(#158: 30 August 1975, 5 weeks; 11 October 1975, 2 weeks)

Track listing: Three Time Loser/Alright For An Hour/All In The Name Of Rock ‘N’ Roll/Drift Away/Stone Cold Sober/I Don’t Want To Talk About It/It’s Not The Spotlight/This Old Heart Of Mine/Still Love You/Sailing

The thing most immediately noticeable when one looks at the inner sleeve of Atlantic Crossing is the huge, dark, blank space. At the foot, in some kind of Art Deco typography, are listed the credits; a long, impersonal list which doesn’t even bother to tell you who plays on what (a situation, I regret to report, not rectified by 2009’s 2CD deluxe reissue). There is, provocatively, no matiness whatsoever; no photos of Rod goofing around with the musicians, no self-deprecating, self-penned sleevenote…and certainly none of the musicians who had contributed to his British records. Make no mistake; Atlantic Crossing stands, or was made to stand, for a complete break with the past, the putting away of childish things and the assumption of a new seriousness.

This was understandable in the circumstances – Stewart’s solo contract with Mercury had expired and he was now fully signed to Warner Brothers; he had fallen in love with Britt Ekland; he didn’t fancy having to pay 83 per cent top rate income tax, so decamped from London to Los Angeles – but this did not stop, indeed may even have encouraged, some of the worst and most damning reviews of a rock album I can remember. Their gist was the same: Our Rod has sold out, he has ditched the Faces for anonymous, shiny sessionmen, he is a traitor to his own art, he has stopped being Our Rod and turned himself into Rod Stewart plc, an international brand for anonymous hotel lobbies and airport lounges the world over. He has become a decadent.

The facts, as usual, lie somewhere in between, and since it is not the job of this blog to recycle received wisdom but to assess fairly what is in front of it, the facts here may prove helpful. When Stewart left for the States and commenced preparatory work on his new album, he did not intend to abandon the Faces, indeed was contractually bound to do one more tour with them. But Stewart and producer Tom Dowd listened attentively to them in LA, at work in the studio, for an hour before regretfully agreeing that they could not provide a suitable backdrop to the kind of music he wanted to make. Moreover, Stewart did ask his old songwriting foil Martin Quittenton to make the journey with him and help write some of the new songs, but since this would have entailed being on the road with the Faces, the mild-mannered Quittenton settled for a quiet life.

Not unnaturally, this long-standing fan of Stax and Atlantic wanted to avail himself of the best musicians he could find. He met up with the MGs (if not Booker T) and got on well enough with them, although none of their initial collaborations made it to the final cut (they appear on the second CD of the 2009 reissue, including a scorching reading of the Bee Gees’ “To Love Somebody”) and there is no track where all the MGs appear together. Hence the sessions with Muscle Shoals’ finest, at the Hi studios in Memphis, and also in New York, LA and Miami, all with first division American session musicians (drummer Nigel Olsson, on loan from Elton John’s band, is the only other Brit to appear). The notion was not to make the album a series of soundalike tracks, but the central problem here had nothing to do with geographical disparities.

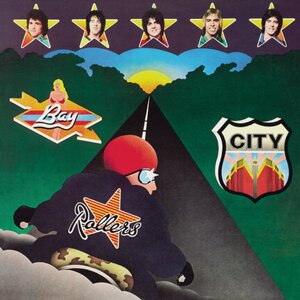

On the advice of his then manager Billy Gaff, Stewart divided Atlantic Crossing into two halves, a “Fast Side” and a “Slow Side,” and it is on the “Fast Side” that the album’s shortcomings become apparent. The symbolism of the cover was clear; Stewart has one platformed foot placed in the New World, but he is looking backwards at the Old Country, and more significantly has one foot still on British ground. True, he couldn’t have stayed with a formula which had outstayed its welcome; Smiler really had been the last hurrah for that method of working, and although it sold well enough to get to number one in the UK (and therefore into this tale), it only stayed on the album chart for twenty weeks, compared to the eighty-one weeks racked up by Every Picture Tells A Story.

But when “Three Time Loser” gets into its stride, you can’t help wondering whether Rod wants to have his cake and eat it. Yet another Jack-the-lad (or Rod-the-Mod) shaggy dog story (this time about venereal disease), it doesn’t take long for the casual listener to notice the disparities; the musical backing is a little too clean, the backing singers too efficient, the tenor sax soloist too smooth, and, above all, Rod, a little too desperate to impress with his whoops, trying his damnedest to convince us that he’s still the same old pub-rocking Rod Stewart despite his full knowledge that the goalposts have been moved. The problem is actually quite simple; he is obviously trying to find his feet in a new environment, and although the musicians are evidently more than keen to help him along with this material, he and they are not quite speaking the same language, and so there is a problem with aesthetic incompatibility.

The problem continues to manifest itself in “Alright For An Hour,” another would-be lad’s rave-up which guitarist and co-writer Jesse Ed Davis seems more determined to turn into pop reggae (although Davis’ unfailingly inventive guitar playing is a real benefit here, as is the bass playing, whoever is playing it). With “All In The Name Of Rock ‘N’ Roll,” Stewart makes his first lunge towards an all-out rocker, complete with police siren and horn section, but despite many inventive touches – for example, a drum intro which squarely predicates the Undertones’ “Teenage Kicks” followed by a minimalist John Cale top register one-note piano riff – he doesn’t quite pull it off, and here another problem becomes extremely noticeable; Stewart’s voice is too far back in the mix. He doesn’t impose himself upon a song like he used to be able to do. Hence, although the band works up a reasonable head of steam, and the central guitar riff is good and compelling, the track simply drags on for too long and has no choice but to come to a fairly abrupt halt, like a train having run out of fuel. Nor does Stewart’s cover of “Drift Away” help solve matters (this is not exactly a “fast” track); Dobie Gray’s original was almost by definition a record of the Watergate period, a reflection by a survivor on what had brought him to this state of resigned acceptance in the first place. Fatally, Stewart substitutes the “free” in the chorus of “Give me the beat, boys, to free my soul” for a second “soothe” and it just doesn’t carry emotional weight; the same can be said of Steve Cropper’s pointillistic and frankly over-fussy guitar lines – again, he seems to want to turn the track into reggae, and the overmiked wah-wahs on the choruses are uncalled for.

The side’s closer, “Stone Cold Sober,” a Stewart/Cropper collaboration, is also, however, the side’s saviour; if the “Fast Side” is a chronicle of two supposedly incompatible musical camps struggling to learn each other’s language, then “Stone Cold Sober” is the result of their finding a common ground. At last, voice and band seem to breathe in and out of each other, rather than being flashily superimposed; for the only time on this side, we get a picture of musicians pounding away in a studio. Furthermore, it is the latest entry in the “Out-Stone The Stones” contest – Ronnie Wood in particular must have heard this and growled his fury – and by some distance the record’s best rocker. Here everything – rhythm, horns, voices – blends together with a great naturalism, and it is from this point that the likes of Primal Scream derived their inspiration. The track fully merits the enthusiastic studio applause which ends it. Rapprochement has been reached.

Then, on the “Slow Side,” Stewart is given the pace and air for his interpretive voice to breathe and flourish – something which certainly wasn’t the case with the ballads on Smiler. His famous cover of Danny Whitton’s “I Don’t Want To Talk About It” brought out a sensitivity and compassion in his performance which had for some time been absent from his work. The 1971 Crazy Horse original falls apart while it is in the process of being performed; if I had not known better, I would have taken it for one of those Lou Barlow lo-fi Sebadoh tryouts on the early Dinosaur Jr albums. But here, Stewart is not rushed by the guitars or bass, or by Arif Mardin’s strings; they all appear to be in conversation with him, or at any rate listening to him. And Mardin’s final key change and huge question mark of an ending are touches of genius.

“It’s Not The Spotlight,” co-written by Gerry Goffin, is also a fine track, helped greatly by David Lindley’s excellent mandolin playing and some awe-inspiring bass work; my guess is Lee Sklar, but my apologies go to Donald “Duck” Dunn, Bob Glaud and David Hood, the other bassists listed in the credits, if one of them was responsible. More important than any of that, however, is Stewart’s magisterially reflective performance; this is an exhausted but happy love song for adults, performed by and for people who have lived through the unimaginable, and opened up an area hitherto largely ignored by rock; what happens when the rockers start to age?

Stewart’s slowed-down Al Green-style reading of the old Isley Brothers hit “This Old Heart Of Mine” – recorded in Hi studios with Green’s musicians, including the unmistakable (and, sadly, soon to be late) Al Jackson on drums – is also a nicely inventive touch, and well executed, the singer coaxing the song’s subtext of insatiable craving out into the open. But the key track here is “Still Love You,” the only song on this side bearing Stewart’s input as a composer. It comes across as a sort of “Maggie May: The Morning After” and has many recognisable elements, including the mandolin, celeste, organ and solo violin. But the “drugstore” reference places the song firmly in Stewart’s new home, and the music isn’t quite the same as it was in 1971 or 1972 (the despairing “Here I am again, writing this letter” is a direct reference to “You Wear It Well”) – once more it is a case of unfamiliar musicians slowly learning and assimilating the singer’s language, and once you get past that barrier, the performance, by singer and band alike, is deeply convincing. The drumming in particular is intelligently placed – if not Olsson or Jackson, it could have been Willie Correa, or Roger Hawkins – and in crucial sections, e.g. the “Two hearts gently pounding as that morning train…” sequence, the whole band appear to pause for breath and crouch down beside Stewart. Thus he is able to sing the “All I’m trying to say in this awful way” refrain with truthfulness, and the “I….I still love you” payoff, though probably rhetorical, and marred by inapt voice-echo, is suitably chilling. I also admire Stewart’s ingenuity as he signs off with a direct Isley Brothers paraphrase: “Guess I’ll always love you…”

All that remains is the venerated “Sailing.” The Sutherland Brothers Band’s 1972 original was not unknown to American audiences – here it flopped, though was included on K-Tel’s 22 Dynamic Hits Volume 2 - and perhaps as a result Stewart’s version didn’t do particularly well in the States as a single (although one has to correct the underselling of Atlantic Crossing’s success in the 2009 sleevenote; the album still made #9 on the Billboard chart and was certified gold). Elsewhere, however, and particularly in Britain, the single of “Sailing” went through the roof and was instrumental in introducing Stewart to a larger audience who wouldn’t necessarily have bothered with, or even heard of, Never A Dull Moment or Ooh La La - and it was certainly crucial in making Atlantic Crossing, for which the song stood as both finale and symbol, the staggering success it was here; reissues included, it stayed on our charts for a total of eighty-nine weeks.

How does Stewart’s “Sailing” stand up, however? Lena ventured the opinion that the song was a sort of compromise between Randy Newman’s “Sail Away” and Steam’s “Na Na Hey Hey Kiss Him Goodbye.” Myself, I note the involvement of Steve Cropper and the general theme of water and would label it the obverse of “Dock Of The Bay” – this is no aimless roam; Stewart sounds vulnerable at times but knows exactly where he is going and how to get there. He sounds regretful – as only he could – because he knows he’s leaving an entire life, a whole history, behind him. But, as with so many “classic” rock singles, “Sailing” makes far more sense in its original context; Mardin’s strings swell up as Stewart pulls away into the sunset, towards the darkness – the singer is saying his true farewell to “us” so long as he can remember who “we” are supposed to be. So the blank, dark space represents the unknown, and Atlantic Crossing, though fitful in finding its goals, deserves more than the history which it possibly gave to itself, as ready-made as the modest pun latent in its title.