(#528: 10 June 1995, 2 weeks)

Track listing: Shine On You Crazy Diamond, Parts I-V, VII/Astronomy Domine/What Do You Want From Me/Learning To Fly/Keep Talking/Coming Back To Life/Hey You/A Great Day For Freedom/Sorrow/High Hopes/Another Brick In The Wall, Part II/One Of These Days*/Speak To Me/Breathe (In The Air)/On The Run/Time/The Great Gig In The Sky/Money/Us And Them/Any Colour You Like/Brain Damage/Eclipse/Wish You Were Here/Comfortably Numb/Run Like Hell/Soundscape*

(*On the cassette edition only, which of course was the edition I used for this piece)

A midsummer weekend of an afternoon it was, quite sunny for a time then cloudy. I was up at the top of Parliament Hill Fields with some friends and we ventured out of the pub and into the open to view that skyline, as it was (and no longer is). To the southwest of where we were standing you could hear music; it was coming from across downtown in Hyde Park and at this distance I can’t remember who was playing at the time. Consultation of the schedule reveals that it was probably Coldplay, doing a mash-up of “In My Place” and “Rockin’ All Over The World.”

It was Saturday, 2 July 2005, and we were listening to the Live 8 benefit concert (London edition). We dispersed and made our own ways home, promising to keep a televisual eye on what was happening. But for a while we also discussed at length that concert’s star turn (actually they were second top of the bill behind McCartney, but anyway) Pink Floyd and what, if anything, they still meant to us, and to life.

That evening, some distance southeast of Hyde Park, I watched Pink Floyd – all four of them – on television and, like Tony Christie, wondered why anyone else had even bothered to turn up. They performed that sequence from Dark Side Of The Moon and it rendered me back towards memories as deep as a sarcophagus.

You see, I couldn’t get my self (two words, it was deliberate) away from Pink Floyd. They were so central to my musical understanding and had long since instilled in me the notion that this was what exploration and newness should mean, that listening to every new album should be the equivalent of stout Cortez discovering the Pacific for the first time. They helped shape me. I listened to and absorbed Dark Side Of The Moon at an unhealthily early age and it helped define the world as I might perceive it.

Watching and listening to the same four musicians – having temporarily made their peace – playing the same music that night was almost intolerably moving, insofar as it moved me to wonder how music had allowed itself to stray so far from this acidulously compassionate template. It reminded me of whence I came; the preference of jazz to rock or pop, my father’s classical references, reading The Sunday Times (you could, in those days) while eating a Turkish Delight, the scent of the old Argyle Street branch of Virgin Records, the imposition of potential apocalypse.

It made me think of the great music which Pink Floyd helped enable – my two favourite albums (there is no greater music) are directly owing to the beneficence of one of the group’s members – and the possibilities which the early seventies placidly proposed. Where I might be aimed, where I might venture, apart from those golden Saturday afternoons wandering down Bath Street towards the Mitchell Library, or up on Kelvinside, descending the long hill down towards Byers Road, seeing the frontage of the Hillhead branch of Listen Records blinking at me as identifiably as the flashing light included in the packaging of this double live album.

And there was a pronounced symmetry to the compassion which I felt emanated from Pink Floyd’s Live 8 performance, as though they were speaking to me of reassurance and renewal, a timely reminder from a long-vacated home. I watched the audience, who were weeping in communion – and this is perhaps the most profound thing that music can do to a human being, to move them. The only question I asked myself that night was the conundrum that, just because everybody says that Dark Side is the greatest album ever made, doesn’t necessarily mean that it isn’t. You know, I thought to myself…it just might be. Name me one greater, not including the two that it helped to enable. You can’t. Can you?

I am not convinced to this day that Dark Side isn’t The Greatest Rock Album Ever Made. Well, all right; The Greatest Art Rock Album Ever Made. I know, this binary grading doesn’t help, isn’t going to prevent the collapse of civilisation – even though that is what the record, in part, is about, when it’s not about Syd, to whom Waters dedicated “Wish You Were Here” that Live 8 night; that would have been the coup de théâtre, wouldn’t it, to have had Syd come onstage and sing the song. But poor Syd was terminally ill in 2005 and in any case would never have comprehended any invitation, still less consent to it.

Still – all this stillness, as opposed to permanence - here we have the bulky, blinking double cassette edition of Pulse to consider. The band had not intended to release a live album scarcely a year after The Division Bell, but when it was noted that Dark Side was being performed in full, I suspect there was the intent of setting historical mistakes aright, since the original remains, at 4.3 million copies (and counting), the largest-selling album never to have a direct Then Play Long entry (although there is one indirect entry). Add to that plenty of songs from The New Album, most of their greatest hits (though several elements of The Wall find their way into this “Another Brick”) and Syd’s “Astronomy Domine,” unplayed onstage by the band since the early seventies, as well as the extravagant packaging, and you can see…

Well, actually you can’t – and there was a video edition released in July 1995 which in itself is not really sufficient either. It was the visuals which caused the main problem. Because the visual effects were so elaborate and complex, it meant that to trigger them, every performance had to be minutely precise, meaning that there was no room for improvisation. Hence, although I do not doubt that stalwart Floyd followers attended several of these concerts, this in essence is a staged musical, thus comes over as rather mechanical.

There is also an immense hole in the record which stalwart bassist Guy Pratt, whose father once co-wrote songs for Tommy Steele, cannot fill, and it is a similar hole to that of latterday New Order – as curmudgeonly and contrarian as the bassist might be, he is nonetheless essential to the group’s music as a whole, especially if he is that group’s main songwriter.

It is palpably clear throughout Pulse that Pink Floyd need the saturnine otherness of Roger Waters, since they otherwise sound like a competent but uninvolving tribute band (were The Australian Pink Floyd better at being “Pink Floyd”?). The hits and album tracks run without undue interest; one glimpses a pedestrian pompousness in parts of “High Hopes” which will lead directly to entry #579. The closing Wish You Were Here encore selections crave Waters’ Formica ominousness; this “Run Like Hell” might as well be “Run Like The Joshua Tree.” They make “Astronomy Domine” resemble – well, something from The Division Bell (whereas on Ummagumma it sounded like little else).

Possibly the musician who has most freedom here is backing singer Sam Brown, who cuts admirably loose at several strategic points throughout the record and indeed at times carries the music. But this Dark Side is a pallid Xerox of the original; the impact of “Great Gig” is fatally dispersed by dividing up the wordless, agonised improvised vocal between three singers (Brown, Durga McBroom and Claudia Fontaine – all excellent in themselves, but here they just get in each other’s way).

There is an air of scrubbed-up politesse about this Dark Side which perhaps makes one question the motives behind the original, because it seems to me that the album has become a convenient shorthand for not doing anything about the world’s shit. Buy it, listen to it, smoke dubious substances to it, make love to it (oh, I know all those demographics) and maybe you feel that you’ve done your bit, been seen to care. Just don’t lift a finger to do anything to change it, and the record doesn’t make any suggestions in that direction either, apart from a Marina Hyde-type shrug-cum-chuckle about it being a funny old world, it doesn’t matter whom you vote for ‘cos the Government always gets in, etc.

This compassion-at-one-size-fits-all-remove image is exactly why punk rose up against it. The Pink Floyd, they knew capitalism was all wrong and crooked, but, you know, they just sit in their mansions* and mildly grumble without offering a way out (*not actually the case; at the time the album was recorded, the band was nearly broke) as though we are really meant to grit our teeth, bear it and vote Conservative at the next election when no one is looking because humanity’s done for but, oh, our favourite coffee shops…

A default, go-to Compassion card of rock, like putting your spare 5p into the tin rattling outside Woolworths. But it needs the poisoned passion of Roger Waters; otherwise, this is a complacent Moon rising. Most of Pulse is similarly frustrating in its immaculate manners (although, listening to the introduction of “Time,” I marvel that it could have easily been played by The Shadows), and revisiting it for this piece was as tough an exercise as those seemingly endless forty-track double albums which clogged this tale up in the mid-seventies.

Why do I come down on it so hard, why is the shine on that diamond not sufficiently crazy? For an answer, I would need to go back to that Saturday in early July 2005; four days before London won the 2012 Olympics and for once could feel good and proud about itself, five days before London was blown to pieces (and a friend of mine killed, along with fifty-one other people, executed for the capital offence of going to work) by what Jonathan Meades might describe as “resentful hicks” (although, of course, it was nowhere near that simple).

If, however, you experienced London for the few weeks after that happened, you would have seen a new, or renewed, communality, with everyone pitching in to help, to soothe, to mourn, to regenerate, and maybe that encapsulates Pink Floyd’s modest contribution, even if it were only to point out that, if we’re in the same boat, the least that we can do is to help row it.

But it is possible that Pink Floyd will, ultimately, only represent a moment – and, in that final arms-raised-and-linked gesture to cap their Live 8 performance, one instinctively knew that we would never see this moment again. They were saying goodbye to us, and good luck. There are worse ways to absent yourselves from your audiences.

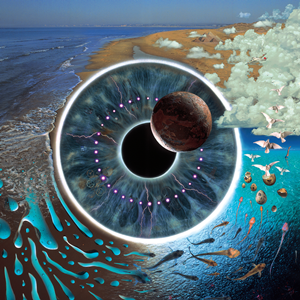

And perhaps their most patient and resonant farewell – for now, anyway; there is another Pink Floyd album to come, in the fullness of time – can be found in the twenty-two minute “Soundscape,” the overture to their performances which is absent from the CD edition of Pulse but fills up space on the second cassette. This is actually the group’s “Carnival Of Light,” though far less confrontational. All we hear are…sounds, of nature, of inquisitive humanity, the basis of Waters’ Ummagumma pastorales, of the sky, the sun, the uncomplicated 1971, the effects which we will re-hear in the songs themselves (e.g. the aeroplane) – and if this indicates a benign pathway to records like Chill Out, Space and U.F.Orb (Pratt also performs on the latter), then that is surely deliberate. But the overall impression is one of a sunny vacancy; idle, unending childhood summers, life before elements in the world destroyed a version of it, and – finally – space, the universe, the infinite, the unreachable but that doesn’t mean we don’t try. That midsummer afternoon’s scheme.