(#560: 16 November 1996, 1 week; 7 December 1996, 8 weeks; 8 March 1997, 1 week; 22 March 1997, 4 weeks; 17 May 1997, 1 week)

Track listing: Wannabe/Say You'll Be There/2 Become 1/Love Thing/Last Time Lover/Mama/Who Do You Think You Are/Something Kinda Funny/Naked/If U Can't Dance

Bonus tracks (Punctum's Version): Take Me Home/Feed Your Love/One Of These Girls/Bumper To Bumper/Spice Chat 2: "Shall We Say 'Goodbye' Then?"

I was rather put in mind of another cheerfully open-minded musical theorist, John Stevens, the then-recently departed drummer

who from the mid-sixties onward had been responsible for putting together the

Spontaneous Music Ensemble (SME), a purportedly ego-free unit whose members

all worked equally towards a common musical good, regardless of genre or

gender. On two SME pieces – namely 1968’s “Oliv, Part One,” and 1971’s

live 21-piece big band tribute “Let’s Sing For Him (A March For [the then-recently deceased] Albert Ayler)” – Stevens

deploys a chorus of improvised (but directed) female singers. On “Oliv, Part One”

they furnish lengthy sustained drones (together with Trevor Watts' soprano saxophone) as a backdrop for the piece’s main

featured players (Kenny Wheeler and Derek Bailey - pianist Peter Lemer acts as a sort of midpoint between the two settings), while on “Let’s Sing

For Him” they sing the titular chant over and over until they begin to

modify it and improvise within it, finally breaking out into

celebratory/commemorative atonal freeform cackles and screeches.

The five singers who appear on "Let's Sing For Him" are Maggie Nicols and her sister Carolann (the latter reappeared on record several decades later as Caroline Jackman),

Julie Tippetts (the Face of '68 formerly known as Julie Driscoll), Norma Winstone and Pepi Lemer, and if on “Let’s Sing For

Him” especially (in which all five participate) the notion that they

sound as though they are giving birth to the Spice Girls seems

farfetched, it should be noted that the last named of these women, Pepi

Lemer (wife of the abovementioned Peter, who also contributes limpid Fender Rhodes to the swirlingly abstract middle section of "Let's Sing For Him"), went on to become the Spice Girls’ principal vocal tutor,

teaching them many of the techniques which she (in conjunction with

Stevens and Maggie Nicols) had deployed in the SME a generation previously (details of the exercises in question can be located in Stevens' important manual Search And Reflect: A Music Workshop Handbook).

It would appear from the admittedly limited capacities of searching Google that the Spice Girls are

still held in some critical derision; bland, phoney puppets and so forth

and no fifth. This of course has a lot to do with the misogyny which

remains inherent within the British music establishment, the kind which

confines women to either of the dual permitted roles of feisty,

independent rocker or trembling, victimised waif. Hence when girl groups

succeed in pop – in other words, when women have the temerity to

compete with their male peers on equal showbusiness terms, to access the

same level of opportunity – they are routinely denounced. Thus Riot

Grrl’s concept of Girl Power (and subsequent brokering of same into the mainstream by Shampoo, aided and abetted by, of all unlikely pop stars, Lawrence of Felt, Denim etc.) is lauded whereas the Spice Girls’ simple

modification of Girl Power is damned, at least in the blinkered eyes of

those who don’t realise that “Her Jazz” and “Wannabe” – both sung and

largely performed by women, but both co-written and produced by men -

are two sides of the same coin of advancement.

Furthermore, most of the aesthetic concept behind the Spice Girls came from the Spice Girls; Richard Stannard and Matt Rowe wrote and produced most of their music but the words were those of the Spices (and, on a seemingly too obvious parallel note, whither Bacharach and David’s Dionne Warwick, or Shadow Morton’s Shangri-Las, or Spector’s anyone?). Simon Fuller acted as their second would-be ringmaster but, as he quickly found out, he was not an indispensable male glue to the girls’ bonding; as were not the father and son team Bob and Chris Herbert of Heart Management who in 1994 had advertised for singers in the hope of creating a female equivalent to Take That and East 17, or indeed Michelle Stephenson, who made it to the initial five-piece group and may well have been technically their best singer, but either jumped or was pushed, depending on whom you talk to, for reasons of incompatibility and/or family/personal problems.

Seeking a replacement for Stephenson, the Herberts looked to Pepi Lemer, who recommended a girl whom she had recently been tutoring separately and individually, one Emma Bunton. She bonded with the other four immediately. They then sang, danced, rehearsed, rehearsed and rehearsed. The group was initially named Touch; the Herberts' ambition seemed to be to create a British equivalent of TLC (or perhaps a slightly cooler modification of Eternal, whose song "Stay" all four hundred or so applicants had to sing and dance their way through in the initial auditions for the group in March 1994).

From those auditions, Melanie Brown (Mel C), Victoria Adams (as she was then still known), Stephenson and one Melanie Coloma were selected, with eight others, to proceed to a second set of auditions. Melanie Chisholm (Mel C) had been unable to attend that second audition because of tonsilitis, but when Coloma was found wanting, the Herberts called Mel C back anyway after Geri Halliwell had encouraged them to do so.

Ah yes, Geri Halliwell. She had not turned up to the first set of auditions at all and had given various dubious excuses for her absence - yes, oh definitely yes she would have come, wouldn't have missed it for the world, but she had contracted laryngitis or had burned her face in a skiing accident and I'm so SO sorry Chris, please forgive me, please let me audition, pretty please, I'll turn up this time I promise!

Chris Herbert was eventually persuaded to let Geri into the second set of auditions; when she burst through the door, he was so impressed by her cheekiness, campness and confidence that he knew she'd be the perfect fit for the group, even though her singing capacities were, let's say, slightly limited. Not that this bothered anybody in particular - Mel C called her "a self-confessed bullshitter" but in an admiring rather than admonitory tone. Her bullshit fit the disparate cast of characters that the Herberts were intent on assembling. I'll get back to her contributions later.

The group spent a lot of time in the three-bedroom house at Maidenhead which Heart had provided for them and in nearly recording studios, practising and performing songs (as well as perfecting associated dance routines) which were aimed at a very young (under-tens) female audience, none of which appears to have survived, as well as painstakingly learning how to write or co-write songs themselves. One of the latter was entitled "Sugar And Spice," which encouraged the group to change its name from Touch to Spice.

By the end of 1994, Spice were growing uneasy and restless with what Heart Management wanted from them, as opposed to what they, yes, really, really wanted (it's corny, I know). An industry showcase performance was set up in December of that year at Nomis Studios in Sinclair Road, Brook Green, meeting an extremely positive reaction, not least from Richard Stannard, who was in attendance; his songwriting partner Matt Rowe also became subsequently involved.

Encouraged by all of this, Heart Management prepared what would have most likely been a severely binding contract with the group, which, after due discussion with several outside parties (including Victoria Adams' father), they declined to sign. In March 1995 they split from Heart - absconding with the mastertapes of their compositions while doing so - and set about preparing demos with some of the people they'd met at Nomis. Simon Fuller, then of 19 Management, heard and was impressed by the demos and the group were happy to sign a contract with him.

Interest in Spice escalated, and following a bidding war Virgin signed them in July 1995. Fuller then took the group to Los Angeles to meet up and make contact with various important industry figures. Since there was a rapper already using the name "Spice" it was decided to lengthen the group's name to the Spice Girls, in part as a reaction to how they had been sneeringly described by some members of the music business ("oh yeah, those Spice girls, hyuk hyuk").

The group then prepared to record songs for their first album, but their way was blocked by needless and finally rather flimsy obstacles. Nobody seemed to want "Wannabe" as their first single. The industry wanted a straightforward R&B "banger." Much encouraging noise was made about launching the group's career with "Say You'll Be There" instead. But the contract they had signed stipulated that they would have the final say about single releases, and they were insistent that "Wannabe" needed to be a game-changing or possibly even (Britpop/Loaded laddism) game-closing declaration of principle, up there with (or preferably a lot better than) "Anarchy In The U.K." - "I'll tell you what I want, what I really, really want" could be interpreted as a direct, demolishing response to Lydon's "Don't know what I want, but I know how to get it." They knew the song had to matter, needed to represent so much more than what it seemed to offer; Geri referred to it as a "strange family member."

Nor were Smash Hits particularly interested in them at the time, although they cheerfully invaded publishing offices, radio stations and nightclubs, dancing around and shoving the future in the tired faces of jaded employees. The then-editor of Smash Hits seemed marooned in Britpop; her idea of cover stars in 1996 was the Bluetones. However, the editor of the BBC's Top Of The Pops Magazine, Peter Loraine, spotted the wind of change that was about to start blowing - unlike Ms Thornton, he did not stay in his office when the Spice Girls paid a visit to the premises - and realised that the magazine really had to get on their case, and quickly; so much so that Loraine and his team came up with the nicknames - Scary, Sporty, Baby, Ginger and Posh Spice - which stuck with everybody who was sick to death of grey, stony cod-indie and desired the return of primary colours and brightness.

The most obvious point which male critics

(and they are nearly always male) choose to miss is that the Spice

Girls’ intended audience was girls, and that regardless of the mechanics

of their construct, the old adage of what the consumer gets out of the

music and the musicians being the key factor was what vitally mattered;

beyond question they were role models for young girls, growing up and

not quite sure of their place in the world. Note how “Wannabe” places

the emphasis on female friendship over quick male fixes (“If you wanna

be my lover/You gotta get with my friends/Make it last

forever/Friendship never ends” – in other words, the latter comes first)

and the easy sharing out of the lead vocal between four out of the five

girls; Mel C offering authority, Emma innocence, Geri knowingness and

Mel B utterable mischief.

Moreover, the group's image was principally

tailored towards (as in welcoming) girls, if “tailored” is the right term; in conventional

boy perspective terms they were not especially sexy, but neither were

they a robotic construct – there is something deeply marvellous about

their dance routines not quite gelling together (echoes of Bananarama),

their voices not always in perfect pitch (Geri’s “If you really bug me”

for instance), their outfits clashing loudly rather than blending

politely. Like Bananarama, they looked like the product of half an

hour’s frenetic improvising at the dressing table, making do but mending

pop in the process.

In the video for “Wannabe,” which everybody in The Business hated at the time (their original intention was for a glamorous, glossy video to be made in Barcelona), they cavort

through the Midland Hotel in St Pancras with such shameless glee that

they make New Kids On The Block look like the Four Freshmen with

baseball caps that they always basically were – thus they take on the

characteristics of the boy band and outdo them (Mel C’s somersault!) in

one continuous Touch Of Evil-style tracking shot. They look

like the happiest and luckiest girls on the planet, and much of that

radiates through the record itself, from its introductory puffing and

panting up the stairs to be met with a derisory – or conspiratorial? –

roar of laughter before the track itself kicks in with Mel B’s immediate

stranglehold of “I’ll tell you what I want what I really really want,”

the “HA!”s slashing like newly-sharpened kitchen knives before coming

down to land in the warm pool of “Zigazig-ah!” – the latter the greatest

expression invented in pop since “Awopbopaloobopalopbam-boom!” and

(according to Mel C) meaning pretty much the same thing.

All the

elements which make girl groups great, and the greatest pop

Goddess-like, come into audacious play throughout “Wannabe”; the

close-miked harmonies against wah-wah funk guitars recall the Supremes

of “Stoned Love,” the harsh but cuddly consonants revive the

Shangri-Las, the ice cold Coke can bursting open of the drums/piano

relationship reminding us of that forgotten girl group, the Jackson 5

(Motown goes androgynous!), the general sharp bustle descending from the

preparatory examples of Neneh Cherry and Betty Boo (the double entendre

of “We got G like MC who likes it on her…” abruptly cut off by Emma

dreaming about “Easy V”), the “zigazig-ah!” itself and the climactic

“slam your body down and wind it all around” deriving from ska flowing

into reggae and betrothing “Uptown Top Ranking.” Beyond all that,

Stannard and Rowe’s production and arrangement are near-perfect with

lots of teasing touches of punctum; the sly rhythmic segue into the

second verse (“Whatcha think about that?”) the music dropout on the

first line of the second chorus, the spiral staircase of Mel B’s

defining “You gotta, you gotta, you gotta, you gotta” landing on an

emphatic, euphoric “SLAM!,” the final lasciviously descending “Slam your

body down and zigazig-ah.”

It sounded like nothing else on the

airwaves in the summer of ’96, and even then I thought it the greatest

bubblegum debut since “I’m A Believer” (strictly speaking “Last Train To

Clarksville” came first, but the real story, as with this particular

story, begins with “Believer”) as well as the saviour of pop as pop; at a

time when both opposing poles defined by Oasis and Take That were

growing grey and ponderous, “Wannabe” smacks in at an efficient 2:52. It

went to number one everywhere; in Britain it had the year’s longest run

at the top (seven weeks), sold a million and a half copies (in the

year-end sales rankings it came a very narrow second to the Fugees' “Killing Me

Softly”) and made not only veterans believe in pop again, but also

encouraged millions of people to believe in pop – and the wider message

the song conveyed – for the first time. And for those benighted Virgin

Megastore assistants who continue to fail to grasp the story from A to

Zee, it may be worth reprinting the following reminiscence which

originally appeared in a 2003 obituary:

“One of my fondest

memories…was the time spent on another of his madcap ideas. He came up

with a concept called SubRosa, who were to be an all-women band. They

had to be ‘modern, empowered, talented and sexy.’ I thought this was

just a ruse to meet women, which made him laugh hysterically. He would

write all their songs, control their image, write their press hand-outs,

produce the whole thing and generally be the Phil Spector character. We

duly advertised in the Melody Maker, auditioned some girls and chose

the band. Of course, they were very suspicious of this svengali

character and immediately rebelled, having recorded the album, made a

video, and done a performance at the Piper Club in Rome. Five years

later, The Spice Girls became quite successful…”

The

obituarist was Phil Manzanera, and the “svengali character” was Ian

MacDonald. If only he had been aged between 14 and 30 when “Wannabe”

came out; as it was, stiflingly golden rock history stood no chance

against the friendly but firm female insistence upon nowness and fun…and

life.

The difference between "Say You'll Be There" and its predecessor at number one in the British singles chart is roughly the same as the difference between life and death. Coming out of the grey, stolidly worthy gruel of five boys being forced to dress, act and sing like fifty-year-olds and into the shockingly blue 3D colour of five happy girls taking turns to pull faces at the camera in an evidently blazingly hot Mojave Desert and giving themselves daft aliases (Katrina Highkick! Trixie Firecracker! Blazin’ Bad Zula! Enid Blyton remixed by Russ Meyer!) is akin to being pulled out of the grave. Where Boyzone touch the hem of the Bee Gees’ garment and miss their substance entirely, the Spice Girls’ feeling about “retro” is summed up with admirable succinctness in the intro to their second chart topper, one of the first to use the needle-to-the-scratched-groove simulacrum; a fifties cocktail hubbub of voices, electric piano and vibes is rapidly zipped up into a luxuriously squelchy stride through an “Atomic Dog” rhythm, over which the audibly smiling Spices pledge “I’m giving you everything” and actually sound as though they are.

Once again the

writer’s head can only bow in the wonderfully pluralist architecture of

the record; Emma’s confidential purr (swim in the riveting rapids of

her “tell me” in the first verse – is she familiar with Olivia

Newton-John’s old treadmill?) balanced out by Geri’s pitch-imperfect and

wobbly but thoroughly enterprising vocals (and who needs robotic

perfection here when we are celebrating all that is great about

imperfect human beings?).

Alhough the song on its surface is a slightly impatient request to an indecisive would-be lover to make up his mind and commit, it comes across more as a confirmation of renewed female solidarity and mutual trust (“And all that I want from you,” they sing to each other in the chorus, “is a promise you will be there” – and note how the chorus itself admits the existence of doubt and poignancy with the minor key dip in its third and seventh bars).

"Say You''ll Be There" cunningly combines old memes and new – the traditional harmonies of the bridge after the second verse are immediately succeeded by a collective shriek of a rap (led by Mel B) – “Yeah, I want you!” – after which a harmonica solo from Judd Lander (his first number one since “Karma Chameleon” and another touch of arranging genius; a harmonica in the middle of an utterly 1996 pop record!) leads into an even more frantic cheerleading yell of the first two lines of the chorus which wouldn’t have been out of place on a Fuzzbox or Kenickie (or, more pertinently, a Shangri-La’s) record, before all climaxes at the final chorus with the dramatic high entry of Mel C, leading the promise, beseeching the blessing. A brilliant piece of teamwork by the group, in tandem with writers Jonathan Buck and Eliot Kennedy and dance production team Absolute, “Say You’ll Be There” confirmed to all bar the wilfully deaf that New Pop was still at that supposedly late stage continuing to find unexpected ways in which to renew itself.

The release of the "2 Become 1" single was delayed by one week in order to allow the Dunblane charity record "Knockin' On Heaven's Door/Throw These Guns Away" to reach number one just before Christmas 1996. One does shudder at how easily Thomas Hamilton’s face could have fitted onto the cover of the Prodigy's “Firestarter.” Since it was a year when the girls took the lead in pop over the boys, however, there really was no other way to end 1996 than with the group which had restored lightness to both the music and its attendant, or integrated, spectacle.

Again, comparisons with Boyzone cannot be evaded; here was the Spices’ third number one, the third of three completely different and utterly fresh approaches to different facets of the pop song, and their first ballad. Where the Irish boys strove to make their ballads Portentous Yet Epic Statements (look how big ours is, as it might have been), the Spices relax, float and let newness seek its way in like unspoiled rays of nascent yellow.

The video was shot against a blue screen of stop-motion footage filmed in Times Square (the blue screen, and therefore also the video itself, was actually in a studio in London); the girls, huddling in long, colourful coats, drift spectrally in pairs and trios while life blurs at indefinable speeds around them. The song too is not quite anchored; voices, such welcoming voices, swim through its pools of hope. Where Boyzone belch bravado, the Spices persuade; they make no attempt at Soul, Passion or Honesty, rightly believing that if the art and emotion are sufficiently strong then such qualities will be inherent, rather than having to be drawn out with stern Stax pliers – the only deviation from the contours of the song comes with Mel B’s gorgeously selfless trisyllablic hiccup of “one” before the second chorus.

Much of the rest of Spice suggests a standoff; repeated musical attempts to place the band in the Eternal/internationally-successful girl group category – the straightforward Newish Jill Swing of “Love Thing,” the Mary Jane Girls variation of “Last Time Love” – are systematically blockaded and diverted by the girls themselves, as though TLC had now consisted of three Lisa “Left Eye” Lopeses; witness the ambiguous “Ow!” of Mel C which introduces “Love Thing” or the snarky playground yells of “DREAMING” in each chorus of the same song, as though they are singing along to New Kids On The Block at the back of the bus.

More important, however, is the subversion of those compromised musical environments by rebuffing The Man’s attempts to get with any or all of The Girls; in “Love Thing” they make it perfectly clear that the Mr Loverman/macho bloke approach isn’t going to get him anywhere – “I’m not afraid of your love” they repeatedly insist, because their bond matters infinitely more than his pushing or shoving. Geri and Mel B nudge the point home by quoting the final two lines of the song “Sisters,” written by Irving Berlin for the 1954 film White Christmas and sung by Rosemary Clooney and Vera-Ellen – thereby reminding us not only of the girls’ younger days watching seasonal television, but also of their subtle umbilical attachment to the world of British Light Entertainment (which they are absolutely intent on inverting inside out).

The seduction offered – up to a point – in “Last Time Lover” (the song was initially called “First Time Lover” but it was felt that went a little too far carnally) is part genuine, part sardonic, as though the would-be lover is being mocked as gently as he is being guided. Geri’s rap section is performed as though she’s stopping herself from laughing, or yelling. They are intent on him being their last lover, though raise a collective eyebrow at the prospect that Mr Assured Loverman might really be Mr Awkward Newbie (“Could it be your first time, maybe?”).

Of Spice’s remaining songs, “Something Kinda Funny” is fairly routine R&B-lite filler, while the closing “If U Can’t Dance” – the midrange staccato voicings in its choruses put me in mind of ABBA – is entertaining but curiously inconclusive. Into a moneyed desert of abandoned-future samples – The Jimmy Castor Bunch’s “It’s Just Begun” and Digital Underground’s “The Humpty Dance” are recognisable, if the song’s overall feeling has more in common with “Connected” by The Stereo MCs – burst decidedly yet deliciously impolite irruptions; Mel B’s broad Leeds rap (is this suddenly The Three Joans?) and Geri’s snappy Spanish spoken interlude. Indie-dance? The Spice Girls had that market cornered too. As an album closer, however, it leaves several key questions dangling in the spangled air.

One of these questions, and perhaps the profoundest of them, is raised by the song which comes between those two – “Naked,” the Spice Girls’ greatest and most neglected achievement. Unlike any of the record’s other nine songs, and making little fuss of its singularity, the slowly-undulating tripping-hopped undercurrent of “Naked” is the most plaintive pair of eyes to pierce the hollow glamour that listeners might think is otherwise being offered. It sees right through all of your shit.

The song’s main protagonist we can safely take to be Emma, with Geri as her harsh conscience (“She knows exactly what to do with men like you”). She is with an unspecified Him, maybe wanting to do something, more likely trying to avoid doing anything. It is no longer a question of two becoming one but of one striving not to split in half.

Because she harbours a secret, and like the average protagonist of an Eley Williams short story, she’s not about to tell you anything frankly, out loud. To an extent you have to intuit her subconscious, place the pieces together. The other girls wander in and out of the song’s undusted cloisters in the manner of a strolling Greek chorus.

The song’s mood is nocturnal and evanescent, although this is not the peaceful night of “2 Become 1” but rather a restless and possibly ominous one, when you imagine that the clock’s been put back by two hours and it’s always going to be 3 a.m. (Eternal). It bears words about the child being deprived of goodness – though not of strength (“Past encounters have made her strong/Strong enough to carry on…and on”).

At the heart of “Naked” are two voices. One – and it is the album’s single most disturbing moment – is Emma, speaking over the telephone, audibly shattered and exhausted, possibly talking to Him, clumsily trying to apologise for…well, what (“I’d rather be hated than pitied”)? Her voice sounds drained, empty, scared, angry. “Maybe I should have left it to your imagination – I just want to be me.”

Upon which erupts Mel C’s scream of rage, the second of these voices: “THIS ANGEL’S DIRTY FACE IS SOFT!” It is clear that the girl was abused, in some way or another, as a child – see, this is where your rock’s rich tapestry of little girls and sweet sixteens gets them – and is perhaps even being abused right now, but is too confused or frightened to call Him out on it. She wanders in perpetual half-light because the actual light was snatched away from her at a point in her life where darkness was not desired.

The spell which “Naked” casts throws the rest of Spice’s songs into a darker light; in this context you can see why the defiance and cheek are needed, the fun and colour to cancel out or conceal the anger and darkness. You fucked us up as girls, now we’re going to fuck you about as women – that is their central message, their real manifesto. Cutting up your loaded laddism, your pusillanimous guitars, your canon of the permitted, rendering you as lesser beings. It’s been a long time coming. Shuffle along, you redundant grey ghosts of geezers.

But it still doesn’t conclude the album, even though the song sums up its central ethos with stark beauty. I didn’t feel that we could leave things with “If U Can’t Dance” back then and still don’t. I have therefore taken the liberty of preparing a “special edition” of Spice with bonus tracks of my choosing (link to playlist in the track listing at the top).

Firstly, I had to include “Take Me Home,” which at the time was consigned to the B-side of “Say You’ll Be There” but remains one of the Spice Girls’ most remarkable works. Here are the young girls, sitting in a white room and dreaming of a misleading notion of paradise, only and eventually to realise that it isn’t what they want; hence the plaintive echoes of the song’s title in the choruses, accompanied by a snatched alto saxophone lament of a sample. Its further venture into the world of trip-hop is amplified by intermittent gnarled, throaty drawls – you could scarcely term it “rapping” - from Geri which sounds like nothing and no one less than…Tricky!

I could only follow that meditation with “Feed Your Love,” a song excluded from Spice at the time because its dissection of sexual fulfilment was considered perhaps too near the knuckle for an intended audience of sub-teen girls. Perhaps the group also thought it too close, stylistically, to “2 Become 1” and felt that the record needed more “bangers.”

In any event, the song did not appear in public until its inclusion on the 25th Anniversary Deluxe edition of Spice, and it’s a shame (though understandable) that it wasn’t on the original album since it answers many of the questions some of the record’s other songs ask and finds the Spice Girls – happy and fulfilled. It is also maybe their most sheerly beautiful song, five very patient minutes of gradually-unfolding keyboards and beats – a direct descendant of the Art Of Noise’s “Moments In Love” really - which finds its ultimate release in the blissful silence into which the end of the track recedes, like a setting yet satisfied sun (“I really wanna share my secrets with you”).

I felt that it was then time to turn the temperature and rhythm up, so the next song I selected was “One Of These Girls,” a B-side to the single of “2 Become 1” which more or less lays out the template for Xenomania and Girls Aloud, in which the girls merrily flirt with that fourth wall – “Do you think they’ve got it?/Well, I’ve got it!/I’ve always had it/No way; they won’t get it,” “CAN’T YOU SEE WE’RE ALL PLAYIN’ A GAME?” This is a concept of which Kathleen Hanna or Liz Phair would have been mightily proud.

The last song, as such, on “Punctum’s Version” of Spice does not appear on the 25th Anniversary Deluxe edition of the album and indeed has not appeared on any Spice Girls album at all; it has remained the B-side of “Wannabe,” the single which I bought from the Virgin Megastore just as the summer of 1996 commenced.

But “Bumper To Bumper,” perhaps perversely, is one of my favourite uptempo Spice Girls songs and, although the group have obviously viewed it in a dim light, I think it would have furnished a splendid sticking-tongue-out coda to Spice. Written in conjunction with Cathy Dennis – not a name one normally sees in this company – the song is cheeky, saucy and all those other loathsome adjectives which the unthinking application of camp has debased over the last twenty years. The sexual metaphors are unconcealed and the girls are audibly having a lot of fun with the song, voicing the title a dozen different ways before settling for Mel B and Geri’s climactic femipunk screech of “BUMPAH-TOO-BUMPAAAAH!!”

I chose to end my version of the album with a 48-second segment of the girls cheerily and hoarsely saying and yelling goodbye to their fans and listeners, everyone keen to get in the last word, or at any rate the last farewell. The concept works – everything pop does is gonna be female from now on, we’ve taken over from the boys and welcome all of you to our significantly improved world.

Spice is one of the most sheerly welcoming of number one albums since Please Please Me. To me it stands as both a fabulous pop record in itself and an incisive commentary on what we ought to expect from pop music, which isn’t quite what some might have imagined.

And, again and again, I am drawn on this record towards Geri Halliwell and the absolute necessity of her being A Spice Girl. What does she do? It is abundantly clear from listening to both Spice, and the albums which came after it, that she is the group’s agent of punctum. Over and over she disrupts songs, unsettles expectations of how A Girl Group would handle pop, puts a bug into the serene system. Maybe the Phil Manzanera comment at the head of this piece isn’t too far from signifying what Geri represents – as an earnest but flashy, if courtly, “non-musician” whose main function seems to have been to feed ideas and philosophies into the Spice Girls’ music – which is that she is the group’s Brian Eno; and yet, as she also acted as the main focus and de facto leader of the Spice Girls, she also manages to become the group’s Bryan Ferry. I wonder if Ian MacDonald saw that coming.

“BECAUSE we must take over the means of production in order to create our own meanings.

BECAUSE viewing our work as being connected to our girlfriends-politics-real lives is essential if we are gonna figure out how we are doing impacts, reflects, perpetuates, or DISRUPTS the status quo.

BECAUSE we recognize fantasies of Instant Macho Gun Revolution as impractical lies meant to keep us simply dreaming instead of becoming our dreams AND THUS seek to create revolution in our own lives every single day by envisioning and creating alternatives to the bullshit christian capitalist way of doing things.

BECAUSE we are unwilling to let our real and valid anger be diffused and/or turned against us via the internalization of sexism as witnessed in girl/girl jealousism and self defeating girltype behaviors.

BECAUSE I believe with my wholeheartmindbody that girls constitute a revolutionary soul force that can, and will change the world for real.”

(Excerpted from Riot Grrrl Manifesto, BIKINI KILL ZINE 2, 1991)

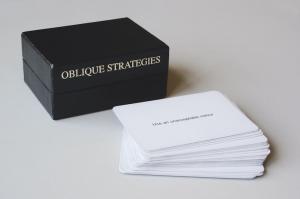

“Assemble some of the elements in a group and treat the group.

Feed the recording back out of the medium.

Listen to the quiet voice.

Not building a wall but making a brick.

Don’t be frightened of clichés.

Think of the radio.

Change nothing and continue with immaculate consistency.

What would your closest friend do?

What wouldn’t you do?”

(Excerpted from Oblique Strategies by Brian Eno and Peter Schmidt, 1975)