(#119: 20 January 1973, 1 week)

Track listing: Intro/I Hope You’ll Stay/In My Hole/Clair/That’s Love/Can I Go With You/But I’m Not/Outro/I’m In Love With You/Who Was It/What Could Be Nicer (Mum The Kettle’s Boiling)/Out Of The Question/The Golden Rule/I’m Leaving/Outro

Despite the Beatles and some of Dylan, the question in early 1973 was still one of “authenticity,” the assumption of one-to-one communication between singer/songwriter and listener in the sense that he or she, the singer/songwriter, was telling you, the listener, directly about their own life. Anything that didn’t fit neatly into the back denim pocket of this personalised talisman was viewed with suspicion, confusion and/or mockery; woe betide further the music which sought to pop balloon notions of what “pop” could, rather than should, be about. Even with the example of Randy Newman, and the nascent ones of Springsteen and Waits, in the USA, no one quite seemed prepared for the return of the character study to pop, of the writer whose business or pleasure it was to tell stories of specific characters which might or might not stand for the writer, or for their nation, or for humanity, or for nothing much.

In particular, no one except the millions who bought his records and ensured the inclusion of this one in our tale knew what to do with Gilbert O’Sullivan. A singer-songwriter managed and encouraged by the manager who had previously renamed and brought us Tom Jones and Engelbert Humperdinck; moreover, one whose early appearance was one of school cap, blazer and shorts, part William Brown, part Keaton, part Chaplin. Even in 1969 it was safe to say that there was nobody else on the scene quite like O’Sullivan, and he remains one of the most singular and inscrutable characters we are likely to meet in this story.

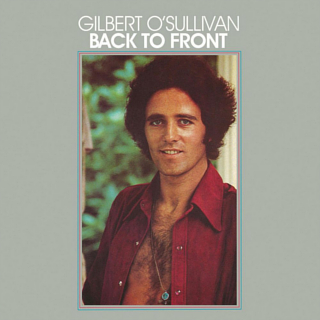

Whatever way you look at it, he doesn’t fit in; by the time of the cover shot, he had amended his appearance to youngish American collegiate, but the medallion, chest hair and vermillion shirt don’t quite gel, and on the reverse he appears concerned, protective of his piano and candelabras, slightly anxious, maybe chuckling on the inside. Within the sleeve came a monochrome poster; there remain the chest hair and medallion, but he looks glumly apprehensive, on the point of blank non-acceptance. He had just scored a US number one with “Alone Again (Naturally)” and naturally everybody asked him whether he really felt suicidal or had lost his parents so tragically (he didn’t and he hadn’t). He sighed decently, wishing they had seen more Alan Bennett or read more Stan Barstow (or, more markedly, Flann O’Brien) or just understood that an author of character studies isn’t necessarily, or at all, their character.

As far as Back To Front is concerned, this is probably just as well since we appear to be presented with a dozen or so different angles towards the same person. I don’t believe that any of it is O’Sullivan, although none of it could have been imagined without him. As the title suggests, the record is already askew; the cheery Phoenix Nights organ intro refers to “those of you leaving” and the final track is entitled “I’m Leaving.” In between these, together with regular proto-Victoria Wood updates on the album’s status (“I’m not quite finished yet,” he reassures us at the end of side one), we are faced with a story which may well be told in reverse (see also Rihanna’s Good Girl Gone Bad) or simply forty or so minutes of daft but wary amiability (there certainly isn’t the head-in-the-‘fridge threat which permeates, say, Wyngarde’s When Sex Leers Its Inquisitive Head).

And the songs go where no other songs of their age were really going. “I Hope You’ll Stay” begins innocently enough as a perky song of childishly courtly love with its references to cups of tea and playing Monopoly, ambling along wearing McCartney’s music-hall hat. ‘Cellos, trumpets and sighing bass guitar arrive in the second verse, but then, without warning, O’Sullivan does a seamless key-changing turnaround into an anti-unemployment rant (“A million out of work is really so good for nothin’/When you think there should be jobs by the dozen”) before slipping back into the song’s original worn cuteness, complete with whistling. “And not to think what the others think”; where does he want us to go?

Were this assessment down to the music alone, Back To Front wouldn’t require much space; the music is almost uniformly standard early seventies Radio 2-friendly MoR-pop, epitomised by Johnnie Spence’s girl/sportscar orchestrations, ruffled shirt percussion and italicised backing vocals. But this is the backing to “In My Hole” wherein O’Sullivan appears to be singing from the perspective of a worm, playing with the dirt, contentedly hiding away from birdsong and bell rings, asking us whether this way of life really is wrong. Despite the evident Milligan influence – a purple daisy named Maisy – on listening we were unexpectedly reminded of Eminem, and in particular the suicidal self-hermit Eminem we hear on “Going Through Changes,” locking himself in, watching the same DVD over and over, Ozzy howling at him as though mocking the bigger life he has exited. No doubt or peril for O’Sullivan in his hole, though; “Hollywood style!” he exclaims at song’s end.

“Clair” was the album’s big single and if its subject matter – a baby sitter’s exasperated but entirely innocent love for his charge – wouldn’t pass the Customs gate today, that may say more about our time than its. It is hard not to marvel at O’Sullivan’s trademark sod-it scansion-defying continuation of sentences into the next line (“I’m going to marry you. Will/You marry me, Uncle Ray?”) or sigh ruefully at now-unpassable couplets such as “I don’t care what people say/To me you’re more than a child.” The overall impression, however, is still one of innocence; of course he’s knackered, but why is he doing it in the first place if not out of love? The premature spectre of that other melancholy Irish-blooded humourist Morrissey, as with the album as a whole, is not far away.

But the remainder of side one steadily becomes less than innocent. “That’s Love” wobbles tentatively on just the right side of the cheesy tightrope with its Sound Gallery/Co-Op discount stamp lushness, and the way its emotions progress is very nourishing, from the scepticism of “I might appear somewhat rude” to the quiet liberated joy of “Knowing inside it must be real”; love wrongfoots him, and he’s happy to be proved wrong (note the completely unexpected Brian Wilson swoon rising up from “you dooooo” and back down into “it’s true” in each middle eight). “Can I Go With You” – where else but in early seventies Britain could there have been a song with such a title? – rumbles politely, like Tony Joe White in Surbiton with brisk harpsichord, until the pace tightens up (“Can I-I-I-I-I-I-I-I?,” chunky Fender Rhodes and guitar), even though his “promise to be true”s flick right back to early Beatles; he’s tried being cynical, but it’s put her off, and now he wants to prove he can be “true,” starting with to himself.

This is followed, however, by the unsettling “But I’m Not.” Rolling along on an Alan Price-style pub piano ostinato (and perhaps refer to Price’s score for O Lucky Man as a sort of sound mirror to this record) with a C&W guitar solo and Jerry Lee Lewis piano references towards the end, O’Sullivan justifies his love by emphasising to her how much he’s done for her, while at the same time warning her against “holding hands with other boys” or being “unkind” with a less than homely sheen. “They think I’m cruel/But I’m not.” His declensions of “no, no, no, no” veer on the grotesque; the song never quite ends, never finds it in itself to end, and things are revealed as less than comfortable as O’Sullivan speeds us hastily out of the first side.

“I’m In Love With You” finds O’Sullivan taking an unexpected but welcome detour into blues-rock lite and the words are fairly straightforward, the singer’s triple rhetorics crouching down, whispering and settling in his bed. Some fine wriggling solo guitar is provided by, I think, Big Jim Sullivan (personnel details are not given on the sleeve and I have been unable to establish the definitive line-up elsewhere). Halfway through, however, O’Sullivan interrupts the song to deliver the following: “Oh, life can be short/Of that there's no doubt/However, I'm not pushed for time/If you can't come out till/Round about nine” – a direct inject of overgrown boy into the adult undergrowth, and we all crease up and adore the man all the more.

The protagonist of “Who Was It,” in contrast, is almost impossible to adore. A pop song as BS Johnson might have imagined (and certainly lyricised) it, here we find O’Sullivan tripping up his Other in order that they might meet, trying to kiss her and managing “to succeed/(In getting it with your fist down below),” and undertaking other unfathomable actions, juxtaposing them with archaisms (“unabashed”) and music hall nostalgia (“A bloomin’ shame,” voiced in a chorus of descending triplets), and all because he loves her. It’s actively disturbing, and if I think of “I Want You” by that yet other melancholy Irish-blooded humourist Elvis Costello, the lineage is clear; like Costello, O’Sullivan is experimenting with what he can actually get away with in the context of a standard pop song, at least in terms of subject matter.

“What Could Be Nicer” is an exemplary character study which demonstrates O’Sullivan’s ability to look at the same picture from within the heads of different observers. It’s a family gathering, perhaps on a Sunday, or simply a picture of an extended family whose younger members can’t yet quite afford to find their own place. Home Service strings and choir provide the cushions, but the observations are extremely knowing; the older members of the family pass the time with routine questions about Helen’s letter to Uncle Tony, there is the wonder of two youngsters ready to venture out into the world balanced by the huge regret (complete with the intimations of minor key dread provided by the choir in the middle eight) that these same people will end up becoming old and getting ejected into the cold, left out of society. Look at that crying baby, listen to that kettle – is that all there is, and does it mean so much more than it sounds, is this heaven or hell? O’Sullivan’s camera eye roves among the heads and souls, pans out again to repeat the original picture; this is a fine balance to the exquisite balance struck between shock at personal rejection and the slowly mounting pains of bereavement in “Naturally,” and it is perhaps the album’s most moving song.

“Out Of The Question,” a single in some territories (though not in Britain), is a racy will you/won’t you precursor to Katy Perry’s “Hot And Cold,” though its protagonist’s ambitions are smaller than he might care to claim (“[We could have] Sailed empty handed round the world”) and he never misses a moment to emphasise that she, not he, is the one to blame (“I’m sorry, of course, but the fault is hers”). Whereas “The Golden Rule” is near-impenetrable; a Randy Newman canter with Robert Wyatt-esque melodic twists and turns over which O’Sullivan muses over the theme which has carried him through the record – in summary, you might take me for a fool, but I am most certainly not one – taking in Niagara Falls, getting the belt for a bad report card, liking the sound of pneumatic drills (“Don’t be such a miser!/At the most, a fiver’s all you pay”) and meditating on parental wham-bam (“And as you can see/The result was me”) before venturing out with an incomprehensible (and again Milligan-inspired, if not Joyce-inspired, if indeed not Coronation Street-inspired; in O'Sullivan's lyrics there is the frequent reminder of washing-line conversations, long and winding perorations about nothing in particular, beginning at A and ending up in J having gone through R) stream-of-consciousness spiel about money growing on trees, oranges and lemons, “not forgetting melons.”

Finally, O’Sullivan takes things out – or possibly leads them back in – with the space age Moog/fuzz guitar-powered rocker “I’m Leaving.” He’s had it with “this place,” can’t wait to shake it off and leave it behind, its empty streets filled with gutters. I have no idea whether he’s singing about Swindon, whence the O’Sullivan family decamped from Waterford early on in his life and where he was effectively brought up; still, it is possible to think of this as the record’s opening principled declaration before working backwards through several states and ages of love and life. His “Just ‘cuz I won’t spend my money here” – especially the “money here” – is essentially a punk sneer and leads into a high-pitched guitar solo. As the track slowly rocks out of the picture, O’Sullivan whoops like a Freddy Cannon reimagined by a younger Roddy Doyle...and then that silent movie piano and “I’m almost finished now, I’m almost finished now”...

The intro/outro concept was not new – O’Sullivan had used it on his debut album Himself - but I cannot think of any other album within Then Play Long that treats the fourth wall in quite the same way; he’s playing with us, dodging behind a wall or a bush if we get too close, and yet he is as completely in control of his environment as the worm – or mole – in “In My Hole,” regardless of width or length. He knows exactly what he is doing every step of the way, and in the intervening four decades has continued to do likewise; an admirable, stoical refusal to bend to any passing trend or vogue, a need to remain as true as possible to what he wants to say and express as profound, if not as palpably intense, as that of Van Morrison or even Scott Walker. It is a pity that Back To Front is currently only available on CD as an expensive and hard-to-find Japanese import – O’Sullivan has never stopped being a superstar in Japan – but its creator is noticeably reticent about unleashing his back catalogue in the UK (the excellent Berry Vest Of... compilation from 2003 is already out of print and reaching extraordinary second-hand prices); perhaps he feels that there isn’t the market, or simply wants his audience to keep up with where he is going now. His current album is entitled Gilbertville and the cover finds him hitch-hiking, his grand piano propped up beside him like a rucksack. Wherever and whenever you want him, he’ll turn up and start making his own sense. After all, he is in the business and the art of telling stories.