Tuesday, 28 September 2010

Neil REID: Neil Reid

(#105: 19 February 1972, 3 weeks)

Track listing: You’re The Cream In My Coffee/On The Sunny Side Of The Street/Peg O’ My Heart/Ye Banks And Braes/Happy Heart/When I’m Sixty Four/Look For The Silver Lining/If I Could Write A Song/When I Take My Sugar To Tea/My Mother’s Eyes/I’m Gonna Knock On Your Door/The Sweetheart Tree/One Little Word Called Love/How Small We Are, How Little We Know/Ten Guitars/Mother Of Mine

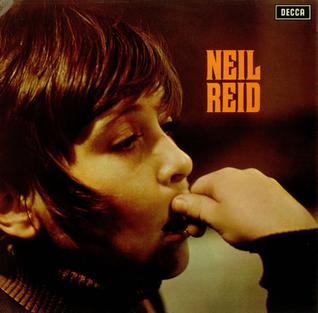

It’s an unusual cover photograph; he is not eagerly grinning at us, as you might expect from a performer of his age, but rather looking away from us, pensive, and with that pronounced upper lip, looking not unlike the younger Gordon Brown. The inevitable question is: what is he thinking? How did I end up here? Am I excited or scared? How long is this thing going to last? I wonder what my mother’s making for tea tonight. What is this West Hampstead, this big recording studio? How far away am I from home, exactly, and will I be able to find it again?

The Motherwell lad, sometimes billed as “Wee Neil Reid,” is still the youngest artist to top the British album chart, at 12 years and 9 months, but the child prodigy factor is only one element at work here. The record is the first augur of one of the key trends to dictate this tale in the future, namely success fuelled, and in many cases created, by the power of television. Throughout the seventies in particular, as we shall see, there were innumerable attempts to deny that this was the seventies, a craving to escape to any other time – the fifties, the sixties, nineteenth-century Vienna, even that abstract spider known as “the future” – than now, and music channelled through television helped to feed that hunger. A glance at the singles charts at the beginning of 1972 gives it away; as well as Neil Reid, we find Benny Hill, Cilla Black and Val Doonican, theme tunes from action series (The Persuaders - John Barry’s artful marriage of medieval cimbalom and future shock Moog remains unrivalled) and soap operas (“Sleepy Shores,” the theme from medical drama Owen M.D., starring Nigel Stock, the man who once pretended to be Number 6 – or was he the real One?), advertising jingles (“I’d Like To Teach The World To Sing”) and even a nod to the big screen (“Theme From Shaft”). Shortly thereafter, thanks to the dubious but unarguable power of Hughie Green’s Opportunity Knocks, Neil Reid’s debut album made it into this story. Why the sudden eruption? It should be remembered, amongst other things, that the period 1971-2 marked the point where colour televisions became affordable, when Grundig, Ferguson and others manufactured sets which anyone could buy.

But it should also be remembered that as 1972 dawned there were only three television channels – BBC1, BBC2 and ITV. The choice was less, external options were fewer, and so viewers had to tune in, essentially, to the same things. Thus audiences of 20-25 million for soaps and variety and comedy shows – then, almost half the population of Britain - were relatively commonplace. A common language was agreed and spoken. Shows such as Opportunity Knocks took full advantage of this; having moved to television from radio in 1966, the weekly you-the-people decide talent contest quickly caught on. Broadly similar in format to today’s Britain’s Got Talent, the avuncular Montreal-born Green presided over a bill of half a dozen or so acts, some singers and musicians, others comedians, yet others what were then known as “specialty acts” – magicians, jugglers, bodybuilders, plate spinners, even singing dogs – out of which viewers had to cast a postal vote on a weekly basis to determine which of these acts would return in the next episode. It was an enticing façade of popular democracy (“I mean that most sincerely, folks – it’s YOUR vote that counts!”) whereby the public could feel as though they were helping to make an ordinary person a star, but of course few of the acts who made it to the show were green, in any sense; nearly all of them had put in time on the club circuit, and Neil Reid was no exception.

The boy was apparently discovered singing at a Christmas party for pensioners in 1968, and over the next few years he appeared on various club bills during his school holidays. Eventually he came to the attention of the Opportunity Knocks producers, appeared on the show, and was a sensation; not since fellow Scotsman Jackie Dennis in the late fifties had a homegrown child star risen to such prominence, and that turned out to be a harbinger in itself (but more of that later). He was signed to Decca, the single (and featured song on the show) “Mother Of Mine” was rush-released at the end of 1971, and quickly climbed to number two (only prevented from topping the chart by the aforementioned Coke dynamo “I’d Like To Teach The World”). The local papers in Lanarkshire adored him, as did mothers and grandmothers everywhere.

An album of sixteen songs was put together by Dick Rowe (the man who a decade previously had turned down the Beatles; the fact that he was also the man who signed the Rolling Stones, the Moody Blues, the Small Faces, the Zombies, Van Morrison’s Them, John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, Tom Jones and Engelbert Humperdinck among others has been conveniently forgotten) and producer/arranger Ivor Raymonde, and unusually a degree of thought and modest adventure appears to have gone into its making. The songs were a mixture of old pre-war and inter-war favourites (for the grannies) and more contemporary material, and never is the selection or approach predictable, even if the approach doesn’t always work.

“You’re The Cream In My Coffee” begins with discrete ukulele and bass plucking, and what immediately strikes the listener is the unalloyed confidence of Neil’s voice – he occasionally misses his target in terms of phrasing and pitching, but the misses are always narrow and there is a latent power in his grain which somehow exceeds the material he’s been given to sing. He negotiates the tightrope trickery of the song’s complex middle eight, composed of successive trapdoors of modulations, very skilfully indeed. Unfortunately the intrusion of the teatime variety choir and vaudeville trombones rather spoils the track’s atmosphere, but the song soon cuts back to its original setting; there is something of a wink in Reid’s quick “You!” signoff.

The arrangement given to “On The Sunny Side Of The Street” is rather bewildering; the song is taken comparatively slowly, and the striptease mood (complete with nightclub bongos) strikes me as less than apt. Again the choir steals in to spoil things, and the North Pier organ solo midway through loads the track with excessive cheese, but the nice lyric change (“I’ll be as rich as Elvis Presley”) is carried off with good humour. Still, there is as yet nothing to suggest anything other than a fairly standard early seventies MoR album, and this feeling doesn’t radically change with “Peg O’ My Heart” – later used, in its original arrangement, as the theme for The Singing Detective - which here is treated in the manner of a Co-Op commercial. The song’s bridge is somewhat scrambled, and there is a bizarre interlude where the strings make a half-hearted attempt at a Highland reel (“Yip!” barks Neil) – wait a minute; is there something else going on here?

His version of the traditional Scots song “Ye Braes And Banks,” however, is a different matter. Raymonde’s arrangement becomes liquid and iridescent, and there is something in the tone of Neil’s voice which now suggests possible futures; the song is taken patiently and rather opaquely, but there are long stretches where, even as a Scot, it is impossible to discern exactly what he is singing – instead, there is an almost alien purity about his voice as an instrument in itself, and I have to remind myself that, not only was Elizabeth Frazer about a year Neil’s senior, but also Ivor Raymonde’s son Simon would eventually become a Cocteau Twin; I wonder if the two boys ever met, and what influences from this Simon would carry over with him a dozen or so years hence. Again, with “Happy Heart,” Neil is stretching out his vowels and consonants in a way I’ve only known one other singer to do – his near contemporary in Dundee, Billy MacKenzie. Now he is really settling into the record, and even essays a bit of scat singing with some success. His “When I’m Sixty Four” involves a children’s choir (and, if the photographs on the rear of the album are anything to go by, Neil himself at the piano); it’s a pleasant little conceit, a knowing in-joke.

But “Look For The Silver Lining,” a Jerome Kern ballad from 1919, provides the record’s most heartstopping moment, and Raymonde’s most creative production and arrangement work; Neil’s voice is pitched as a distant echo, not quite graspable...and then the song, quite unexpectedly, goes “out”; cymbals fade into processed hisses, there are meandering meadows of guitars electric and acoustic (and one of the guitarists is, to cloud matters further, Derek Bailey, not a million miles from his other-galaxy work on Tony Oxley’s “Stone Garden”), rumbling bass and tinkling electric piano, and then the song fades out of focus and even audibility, eventually returning on a crest of Free Design harmonies (“Look for the silver lining, silver lining”); the atmosphere is somewhere between early Boards of Canada, Belbury Poly and Saint Etienne’s “Avenue.” The track not only cries out to be sampled, but also works as a portrait of genuine hauntology; that is, the piece is haunted by the ghosts of the music which will, intentionally or not, follow it. Side one then winds to its agreeable end with Howard Greenfield and Neil Sedaka’s “If I Could Write A Song,” and Neil’s general phrasing here is highly reminiscent of that other former child star, Scott Walker.

“Take My Sugar To Tea” conceptually balances out “Cream In My Coffee” and is similarly arranged, with more ukulele and the occasional blast of trombone (possibly from Paul Rutherford – I am not sure how this album is affected by having two-thirds of Iskra 1903 playing on it), but the arrangement is rather stilted and bumpy (the generous tympani solos do not help) and Neil again sounds a little out of his element. Then again, towards the song’s end, ukulele, electric guitar and tympani engage in a three-way summit of pointillism which hovers delicately atop the border of abstraction. “My Mother’s Eyes” is more successful; Raymonde remembers his Dusty Springfield and Walker Brothers days and lets out the Spector floods in his orchestration (complete with echoing pianos, etc.). Once more, the choir is strictly not needed, but the approach by both arranger and singer is epic, stentorian, rhetorical, and Neil works up to a satisfyingly chilly high note finish.

“I’m Gonna Knock On Your Door,” however, is tackled as neither Eddie Hodges or Little Jimmy Osmond could have imagined it; fuzz guitar and furious Hammond organ lead us, via some handclaps, into a netherworld somewhere between “Hang On Sloopy” and the not-yet-recorded “Children Of The Revolution”; the approach is defiantly bump and grind (but he’s only twelve!) and amidst the thunderstorms of rhythm and descending (into hell?) organ riffs, Neil sounds a bit lost.

However, we then move into a meditative state-of-the-world interlude. “The Sweetheart Tree,” composed by Henry Mancini and Johnny Mercer, was commissioned for Blake Edwards’ movie The Great Race; when I was eight or nine, I thought the latter my favourite film, uproariously funny, and I haven’t revisited it since for fear of disappointment (since it was another in the long post-Around The World In Eighty Days/It’s A Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World series of throwing lots of famous names together and making them have hilarious scrapes in all sorts of different places; I suspect that I would now be bored rigid by Lemmon’s hamming, by Natalie Wood’s blankness, by the overlong Prisoner Of Zenda skit which climaxes the film). It’s an odd choice for a slapstick comedy, but note the guitar (and/or clavichord) work here which gives the number an ethereality which, again, would find its true home with Robin Guthrie and (via Neil’s admirably controlled vocal) Elizabeth Frazer; one almost forgets the return of the kids’ choir. “One Little World Called Love” leads us back to the main 1971-2 milieu, that of where the world is going, that love could still save us all, although note the deadpan guitar comping throughout, and also the occasional breakout of a disturbing shard of lyric (“A peal of thunder when God sounds his gun”). This sequence concludes with the plaintive waltz (but composed by the radical composer Earl Wilson Jr, although this version seems to take its cue from Josef Locke’s 1969 reading) “How Small We Are,” bookended by an astutely solemn brass chorale.

“Ten Guitars” is the Humperdinck standard, and both Neil and Raymonde do their best to make it sound as unlike Engelbert as possible. Flute flutters, drums are busy in a hip-shaking way, but the message persists (“Through the eyes of love, you’ll see a thousand stars”), even as Reid manfully (or boyfully) takes the song out with some exhortations (“Come on everybody!,” “All together now!”).

“Mother Of Mine” itself is left until last. Composed by the guitarist Bill Parkinson (formerly of Screaming Lord Sutch’s backing band the Savages, and an unwitting contributor to the key song on entry #109), the song’s simple poignancy works in its favour and Neil’s performance is faultless, even through the lush choirs and final key change. But there remains something oddly otherworldly about it; it doesn’t really fit into any timespan (is it 1952 or 2022?), and he is singing such lines as “When I was young” when he is still only twelve. And there is, of course, something which moves me about the record which maybe exceeds the record itself; listening to Neil’s singing here (especially his five-note “way”s), I cannot help but think of the fourteen-year-old Billy – a man who would eventually end his own life out of unreachable grief for his mother’s death – and how, or if, he would have sung this; the similarities are unavoidable. And that's not even to mention the record's role as a bookend of premature maternal lament for its decade, the other being Lydon's beyond-articulation howls of grief on "Death Disco."

But Neil’s life continued to a much more successful issue. His initial success was not sustained – a follow-up single, “That’s What I Want To Be,” and follow-up album, Smile, both released later in 1972, both barely scraped into their respective Top 50s. Of course, the Osmonds had arrived in the interim, and suddenly they seemed much hipper, much more in tune with the times; the final irony came when Little Jimmy covered “Mother Of Mine” for the B-side of his Christmas chart-topper “Long Haired Lover From Liverpool.” Neil couldn’t have competed with that, and nor, I suspect, would he have wished to do so. He returned to the clubs for a further year or so and then his voice broke. He continued to record for a time, including with Roy Wood – notably his more than decent 1974 single “Hazel Eyes” – but to little avail, and he moved into the touring musical circuit for a few years before opting out of the music business altogether. Eventually he became a practising Christian, and today he lives happily in Blackpool, works as a management consultant and runs what he calls a progressive, 21st century church named Oasis Blackpool. His initial success did open the floodgates for a host of wannabe child stars, most (but by no means all) of whom similarly came up via the Opportunity Knocks route. Of that flock only Ricky Wilde (as co-producer, co-writer and guitarist for his younger sister Kim) and Bonnie Langford have continued to prosper; other stories are necessarily more tragic or routine. I doubt that there will be much, if any, call for Neil Reid to be upgraded to CD status, but as a modest stew of differing time periods in popular music it does what it set out to achieve, and the astonishing “Look For The Silver Lining” in particular demands rediscovery.