(#275: 5 March

1983, 1 week; 19 March 1983, 1 week; 21 May 1983, 5 weeks; 28 January 1984, 1

week)

Track listing: Wanna

Be Startin’ Somethin’/Baby Be Mine/The Girl Is Mine (with Paul

McCartney)/Thriller/Beat It/Billie Jean/Human Nature/P.Y.T. (Pretty Young

Thing)/The Lady In My Life

Scenario 1: “OK, guys,” said Quincy Jones to his team as

they prepared to record Thriller, “we’re here to save the recording industry!”

A recording industry which – at least from an American perspective – had

singularly failed to deal with disco and punk and had been superseded by those

new-fangled video games. It is true to say that the recording industry had no

real idea what to do with disco, and one wonders how many people at the major

recording companies had even heard of punk.

Michael Jackson’s disquiet following Off The Wall is therefore understandable. Hadn’t the record at

least attempted to break down so many boundaries? But it was almost entirely

ignored at the 1980 Grammy Awards; Jackson won Best R&B Vocal Performance

(Male) for “Don’t Stop ‘Til You Get Enough” but Record of the Year went to 52nd Street by Billy Joel; “What A Fool

Believes” by the Doobie Brothers won the equivalent single award. In the same

year Jackson attempted to get Rolling

Stone interested in doing a cover feature on him but was curtly told that

black faces on the magazine’s cover meant a drastic reduction in readership

numbers.

Putting aside the idea – which remains prevalent – that

the judging panels are in the unfortunate habit of giving out Grammys to the

kind of records which don’t really get made anymore, displaying deferential

adherence to a twisted relationship between art and commerce which I’m not sure

they really understand (in 1980, “I Will Survive” won for “Best Disco

Recording,” but that award has never been given before or since), it is easy to

see why an angry Jackson should consider Off

The Wall “not good enough” and wish to top it with a record which nobody

could ignore, which had to be played and, more importantly, loved everywhere.

Whatever “loved” meant.

Scenario 2: Rod Temperton in his hotel room, thinking of

a title for what will be the title track of the new Michael Jackson album.

Temperton has freely admitted that he hates writing lyrics, that it’s his least

favourite part of songwriting, but he couldn’t quite get this one right.

“Starlight”? “Midnight Man”? He fills a notepad with some four hundred possible

titles, but none clicks, none has that extra-special factor that will make

people take notice. So he sleeps on it and awakens the next morning; a

metaphorical ray of light strikes him – of course! “Thriller”! It’s so simple,

so directly communicative – and he thinks how everyone will clean up on the

merchandise that will follow in its wake.

And so was generated the idea for Thriller, a record that would cut across customs posts of race,

creed, sexuality and musical prejudices, an album where every track was a hit,

a phenomenon whose notes and looks would be known everywhere from Timbuktu to

Vladivostok. An album whose speed and colour could compete with any video game

– even if it proved instrumental in dragging popular music down to the level of

video games.

Make no mistake; if you were, say, ten years old in 1983,

Thriller is likely to be your pop

year zero, a beginning of time as definite and irrevocable as Please Please Me a generation before.

Many informed commentators happily proceed to assess music today as though Thriller were the original ancestor;

anything before it doesn’t really communicate to younger people in the same

way, become virtual dinosaurs, the Records That Rocked Like CDs or Downloads. A

commenter on I Love Music said the

following about my reluctance to continue with Then Play Long:

“I don't feel it as keenly as MC does, because the world

of pop that it represents was largely gone, or seen as hugely old-hat, by the

time I really started listening. That world isn't mine, what it represents

isn't woven through the fabric of my understanding of pop…”

I suspect that this gets truer by the year. But if you

accept what pop music has done to us as a direct or indirect result of Thriller, then you have to recognise

that Thriller is the line in pop’s

sand, and ultimately was disastrous for pop.

After Thriller,

it seemed that just being a pop record wasn’t enough. Astute observers will

say, well, wasn’t that why the album came along in the first place – because

some snobs thought that 78s weren’t enough? And perhaps the story which this

blog has tried to tell between 1956-83 is one which can only be regarded in the

past tense. It is on the cards that albums will eventually disappear, that

people will get back into their original habit of listening to individual

songs, that these songs will transcend identity or even their recording and

become part of a generalised folklore.

But Thriller

represented the firing of the starting, or stopping, pistol. After Thriller, it was taken as read that

every pop record had to sound “big,” be an “epic,” appeal to the lost video

game generation (broadly: 12-24 years), say yes to some kind of future or

worship its own present tense. The market for small, ambiguous, complicated

low-budget records – and musicians – began to shrink, such that even in the

eighties those bravely still scouring the indie coalface could be accused as

pedalling “music for losers.” If you weren’t a winner in the age of Reagan and

Thatcher, you simply didn’t count.

Apropos the merchandise, it also became the unquestioned

case that after Thriller, pop records

no longer really existed as things in themselves; they became merely the most

prominent link in the merchandising chain, a chain which would also involve

videos, tours, T-shirts, commemoration mugs, profits being diverted away to

fund multinational arms companies. The video for “Thriller” which appeared

almost exactly a year after the album’s release set this in concrete; how many

people could listen to the record alone after seeing Jackson act out what pop

had done to him, and by extension was about to do to the rest of us?

So the stage was set for pop music whose entire field of

interest and methodology of presentation began and ended in adolescence;

shouldn’t adults be going to the cinema, or listening to jazz (although the

horrendous mid-eighties “jazz revival,” which jazz itself was lucky to survive,

demonstrated that the tentacles of Thriller

stretched out as far as, and frequently further than, they needed to have

done)?

Given the sphere of inescapable influence that the record

has had, it is, however, interesting to note that initially Thriller nearly died a death. Released

in November 1982, it was predictably swamped by the Christmas market, and was

generally reviewed scathingly. This may in large part have been due to the

still bizarre choice of a lead single: “The Girl Is Mine.” It was the first

song to be recorded for the album, back in April 1982, and a nervous Epic may

have thought that it was a play-safe option.

In the event, it proved to be too safe; although the song

reintroduced interracial love rivalry to pop for the first time since West Side Story (let’s leave Catch My Soul out of this for now), it

was a bland broth; as McCartney swapped good-natured Radio 2-friendly

platitudes with Jackson over a neutralised soundtrack, it was hard to credit

that this was the same man responsible for “Penny Lane” and “Helter Skelter.”

Observers and fans saw the record as a sellout to whitey; in Britain the

single, which was not accompanied by a video, rose in kneejerk fashion from 33

to 9 before people suddenly did a doubletake, say “hold on; what IS this

shit?”; the record climbed just one place higher before falling back

precipitously and dropping out of the Top 75 altogether after barely two

months.

And Thriller,

upon its release, was slammed. This was no Off

The Wall; gone was the easy charm of “Rock With You,” the dervish intensity

of “Don’t Stop.” In their place was – what?

A jagged, snarling, paranoid “Don’t Stop” wannabe (startin’ somethin’) clone.

And “Baby Be Mine” was nice but no “Rock With You,” not by the longest of

chalks. Furthermore, what was it with all those hammy guest stars – Eddie Van

Halen? Vincent Price? Had Off The Wall

needed any of that?

It was regarded as a major disappointment, and thus its initial commercial progress was relatively muted. It looked set

to be the season’s, if not the year’s, if not the decade’s, most expensive

flop. Then came the single of “Billie Jean,” and the slow

turnaround, and then the video, and then Motown

25, and then suddenly Michael Jackson had clambered, or surfed, onto the

top of the whole pop heap, for better or worse (ours and his). The irony about

such a superficially unassuming record like Thriller

pulling it off is that it was clearly a transitional piece of work; about half

the record looks back, warmly and lushly, at the seventies and Off The Wall and is, in that regard,

deeply conservative and consolidatory. The other half looks radically and

remorselessly at the future, with songs built on rhythm first and melody

second, and overall a far more brutal rhythmic tow. All of that other half was

based on songs written by Michael Jackson; he also wrote “The Girl Is Mine,”

perhaps as a desperate wave back at what he once was, and clearly with

McCartney’s “Girlfriend” – which he had performed on Off The Wall – in mind, but on the album sleeve the lyrics to the

latter are accompanied by a deeply disturbing drawing by Jackson of McCartney

and himself, both grimacing and playing tug of war with a screaming woman

caught in mid-air between them; the entire upper half of her head is invisible,

such that one cannot tell whether she is horrified by or laughing at the act of

being pulled apart (she’s stuck in the middle, and her pain is thunder).

In addition, Jackson’s lyrics were anything but

reassuring. “Wanna Be Startin’

Somethin’” is, on its surface, a retread of “Don’t Stop,” but where the

latter’s groove grooved, so to speak, fluid and natural, this song’s beats and

propulsion are all gritted-teeth aggressive, ruthless, jittery, agitated.

“Don’t Stop”’s naïve Star Wars

foreplay is replaced by an extended “Soul Makossa” climax – where “Don’t Stop”

steadily atomised to its essence, “Startin’ Somethin’” adds more or more, even

if what is being added is mostly padding. David Williams’ midsong rapid-fire

descending guitar lines are technically impressive but impassive; the listener

does not necessarily get the feeling that these are being played by a human

being.

Meanwhile, Jackson sings of rumours, harassment, the

sudden absence of fun involved in being a pop star and the attendant paranoia.

Billie Jean is introduced in the third verse almost as a joke – the song’s real

intent is to set the stage for the rest of the record – and Jackson’s

mock-exasperations (“They said she had a BREAK-down!”) uncannily presage Robin

Thicke’s “Tried to do-MESTICATE you!” of three decades hence. But then there

are bland homilies from the Reagan Book of Uncommon Prayer – “If you can’t feed

your baby! Then don’t have a BABY!” – which in part seem to mask the

possibility that the cause of Jackson’s suffering is an actual, rather than

metaphorical, baby, or else that the “baby” is his own soul, slowly dying.

But why the “Soul Makossa” turnaround at the end? Why, in

that case, “Soul Makossa”? It has been cited as one of those records which, by

accident or design, causes history to be rewritten or redefined or clarified;

and yet Manu Dibango wrote and recorded the song as a B-side for a promotional

single about the Cameroon national football team (“Mouvement Ewondo”). Still,

it is fortunate coincidence that the DJ David Mancuso chanced upon a copy in a

West Indian record shop in Brooklyn, began spinning it at The Loft and, well,

started something, as well as demonstrating how closely James Brown’s thing

echoed the multitextural rhythm-upwards propulsions of African music. Did it start

“disco”? Whether it did or not, its existence, discovery and projection –

within weeks of Mancuso playing the record at The Loft, at least two dozen

cover versions hit the streets – meant that an awful lot of music which

wouldn’t have happened without it, including the solo work of Michael Jackson

from 1979 onwards, happened.

As the chant spreads, Jackson presents a Spartacus-like

picture of defiance: “Lift your head up HIGH!/And scream out TO THE WORLD!/I

know I am SOMEONE!/And let the truth UNFURL!” A little later, he asks: “Yes, I

believe in me/So, you believe in you?” Or perhaps it’s an instruction: “So –

you believe in YOU!” And the song lifts itself out of its singer’s morass, even

if only temporarily.

Temperton’s “Baby Me Mine” indeed is no “Rock With You”

but is pleasant enough in a backward-looking way; there’s a lovely little

cross-channel tingle of string synthesiser notes falling like icicles from

neglected December curtains over the line: “I guess it’s still you thrill me” –

five people are credited with synthesiser on the song but Temperton did the

arrangement. Then on the album comes “The Girl Is Mine,” which is forgotten as

soon as, or before, the song disappears.

Side one concludes with the title track, which really is

a rather traditional song under its Great Pumpkin deelyboppers; the spectre of

“Boogie Nights” haunts the entire piece, but what is more haunting, to the

point of being profoundly disturbing, is Jackson’s calmly demented vocal. We

already received notice on “Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’” that something wasn’t

quite right in MJ’s world – all 362 seconds of that song exist to disrupt and

unnerve the listener – since besides the gossip note-taking and the “We Are

Soul Makossa’s World” shoutouts, there are words, buried in the mix, like

“You’re a vegetable…Still they hate you…You’re just a buffet…,” sung in as

frightening and distorted a procession of voices as any that could be found on

the Butthole Surfers’ Locust Abortion

Technician half a decade hence; a strangulated gasp-cum-umbilical cord

cackle which reminds us at at the time of Thriller

Jackson also recorded and narrated a children’s storybook adaptation of the

film E.T.; on his projections here,

the sounds more powerfully resemble the voices buried within the television set

on that other side of the E.T. coin, Poltergeist, than any amiable mongrelisation of Carl

Sandburg and Debra Winger.

But the entirety of Jackson’s vocal performance on

“Thriller,” the song, is designed to give the listener nightmares, and not the

commoner or more expected ones either. Every fibre of Jackson’s larynx, lips

and teeth are dedicated to the highest possible intensity of delivery, such as

those gasping and grunting tics, hitherto punctuation marks as natural as

Lester Young’s periodic play-your-own-bassline tenor sax honks, now become

atoms of oxygen, things he needs to do in order to stay alive.

And what exactly is Jackson proposing in “Thriller”? Why

precisely is he making his partner sit down and be scared witless by a horror

movie on TV? As written by Temperton, the lyrics are comic book ticksheet hokum

worthy only of Bobby “Boris” Pickett on an off day. But as sung by Jackson, the

words become creepier, more painful, more fascistic. It is as if he is chasing

his lover – if his lover she be – around the house, promising her the

apocalypse with the grimmest of smiles. He systematically locks all escape

routes and positively chuckles in triumph when he reaches “There’s no escape

from the jaws of the alien THIS TIME! (his own backing vocals: “They’re open

wide!”)/This is the END of your LI-IFE! WHOOOOHH!!”

“I mean, white Reaganite fuckers,” he appears to be

implying, “I’m just going to EAT your fucking WORLD and get my REVENGE!”

Then the remote control and the collective huddle on the

sofa, and the song slowly backs off from its own implications. To a point,

anyway; Vincent Price got the job because he was a friend of Quincy Jones’ then

wife, the actress Peggy Lipton, who recommended him. He was by all accounts an

absolute gentleman, and did his work in two takes. There was a second verse of

his “rap” which was omitted from the final recording but can be found as a

bonus track on the Thriller: Special

Edition CD.

But in any case, Price performs what is actually an

extremely corny sequence of lyrics with the straightest of faces; this

cultured, affable and palpably harmless man, a former member of Welles’ Mercury

Theatre and long-standing art adviser to Sears Roebuck, knew that he was boss of the shallowest genre in

cinema, and that his position was borne out of a paradoxical goodness of heart

multiplied, or divided, by disillusion with what little forties Hollywood could

find to do with him (hence his breakthrough role in House Of Wax was a reaction against always being seventh on the

cast list). So he needs do little on “Thriller” other than intone some

off-the-peg horror nonsense as though it were The Last Trump and bury pop with

his Number 2 cackle.

It was enough, though, and a year later the song’s video

appeared with an even more sinister subtext; now all of pop’s audience were

doomed only to be eye-dead zombies, looking, dressing, dancing and breathing

the same as their steel cube of idolatry which on closer inspection was made of

the purest paper. Jackson’s werewolf glance back at the camera at the end of

the video suggested that there was no turning back; I am pop’s future, shrink

back and go back to jazz.

Side two begins with chimes of doom; not the Dies Irae

but a Synclavier, possibly sampled (actually played live by Tom Bahler but

adapted from a 1981 demonstration record entitled The Incredible Sounds Of Synclavier II). Then drum machine and

drumkit enter sequentially, and not quite locked together; for the record’s

token rock song, “Beat It”’s beats never quite beat – there is a sideways

shuffle surprisingly reminiscent of Slade. Jones was reportedly looking for

something in the ballpark of The Knack’s “My Sharona,” although Devo’s “Whip

It” and especially “Let It Whip” by the Dazz Band are more readily called to

mind.

But, once again, the desperate urgency of Jackson’s

performance overrides any need to resolve gang wars (despite Jackson casting

members of rival L.A. gangs the Crips and the Bloods to perform in the video)

or get black music on MTV; this seems to be about more than just

run-for-your-life-Tony stuff. As Jackson sings lines like “They’ll kick you and

they’ll beat you and they’ll tell you it’s fair,” the spectre of his own father

springs much more readily to mind; the real source of his pain, the reason why

he kept having to run away, escape and change. Jackson raps on the side of a

drum case with a beater, and Eddie Van Halen solos (remember, Van Halen is what

most of late seventies America had instead of punk). Oddly, his solo, played

with what music writers tend to label as “commendable gusto,” is the antithesis

of the macho moves being played out around it, suggests that there is more to

rock than waving one’s plectrum.

Then there is “Billie Jean,” the principal reason this

record is what it is, and the horrific hall of mirrors at the centre of the

labyrinth, where pop is forced to look at itself, and doesn’t like what it is

being made to see.

To put it plainly, this isn’t something you would have

expected from Donny Osmond.

The voice of a weekday morning Radio 1 DJ, early 1983,

playing “Billie Jean” just before it becomes a big hit: “Give it a chance. It’s

a grower.”

A twenty-five second intro, and Jones didn’t want that;

too long, Michael, you’ll alienate people, you’ve got to give it to them on the

nail.

You don’t understand, Quincy, he replies, I want to go

somewhere new. It’s good for segueing at discos. What’s wrong with disco music

anyway?

And what about

Marvin?

Twenty-five seconds, twice as long as the introduction to

Gaye’s “Grapevine,” although even that was considered audacious in its day.

On the full album version of the Temptations’ “Papa Was A

Rolling Stone,” it’s a good three-and-a-half minutes before Dennis Edwards remembers, remembers, the third of September.

“Billie Jean” – unimaginable, of course, without Norman

Whitfield setting the precedents; not just of space and the beat, beat, beat of

that drum, but also the stoked-up, possibly unfounded paranoia.

The child is turning into an adult, and doesn’t like it.

All the spring and bounce of “Don’t Stop ‘Til You Get Enough” has solidified

into an air of petrified wariness. The ceaseless multirhythmic matrix remains

in “Billie Jean” but now the rhythms and guttural punctuation whoops are all

tensed, coiled, hunched into its thin, turned-up lapels. Whereas Jackson

previously yelled out of exultation, now his gasps tremble in their own dread.

Now the jagged guitar lines and cross-cutting percussion are like surfing

barbed wire rather than waves of passion.

But it was those waves of passion which led Jackson into

his own shadow; here he is being pursued by someone whose child may or may not

be his – and the tension is made uncomfortable (and therefore generated) by the

knowledge that, despite his would-be assertive denials in the chorus, he

suspects that he is likely to be the father; witness the anguished howl of

“People always told me, be careful what you do!” or the quivering “oh no” which

responds to “his eyes were like mine.” He is shitting himself.

The surface, however, has to stay as smooth as possible;

he moonwalks perhaps to avoid his bowels and bile spilling out onto the video’s

neon Yellow Brick Road; a video directed by the same man who directed the video

for “Don’t You Want Me.” Dancing only with himself, and maybe only for himself.

Jeffrey Daniel may have moonwalked first, and taught

Jackson how to moonwalk; the important thing was that it was Michael who was

doing the moonwalking, on a corny variety commemorative TV show which Berry

Gordy practically had to beg him to do. Suddenly he floated on the stage, and

the rest of show business ceased to exist.

On a musical level, despite Jones’ sublime deployment of

space and echo – and the string synth exclamation marks in the second and third

choruses may betray an early Lexicon Of

Love acknowledgement – “Billie Jean” is maybe the blackest of all Jackson’s

number ones, and in all senses; its circumferential catwalk of a bassline, its

forceful, decisive, dead-on beat, its recoiling handclaps present a new dynamic

to pop sonics, but its primeval fear…and that tom-tom beat, buried amid the

gloss but still at the song’s centre…connect it directly to “Grapevine.” In

addition, Jackson’s glaring, epileptic, wracked vocal is an exemplary portrait

of someone on the crown point of falling apart.

It was one of the best pop singles of any era, almost

certainly the best pop single of its year, and yet as a pop record it too

helped to bury pop.

Why? Because where

could pop have gone after this? What was left for it, when its rotten,

corrupt, vicious, villainous centre was exposed so fully and pitilessly? It is

as if Jackson is not just griping out a shaggy dog story about a groupie, but

that he is holding all of pop culture to the hammer. These songs about undying

love and undiluted passion for people whose ages rhyme easily, the very

material of fandom, the point where it leaps off the bridge and transmutates

into destructive worship…

…what do they all mean, what was it all worth, as Bardem’s

executioner asks Harrelson’s bounty hunter in No Country For Old Men, if this

is where it gets you?

You want to be a pop star? Good luck. Look at your

predecessors, and how badly they did. This is where it gets you…

…because the baby might be yours.

…because the baby might exist.

…because IT IS ONLY HAPPENING IN THE TWISTED MIND YOU

ONLY HEAR AT NIGHT. When you’re not lying nervously in bed, waiting for your

father to clamber in through the open window in full ghost costume and scare

you forever, making sure you’ll never be an adult…

We love you. OMG, we love you so much we want to BE you,

tear you limb from limb if we have to because that’s how much we LOVE you…

I mean, why do you think Elvis retreated into

security-sedated seclusion? Read the accounts of those early hayride/state fair

tours and there were always pissed-off boyfriends looking to start a fight,

idolising would-be lovers prepared to tear the skin off his back, never mind

his shirt, strip down his car to find…what? He put up the screens just so that

he could continue living, even if only for another couple of decades.

Because, with “Billie Jean,” pop hit a sudden but

definite dead end. Somebody else was turning it around and showing the

playground to have been a sham all along. A music based on being

non-conformist, about being dirty and deviant and stinking and impolite…well,

what if all of that turned out to be true?

What if pop was just a ghastly half-century of a mistake?

An aberration, something to be swept under the dust covers of history in a few

centuries’ time.

King of Pop, huh? Go ahead, Mike – you want to be the

King of THIS?

She says the baby is yours. But you know that in order to

become a father, to help beget and raise a family, you have to be an ADULT?

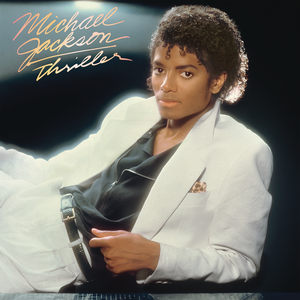

On the cover of Thriller

When Michael was nine, his father

Michael is reclining, in a white suit with black shirt,

black belt and a yellow/red handkerchief in the breast pocket of his jacket. He

looks slightly amused, more than a little sardonic – black or white, male or

female, who from a visiting planet could tell?

On the frontispiece of Thriller: Special Edition he is in nearly the same pose but he is

up, grinning a sickly grin, holding up a tiger cub as though he were holding it

hostage. He thinks he’s pleasing everybody, providing entertainment for the

whole family.

Maybe that’s what pop thought it was doing all along.

But “Billie Jean” suggests that pop may only ever have

been an evil lie.

And what are adults doing listening to, or writing about,

pop music anyway? Shouldn’t they be going to the cinema, or listening to jazz?

The cinema; the video store, which came into being almost

entirely because of the The Making Of

Thriller video. Thirty years ago pre-recorded videotapes were generally

still too expensive to buy. But the Thriller

video proved so popular that people who couldn’t afford to buy it wanted to

rent it out. And so entire industries came into being because of Thriller. No bad thing, of course – but what

happens when things move on, when tastes or technology change?

But it was like – if you’re an adult, Thriller isn’t really for you. Not really.

(And there’s this theory, still quite popular, that “Thriller,”

both song and video, are allegories about coming out; but I’d be surprised if

Jackson ever knew what a closet looked like, apart from being somewhere to hide

from his father.)

And it turned out to be like – if you’re an adult, pop

music from now on won’t really be for you. Not really.

And then…things go quiet, just as they did on the second

side of Off The Wall. The stuff like “I

Can’t Help It” and “It’s The Falling In Love” which personally I would have

been happy if Jackson had kept on doing.

Because it’s when things go quiet that a realer Michael Jackson, a more tactile

Peter Pan, emerges.

“Human Nature,” one of the loveliest songs on the record,

meditative, encyclopaedic, a song of the night as liquid and truthful as John

Martyn’s “Small Hours,” a chord sequence Miles loved enough to record his own

version…

…or so it would seem, because the song’s actually about a

nocturnal urban stalker, looking for a girl (“She likes the way I stare,” sung

as wistfully and painfully as once he sang about one day in your life), acting

like a less comedic George Hamilton vampire (“Then let me take a bite”), almost

sobbing with self-pity at times. “If they say why? Why?/Tell them that it’s

human nature.” Why WHAT, Michael? What have you done? “I like lovin’ this way,”

and, just before that, “Why, why, does HE do me that way?”

But the song’s final verse finds him in the morning after;

they are lying together, he is awake and already impatient: “Reaching out/I

touch her shoulder/I’m dreaming of the Street.” The song fades on the saddest

closing chord since “Dreams.” The

reverie has changed nothing, and does not put the uncertain heart at ease.

Then there is the placid

bubblegum of “P.Y.T.” which slips by as though having been outtaken from The Dude, and finally, my favourite song

on the record (and also, almost certainly, its least known and least played

song), Temperton’s “The Lady In My Life” – it is as though the nightmare played

out throughout the rest of the record has been dreamed, and the awakener has

awakened, and somewhere it is still the seventies, always and forever. A

wonderful ballad with a divine chord sequence to which I could listen forever

(as well as paving the way for Erykha Badu, Jill Scott etc.), Jackson sings

simply, and elegantly, and beautifully, about moments in love (although the

album’s dedication – “lovingly dedicated” - may suggest that Jackson may in

part be thinking about his mother). Like “Thriller,” the two of them are alone

at night; unlike “Thriller,” there are no televisual horror demons lurking. As

if this is how it has always been; if only Michael Jackson could always have

been like this – when the song is finished, as such, Jackson takes off into a

bliss-laden sequence of abstract slow-motion scat-singing, and we think not

just of Miles and Coltrane, but of an unlikely counterpart; Elizabeth Frazer of

the Cocteau Twins. Or perhaps not so unlikely, since, like Frazer, Jackson’s

voice, at its best, frequently works as an instrumental voice, the words not

always decipherable, but the emotions always clear.

And yet Thriller was the beginning of the end of pop’s life. As I hope I

have demonstrated, what the record set in motion is not necessarily its fault –

the adjective I could best use to describe Thriller

would be “tentative.” It wants to be new, but at the same time is careful not

to cast old Jackson fans aside. With a couple of exceptions, I do not believe

it to be a great album. When it returned for the last time to number one in

early 1984, in the wake of the “Thriller” video, listening to it was like

playing PacMan, whizzing by as it did with hit after hit. But then again, why

not just play PacMan? What happened after Thriller

is, as far as I am concerned, the route down the other side of the hill. It was,

and is, a disaster in which not even the artist who recorded Thriller could be saved, or save

himself. I thought long and hard about writing this piece – is it better to

tackle demons head on or avoid them altogether, for there are many demons now

to come in this tale? The statistics are there to be found – to date, Thriller’s estimated worldwide sales

range between 51-65 million. In the USA, it has sold 29 million units, and its

place as the all-time best-selling album there is subject to a regular

tug-of-war with the Eagles’ Their

Greatest Hits (1971-1975). If you believe what Greil Marcus has to say

about Jackson, then Thriller marks

the point where the pop star, rebel or otherwise, transmutates not into a god,

but a commodity for compliant consumers existing in a world which fundamentally

hates them. The thing around the thing, rather than the thing itself. And now,

an exhibit on the ground floor of the museum to be glanced at with brief, bored

respect before going upstairs to the colourful, loud, interactive features

which will continue to interact in loud colours long after there have ceased to

be people with whom it could interact.

On Thriller: Special Edition there is a bonus track of an unused song

from the Thriller sessions entitled “Carousel.”

It is among the most sheerly haunted of Michael Jackson songs, about a circus

girl who ran away – or did she? “I’m from a world/Of disappointments and

confusions” he sings, and later, after she’s gone, he ponders, chillingly: “What

I can’t recall/Is if there was a girl at

all/Or was it just my imagination?”

Running away with the circus

girl. I wonder if Vincent Price ever saw Wings

Of Desire, heard the words about “I’m an old man with a broken voice, but

the tale still rises from the depths” and wondered sometimes about Michael

Jackson.