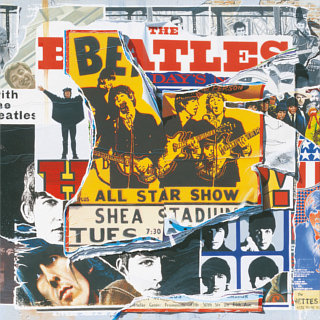

('#545: 30 March 1996, 1 week)

Track listing: Real Love/Yes It Is (Takes 2 & 14)/I'm Down (Take 1)/You've Got To Hide Your Love Away (Takes 1, 2 & 5)/If You've Got Trouble/That Means A Lot (Take 1)/Yesterday (Take 1)/It's Only Love (Takes 3 & 2)/I Feel Fine/Ticket To Ride/Yesterday/Help! (all four songs live on Blackpool Night Out)/Everybody's Trying To Be My Baby (live at Shea Stadium)/Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown) (Take 1)/I'm Looking Through You (Take 1)/12-Bar Original (Take 2, edited)/Tomorrow Never Knows ("Mark 1"/Take 1)/Got To Get You Into My Life (Take 5)/And Your Bird Can Sing (Take 2)/Taxman (Take 11)/Eleanor Rigby (strings only - Take 14)/I'm Only Sleeping (rehearsal)/I'm Only Sleeping (Take 1)/Rock And Roll Music/She's A Woman (both songs live in Tokyo)/Strawberry Fields Forever (demo sequence)/Strawberry Fields Forever (Take 1)/Strawberry Fields Forever (Take 7 and edit piece)/Penny Lane (remix)/A Day In The Life (Takes 1, 2, 6 & orchestra)/Good Morning Good Morning (Take 8)/Only A Northern Song (Takes 3 & 12)/Being For The Benefit Of Mr. Kite! (Takes 1 and 2)/Being For The Benefit Of Mr. Kite! (Take 7)/Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds (Takes 6, 7 & 8)/Within You Without You (instrumental)/Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (Reprise) (Take 5)/You Know My Name (Look Up The Number)/I Am The Walrus (Take 16)/The Fool On The Hill (demo)/Your Mother Should Know (Take 27)/The Fool On The Hill (Take 4)/Hello, Goodbye (Take 16)/Lady Madonna (Takes 3 & 4)/Across The Universe (Take 2)

The inquisitiveness of the archivist has to be balanced out with the cold rationality of circumstances. There was a certain sense of closure about the hitherto firmly-closed catalogue of The Beatles. Despite reams of illegal evidence to the contrary, the Parlophone/Apple vaults were not empty; far from it. And there is a small element of Wizard Of Oz disillusionment inherent in discovering the untidy nuts and bolts which made the finished constructions possible - the great power turns out to be a little, insecure man pulling levers behind a curtain.

The general understanding, however, is that Paul McCartney agreed to the Anthology video and audio opening of the band's archives essentially as a favour to George Harrison, whose Handmade Films company had collapsed in 1991 and who was apparently close to bankruptcy. There is also, of course, as with other posthumous Beatles collections, the beat-the-bootleggers subtext; and, perhaps above everything, there had been Britpop.

The attempted coronation of the partially resurrected Beatles, intended to crown and climax the year of 1995, failed in Britain; mainly because too many other people preferred Michael Jackson preaching about the Earth dying, or Robson & Jerome, perhaps because the silent majority's idea of The Beatles stopped around the time Anthology 2 begins.

Then again, "Free As A Bird" wasn't nearly enough. At the time, however, it felt almost holy. I remember walking up and down Fulham Palace Road one grey Tuesday lunchtime, with Anthology 1 in my Walkman and "Free As A Bird" playing over and over again, as though trying to summon some long-fled spirit. I didn't think of it at the time as a fudged compromise, using a fragment of a lo-fi Lennon home demo to draw out everything that was sentimental, conservative and frankly morbid about late period Beatles, and nor did anybody else. Producer Jeff Lynne did his best with what was available to him.

But maybe the wider public already sensed a bill of goods, and the prospect of the boys crooning "On Moonlight Bay" with Morecambe and Wise was never going to be enough to inspire anybody. Already the very early Beatles seemed ancient in the mid-nineties, as though retrieved from the previous century, as opposed to just over thirty years ago.

Hence the launch of Anthology 2 was by necessity lower key, and that was probably to its benefit. I don't really know what "Real Love" is doing right at the album's beginning. Again Lynne had only a home demo on cassette to work with, although at least this was a full song rather than a discarded fragment of one (or, more properly, a fusion of two songs on which Lennon had been working on and off since 1977 - "Real Life" and the later "Baby Make Love To You" - and which at one point had been pencilled in to begin side two of Double Fantasy). The surviving band members added discreet accompaniment; Harrison's doleful guitar is particularly prominent. But the end result still sounded stodgy and elderly and Radio 1 passed on the single altogether, figuring that "Real Love" was much more of a Radio 2 record.

Nonetheless, get past that and you enable a fascinating peek into what most people still consider the group's apex, 1965-7 (with problematic bits of early '68 tacked on). Most of Anthology 2 consists of alternate takes, and while it is sobering to be reminded how much they needed George Martin to bring sparkle to their songs - "Only A Northern Song" in particular sounds rather marooned and grumpily self-pitying without all the sound-effects and free jazz blowing added on later - it is also refreshing to hear how well they worked together as a group.

"I'm Down," for instance, has a storming vocal from McCartney which nearly cuts the released take (despite his pained cries of "plastic soul!" at the end). I will take the inclusion of the flute-free "You've Got To Hide Your Love Away" as a knowing nod to Noel Gallagher. Of the previously unreleased songs, Ringo does his weary best on "If You've Got Trouble" ("Oh, rock on, anybody!" he exclaims halfway through) but the band doesn't quite nail the song down, while "That Means A Lot," with McCartney on lead vocal, sounds recorded in the midst of a blizzard - the band subsequently opted to give the song to P. J. Proby to record.

One of the loveliest things of the 1965 edition of The Beatles was that they were still willing to do workaday television shows like Blackpool Night Out. The four songs from their second appearance on the show, recorded at the beginning of August of that year, find them in fabulously friendly form - Harrison introduces the solo public premiere of Paul's "Yesterday" in the style of Opportunity Knocks (fittingly, since that show's arranger Bob Sharples was also to hand on the show and provided the string backdrop).

This was all within a firmly mainstream showbiz milieu; the show's hosts were Mike and Bernie Winters, and other guests included Pearl Carr and Teddy Johnson, and Lionel Blair and his company of dancers. In that context, "I Feel Fine," "Ticket To Ride" and "Help!" must have sounded like "White Riot." We have already heard Paul's initial dry run through "Yesterday," which is plainly a work in progress (two lines of lyrics are transposed), but his Blackpool reading of the song (performed at the long-demolished ABC Theatre) was something of a sensation at the time, and you can certainly sense the excitement patiently running through the screaming core audience, who sit down, listen and empathise.

Barely a fortnight after that, the band were onstage at Shea Stadium, but even that atmosphere can't coax the Harrison-led "Everybody's Trying To Be My Baby" out of dreariness (and, puzzlingly, it is the only Shea Stadium performance included here - there is definitely far too much of George on this collection as a whole, and not nearly enough Ringo). There follows a fairly brisk run through the Rubber Soul era; both "Norwegian Wood" (despite Harrison's audibly inept sitar playing) and "I'm Looking Through You" are punchier than the album originals, but one must draw a diplomatic veil over "12-Bar Original," mercifully edited down from over six minutes, in which Harrison gamely attempts to be Clapton (one thing you should never have expected The Beatles to be is "authentic").

Of the Revolver material featured, all of it was worked into infinitely better finished shape. This "Tomorrow Never Knows" sounds almost insultingly indie (or even borderline Madchester baggy), with its weedy organ drone (one could be listening to the Mock Turtles, or My Jealous God). "Got To Get You Into My Life," minus the horns and propulsion, not to mention a finished lyric, sounds like a below-par Georgie Fame album-filler (though it's instructive that the organ-dominant soundtracks to both songs put me firmly in mind of Brian Wilson - this is nearly a Smiley Smile remix of Revolver). "And Your Bird Can Sing" simply proves just how great a pop group they were, despite all of them collapsing in fits of giggles throughout. "Taxman" - Neal Hefti via Allen Toussaint - sounds angrier. "I'm Only Sleeping" sounds drowsier, but you are never left in doubt how absolutely terrific the four of them, playing together, were at this peak.

Just to underline that point, the first half of Anthology 2 concludes with two songs recorded live at the Budokan - and they certainly clear a path for Cheap Trick. Despite all the talk about lousy sound and performance quality, this doesn't pan on audio evidence; the band are in tremendous technical form on both the Chuck Berry cover and the tricky "She's A Woman," the latter of which works up a head of steam comparable to that of "Surrender" a dozen or so years later.

They sound like the happiest and the best band in the world.

* * * * * *

However, as Oscar Wilde noted, happy endings only happen when you're not told the rest of the story.

There are, if you choose to find them, twenty-seven takes of "Strawberry Fields Forever," all entirely different. Only a few of them are represented on the montage offered here, but even that is sufficient to gain a good working idea of how the best band in the world decided to break the mould of pop, and they did, stop bullshitting me with your meticulously cynical hindsight.

You hear how the song patiently evolves from a simple acoustic guitar meditation; in Lennon's early "cannae do it" hands, it sounds like a folk roundelay from two centuries before (actually, what it sounds like is Donovan, and that is a great thing so shut up), pensive and timeless. Then this strange keyboard called the Mellotron pops up, and the tempo becomes one of sultry tropicalia (with Harrison's lead guitar instantly recalling Hank Marvin - perhaps this represents the endgame of "Wonderful Land"). The song is sung dazed with wonderment, but straight, with one verse leading directly into the others, and is given a very simple but profoundly moving Mellotron coda. One can still listen to that first studio take and be driven to tears, thinking of the potential futures which we know all got sealed off and closed down, the other paths The Beatles, or indeed we, could have pursued.

Then the more familiar sound of what is labelled here as Take 7, which forms the first minute or so of the final single mix, but here continues to drift into subtly different waters. All the way through, Lennon's determinedly confused I-am-what-I-am-but-am-I-me philosophising (a typically Libran lyric, as Lena pointed out) gently pushes pop music outwards; unthinkable without Dylan but also, at the time, arguably unmatched by Dylan (The Basement Tapes were yet to be recorded), and markedly less thinkable without the contemporaneous catalyst of Brian Wilson (think of "Wonderful"). We also get the unedited final dissolve, with cranberry sauces and Ringo being urged to calm down.

There is no need for me to be hypocritically cynical about what was the second pop record I clearly remember hearing (and watching its video on Top Of The Pops - the first record was "I Feel Free" by Cream) in the only chance I get to talk about it on Then Play Long. Both sides of that single formed me in ways which continue to have consequences. The record changed shit forever. "Penny Lane," here broken down into its components and with its radio ending, is if anything more disturbing in its refracted cheer than "Strawberry" - but don't take my word for it; Lena has written, with typical excellence and vision, about both.

It changed something crucial in the dynamic of The Beatles, too. "Sugar plum fairy, sugar plum fairy," mumbles John as an introduction to their greatest song, which here sounds like a reticent, even in part bashful (and certainly baleful), meditation on lives passing, things happening and perceptions changing. Lennon seems full of regret here, while Paul in his section is perhaps a little too gleeful ("Oh, shit!" he laughs as he fumbles a line). It is this hidden nook into which you sense they do not quite want you to peek, for fear of what you might find. The ill-fated Mal Evans enthusiastically does the echoed count-up, at this point over a bare backing track; the orchestra, curiously reminiscent of John Barry, swells up steadily, but instead of that final note you hear Paul in an ambient whirlpool, chatting about the difficulties of putting the song together.

Anyone wanting to be sneery about Sgt. Pepper can simply go and do one. Such people prefer not to realise how radical and comprehensive a citadel it was in its time - and yet the record was still, if in places only just about, the work of an integrated group of players. Here "Lucy" and "Kite" are enthusiastic warm-ups, and "Good Morning Good Morning" is a dynamic punk thrash - they hadn't mislaid their chops at all. But its whole, in its original context, was indisputably greater than its sums. Piper At The Gates Of Dawn, work on which began, at Abbey Road, as the work on Pepper was ending, is perhaps a compromise that doesn't adequately convey the semi-trammelled power of its creators onstage, but Pepper was only what it was - the reprise of the title song, which Hendrix performed on stage in London three days after the album came out, is messy but clearly enthusiastic in a "yay, we're nearly ready!" gallus (as we Glaswegians say) manner.

The major stumbling block here is the absence of "Carnival Of Light," which was pulled from the album at the last minute following objections from others, chiefly Harrison. This is perhaps the great gaping hole in any Beatles discography, and dull instrumental backing tracks for "Eleanor Rigby" and "Within You Without You" (which were brought in as last-minute replacements) do not compensate for its omission. It may well be thirteen minutes of aimless collaging and general mucking about (we have no way of knowing for sure - what turn up on YouTube are, at best, educated guesses) but don't we have the right to listen to it and make our own judgements (Tim Worthington writes well and fully about the piece here)? Perhaps next time I bump into Sir Paul at Sounds Of The Universe I'll ask him about it.

Furthermore it may be argued that "Carnival" might form the great bend in the Beatles river - because what we hear in the last quarter of Anthology 2 really doesn't sound like the work of a group. All of it was conceived and recorded after Brian Epstein had died, and suddenly the old camaraderie has fallen away, been stripped from the band's chassis. Lennon's "Walrus," which is basically just him yelling over a distorted electric piano, with Ringo manfully drumming behind him, sounds like a cry of bereavement. As for Paul's work, it's all very worthwhile stuff, but nowhere do you feel that "Fool On The Hill" or even "Hello, Goodbye" has much to do with "The Beatles"; if anything, these songs point to the seventies and Wings (there is a fairly firm line of development from "Fool On The Hill" to "Let 'Em In"). John is, likewise, left on his own, and on the closing "Across The Universe," he sounds as throatily exhausted as he had done on the guide vocal to "Yes It Is" near the beginning of this collection, and not at all far away from the lonely compromise of "Real Love." Perhaps that is the core lesson of Anthology 2; you try to conquer new frontiers, then stuff happens and where did the air go, why did we end up so blue?

Perhaps it is best to leave the group in the final flush of their partly-learned, partly-felt insousciance, the full, nearly six-minute-long version of "You Know My Name (Look Up The Number)," which to me, more so than "Revolution 9," is the track which sorts the Beatles wheat from the Swinging Sixties™ chaff - you think you love, or even know, the Fabs? Well, love this fuck-you-history romp, which not only points the way most directly to the seventies, given the obvious Bonzos/Python signposts, but finds the quartet in their natural element, irradiated by that vital irreverence. Having a laugh - remember that?