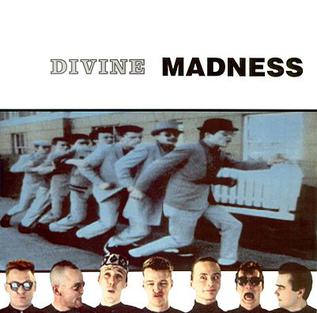

(#444: 14 March 1992, 3 weeks)

Track listing: The Prince/One Step Beyond/My Girl/Night Boat To Cairo/Baggy Trousers/Embarrassment/The Return Of The Los Palmas 7/Grey Day/Shut Up/It Must Be Love/Cardiac Arrest/House Of Fun/Driving In My Car/Our House/Tomorrow’s Just Another Day/Wings Of A Dove/The Sun And The Rain/Michael Caine/One Better Day/Yesterday’s Men/Uncle Sam/(Waiting For The) Ghost Train

We recently watched Patrick Keiller’s documentary, or filmed psychogeographic meditation, London, which with infinite patience presents us with a portrait of the city as it existed, and perhaps slowly mutated, throughout the year of 1992. Narrated by an unseen Paul Scofield, the film tells of the experiences of his (also unseen) friend Robinson, who has just returned to London from abroad – the strong implication is that this is Robinson Crusoe – and his incremental dismay at the decay into which the city is slowly collapsing. The era of Thatcher was over, but nobody seemed to want to let go of it.

One particularly hypnotic and instructive sequence occurs when Keiller’s camera records a mass of commuters, disembarking from the train at London Bridge station (as was), expressionless yet quietly determined, heading over the bridge towards the City and their jobs, mainly consisting of making lots of money for other people. What are they thinking or dreaming? Do they think or dream, or have they simply given up life for the sake of existing?

There was a General Election in the spring of 1992, and for most of its run-up, the Labour Party, under Neil Kinnock, looked to be at least marginally ahead in polls. There was a swing from the Conservatives to Labour which reduced the former’s parliamentary majority from 102 seats to 21 – but the Tories still won. One could generously suggest that many felt the new boy John Major deserved a fair chance – after all, he wasn’t anything like Thatcher – but, as Keiller makes Robinson say, the real, melancholy reason for the Conservatives’ victory was that, as push came to shove, the middle classes, bound down by historical Protestant work ethics and imbued guilt and, as a result of what occurred in the France of 1789, a morbid fear of socialism, could not bring themselves to vote for a socialist party. Thus the country, and therefore its capital city, was about to get worse and cheaper – and so much of Keiller’s commentary is still depressingly relevant today.

Part of the optimism about a likely win for Kinnock’s Labour could be summarised by the presence of Divine Madness at the top of the charts during the run-up to the election. I would add that this was the first of ten compilation albums to make number one in Britain throughout 1992. Why the sudden craze? Perhaps some astute record companies had noted what had happened with Eurythmics, Paul Young and Queen the year before – not to mention David Bowie and the Carpenters in the preceding year - and realised there was some money to be made here.

But there was also the steady realisation on the part of a sizeable quantity of music lovers that they weren’t the people they used to be. They were approaching, or had attained, middle age. They were somewhat afraid of what lay ahead and what was surrounding them, including a singles chart which filled them with incomprehension and loathing. They couldn’t, or wouldn’t, understand this new music, and so they retreated to the music that they recognised and loved, the songs with which they had grown up. It was Rob Fleming angst two years before High Fidelity was published (and explains exactly why that book touched such a raw nerve in that same audience).

All that having been said, one wonders with some bafflement at the prospect of people listening to the twenty songs on Divine Madness and expecting a good time. I wrote over seven years ago about their first hits compilation, released a decade earlier; it coincided with the apex of New Pop and its cheery colourfulness made perfect sense in that setting. But Divine Madness is cumulatively one of the bleakest records Then Play Long has yet tackled.

No doubt many were, and continue to be, blindsided by the band’s “nutty” image, as especially presented in their videos. But, as I said about Complete Madness, this is the kind of nuttiness that might get its perpetrator locked up. It also has to be said that Divine Madness is by far the better of the two sets; it is obviously more complete and harbours no ambition other than to present twenty hits in strict chronological charting order – they actually had twenty-one hits between 1979-86 (see? It already resembled a time capsule) but the Scritti Politti cover is absent, presumably because it couldn’t be fitted into the running time of a CD.

Moreover, the hits replicated from Complete Madness are fuller here. “The Prince” is the longer and more concentrated album version rather than the original 2-Tone single, “One Step Beyond” has the unedited Chas Smash spoken introduction, “Cardiac Arrest” is also the album version, with its appropriately grim coda, and, best of all, “Shut Up” is represented in its full-length glory, complete with Mike Barson’s exquisitely florid piano which makes you wonder whether the credit was a misprint and it was really Mike Garson playing.

The notion that Madness were some kind of ska band doesn’t really persist beyond the first two singles (though clearly permeates the likes of “Night Boat To Cairo” and “Baggy Trousers”). They became one of Britain’s greatest and most heartfelt singles acts – but I think that, fundamentally, Madness was a chummy and partially slapstick evolution of art-rock. Note Chris Foreman’s furious guitar downstrokes on “The Prince,” straight out of the Phil Manzanera book of sound effects. Also “One Step Beyond” is just a little too frantic to be comfortable; at its semi-chaotic end the song sounds ready to explode.

On “My Girl,” Suggs resembles Robert Wyatt – this will be a recurrent characteristic of his vocal grain – singing an Anthony Newley song about somebody who’s angry and/or fed up with the hapless, or possibly feckless, protagonist. Then came the move into character studies, mostly based on the band’s own experiences – the numbing Motown beat of “Embarrassment,” for instance, masks a song written, mainly by saxophonist Lee Thompson, about his sister becoming pregnant and carrying a black man’s child, and outlines prejudices which are sadly still relevant in the broken Britain of late 2020.

There is very little actual happiness in Madness’ work. “Baggy Trousers” might superficially sound like a jolly romp – Suggs wrote it in part as a comprehensive school rebuff to “Another Brick In The Wall (Part II)” – but actually describes a fairly lousy childhood, and the singer’s attempts at selective or revisional amnesia. They seem at their happiest when either covering somebody else’s song – though the video for “It Must Be Love” begins with the band standing at a graveside (“I never thought I’d miss you/Half as much…as I do”) – or when words are not really needed, as per the sneakily evocative (and quite Jerry Dammers-esque) “Return Of The Los Palmas 7,” which here appears in its album form, with additional dialogue (it isn’t just “Waiter!”), and, perhaps more crucially, won over the Radio 2 audience.

But if Madness are anything, it is political, and they embarked on a remarkable sequence of singles which outlined the Thatcherite tragedy from different angles – “Grey Day” (in which the two words are never sung together) depicts a homeless and possibly mentally-wrecked societal reject desperate to stop existing. “Shut Up” (in which the two words are never sung at all; they appeared in an excised third verse) has the petty criminal blaming everybody and everything else – after all, isn’t what he’s doing free enterprise taken to its logical limits? “Cardiac Arrest” illustrates what happens to the needlessly loyal servants of capitalism when they forget to live. Side one of Divine Madness concludes with their only number one single, “House Of Fun” (although this version fades out naturally, rather than concluding with a fairground organ coda), a song which is, again appropriately, to do with coming of age and the already crushing obligation to social decorum – the lad wants contraceptives but cannot bear to call them as such. The old ladies would see and hear him and tut their imagined disapproval.

The observant listener will already have noted that in their general jerky harmonic and rhythmic discontinuity, many of Madness’ songs would not musically be out of place if played by, say, Hatfield and the North, or even Henry Cow. Perhaps their “It Must Be Love” might be viewed as a pre-emptive tribute to Cornelius Cardew – for Madness represented the (sur)real “people’s music.” I’d have loved to hear them tackle “Smash The Social Contract.”

Yet their songs never, ever mock or pity their subjects. The cheerful eejit who sings “Driving In My Car” – which sounds lightweight, but probably still carries a political allegory (Ford Mondeo Man and all that) – is characterised but not patronised (and the song’s whole tone descents recall the coda of Wyatt’s “A Last Straw”). Meanwhile, “Our House” – the one song of theirs which crossed over to America – is a celebratory requiem; the memories are preserved although the song’s consistent and insistent use of the past tense clearly indicate that the house is not. David Bedford’s strings rise to provide a blanket of mourning over the final reprise of the song’s first verse before dissolving into a poignant, sustained high A note, like the sun setting on the world. I note the passing “Moon River” reference (“two dreamers”) which would certainly have struck a deep chord in American audiences.

“Tomorrow’s Just Another Day,” complete with muted trumpet cameo by Henry Lowther (David Bedford, formerly of Kevin Ayers and the Whole World, is a constant arranging present, so this all points towards Canterbury), is probably the nearest thing here stylistically to that other mournful north London musical observer, Ray Davies. After thar, “Wings Of A Dove,” an upbeat, stop-start Carnival dream involving steel bands and gospel choirs, chiefly sung by Chas Smash and a very big hit in its own right, feels like all the sun in the world finally being let into the greyest of rooms.

Some of that new light flickers very briefly; “The Sun And The Rain” perhaps revisits the protagonist of “Grey Day” but he is now more optimistic and hopeful, if only marginally so. Set against that, “Michael Caine” (this album’s version concludes with a brief snippet of studio chat from Sir Michael himself) is about the dislocation of an informer during the Northern Irish Troubles, to Prisoner-level “who am I?” levels of paranoia. He’s never going to be let out of the Village.

So much of what Madness do is specifically London-centric; they hardly venture outside the city. Yet their deepest work speaks to everyone. “One Better Day” is a remarkable song which makes me think they might collectively be pop’s Alan Bennett – the same Camden Town setting, the same refusal to condemn or make fun of their subjects. The old lady with the million plastic bags might well be Bennett’s “Lady In The Van” (I’m not sure that it isn’t) and yet, when she and the homeless old man finally come together, it is very moving (the strings swell up) and almost a happy ending. Moreover, it anticipates what the likes of Saint Etienne would subsequently achieve with their own character studies (I can imagine Sarah Cracknell singing this song, actually).

“Yesterday’s Men” is perhaps even more affecting; Barson was already gone, and what happens now? The refrain of “Will we be here in the long run?” is chilling and, again, very grimly timely today, and probably can only be best understood when you get to my time of life. And if Suggs sounds like anyone on this song – or, let’s face it, they sound like Suggs – it is, of all logical people, Damon Albarn (the sons would have fitted perfectly on entry #605).

Finally, the politics predominate. “Uncle Sam” is nominally about World War II but is really about Reagan’s distortion of America (and is also a rather macabre, mocking distortion of their “Nutty Boys” musical setting), while their (then) farewell single, “(Waiting For The) Ghost Train” is an ominous end-of-everything apartheid allegory (“It’s black and white”) though suggests that it might also be the beginning of everything better.

The album did so well that the band thought that they might get together again for gigs. Those went well – or at least up to a point (see entry #457, which roughly coincided with their “Madstock” weekend of performances) – such that they eventually reformed properly and recorded, and indeed continue to record, several excellent albums of new material. Divine Madness brought the band back from a literal limbo. Of the remaining nine compilations to make number one in 1992 – three British, four American, one Australian and one (importantly) Swedish – we will see whether revivals generally led to rebirths. Madness, however; so exotic, yet so homemade, as Patrick Keiller might have said.