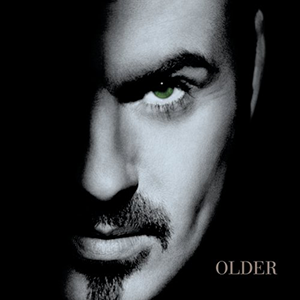

(#549: 25 May 1996, 3 weeks)

Track listing: Jesus To A Child/Fastlove/Older/Spinning The Wheel/It Doesn’t Really Matter/The Strangest Thing/To Be Forgiven/Move On/Star People/You Have Been Loved/Free

"When I'm in the casket I am immersed in a darkness unlike the darkness of night or sleep. This is a very deep, padded darkness and the feeling it brings is one of peace. The casket is set up upstairs and because it has some tiny air vents I can faintly and intermittently hear the sàárà going on downstairs. But for long stretches the darkness is accompanied by a profound silence. Sometimes when I've been in there for a while I hear a low and unfamiliar sound. The sound seems to be coming not from outside but from inside. The first time it happened I was mystified and a little scared. Only later did I realise that what I was hearing was the sound of my own blood circulating through my body, the blood in my own head. I was hearing in a way I hadn't heard before the sound of myself being alive."

(Teju Cole, Tremor: New York, Random House, 2023, p 146)

“It is never too late to be what you might have been,” sixty-one-year-old George Michael, remembering another George who wasn’t really a George (Eliot), reflects. “Then again, I'm surprised that I've survived my own dysfunction, really!”

This sounds like an extraordinary remark to have been made by somebody who for the last four decades has been acclaimed as one of Britain's greatest songwriters; Bushey's Bacharach. There is hardly an artist in pop, whether Céline Dion or J Balvin, who hasn't benefited from his work. And yet perhaps Sir George - he was knighted for services to music and charity in 2005 - may still regret, albeit in a small, unobtrusive way, that he has never really flourished as a recording and performing artist in his own right.

Those with long memories will recall that he might once have become a pop star himself. As part of the group Wham!, which his friend Andrew Ridgeley inveigled him to join, he was briefly fashionable when their first single, "Wham! Rap" - a subversive call for people to abandon the Thatcherite overwork ethic and exploit her system to do what they actually wanted to do - was released in May of 1982. Though not quite a hit, it gained sufficient critical approval for the band's record label to greenlight a second single.

In "Young Guns (Go For It)" the band turned its attention to the perils of marrying young and selling out to a system which might ultimately crucify them. Why be a boring adult, the song seemed to plead, when you can hang out with me and keep living instead? The band were very confident about this record and even devised an elaborate dance routine - with costumes involving leather and studs - in preparation for a hoped-for slot on Top Of The Pops.

That so nearly happened. Once again the critics raved about the song, and this time it was picked up by daytime radio. Catchy, punchy, cheeky and consciously danceable, the omens were good for it becoming a huge hit. The single entered the charts at number 72 and one week later had sped to number 48. It looked a near-certainty for Top 40 status and the associated TOTP appearance.

Then disaster occurred. In the following week's singles chart, "Young Guns" had, seemingly inexplicably, fallen back down to number 52. Wham! were astonished and not a little infuriated. They had been exhausting themselves preparing for what was now considered an expected television performance. What the hell had happened?

They got on to their suitably embarrassed record label, who referred them to their parent multinational distributor. The fact was that the single had fallen down the charts because record shops had run out of copies and no refresher stock appeared forthcoming. It turned out that the label hadn't pressed enough copies of the single to begin with. Perhaps it had only anticipated a mid-Top 75 showing, unlikely to cross over.

George in particular was angry. Very angry. He telephoned CBS' London office and let them know what he thought. He demanded that more copies of "Young Guns" be pressed. They were profoundly apologetic but explained that, with all due respect, Wham! hadn't been considered one of their priority artists for the season. There were new albums by Michael Jackson, Adam Ant and Marvin Gaye, not to mention an ABBA greatest hits double-album, due before Christmas and the company's pressing plants had mostly been turned over to producing those or preparing to produce them.

Sir George can now reflect that, had he been slightly more ruthless - by threatening to sue the record company, for instance (but what if the band lost? It would have been them against the music industry, and they didn't have any money) - the label might have relented and rushed out further urgent copies of "Young Guns" for the shops. Then things might have been turned around, the record might have gone back up the chart the following week and earned them that belated TOTP placing, and who knows what might have happened from there?

But, as things actually turned out, it was all too little and too late; "Young Guns" slipped ignominiously back down to number 70 the following week, then out of the charts altogether, and that was that for Wham!, who, frustrated and internally broken, agreed to split up almost immediately thereafter.

George was not looking forward to returning to the dole office and retreating to his bedroom. He felt the same sense of the rejected outsider as he had done when shuffling in and out of his classes at school, always on his own. Fortunately, during their brief dalliance with the music industry, they had made a few good and useful friends - contacts, if one must - one of whom rang George up a little while after Wham!'s split and suggested an alternative career as a songwriter for others. Though initially less than thrilled by the prospect - he'd been dreaming of going on Top Of The Pops for nearly a decade - it was certainly preferable to extended periods of wall-staring, and he duly set to work.

As a songwriter he quickly became one of Britain’s biggest; in 1984 alone he was responsible for Donny Osmond’s spectacular comeback hit “Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go,” Tina Turner’s global smash “Careless Whisper,” Alison Moyet’s “Freedom” and Cliff Richard’s seasonal radio perennial “Last Christmas.” He has over the subsequent four decades won multiple Grammy, Ivor Novello and BRIT awards and is universally respected. Yet in unguarded moments he often wonders just what it would have been like to perform his own songs, to become a pop star in his own right.

What would have become of George Michael, where would he be now, if he had?

* * * * * *

“so the words you could not say…I’ll sing them for you…”

When Laura died, at 11:30 p.m. on Saturday 25 August 2001, it took me just over four months to summon up the strength in order to begin The Church Of Me. When George Michael’s partner Anselmo Feleppa died, semi-unexpectedly, in 1993, it took him eighteen months to summon up the courage to write anything. When he did, the words of “Jesus To A Child” took just over an hour to come out, but I would expect that they’d been sitting in his head for considerably longer. And they only had two years together. Still – and note the unuttered stillness of “Jesus To A Child,” not to mention the Still of Joy Division – art, as with meaningful life, is more often than not a matter of patience, and George realised that well enough to call a subsequent album Patience. One must find reams of patience in order to grieve properly and fully.

His recording of “Desafinado” with Astrud Gilberto for the Red, Hot + Rio Aids charity album/video project marked the start of his fascination with the troubled tranquility of Antonio Carlos Jobim’s music, and Jobim’s example runs through and chills the spine of the Older album, slowing its pulse down to one of true meditation. Its opening song, however, initiates the culmination of the gradual slowing down and expanding out of George Michael’s music over the previous decade. “Jesus To A Child” is among the most patient of number one singles; it takes six minutes and fifty seconds for its story to be told, for its ghosts to be assimilated. It lasts for as long as is needed to accommodate and express the singer’s emotions.

Those emotions relate to two specific events; first, watching his lover die at the moment of death, unconscious but still managing one final smile before expiring (“kindness in your eyes/I guess you heard me cry”), and second, his reflections on what it means to lose love when, having known, felt and experienced the love of another person, love can never truly be lost. He sings with a near-heroic restraint; again, the façade of tranquillity to mask the non-articulated cries with only the trembling wings of a vacating angel which mark the fourth utterance of the phrase “you smiled at me” to betray something far deeper, or the stifled sob on the phrase “loveless and cold,” both in the second verse. And yet, with that secret smile, the dying lover with his last breath “saved my soul,” since the residual warmth of their love will shelter him “on those cold, cold nights” when the colder steel of the razor blade would have been an easier solution (and, needless to say, it is never a solution), as evoked by the poignantly chilling synthesiser chord at 5:32.

“and the love we would have made…I’ll make it for two…”

The strength to put pen to paper, the courage to continue with what is left of life, or rather to continue rebuilding what could still be of life; the memory of the departed lover, if properly cherished, provides the spur to carry on, through and beyond the pain barrier, against a world intent on not understanding (“sadness in my eyes/no one guessed, well no one tried”), until maybe, just maybe, you might find, through your courage or through the art you do your best to express in the words available to you, a new love, not the same as the old love, but a new life, a returned future. George does not resolve the song at its close (“oh the lover I still miss”) but he does leave his door open; for hurt, disappointment and ridicule, perhaps, but then, how else can love get through to him, or he to love?

Remembering his expressed admiration for Joy Division's Closer, we could view Older as an extension of this sort of aesthetic post mortem. It was not only Feleppa who passed away not long before this album was recorded, but also Jobim himself, who, as Michael says in his sleevenote, "changed the way I listened to music.”

Indeed, the regretful and poignant haze which wafts throughout the album could be considered a decompression and depoliticised extension of what Jobim achieved on his album Matita Perê; instead of the massed ranks of "disappeared," this record is concerned with two disappearances only - that of the Other, and that of the artist. The moment when Michael's alto floats in, embracing the word "kindness" over the aching minor keys of "Jesus To A Child," is worthy of Art Garfunkel or Green Gartside. A song of devastation sung by a ruined soul of a voice over the most delicate of Claus Ogerman-esque orchestrations. He is praying more to himself than to his lover. Eventually, as must always happen, the Other can only survive by being absorbed into himself: "So the words you could not say/I'll sing them for you/And the love we would have made/I'll make it for two." He is looking for excuses not to die.

(The above picture comes from the Fond/Sound website, and its excellent piece on this album should be read)

Before proceeding with this piece any further, however, I should now strongly advise you to go and listen to Matita Perê, released to little fanfare on New Year's Eve 1972, even though it commences with a straight reading of what many consider the definitive song of Brasiliana, "Águas de Março”; well, straight-ish, because Jobim’s mildly-amused double-tracked vocal is nicely subverted by a grave ‘cello drone and dots of wayward woodwind which eventually blend with Jobim’s whistle(s). Eventually the unison consortium of flute, piano, strings and subtle muted trumpet in the distance makes you forget there’s a voice, or are voices, in there. As though the singer were trying to forget himself, subsume himself within the music’s architecture.

In “Ana Luiza,” a romantic ideal as close yet as remote as Barry Ryan’s “Eloise,” there persists the feeling of a David Jacobs late-night Radio 2 MoR serenade gone slightly wrong. Note how Jobim’s emotional pain becomes palpable as the drums double up midway. He is searching, painfully, for this Ana Luiza, and either she’s fortified herself away from him in her metaphorical castle or merely exists only in his mind. “Por que me negas tanto assim a primavera (Why do you deny me spring so much)?” he asks, audibly on the verge of emotional collapse, or weariness of all worlds, as alto flutes cuddle his candour. But the song fades, unresolved; he can never refrain or retreat from his search.

The title song sees Jobim musing on “the half-life of postponed deaths” before widening his remit to incorporate the more sinister number of “seven hundred lives and seven thousand deaths,” as he meticulously names and describes just a few of the souls suffocated by the junta. A distant whip crack materialises as the song speeds up which could pass for a rifle being loaded. Lengthy string pauses forcing you to think. The song proceeds as though he is creating it as he goes along; the music fits around the words, which in turn narrate their story with patient pain. “On the old path where the mud hangs” – hangs? – might be a path similar to the one George Michael treads in these strange, isolated portraits decorating Older’s inner sleeve; the deserted railway shunting yards, denuded of people. “In the rose garden of dream and fear…In the glare of the waters, in the black desert…” – the random sights, the unvoiced horrors, the realignment of a once-familiar landscape.

But then the singer’s voice disappears almost entirely. As with the Bowie of Low, he vanishes into his own cloistered creation. The album now mostly consists of extended orchestral pieces, with occasional vignettes, in some places superficially soothing, in others politely provocative. Jobim himself briefly returns in the second section of “Cronica Da Casa Assassinada” (“Chronicles Of The Murdered House,” the title of a 1959 novel by the Brazilian writer Lúcio Cardoso), the album’s emotional apex. In the one verse he allows himself to sing, Jobim sounds uncannily prescient of Michael (the opening “Feel sorry for me/Just listen to my woes” might serve as a less-than-kindly précis of Older).

Yet it becomes gradually clear, as Jobim speaks of neither day nor night offering him solace, that he is not merely singing for himself but for an entire vanished, or suppressed, civilisation. A cyclical piano figure turns up as punctuation throughout the instrumental remainder of the piece, with masterful and occasionally threatening compositional and orchestral elements worthy of Carla Bley or Gil Evans at their deepest and therefore finest. Look around this world you helped destroy, fellow citizens, and despair.

There is little left to say after that, but also a universe of things to say. The album concludes with two orchestral portraits, “Rancho Das Nuvens” (Ranch In The Clouds) and “Nuvens Douradas” (Golden Clouds), both elegantly and eloquently steered by Urbie Green’s trombone of immense melancholy, as though the fight for life were now over, and a better afterlife – or, perhaps more importantly, a better future for the generations to follow – is found by approaching The Light.

As though it felt good to be free.

* * * * * *

One might expect to be instructed that Michael’s rivers of internal grief count as nought against such a ruthlessly-ravaged world as Jobim catalogues throughout Matita Perê. But the inflicted pain on civilisation does not negate, indeed most likely helps facilitate, the pain of the individual. If we cannot recognise our own pain and work to resolve it, how are we expected to resolve the pain of others?

Then again, grieving people do uncharacteristic and frequently irrational things in the immediate aftermath of bereavement.

“My friends got their ladies/They’re all having babies/I just wanna have some fun.”

The early Wham! hits were exemplars of militant hedonism, finding rebellion and defiance in the act of putting off the awkward, tedious state of being known as adulthood for as long as possible. The most pertinent of those was “Young Guns (Go For It)” where George warns Andrew not to dive into early marriage (“Death! By! Matrimony!”) and enjoy himself for as long as possible. But years pass, people develop and change – and does the mindless pursuit of pleasure feel so rewarding and pleasurable when you’re in your thirties and you’re the only one you know left doing it? “Fastlove” finds him, now thirty-two, making his way into the night “in the absence of security,” cruising perhaps the same Bushey nightclubs for a pick-up, avoiding the stares which are a mixture of pity and contempt. Utilising the same bpm and sensual R&B tempo as Mark Morrison’s contemporaneous number one “Return Of The Mack” but several hours later, as signified by Andy Hamilton’s kerb-crawling saxophones, George is in self-denial, wanting a fuck and nothing but a fuck (“I won’t bore you with the details baby”) in a desperate attempt to obfuscate the “bad luck” that he’s just had (“what’s there to think about baby?”), sex to stop him from crying.

And then we come to the emotional crux; as George briefly splits the façade open and admits “I miss my baby” (though note the tremble in his second “ease my mind”), we hear fading in behind him the chorus from Patrice Rushen’s “Forget Me Nots,” a top ten hit from that month of May 1982 which snuggled in so securely with New Pop – it was also the month of the first release of “Wham! Rap” – memories of the only time when he was uncomplicatedly happy, when the sun shone its yellow, when he could still get away with any of this. However, his own refrain goes “Gotta get up to get down” and that is what is happening with him here; his half-seduction, half-plea of “So why don’t we make a little room in my BMW?” which he sings as the virtual antithesis of a turn-on, as though he’s asking her – or him – to check his pulse in order to ensure that he is still breathing.

The song eventually dissolves into synthesised nocturnal traffic sounds as the backing chorus insists: “Oh you really oughta get up now” (but maybe don’t bother to wake me up before you go-go) – out of the dream, to face his grief, to come to terms with his effectively having cut himself off from the world as middle age begins its subtle encroach. Wake yourself up before you go…go. Sex has rarely seemed so empty on a pop record, and George, no longer the young gun, sounds as though he has barricaded himself in that same room, watching the world do other things without him.

What can we do about, or with, this George Michael - leave him there in that BMW, stuck in first gear at Hyde Park Corner, in the forlorn hope that there has to be redemption of some kind? As the song stands it’s one of the saddest and least resolved endings to any extended run of number one singles. After all, his BMW cannot embrace him back.

With the album’s title track, however, George trades the back of the nightclub for the floor of an endless hall of pellucid marble (the record could easily have been titled Escapism) which he treads as slowly and solemnly as Jeremy Thorpe once walked the floor at Marsham Court; when I hear “You were there, and I was breathing blue” I instantly picture Thorpe – or at least the restructured Thorpe personified by Hugh Grant in A Very English Scandal - desperately reiterating to Norman Scott about how he (Thorpe) is not the man he (Scott) wants.

There is no talk of withheld National Insurance cards here, however – unless you catch the sinister tag of “or maybe you won’t” after Michael’s second “you’ll be fine” – but simply a grand and only slightly (and deliberately) stolid representation of how the tra-la days of youth are over. Then again, we have to remember that George Michael was, at the time Older was released, the same age as Charli xcx will be next month (at the time of writing) – perhaps “Outside” was his belated “Von Dutch” point of self-release.

Nevertheless the song “Older” is a self-motivated dimming of bright lights, pacing its hover between two sets of suspended chords – E and G minor sevenths – in which the world is voluntarily drawn in, as though to indicate: look, this is what happens when you age (“Change is a stranger who never seems to show”) and when the things which once attracted you now vaguely repel you. Or less vaguely in “Older”’s case, since Michael sings of “the same old fights (again).” In the background, Steve Sidwell’s muted trumpet sits at the singer’s shoulder like a betrayed cushion. In this song he looks even further backwards than he did in “Fastlove” for salvation, seeking refuge with a former lover. But this is instantaneously doomed because he cannot fail to see him/her as a replacement/substitute for the lover who has just died. It is a mistake which Sidwell’s trumpet admits with wearied beneficence ("I never should have looked back/In your direction").

“Spinning The Wheel,” in which Michael mildly admonishes a restless would-be lover, is trip hop-lite as the Bee Gees might have imagined it – those Gibbsian harmonies of “I-will-not-ac-cept” in the chorus (“accept” is a very Bee Gees word) with ghosts of muted trumpet and saxophones flying in and out like recalcitrant moths, or perhaps someone is playing Dummy slightly too loud downstairs from Sebastian Faulks; the “lover” is of course a serial risk-taking (antiretroviral drugs had not yet been formally tested) cheat but Michael sings of his betrayal in a detached, puzzled way – don’t I give you what you want? Weren’t we once strangers? – before deciding, no, this fellow’s going to kill me if he carries on behaving like this; note the double entendre of “standin’ in the rain.”

Whereas “It Doesn’t Really Matter” is Older’s second quietest and happiest song; he and his lover are at home, relaxed and happy. The underlying music is mellow and unobtrusive (barely more than Fender Rhodes and drum machine) as the singer twirls around what the outside world, including his lover’s father, thinks or might make of what they have before warmly and gently confirming that it’s completely fucking irrelevant what they think; we are here, we are now, we love and that’s how it is. Or you might consider it the record’s bitterest song, an appendix to “Spinning The Wheel” - it's all pointless; the true lover doesn't exist anymore, he can't just die, well yes he could just die because that's actually what he wants to do, doesn't want to spend the next fifty years in the waiting room, oh boy is he trying to convince himself that it's all nothing, it's all over, it is spent, it is history, no it is part of him and if you throw that away, best throw yourself away too

“’Hold me,’ she said, ‘Love me to death’"

(Manic Street Preachers, “The Girl Who Wanted To Be God”)

“Take my life. Time has been twisting the knife.”

“I think I would like to call myself ‘The girl who wanted to be God.’ Yet if I were not in this body, where would I be—perhaps I am destined to be classified and qualified. But, oh, I cry out against it. I am I—I am powerful—but to what extent? I am I.”

(Plath, Letters Home, circa 1949)

“The Strangest Thing” tends to get sidestepped in overviews of Older, but for me it’s the record’s key song, and unquestionably the darkest in this very darkly-presented album – it could have been entitled Let There Be Light – as well as perhaps its simplest, at least in terms of arrangement; the mournfully-ranging chord structure floats between F minor and B flat minor modes with unexpected but haunting ascents, or descents, to E major seventh and E minor before settling again, rather despairingly, in F minor. It bears an indistinct Eastern influence and possibly a more distinct Greek/Cypriot one (that bouzouki button on the keyboard?) – I picture a slowed-down reading of something like Haris Alexiou’s “Otan Pini Mia Gineka,” with its reeling, refractory refrain of “You’re telling me not to get drunk any more/Because it’s not allowed/But in my heart, THE WOE…/YOU DON’T LOVE HIM!!!!”

George sounds as though he’s performing the song in some dusty back room of a mansion, or maybe in the front room of a flat overlooking Botley Park one tiring Wednesday mid-afternoon. There does not seem to be anybody else in attendance, not even the “thief in my bed” who might well be the “liar in my head.” But he is in acute need of tactile reassurance in order to avoid rooting us in a potential grave. "Take my dreams/Childish and weak at the seams/Please don't analyse/Please just be there for me" because I'm not ready, might not ever be ready, to re-enter the world, to connect with humanity again - just hold me that's ALL I want, you understand, you know what's going through me, I need I need I need…

…”To Be Forgiven”?

In 1996 certain things have not yet happened to George Michael, so we have to be careful about cursed hindsight since there will be plenty of opportunities to exercise the latter nearer the time. Thus people find it easy to mark “The Strangest Thing” as a warning hiding in plain sight – but what is it that RAYE sings in “Genesis.” again? “You try to muster a flare, to tell somebody you're sinking/But anxiety is an index finger pressed to your lips.” Or what SZA declares in “Saturn”: “If there's another universe/Please make some noise/Give me a sign/This can't be life/If there's a point to losing love/Repeating pain/It's all the same/I hate this place” (italics mine).

So all elements contained, or condemned, within “The Strangest Thing” are of hushed, polished politesse, all the more efficient to conceal some of pop’s most hurting words - “Take my hand, lead me to some peaceful land, that I cannot find inside my head,” “I am frightened for my soul.”

If you imagine this is all leading us to an album which Older in part kept off number one, you’d be correct:

Everything Must Go – its alternate title could have been Nothing Stays Empty – is about a gap, and how that gap can be filled. Some of its words were written by a man who with gradual abruptness disappeared. His absence remains unresolved, so minding his store takes priority over mourning – because maybe, just remotely maybe, there is no reason to mourn?

As a consequence of this unresolved absence, the record is necessarily uneven. The songs where they surge forward as a refurbished unit in themselves work better than the ones written around his words, although the line here is blurred; “Kevin Carter”’s dynamics of triplicate symbiosis are worthy of peak Police, but its words are his.

But move forward, and in their own Blackwood way fight back (if only their own tears), they must. If “A Design For Life” is a mighty, if not wholly uncritical, portrait of how the working classes can better themselves without first waiting for permission to do so – libraries give us power because they democratise the accumulation and redeployment of knowledge – then it is also one of the boldest “I DON’T WANNA DIE” proclamations in rock, up there with Foo Fighters’ “Walk.” Mike Hedges’ trebly echo of a production confirms a direct lineage from Pete Wylie and Wah!

You can see the band, as it had to be in 1996, physically fighting to live as Bradfield and Moore leap and dance around each other’s guitars when performing the song on Channel 4’s TFI Friday show – they apparently did something similar on their two performances of the song on Top Of The Pops, which we unfortunately miss on both occasions because the cameraman was too busy wanking over the string section – and palpate their need to survive and hopefully prosper.

The album as a whole deals with imposed isolation – societal as well as the three performing musicians – and how best to handle it. “Australia” superficially sounds like a Dynamic Rock Anthem but is actually about being so pissed off with and tired of life that you’d run as far away as possible to escape it (see also the instrumental “Australia” by the Associates, also produced by Mike Hedges, and we’re far from finished with them…). But it would be unbearable without its vivid coat of hope; the title song spells out to their existing fans why they’ve been forced to change, why they can’t stay in the past and especially not his past, and why they have to keep going. The unaccompanied (except by echo) drums at the end of “Design,” echoing Rick Buckler at the end of the Jam’s “Funeral Pyre” but at quarter speed, indicate a gap which he should be filling and completing. The closing moments of the record’s final song, “All Surface No Feeling,” feature him clunking away on rhythm guitar.

Listening to his words, one does of course understand immediately why the Manics had to transcend this. “Elvis Impersonator: Blackpool Pier” (which one? There are three piers in Blackpool. I like to imagine he’s talking about the South Pier, small and isolated miles away from the town centre – the Tower is the merest of specks in the distance – where in the autumn of 1974 a red-faced man emerged from the theatre, begging sunbathers to come in and see Freddie Garrity in The Jolson Story [“Plenty of seats left!” I bet there were…]) mostly consists of outdated American jibes, as though Reagan were still President. “Small Black Flowers That Grow In The Sky,” though obviously heartfelt in relation to the brutal treatment of animals, is mostly notable for Bradfield’s very Cobain-esque delivery of the phrase “you’re bred dead quick” and the song’s title. Oh, and for Julie Aliss’ harp.

However, it is very clear that the band needed to escape that particular dead-end, or refashion it into an unexpected new trunk road. And the clear advantage they had over George Michael – even though most of Everything Must Go’s songs dabble with similar lyrical themes of alienation and depression, they fight those symptoms rather than philosophically and dolefully accepting them – is that they were a group, whereas with George Michael there was only one of him. Nobody, not even (or especially) an Andrew Ridgeley, to argue with or be pushed by. Just the occasional David Austin. No one else. Those immense spaces crying out to be filled, and not with that peculiar smoke either; bummed out at four in the afternoon, sprawled across a sofa, watching crappy daytime television.*

(*and maybe he wasn’t the only major musical artist thus largely occupied, but more about the other one anon…)

OR THE ONLY MAJOR MUSICAL ARTIST CONTEMPLATING JUMPING INTO THE RIVER (“I’m going down/Won’t you help me, save me from myself?”). "The cold, cold water is rushing in...maybe the child in me/Will just let me go." Is he considering suicide? He has tried but cannot get over this obstacle, calling your lover an obstacle, the very idea, the nerve - he cannot get past the pain. WHAT HAVE I GOT TO DO OR SAY TO CONVINCE YOU? Nothing. I have to convince myself. It's only me who's stopping me, as he contemplates on the song “To Be Forgiven,” the closest proximal body here to Matita Perê. The synthesised flute, drawing shut (thereby shutting out the world) the opulent curtains of the average late Sunday night Radio 2 listener, or mimicking the descent of the distressed body into the water, not yet finally at peace.

Michael endeavours resolution in the curious “Move On,” a Prince-like, fussily synthetic and Arctic synth-jazz groove complete with a fake supper club audience (and probably synthesised jazz players). His almost Gibb-like vocal fragility struggles to keep up with the decided onward motion of the bassline. Do we believe him? "Everybody thinks I'm doing AOK/They ought to know by now."

In "Star People" George bitches about empty celebrity. Of course it is a torrent of self-hatred directed against himself, despite all the "girl" references - "there's a difference between...you and me." "Without all that attention you'd die...I'd die. We'd die...wouldn't we? WELL WOULDN'T WE?" The music is too slow, restrained and polite to convince me, and it certainly doesn't convince him. "Who gives a fuck about your problems, darling/When you can pay the rent...how much is enough?" Look out and beyond yourself – as he eventually does on the far more purposeful remake “Star People ’97,” a nightmarish yet finally liberating inversion of (and inevitable sequel to) “Club Tropicana” which further closes the Wham! circle by explicitly quoting the Gap Band’s “Burn Rubber On Me,” the song which, when played on Capital Radio in late 1980 or early 1981, caused George to leap out of his bath and decide this was how he wanted to make a living.

Because it’s preferable to not living.

* * * * * *

It is at this point that I should perhaps speak a little about the upbringing of sensitive young boys in the context of families uprooted, voluntarily or otherwise, from abroad. I much enjoyed reading Pete Paphides’ memoir Broken Greek, in which he describes his years growing up in a Greek-Cypriot family, mainly in and around Birmingham with some extended home visits to Cyprus in the seventies (the Turkish invasion of 1974 eventually put paid to the latter).

I myself grew up in a Glaswegian-Italian family, mostly in Uddingston, a commuter village about seven miles southeast of Glasgow in which everyone was well-off except us. My peers at school – it would have been a stretch to call them “friends”; let’s just say they tolerated me – all lived in fully-detached houses in Kylepark or Douglas Gardens or that bit just off New Edinburgh Road. We lived in a first-floor tenement flat above the Bay Horse Inn pub. Money was tight, so tight that my mother was compelled to return to work at Tunnocks when I was ten in order to pay the bills. My father was, shall we say, professional to a point but ultimately feckless. Some of that has leaked through to my own DNA, not to mention his heart problems which eventually felled him on 15 July 1981, eleven days after his fiftieth birthday.

My father was from Glasgow and really that was as far as my paternal family went; his father Denis died in 1965, barely into his sixties, when I was one. My mother was from Filignano in Italy and most of her family were still alive and active, many of them as it happened in Lanarkshire and Glasgow, so overwhelmingly I felt as though I was growing up in a decidedly Italian household, with all the stuffy religious and societal conservatism that normally entails. One was supposed to smile and wave meekly at largely indifferent (to and towards me) people because that’s what little Italian boys were meant to do. Apparently.

The problem with me was that I was a misdiagnosed child prodigy. I was all over the front pages as a transient novelty item in the late summer of 1967. He was reading and writing from the age of two? Perhaps my parents glimpsed a gigantic cash cow. And of course, being a boy and not a prototype money-making machine, I proved extremely reluctant to fulfil these expectations and suffered for it as a result.

In retrospect I shouldn’t have had to go to school at all. A big mistake. Neither pupils nor teachers ever properly connected with me. But since my parents were unable to afford expensive private tutors, off to Muiredge Primary and then Uddingston (downgraded) Grammar School I was forwarded.

It wasn’t really a fun time. I qualify that statement with “really” because I quite enjoyed going out by myself on a Saturday and looking around the sundry book and record shops then in Glasgow, topped up by a fact-finding trip to the Mitchell Library or a visit to one of the city’s many cinemas. But naturally and inevitably it wasn’t good enough for others, i.e. my parents. Why wasn’t I mixing with other boys? Why wasn’t I going out at night and socialising? What was wrong with me?

It didn’t help that my father in particular had instructed, a.k.a. ordered, me to concentrate on Passing My Exams and getting into a Big University. And I had better come top of my year at school otherwise woe betide me. I never managed that. My father furiously whacked me about when in one year at primary school I came third. Out of a class of thirty-two. I don’t think they became as bothered about that in my secondary modern (for that’s what Uddingston “Grammar” really was) years. Always the science-orientated smart-alecks came ahead of me in the rankings (I was decidedly of the arts stream, and moreover the Pope’s a Catholic).

But anyway that was to be my priority. I was not allowed to have a girlfriend. This ruling was not aided by my parents’ subsequent frustration about why I didn’t have a girlfriend. Decades later my mother would exclaim delightedly about the former classmates of mine which she met down the road and proclaim that girls were queuing up to go out with me. Permit me to proclaim in a contrary fashion, oh no they weren’t. Mostly at the time they took the piss out of me and pretended to fancy me. By the law of averages maybe two or three of them meant it but I had already decided in myself that I would prove the world’s worst boyfriend (and I still reckon that at the time I was right to think such). I was profoundly uninterested in playing sports. I was not a “jock” (the rugged rugby types got the girls anyway). I was awkward.

Before I had the chance to reach university on a full-time basis – just before - my father had died, so I was left somewhat confused about how to proceed to life as an adult. I made mistakes and consequently alienated most of my fellow students. I said most, not all. But I’m not sure I was ever free of those stifling bonds of expectation.

Pete Paphides is about five years younger than me, so his experience of discovering, listening to, watching and cherishing pop music is necessarily different from mine. In Broken Greek he displays a commendable ability to recall exactly what records he bought and when, where and why he bought them, which suggests either an enormous memory or a handy diary (since I’ve never kept any diaries, my memories are only vague and approximate. I can tell you how I discovered Perspectives by the Stan Tracey Trio in a Cambuslang newsagent’s for 10p, but beyond it being a Tuesday lunchtime sometime in the late summer of 1979 I cannot be more specific, which means it was probably mid-1980 but ANYWAY…).

However, the underlying motive is the same. Music was, for both of us, an escape route from an otherwise stultified and straitjacketed life. Particularly with regard to me, as I wasn’t really allowed to buy records at all, and how furious my father would get if he caught me doing so, which was a lot more than once. After multiple beatings and yells I resolved that nobody in the future would fucking tell me not to buy records. It was posthumous revenge. Mercifully it doesn’t seem that Pete Paphides had to put up with any of that (indeed, he spent three of his earliest years not speaking at all - selective mutism is the medical term).

But there is still the Greek-Cypriot thing, the need to prove oneself to one’s peers – something exercised by parents rather than children – which, he said about to connect this section back to the piece’s main subject, is what people like Paphides and myself have in common with George Michael. A friend of Paphides’ father apparently knew George’s father personally, and when, parallel universe plot spoiler alert, CBS saw sense and pressed up some more copies of “Young Guns (Go For It),” ensuring that the single reversed back up the chart to number 42 – and how lucky that it was a relatively slow week for the charts, hence Top Of The Pops were able to accommodate Wham! on that week’s episode (Thursday 4 November 1982, Pops fans) – the fathers watching the show exclaimed with joy when young Yiorgos came on – indeed, opened the show - in the sense that “we” (i.e. expatriate Cypriots) had won.

Did George ever really get over those years of being non-“fit” and ignored, sitting on his own in a double seat on the school bus (although I seem to recall that his father might actually have driven him to and from Roe Green Junior School and Kingsbury High)? Did he ever manage to banish the admonitory voices from his childhood reiterating that he was a failure, even if they were only heard in his mind?

All I can do is speak from admittedly unique personal experience, but I can officially confirm that no, you don’t. The metaphorical manure brushed onto you in childhood does not get entirely banished or outlawed. Rather, it shapes the whole of the rest of your life, how you behave towards and relate to other people, how you react to and interact with “the world.” As I said before, I have to be extremely careful about what I say apropos George Michael here because there’ll be nothing left to say about him in the multiple occasions when he does revisit Then Play Long. But the impression with an awkward individual who doesn’t know quite how to deal with the world other than keep it at arm’s length, or do good things but endeavour to distance themselves as far away from them as possible – what is the worth of a good deed, or indeed a human being, if nobody knows that you’ve done one? – remains.

That supremely awkward thing of having to deal with people, living or not.

In “You Have Been Loved,” Michael, for the first and only time on this record, is forced to realise that other people might have been affected by Feleppa’s death, and possibly more profoundly so. The song’s first section – so calm in its architectural concealment of emotional wreckage – speaks of Feleppa’s mother, and perhaps at one remove George’s own mother (who passed away the year after Older was released, hence recasting the single of the song as an inadvertent additional elegy). She is on her way to the cemetery, past a school which has not changed “in all this time” (such a sigh as Michael phrases that); she meets the singer – they are both there to lay flowers at Feleppa’s grave, landlocked in mutual incomprehension. She cannot understand – might not want to understand (like most if not all mothers, in her eyes her son will always be a boy, even when referred to as a man) - why her son is no longer alive.

Then Michael turns the song towards himself; he pays due tribute to Feleppa in a lyric so tactile, fragile and moving that to analyse it here or anywhere would irredeemably cheapen it (“Please don’t analyse”), but still he thinks of the mother, possibly both their mothers, sitting quietly in an empty house, searching for their “crime.” And he does not convince anybody with that “So these days, my life has changed/And I'll be fine” – the objective melancholy of the Pet Shop Boys’ “Being Boring” does not apply to this song (there is no mention of parties or happiness of any variety) – and what is more, he audibly fails to convince himself. Nevertheless, the problems of the mother, or mothers, or of the billions mourning Princess Diana – the single of “You Had Been Loved” appeared in the midst of that period of voluntary collective mourning – did not cancel out those of the singer, and they never truly would…

Princess Diana, whose funeral we attended on Saturday 6 September 1997, four years to the day before I attended another funeral, and obviously I think of climbing Dunstan Road and walking towards Headington Cemetery when I listen to the first verse of “You Have Been Loved” and I was the one who sat at home – a long way away from Headington – searching for my assumed crimes until I realised I hadn’t been the one committing them. But anyway; you have been loved, which is better than not being loved at all.

“Forget all you learned from yesterday

If you learn how to change, you'll change today

I sing for you, so you can find your way home

I pray for you”

(Nearly God, “I Sing For You,” 1996)

* * * * * *

APPENDIX ONE: LOOK FOR THE MAKER AND WHISPER

It is as though the television viewer, watching unspeakable atrocities in his living room, in “Little Things (That Keep Us Together),” has gone nowhere and perhaps not changed enough, if at all, in the succeeding quarter-century. In 2024 they might still not have changed, other than watching new or refreshed atrocities on a claustrophobic, stroke-inducing computer screen (the horrible theatre audience in the video for “Genesis. Part II” staring, frozen, at a huge, numbing rectangle artificial light, bordered by surrounding black holes of darkness, as though hiding from actual natural light).

Tilt is every much a considered study of diseased solitude as Older, both records unveiled by singular artists in the trail of a lengthy absence from the public (then again, it’s all relative; I partly lived in Chiswick for two-and-a-half years in the mid-1990s and did wonder about the tall cyclist in shades I used to see darting about the High Road).

I’m not sure it comes to much of a resolution, either, Tilt; that would imply that nothing further needed to be said – although The Drift, eleven years later, violently corrected that delusion, not to mention all the other work he’d been doing in the interim; writing and recording film soundtracks, producing others, keeping a kindly but firm eye on Meltdown festival proceedings, contributing to compilations of songs, singing a James Bond theme, even.

Everything in Tilt happens in the world; nothing in it happens outside of the artist’s head. Like George Michael, Walker enjoyed complete control (perhaps GM needed a Peter Walsh figure, an outside producer, to help him see a more extensive light); the question being, was there anything really left to enjoy in either’s art?

There is, however, no light in Tilt. A lot of extremely dark humour (“In case of thigh”) but no light. Even George gingerly opens the back door towards the end of Older to allow a degree of light to penetrate.

I loved Tilt in 1995 and still love about half of it now. “Farmer In The City” answered all the questions about where did that beautifully-voiced balladeer Scott go, except nobody chose to listen or acknowledge, and secretly wished it could be 1965 again (well, it was 1965 again, but the 1965 of Stockhausen’s Momente, rather than comforting oldies radio and nostalgic television cut-and-pastes; “nobody, nobody may ridicule me,” “what are you upset about?”). The song is about Pasolini and Ostia and what may or may not have happened, even though whenever I hear “do I hear twenty-one, twenty-one, twenty-one? I’ll give you hear twenty-one, twenty-one, twenty-one” I immediately think of the twenty-one years Michael Henchard spends in remorseful sobriety after drunkenly auctioning off his wife and daughter for five guineas at the beginning of Hardy’s The Mayor Of Casterbridge. It is as universally embracing and poignant as “Jesus To A Child,” bearing the feeling that the song had to be carved out of proudly stubborn stone.

I also continue to adore “The Cockfighter” with its halfway house between Steve Albini quiet-LOUD alternations and Magnus Lindberg borderline-of-bearable extremities (specifically Kraft, for which I direct the curious reader towards the 1988 recording on Finlandian Records featuring the Toimii Ensemble and the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra under Esa-Pekka Salonen). Alternatively you could view it as a mongrelisation of the more extreme moments of Scraping Foetus Off The Wheel (the Adolf Eichmann part) and Andrew Lloyd Webber (the Queen Caroline part) – the searing moment when “she opened the tent to tame a morsel of air” – cue Brian Gascoigne’s perfect opening-of-Tallis-Fantasia string chord – “before the sun came up” and the deceptive black hole of noise devours as fully as the Tube train does its remaining passengers at the end of Geoff Ryman’s 253 (set on Friday 30 January 1995). And the bingo/rifle clickety-click double entendre; never neglect Scott’s humour.

After that dynamic double opening, however, the record becomes hard-going. “Bouncer See Bouncer,” sung as Number 6 being repeatedly jumped upon by Rover (“Spared? I’ve been SPARED!”), extends just beyond tolerance, other than the glorious, floodlit “I LOVE the city” interlude. No doubt the relentlessness was dramatically deliberate. “Manhattan” doesn’t really venture anywhere compelling, but “Face On Breast” balances its elements of third/fourth album Peter Gabriel (percussive internal threats), Johnny Ace (“am I only Pledging My Love?”) and Roger Whittaker (the community whistling) with aplomb.

“Bolivia ‘95” is David Sylvian as sung by Prince (“Lemon blood-y co-LA! Lemon-bloody-coooo-la”). “Patriot (A Single)” (not really, Scott’s joke again, it’s about the Gulf War) is slow, glorious and in places incandescent (John Barclay’s yelping hounds of multitracked trumpet, stoned/abandoned military marches, heart-rendering orchestral verses, bridges and coda). The title track sees (I think?) guitarist Hugh Burns, so sensitive on “Jesus To A Child,” explode in atonal fury; it’s the solo he had been threatening to play since Rafferty’s “Baker Street” and it plays as though Walker had suppressed a scream for thirty years and could contain it no longer. The only way to end the record comes with “Rosary”; Scott alone, singing of messy sexual encounters as though, well, there was a thief in his bed and, musically, it was still the sixteenth century (“Woefully Arrayed,” “I Love Unloved,” that type of Tudor thing – “Thee love I entirely; see what is befall me!”). Like George, Scott has no option at the record’s very end but to quit. Singing? Living? Or did he simply realise how good it felt to be free?

APPENDIX TWO: WHO IS THAT STRANGER IN YOUR VOICE? IS IT SOMEONE HERE WITH ME?

(above picture from Cherry Red Recordings)

During the three years I’ve spent contemplating this piece – although I’ve only spent about two months actually assembling and writing it – I realised I’d have to incorporate Billy MacKenzie into it somehow, but didn’t know how I could.

The dilemma was resolved for me when I came across a Substack piece written in January of this year by a gentleman named David Ross which explicitly compares the George Michael of Older with the MacKenzie of the mid-nineties. Not only that, but Mr Ross has also compiled a playlist entitled The Soul That Sighs, a sort of album-within-three-albums – a thorough three-CD anthology of MacKenzie’s mid-nineties work, in collaboration with Steve Aungle, entitled Satellite Life: Recordings 1994-1996, appeared in April 2022. The collection is structured as three separate virtual themed albums, but what Ross has done is to select just eleven of its thirty-nine songs and carefully re-sequence them in a way which is roughly comparable with Older. Two souls which weren’t just lost, but unjustly frozen out of the mainstream – the injustice doesn’t diminish simply because one of them was responsible for his own freezing. One soared above the radar, the other vanished beneath it.

I don’t think a song-by-song comparison between the two “albums” would be particularly viable or helpful, but what they do share is a mood of unmoored, ethereal uncertainty – each record really sounds like it was conceived and made on another planet – regarding their place in any world (not just this one) and how they react and respond to the subtexts of love. It is, for instance, clear that “The Mountains That You Climb,” track one on The Soul That Sighs with its ominous whistling motif (“Face On Breast”!), is thematically both a sequel to “Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go” – one of us is going out, the other isn’t – and a prequel to “Spinning The Wheel.”

“McArthur’s Son” is a slightly courtlier variant on “Jesus To A Child” with its memories of dancing and its unspoken absence (“I've prayed/That you'll come back to me/Like you've never gone away”). The vertiginous rave-up of “Falling Out With The Future” is a more purposeful and directed “Star People” (it’s the “hetero-space” which really irks Mackenzie). The nightmarish “3 Gypsies In A Restaurant” is Bish Bosch-period Scott Walker making that long-threatened disco record – if only he’d lived to make it! – about Hitler and the “slaughtered thoughts near Bucharest” but delivered in a Sparks-but-with-Glenn-Gregory-on-lead-vocals manner; it could be what the protagonist of “Fastlove” hears in that remote wine bar which never gets mentioned in ES Magazine.

Yet it is the long series of patient ballads which set The Soul That Sighs in union with the best of Older. “Return To Love” is a sort of bridge spanning The Feet and The Heart; the ghost of a 1991 rave “anthem” haunts its central keyboard figure, but in a complete reverse of what normally happens in pop – a ballad retains its basic tempo but the underlying rhythm doubles up (Pet Shop Boys’ “Always On My Mind,” the “Classic Radio Mix” – or, if you’re adventurous, the nine-minute “Soul-Hex Vocal Anthem” remix – of Toni Braxton’s “Un-Break My Heart”) – the song’s dance implications are modified to accommodate the balladic form. Billy’s “Please don’t ‘show up’/Stay close enough” is his equivalent of George’s “Please don't analyse/Please just be there for me.” There’s the scarcely-contained yearning of “Give Me Time” – “Been around the world trying to find myself/And I'm not going to do it with someone else (i.e. I’m only going to do it with you).”

“And This She Knows” – the “she” may well refer to Billy’s mother, who died while these songs were being prepared – is a brief and lovely, if untouchable, “Bridge Over Troubled Water” update which indicates that mother and son are of the same mind – you wouldn’t change either of them, and this they know. Both “14 Mirrors” – a torched song, borne along by its steadily mounting air of aggravation – and “Nocturne VII,” the “record”’s unexpected counterpart to “The Strangest Thing” (unexpected because it’s so hushed) with its extended references to absenting oneself from the world – “You'll come for me/And take me by the hand/Far from all I know/You'll take me there/And I will understand” – attain rare levels of fait accompli sublimity.

The album, as such, concludes with the final nudge into complete freedom. I have known “At The Edge Of The World” since 1997, when it appeared on the posthumous Mackenzie compilation Beyond The Sun (on which six of The Soul That Sighs’ eleven songs first appeared) and it does not take long to discern the final and unfairly truncated reunion with Alan Rankine, Billy’s missing other half who always moved him one important step up the ladder to transcendence. It isn’t merely the great missing Bond theme (or maybe it’s too low-key for Bond; see also Scott Walker’s “Only Myself To Blame,” commissioned for The World Is Not Enough), or a subtle acknowledgement (via the involvement of Simon Raymonde) of the enormous debt borne to the Associates by the Cocteau Twins – Rankine produced “Peppermint Pig” and listen in particular to 1985’s “Ribbed And Veined” for early signs of the edge of a world – but Billy’s farewell to…something. A world which disappointed him, wasn’t quite good enough for him or kind enough to him. How good did it feel for to, finally, be free?

“If I think out loud, no one seems to care.”

It is at this point where we need to ask ourselves, and maybe also the world; what did New Pop do to, not just for, us? Here we have two indisputable architects of the New Pop cathedral who in their separate ways did their best to disconnect themselves from its feed. And one problem is that one of those architects was happening without the permission of the man who named the movement New Pop.

I’d pretend I didn’t know what Morley wanted from New Pop because I know exactly what he wanted; smart, quick-tongued underachievers – the Top 40 filled by disciples of Anthony Blanche. But even before he conceived a name to encompass what he desired, he was losing. He wanted the unlovable Howard Devoto at number one but please-love-me Gary Numan got there instead. He wanted Simple Minds but got Duran Duran. He so desperately desired Billy Mackenzie to be the greatest of New Pop stars but that actually turned out to be George Michael. Everybody involved in New Pop, from Martin Fry down, said George was the best out of all of them. That spiv from Bushey, snorted Morley; what an outrage! What does he know about Clock DVA or Psychic TV (in truth, quite a lot, on the quiet, but he never asked George that)?

Morley’s 1983 BLITZ interview with Wham! is embarrassingly readable. He went in expecting Modern Romance and didn’t get snappy, artful responses. It was abruptly clear that what he considered New Pop wasn’t really what New Pop was about (“I don’t think you have a grasp of basic human requirements,” a vexed Michael tells Morley, accurately). His first-year student wordplay goes nowhere. He comes out of the confrontation the worst. Eighteen months later, at the gaydar height of 1984 pop (in which, via ZTT/FGTH, he was indirectly involved – field research at the time indicates that “Relax” took so long to get going because potential record-buyers were put off by the wording of the advertisements for it), he whines at readers of the same magazine about their not appreciating a new Australian T. Rex box set or the new Pete Shelley album. He sounded like your dad.

But here’s a thing; the popularity of the Associates and Wham! didn’t overlap. In May 1982, when “Club Country” was inching its way towards the top twenty, “Wham! Rap” received the critical plaudits but not (yet) the sales. Six months later, however, “Young Guns” was flying towards the top three and the Associates were finished; Mackenzie released a curious single with “Orbidoig” (Steve Reid) called “Ice Cream Factory” which sold reasonably well in Scotland but completely flopped nationally.

By the time of Band Aid, which featured George Michael (and Wham!’s “Last Christmas” therefore meant he completed the year of 1984 in first and second places in the chart), those who were considered to have originated New Pop – not just the Associates (with which brand name Mackenzie and Reid had continued, less than successfully), but also ABC, Marc Almond and that’s just the As – had been relegated to the status of remote fringe acts, stranded in frozen outposts. Geldof had accidentally ensured that future pop developments would only be conducted among those people who had been accepted into the mainstream throng, and in the process cease being “pop” (no more frippery, outrage or funny outfits – you had to dress down, slow down and show you CARED; see also Live Aid’s mirror image Red Wedge).

Yet George Michael himself didn’t seem too thrilled by the state of things, and that steady descent from smilingly insolent frivolity became increasingly evident in his solo work. Faith remains an excellent album and Listen Without Prejudice a mildly less excellent one.

But Older saw George charmed into the cavern of somnolent solitude until his work began to resemble one of Ad Reinhardt’s black squares. It is a magnificent, etiolated dead-end but so was blackstar. And it emphasises to us, just as devoutly as the songs of The Soul That Sighs do, that believing so fervently in New Pop leaves you in a place far, far away from anybody or anything else. These two self-abandoning souls, who between them summed up and some say exceeded what New Pop was really about, and who ended up exiled from pop discourse. 1996 was full of boys jumping up and down to Oasis and girls about to jump up and down to “Wannabe.” George Michael seemed as remote from any public square as Alec Guinness’ George Smiley – for Smiley’s spectacles, see Michael’s beard – yet understood what exactly was going on only too well.

Why did both Billy and George get shut out from pop happenings? Denied a voice, deemed not very hip; whither Mackenzie’s peregrinations (“Been around the world trying to find myself,” remember?) in the age of Jarvis Cocker and Neil Hannon? When Billy and Alan cut those “Associates” demos in 1993 or thereabouts, they really couldn’t have been more out of fashion. Record company A&R people looked at them, nodded solemnly and failed to return their calls. Old men who think they still have it. How charming. It’s Brett Anderson who counts now (and yet, with steamroller-level irony, Anderson was instrumental in getting, or trying to get, Mackenzie signed to Nude Records; many say that in 1996/7 he was right on the verge of making an extremely major comeback).

As though neither was allowed to announce that New Pop had failed.

That still leaves the question of how I’m going to finish this. I can’t leave Billy in his father’s cold shed, or George in his Goring-on-Thames bedroom. Perhaps it’s best to take our leave of both of them, for now (there’s much more George to come), on that not quite desolate beach, at the edge of the world, where looking at them you couldn’t imagine in all the world that they were actually pretty happy.

Thinking again of “And This She Knows,” I am also moved to think of a song called “Run The Length Of Your Wildness” by the Los Angeles actress and model Kathe Green, recorded in London under the combined aegises of John Cameron, Wayne Bickerton and Tony Waddington in 1969. At the time Green was a very close friend of the actor and occasional singer Richard Harris (did you spot that “McArthur’s Son” reference?) who furnished the phrase “run the length of your wildness.” The song appears to be about him and his wayward ways; it’s a shame he chooses to be like that, the song concludes, but he’s happy in himself so let him carry on being “him.” In its five-and-a-quarter minutes the song sways, sometimes gently and at other times violently, between many moods and settings, though always resettles at its chorus, although each chorus is approached from a different and unexpected angle. It seems in spirit to predicate both Billy Mackenzie and George Michael – and either might have heard it on the radio at a young age. It was never too late for either of them to be what they might have been.

(Perrin screen grab from this fascinating blog)

“I can't tell them how to feel/Some get stoned, some get strange/But sooner or later, it all gets real”

(Neil Young, “Walk On,” On The Beach, 1974)

“Fuck off, Carlin. You’re mad.”

(The sixty-one-year-old George Michael who should have been, two hours ago)