutely with the irony that the individual primarily responsible for dismantling their junta roundabout, via the Falklands war, was Margaret Thatcher (who as Leader of the Opposition in mid-1978 was profoundly impressed by the West End production of Evita, which may have helped to inspire her subsequent perspective on things). The whole musical might represent a dream in which “Eva Peron” is only an imagined existence – yet that existence was real, and its side-effects reverberated for decades as a result.

“Don’t Cry For Me, Argentina” is a request, or possibly a plea, for redemption in the resentful eyes of the people out of whom she rose; she has done too many bad things, turned too many backs, is centimetres away from tossing them fragments of semi-swallowed cake. But its pleading is the special kind reserved for the dock; not a genuine cry to be touched, but the cornered, faintly embarrassed confession of someone who’s been caught in the act. Or possibly her big chance to win the gullible fuckers over.

Fittingly, the music doesn’t have much to do with Argentina, apart from a very subtle tango rhythm; the song begins with a solemn tabula of low and very English strings, as though Elgar or Delius had been commissioned to write yet another commemoration of the prematurely departed. Then the voice of Julie Covington enters; hesitant, unstable, she whimpers: “It won’t be easy/You’ll think it strange…/That I still need your love after all that I’ve done.” Then, a pause for breath: “You won’t believe me.” The voice is an ideal one; Covington had floated unobtrusively between the worlds of theatre and folk-pop for some years (see for instance 1971’s “My Silks And Fine Arrays”); it is a voice which knows both how to act and how to believe.

Brass takes over from strings in the second verse as Covington slowly attempts to assert herself: “I had to let it happen/I had to change,” then, with a sense of real anger slowly radiating into her tone, “Couldn’t stay all my life down at heel.” She immediately tries to excuse that incipient rage: “But nothing impressed me at all/I never expected it to,” and she sounds nowhere near convincing or convinced.

Strings return for the chorus: “Don’t cry for me, Argentina/The truth is I never left you.” But what is the nature of that crying – is it mourning for a lost princess, or the baying of a disgruntled mob, crying for her blood? “I kept my promise,” she sings, again on the defensive, before lowering her voice to something like a threat, “Don’t keep your distance.”

In the third verse, acoustic guitar and rhythm enter, together with a pan-pipe synthesiser, providing a direct link to post-Fairport Convention modes, she continues to justify herself (-love?): “And as for fortune, and as for fame/I never invited them in.” Later her voice softens again, “They’re not the solutions they promised to be/The answer was here all the time…I love you…and hope you love me.” It is among the least believable “I love you”s in all of pop. The music stops, like a curtain silently sweeping open to reveal the bloodied mouths and the gallows beneath the balcony – I think of Scott Walker’s concept of Clara Petucci, of the terrified sparrow trapped in the room; the difference being that Eva has walked straight into it, voluntarily and ecstatically (and the general tenor of the orchestration, for example the ‘celli and basses as rhythm at the end of each chorus, suggests that Webber was more than somewhat familiar with Walker’s late ‘60s work).

Over a drone Covington makes her central titular plea, as though her life will depend upon the outside response – as proved to be the case. There is another brief and rhetorical but seemingly eternal pause, before a chorus, evidently dreaming of Gerontius once again (think of the reinstatement of Elgar as revolutionary as proposed in Alan Clarke’s 1975 TV film Penda’s Fen), hums wordlessly, like a deliberating jury (actually, I say to my 2008 self, this is not what happens – Eva appears to falter, unable to complete her address, so the masses take up the song on her behalf, helping her along, rendering her more powerful). Finally orchestra and rhythm join to frame Covington’s concluding chorus.

Then the music glides to a complete halt, and Covington, now seeming for the first time genuinely distressed, whispers: “Have I said too much? There’s nothing more I can think of to say to you,” and is answered by trilling, descending flutes which sound less Latin American, more Le Sacre du Printemps…and then she turns to her jury, to her people, to us, and intones with careful slowness and gravity: “But all you have to do is look at me to know that every word is true.” The syllables of each of these last four words she stretches out over one bar line apiece; the tympani strikes a roll and she is left to ponder her fate.

Or is she? As the orchestra plays the melody fortissimo, now reminiscent (or so my father thought) of Aaron Copland’s setting of Streets Of Laredo, there is suddenly a terrible sense of emptiness and not a small degree of numb shock as we realise that Eva has been addressing nobody, no one at all, even though she is pretending to address what might have been tens of thousands beneath the Casa Rosata; the mental camera cuts to the dressing table mirror and she has been rehearsing the whole thing. As with Peter Sellers’ “Party Political Speech,” we gradually understand in retrospect that all Evita has been doing for the last five-and-a-half minutes – the era of the long single hadn’t quite died away with “Bohemian Rhapsody,” after all – is sweetly and grandly saying nothing at all, save a string of crowd-pleasing clichés which in truth promise and pledge not an atom of what remains of her soul.

The song and record end, on the single, with the orchestra on a question mark of an unresolved chord, as is only right, and its full meaning can only be grasped by listening to it in tandem with its sister song, “Oh What a Circus,” a long hiss of post-mortem cynicism allotted to Che Guevara (played in the West End by David Essex) set to the same tune but at twice the speed and intensity (converted into a 1968 orchestral maximalist pop song by producer Mike Batt, perhaps with the arrangement of the Kursaal Flyers’ 1976 hit “Little Does She Know” still fresh in his mind) it was a top three single in the summer of 1978). But “Don’t Cry For Me, Argentina” has endured as one of the greatest exposés of bullshit masquerading as emotion in all of pop; the song itself is sad enough to make you cry, and then you check yourself – at what, or whom, are you crying, and why? How much “reality” do you actually desire to derive from a piece of music; and, to extend the argument into the fuller world, look – that is, look – at those recent speeches in the United States of America that we already know only too well, and in most cases are now ducking to avoid, and examine the minute slivers of genuine meaning which exist in either, or neither.

That is broadly what I wrote about the single of “Don’t Cry for Me Argentina” sixteen-and-a-half years ago. Yet in the context of its parent album it scares the shit out of one, framed as it is by two semi-spoken setpieces on the Casa Rosata balcony; the newly-anointed Juan Peron assuring us that he is not going to stand for any nonsense, and – far more frighteningly – the shrieking, demotic, ecstatic Eva, marvelling at how fully the crowds have swallowed and digested her sentimental Newspeak, going back out and screaming in dissonant concordance with the masses. Diamanda Galas was never more certain of the Devil than Covington’s Eva is at that, her peak moment of existence.

The 1976 double album of Evita, which managed a week at number one on the NME album chart in February 1977 (but only peaked at number four in the “official” chart), is an extraordinary, if not overly consistent, thing. It is Carlos Pasini Hansen himself whom you hear in the opening cinema dialogue – one of those low-budget and probably dubbed dime store melodramas in which the younger Eva Duarte would have appeared – and this sequence immediately poses the question: what is spectacle, and do we prefer to venerate, commemorate and worship a spectacle rather than, or in place of, a flawed human being? Note that when the celluloid is allowed to run down and the death announcement succeeds it, there is no audience to hand.

The “Requiem” sequence comes as a shock, as was presumably intended; bitonal choruses and booming percussion, a tortuous guitar playing a line we will hear again, in an entirely different context, at show’s end. It’s a bit like the Mahavishnu Orchestra in Goth conference with Britten’s Noye’s Fludde (my school, Uddingston Grammar, staged the latter in the spring of 1976; Britten himself was very ill indeed by November of that year and I imagine was in no fit state to receive or hear Evita). I also discern a subtle Mike Westbrook influence; one of his favourite devices (as used in the opening moments of “View From The Drawbridge” from 1975’s Citadel/Room 315) is for melodies in two entirely contrasting keys to come into accidental contact with each other; the boat sails down the river and we hear a chorus of “Fishers Of Men” as we pass a school.

As this sequence escalates its dissonances and threatens to erupt completely, the cloud suddenly breaks and we have the original “Oh What a Circus” in which Che grumpily introduces himself as the one-man Marxist chorus, standing at the side of the stage, commenting on the action and gesturing to the audience: “can you believe this crap?” On this occasion, however, he is interrupted by a teenage girl who appears to be the reincarnated Eva – or perhaps it’s the actual teenage Eva, taking us back towards the beginning of her story.

Following which her story is duly told, of how she was a bastard, how her father’s “legitimate” family ordered hers to remain out of sight at his funeral, and how desperate and determined she was to escape her lowly chains. She “befriends” Magaldi – there is the hint of blackmail in the chorus’ reference to a questionable affair with another girl, as well as scarcely-suppressed rage at the implication that she may well have been taken advantage of, or much, much worse, in swinging Buenos Aires – Sammi Cammold’s recent New York production of the show makes no bones about the probability of the young Eva having been sexually abused.

Magaldi himself is presented as a faintly ludicrous and slightly sad figure; the initial “On This Night of a Thousand Stars” is delivered to a small and unenthusiastic audience and Che makes catty remarks about how he’s not going to be remembered for his voice. The problem here is that for the character to work, Magaldi really has to be a lousy singer – whereas Tony Christie, if anything, sings the song too well. In fact he sings the song beautifully, like an absolute pro, with subtle nods to the Elvis of “It’s Now Or Never” (but isn’t this supposed to be the thirties?) and by the time he reproduces the ending of the song at the 1944 charity concert where Juan and Eva finally meet (which he never actually did, having died six years previously) the audience (even if recorded) clearly loves him.

But Eva works and most likely screws her way up to the top, as “Goodnight and Thank You” is not shy of reminding us. Once she hooks up with Peron, it’s time for the latter’s former mistress (explicitly a schoolgirl, hmm…) to be sent back to school (of sorts). That mistress is voiced by Barbara Dickson – Rice and Lloyd Webber didn’t think she was quite right for Eva, but did give her one song to sing. “Another Suitcase in Another Hall,” which they thought was going to be the show’s big hit (it did pretty well commercially, but nowhere near as spectacularly as “Don’t Cry for Me”). In it, Dickson, singing in a register too high for her (since she was supposed to be portraying a teenager – she pointedly lowered the key for subsequent live performances), muses with audible pain about what it means for somebody like her to be constantly thrown out of people’s homes and lives, with little optimism or even plain hope about what’s going to become of her. There is a nub of real sadness here which Eva seems intent on avoiding, at least until such time as she can no longer avoid it.

The characterisation of Juan Peron is, I think, an important weak spot. By Rice’s own admission, that character was underwritten, and generally tends to come across as an amiable doofus rather than a ruthless dictator. And Paul Jones is simply too young and happy-sounding to convince as Peron; when first we hear him, he sounds as though he’s strolled in from recording his contribution to Escalator Over The Hill (I wonder how familiar Rice and Lloyd Webber were with Carla Bley and Paul Haines’ masterpiece – an addendum: Jones asked to be involved in Escalator after attending a New York concert given by Charlie Haden’s Liberation Music Orchestra, of which Bley was effectively the co-leader. One of many major setpieces on their self-titled 1970 debut album was a reading of Haden’s “Song For Che”). He does his not inconsiderable best, but we can never quite believe him, enter into his version of the world.

Evita’s first half climaxes in and concludes with “A New Argentina”; this should be a political prophecy as frightening as Cabaret’s “Tomorrow Belongs To Me” but is regularly diverted by Peron’s yes but/no but vacillations, Eva’s furious rebuttals and that dentist’s drill rollercoaster of a fuzz guitar line, as well as Eva briefly taking over Che’s intermittent Basil Exposition plot-explaining function to give a potted history of Peron’s arrest and imprisonment, the public uprising and his subsequent release and political triumph. Covington sings with searing and at times screaming commitment – yes, she really believes this is for the best, even though everybody else can see exactly where it’s all heading.

The show’s second half begins with the balcony-framed “Don’t Cry for Me” but we have already been alerted of Eva’s, shall I say, superficiality when it comes to human affairs, be it instant poverty remedies or loving other people. The first act’s attempt at a love song, “I’d Be Surprisingly Good For You” (actually a song good enough for Linda Lewis and ACT to cover subsequently), sounds stiffly slick, like a seventies television commercial (which again I think was the intention). In “High Flying, Adored,” a very pleasing love song if you don’t listen to the words, Che observes how high Eva has risen and how far down she’ll have to fall.

Act two of Evita isn’t quite as consistent as its first half; there are several longeurs – “Rainbow High” is a wonderful demonstration of shallow commitment (“so Christian Dior me”; of course the Pet Shop Boys were listening and taking notes) and a firm test of vocal registers and octaves for any singer wanting to tackle the role. However, “Rainbow Tour” is a disappointingly prosaic chat about Eva’s doomed pan-European visits, with most of those countries not exactly keen on having another Mussolini, thank you very much. In addition, Eva’s enthusiasm for the enterprise is seen to diminish markedly – indicating a far, far deeper problem.

The show goes on to look at what Eva did and didn’t, or wouldn’t, do. Peronism was a confused political grab-bag into which the worst elements of fascism and communism were deposited and shaken about. Eva seems to have thought it was enough for her simply to be seen, “doing things,” even if the Argentinian economy has to be crashed, seemingly beyond repair, in order to pay for them. “And the Money Kept Rolling In” is a moderate rabble-rouser – imagine the Leonard Bernstein of West Side Story doing “Proud Mary” – where Che, with moderate fury, describes how some of that money seemingly rolls into nowhere and to nobody’s real benefit (except, perhaps, the Perons) and that the enterprise was decidedly shaky, but hey, who cares when you have someone who is a Spiritual Symbol of Doing Things?

Throughout most of Evita we hear a grumpy chorus of stuffed-shirt upper-class types who don’t seem to like any music after The Mikado – and you can palpate Covington’s hurt and anger when, early on in the show, she screeches “SCREW THE MIDDLE CLASSES!” She’s doing this only for her beloved shirt-sleeved descamisados.

But the Army are unhappy. Unhappy with what they perceive as a crass guttersnipe clawing her way towards absolute authority. Unhappy with Peron for falling for it (and, indeed, her). Above all they’re unhappy with the economy. No, as much as they loathed Eva, there wasn’t anything they could do about her as long as the people were happy and the economy was booming. But by the early fifties Argentina was nearly broke and their patience was running out.

Peron, in the show, realises this and argues against Eva running for Vice-President (since he knows that this would lead to their immediate overthrow). Moreover, the main reason why she can’t run is because…her own body is letting her down. She is dying of uterine cancer. Very late on in the show, Eva finally realises that, yes, she actually does love Juan – and yet it’s much, much too late. In the meantime – and perhaps it’s the core of Evita – Che and Eva briefly meet for an imaginary waltz (they never met in real life, but Guevara did once write to Eva sardonically asking if she would buy him a jeep, and apparently also conferred with the exiled Juan Peron in the midst of his mid-sixties Bolivian adventures), fail to square their differences, and conclude – in the manner of a cheery Rodgers and Hammerstein stage song which takes the Then Play Long tale back almost to its very beginning – “There is evil, all around, fundamental – the system of government quite incidental.” It might be the musical’s most frightening moment.

So she delivers her final address to the nation, revisiting the closing words of “Don’t Cry for Me,” except, this time, she means them. Ill beyond redemption and drugged, she experiences hallucinations of her previous life before placidly concluding with “Lament” – and suddenly we are back in early seventies Basing Street, and Linda and Richard Thompson performing “The Great Valerio” (“I’m your friend until you use me/And then be sure I won’t be there”). She sings of the children she will never have – and I note that her own mother was given the same diagnosis. Eva was apparently told that to survive she’d need a hysterectomy…but the Spiritual Mother could not be seen as unable to bear children, so she declined, and so she declined. The fashionistas of “Rainbow High,” now undertakers and pallbearers, will endeavour to preserve her body familiar. The show ends as quietly as any musical had done since…West Side Story.

The 1976 Evita is a forbidding affair. Nobody really comes out of it in a rosy light. Certainly not Che, who demonstrates that he can be a complete c*nt when he wants to, including making fun of Eva’s dying, and certainly not Eva, so consumed by her own image she hadn’t realised that she had eaten herself – I’ve heard the stories about her final, grotesque days, how she was propped up in a standing position in a literal cage, how she may have been lobotomised at her husband’s request, and so on and so gruesomely forth.

The impression appears to be that Rice fundamentally approved of Eva – a poor girl arising from the dirt to make life better for as many people as possible – and less so of Guevara, an upper-class medical student of distinguished ancestry who, it is implied, only went into Marxism because he couldn’t cut it as a capitalist (possibly Evita’s most purposely embarrassing moments come when Che plugs his insecticide; in one such moment, he interrupts Eva’s soliloquy in the manner of a random YouTube or Spotify advertisement). Whereas Lloyd Webber seems not to have liked Eva at all, and Covington pointedly declined to reprise the role on stage because she found that she could not summon one atom of sympathy for her.

Hence, when Harold Prince agreed to mount a stage musical of Evita – Rice and Lloyd Webber had sent him a copy of the 1976 album to see whether he might think a stage show feasible; Prince commented that any musical that starts with a funeral can’t be bad – they needed a new Eva for the West End. Out of thousands of applicants the pair picked Elaine Paige, a singer I’d previously only known for appearing on an early-evening BBC1 middle-of-the-road singalong medley series called One More Time! (other regulars included Scotsman Danny Street, session pros like Paul Curtis and Jane Marlowe, and, in later series, a young Hazell Dean) and who at the time of Evita was fed up with session singing and not having much money and was on the point of retraining as a nursery nurse. However, her agent at the time recommended that she go out and buy the Evita album because, in her (agent's) opinion, she was cut out to play Eva.

Paige did go out and buy the album, played it over and over and learned it by heart…and after eight exhausting auditions she got the part (almost uniquely among the applicants, she made a point of not singing “Don’t Cry for Me” as a party piece). Although she still only had second billing to David Essex (who was, admittedly, a very big star at the time) as Che, she won the audience over from opening night onward.

I am not sure how much of that power is evident on the album of the West End production of Evita which came out in 1978. Irritatingly for awkward historians such as myself, only an album of highlights, as opposed to a complete performance, seems to have been recorded. Essex is far and away the best Che – angry, truculent, self-loathing when he needs to be – and it is he who turns the final “Lament” against itself and adds the sinister spoken coda that, following the military takeover, Eva’s body disappeared for seventeen years. Curtain falls on what was, at Prince’s insistence, a sparse, minimalist set.

But it’s difficult to discern the impact that the production itself must have made – “A New Argentina,” for instance, is cut to a mere two-and-a-bit minutes – and Paige largely sounds reserved and in places a little hesitant, as though holding back her full power, or conserving it for the stage. The unlikely figure of Joss Ackland – the voice of a thousand television commercial voiceovers – as Juan actually works, however; he is, after all, supposed to be old enough to be Eva’s father, and we get a little more of Peron’s lecherous savagery communicated. Siobhán McCarthy’s evicted mistress is convincing, but Mark Ryan’s Magaldi is slightly stiff.

Prince’s production then transferred to Broadway, although Paige could not repeat her triumph as the Actors’ Equity Association insisted that American performers be used. Prince therefore hired two then-largely unknown performers, Patti LuPone and Mandy Patinkin, to play Eva and Che. At the time Patinkin was known only as an actor and had never sung publicly. LuPone found the show a dispiriting ordeal; “Evita was the worst experience of my life,” she told Jesse Green of the New York Times in July 2007. "I was screaming my way through a part that could only have been written by a man who hates women.”

Prince’s chief insistence – apart from getting completely rid of the insecticide subplot – was that the musical’s already rather dated-sounding seventies rock moments (“Dangerous Jade”) be either omitted or modified, a.k.a. their rock elements minimised. He knew that the stage show couldn’t simply be a reproduction of the record, that it had to play more like a “traditional” musical in order to compete with Sondheim et al.

Prior to Broadway, the show had some tryout runs in Los Angeles and San Francisco, and perhaps to Prince’s surprise gained a huge gay following; Eva as an Argentinian Judy Garland. On Broadway, backed by relentless television advertising, Evita ran successfully from September 1979 until June 1983.

A full cast recording of the production was, thankfully, made. Although many who were there and saw the production speak highly of it, I found it as frustrating as Patti LuPone must have done. She does indeed seem to shout her entire role, rather than sing it or unearth concealed emotion. Patinkin sounds like, well, Patinkin, except when he sounds like Meat Loaf when the music speeds up. Bob Gunton’s Peron sounds fine to me. Unfortunately, the late Mark Syers played Magaldi for camp.

Alan Parker had actually spoken with Rice and Lloyd Webber about the possibility of doing a movie of Evita not long after the 1976 album had come out. Robert Stigwood, who had unsuccessfully tried to persuade the pair to write a musical about Peter Pan in 1972, was the producer of the West End production of Evita and, round about 1980, very much wanted Parker to direct the film; having just made Fame, however, Parker was loath to commit to another musical so soon (although he did direct The Wall in 1982).

After that the film rights were up in the air, open to all comers. In 1981 Jon Peters tried to convince Stigwood that he could co-produce a movie of Evita and persuade his then partner Barbra Streisand to star in it; however, Streisand had seen the Broadway production and was deeply unimpressed by what she perceived to be a sympathetic portrait of a fascist. Then, remembering the success they’d had with the film of Tommy, Stigwood hired Ken Russell to direct. Various actresses and singers were auditioned – Russell was keen on getting Liza Minnelli to play Eva (speaking of “an Argentinian Judy Garland”; Russell screen-tested her using blonde wigs and custom-made period gowns) but Stigwood, Rice and Paramount Pictures were insistent that Elaine Paige should do so; Russell was dropped from the project following further disagreements – he had begun rewriting the screenplay without consulting anyone else, recasting the character of Che as a newspaper reporter and staging “Waltz for Eva and Che” in a pair of criss-crossing hospital gurneys (Eva being treated for cancer, Che having just been beaten up by rioters).

Stigwood then approached various other directors, including Herbert Ross (who went off and made Footloose instead), Richard Attenborough (who thought the project impossible), Alan J Pakula and Hector Babenco, without any success. In 1986 Madonna, bringing her into the story six thousand or so words in, came to Stigwood’s office sporting a forties hairdo and period gown to show how good an Eva she would be; she also expressed the preference that Francis Ford Coppola direct.

In 1987, however, Oliver Stone began to express interest in making an Evita movie. Madonna met with both Stone and Lloyd Webber but insisted on rewriting the score and retaining script approval, so Meryl Streep was then approached. Stigwood commented that Streep learned the entire part in one week and as a singer and actress was “sensational” and “staggering.” However, the film’s parent company, Weintraub Entertainment Group, dropped the project after suffering several recent box-office flops. Stone then took the film to Carolco Pictures, but Streep’s demands became more numerous, and although they were agreed to, she dropped out of the project for “personal reasons” (ten days after dropping out, she called Stone’s people to inform them she had changed her mind, but Stone had become fed up and moved on to filming The Doors).

Disney acquired the Evita film rights in 1990 and were set to begin filming, again with Madonna in the lead role. However, plans were cancelled in 1991 when the film looked set to go some five million dollars over-budget. Ownership rights then changed hands again, but in 1994 Stigwood finally managed to persuade Alan Parker – remember him? – to both produce and direct. Parker was determined to ignore Stone’s alterations to the story and ensured that the film would be more solidly based on the original 1976 album; however, Stone protested that much of the script that was used was actually his, and, following a dispute, Parker was legally obliged to share a co-writing credit with him.

Stone had previously met with the then Argentinian president Carlos Menem back in 1988. In 1995 Parker also paid a visit to Argentina to see Menem, who said that, although he had reservations about the project, he would permit filming but not within the Casa Rosata itself, and advised Parker that there were likely to be protests from diehard Peronists, as turned out to be the case.

Antonio Banderas was the first major star to be hired for the film, as Che; indeed, he had been pencilled in to co-star from the Disney days. Parker de-Guevaraised the character and had him assuming more of an everyman observer role; if Evita “was Argentina,” then Che could stand for “the Argentinians.” For the role of Eva, Glenn Close was considered, then Streep again, but Madonna sent Parker a four-page letter explaining why she would be perfect for the part, together with a copy of the video for her “Take a Bow.”

Parker took Madonna on, but on the firm understanding that he, not she, would be in charge. Lloyd Webber was sceptical about her singing ability and insisted that she take formal lessons; these would have a direct effect on her post-Evita work. Rice, however, was adamant that Madonna was the right choice for Eva; he said that he wasn’t looking for “a singer” per se, but rather someone who could sell the songs. Perhaps he realised that Madonna would, in large part, be singing about herself.

Madonna herself travelled to Buenos Aires shortly before starting filming, speaking with those friends, relations and contemporaries of Eva who were at the time still alive. Midway through filming she discovered that she was pregnant with Lourdes. She found the filming experience uniquely intense. Jonathan Pryce was hired to play Juan, Jimmy Nail to play Magaldi.

After the film had been wrapped up, the next job was to record the songs in the studio. Madonna and Banderas were both petrified, Madonna so much so that she found the prospect of singing in front of a large orchestra intimidating; she was used to singing to prerecorded backing tracks. Following a crisis meeting, Parker and Lloyd Webber agreed that she could record her vocal tracks separately and take alternate days off recording. Despite thorough training with vocal coach Joan Lader, all of Madonna’s songs had to be taken down in key in order to accommodate her relatively limited vocal range. Interestingly, the music producer was Nigel Wright – who had also produced Robson & Jerome.

Musically, the soundtrack very much takes its lead from the 1976 original, as Parker had intended; “Dangerous Jade,” excised from all stage productions, reappears as “Peron’s Latest Flame.” “The Lady’s Got Potential” deletes all references to insecticide and capitalism. The musical chairs shuffle of “The Art Of The Possible,” written for the stage, appears as an interlude between “Charity Concert” and “I’d Be Surprisingly Good For You.” Elements of previous manifestations of the show appear in “Partido Feminista” and the children’s choir of “Santa Evita.”

However, a lot of stuff gets lost, possibly to placate the Argentinian authorities so that they could get permission to film on the actual balcony of the Casa Rosata; the “which means” punchlines of “Goodnight and Thank You” are mostly missing, the messy economic mismanagement of “And the Money Kept Rolling In” gets overlooked.

Most problematically, Madonna now gets “Another Suitcase in Another Hall,” and out of sequence – it is now a very long way away from “Hello and Goodbye.” While there is a logic to this – the young Eva seeing her life evaporate in endless quick-change liaisons – it has to be said that the seventeen seconds the then-still unknown Andrea Corr gets, as the actual ejected mistress, at the end of “Hello and Goodbye,” are emotionally cutting and might see directly into a rotting and hollow heart. Then again, might not the mistress be just a mirror reflection of Eva herself (and Madonna singing the song balances out with the harrowing reprise of the chorus that she offers at the end of “Your Little Body’s Slowly Breaking Down”)?

Rice and Lloyd Webber were also asked to come up with a new song in order to straighten out a few loose narrative ends (and also to qualify for an Oscar); “You Must Love Me” sometimes sounds like an instruction but Madonna generally makes it clear that this really is love and she needs it to be confirmed and reciprocated while she is still capable of receiving it - although the song was subsequently, and far more convincingly, recorded by...Elaine Paige. However, Madonna does a good Julie Andrews on the excitedly morbid “Waltz” and surprisingly negotiates the low lines of “star quality” in “Buenos Aires” and “Rainbow High” more securely than other Evas have managed.

Of the other major performers, Banderas’ Che is perhaps misguidedly recast as a Where’s Wally?-type invisible man of the people and retreats to conservatism at picture’s end. Vocally he has the authentic Hispanic accent but he doesn’t cut as deeply or viciously as Essex did. Jimmy Nail I thought an improbable Magaldi – who certainly wouldn’t have indulged in any dalliances with teenagers, but that’s the licence which telling a story buys you – but “On This Night” sounds closer to its tango roots than before, and Nail makes a nice switch-up between his two readings; the first is quavery and uncertain, the second more assured (but isn’t he already a ghost in 1944? Is that one of my hospital nightmares recurring, that second reading – the ghost of Danny Street in the dark, lit up in a packed stadium?). Jonathan Pryce is by some distance the best Juan; he sounds genuinely ominous in the first balcony sequence, yet deeply compassionate when he knows Eva’s life is ending. The arrangements and musicianship are punchily-defined and inventive – Courtney Pine drops by on occasional saxophone, and the lead guitar on “Requiem” is recognisably that of Gary Moore.

As for Madonna? Well, I think she plays the part as though auditioning to play the lead in Evita, much as Eva seemed to be auditioning for the part of Argentina’s “Spiritual Mother.” Her vocal range is fairly narrow, but somehow her emotions become intensified as a consequence – she knows that she needs to concentrate more - and she seems to burrow to Eva’s hollow core pretty accurately (because she, Madonna, knows she might be Eva’s reincarnation?); on the closing “Lament” she is as wrecked as the Kristin Hersh of “Delicate Cutters.” She sounds angry when she needs to be angry. The calling card of “Buenos Aires” could have gone on her first album. I’ll get back to her “Don’t Cry for Me” shortly.

But what does all, or any of this, tell me about Eva Peron and the cult that has grown up around her? Before Evita, few non-Argentinians knew who she was, whereas every Argentinian, for better or (usually) worse, did. I have listened to, watched and read so much, including Tomás Eloy Martínez’s supernatural thriller Santa Evita…and still I am no closer to understanding what is supposed to be so great and worldly (as in world-consuming) about her.

Perhaps it is to do with Trump having killed harmony, happiness and hope a few weeks ago. Despite all of my efforts, I have failed to evade the fact that Trump saw the Broadway production of Evita six times – it is apparently his favourite musical - and was moved by it so deeply he thought he could run for office and be another Eva.

Nor can I escape the probability that this show is asking me to sympathise with a figure who facilitated tyranny and rendered it compatible with sainthood. Hence Evita is either lavish and empty, leaning on the love story and soft-pedalling the inconvenient politics, or is a hugely cynical analysis out of which no characters come out well, pinpointing the limbo where far Right meets far Left and each finds and embraces each other in the centre.

It may be an idea to listen to “The Electrician” by the Walker Brothers – a study based in great part on the doings of the Argentine military junta of the mid-seventies - to learn everything that Evita doesn’t, or won’t, tell you (and how great a Juan Peron would the “lemon bloody cola” Scott Walker of Climate Of Hunter have been?). Or to hear Sinéad O’Connor singing “Don’t Cry for Me Argentina” in 1992, as part of what was lazily assumed at the time to be a cover versions vanity project (how many other hit singles are as fearlessly extreme as “Success Has Made A Failure Of Our Home”?), with its backdrop of a lifetime of inflicted pain and inherited grief.

Best of all, go to the glorious “Miami Mix” of “Don’t Cry for Me” where Madonna, free from all singing-lesson and preloaded cultural restrictions, captures absolutely the song’s centre of vapid ecstasy, donating all the emotion she withheld, perhaps on purpose, from the ballad reading (which she had to do, shivering with nerves, in front of Lloyd Webber and was convinced that she had made an absolute mess of it). Then look at our world now, and realise how irrevocably it has been shattered by our deathless deference to the calamitous chimera of “images.”

"I don't know, though, which version I should keep. Why does history have to be a story told by sensible people and not the delirious raving of losers like the Colonel and Cifuentes? If history - as appears to be the case - is just another literary genre, why take away from it the imagination, the foolishness, the indiscretion, the exaggeration, and the defeat that are the raw material without which literature is inconceivable?"

(Tomás Eloy Martínez, translated by Helen Lane, Santa Evita. London: Doubleday, 1997; chapter 6, 'The Enemy Is Lying in Wait")