(#405: 31 March 1990, 1 week)

Track listing: Space

Oddity/Starman/John, I’m Only Dancing/Changes/Ziggy Stardust/Suffragette City/The

Jean Genie/Life On Mars?/Diamond Dogs/Rebel Rebel/Young Americans/Fame ‘90/Golden

Years/Sound And Vision/“Heroes”/Ashes To Ashes/Fashion/Let’s Dance/China

Girl/Blue Jean

(Author’s Note: In the fine tradition of the early Now series, you actually get less value if you buy the CD edition; “Starman,”

“Life On Mars?” and “Sound And Vision” appear only on the LP and cassette

editions, and their omission from the CD strikes me as being as ridiculous a

move as releasing a Beatles compilation which left out “Please Please Me,” “Strawberry

Fields Forever” and “I Am The Walrus.” Who on earth would buy that?)

The delay is because Lena was originally going to write this

entry but found dealing with the masses of information available on Bowie stressful to the

point where even the chance hearing of one of his songs induced a headache. So

she has passed it on to me, and I have to say that listening to ChangesBowie is one of the strongest

arguments in favour of paracetamol you’re ever likely to encounter.

As much as some of the number one albums of the nineties

argue strongly in favour of a future, there was an equal and opposite reaction

which heavily promoted the virtues of looking back. For the second time in TPL’s history, a generation was

compelled, or persuaded, to re-examine its own memories, and so there are

plenty of long-term hits compilations coming up, of which this is the first; a

highly selective summary which includes nothing recorded before 1969 or after

1984.

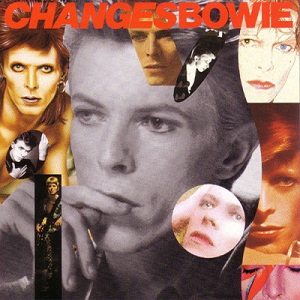

The cover alone indicates that Bowie was as appalling a

custodian of his own work as Apple were of the Beatles, featuring a photograph

identical to that on the cover of 1976’s ChangesOneBowie

but pasted over haphazardly with snippets of other Bowie album covers like a

neglected advertising hoarding. Indeed, as far as the CD edition is concerned,

its first eleven songs are identical to those on ChangesOneBowie, except that the latter included the original and

immeasurably superior version of “Fame.” From 1981’s ChangesTwoBowie, only “Starman” and “Sound And Vision” reappear,

although the “Ashes To Ashes” and “Fashion” on ChangesBowie

are the full album versions, not the single mixes.

The compilation throws up the extremely important question

of whether I have the energy to say anything new about these songs, which on

the CD in particular seem sequenced in a way to make Bowie come across as bland and Radio

2-friendly as possible. This is the “classic” Bowie, the only one most people,

if they are honest with themselves, give a damn about. It is the Ziggy crutch

which leads to situations where Chris O’Leary’s Rebel Rebel, without a doubt the best, most informed and most

trenchant book about Bowie that you will ever read, is not reviewed in

broadsheets or magazines, cannot be found in bookshops, whereas cut-and-paste

books of photographs or “In His Own Words” rush jobs are present in their

abundance. Indeed it would not be hyperbolic to state that Rebel Rebel is vastly superior in intent and delivery to Revolution In The Head – the latter

gives rise to a serious consideration of the worth of “good writing” since the

twenty-one years since its first publication have demonstrated its author to

have been wrong-headed about nearly everything that the Beatles did (and its

preface and postscript now seem, more than ever, like extended cries for help);

however, because it was well-written, it has acquired the status of a Bible.

Nevertheless, ChangesBowie

simply leaves me exhausted. It paints a picture of a chancer who had a hit in

the late sixties about drug addiction which everybody assumed was a moon

landing cash-in and then progressed to boring, sub-Stones cock rock schlock

before getting depressed but good in the second half of the seventies and the

very beginning of the eighties, and emerging out the other side with boring,

sub-Asia adult orientated rock schlock. Even the Aladdin Sane and Diamond Dogs

singles sound shockingly anaemic out of their albums’ context, suggesting that

some remixing had been done.

“Young Americans” is so good because it marks the moment

when Bowie

wakes up with a start from his romantic fifties greasy dreams and wonders aloud

what all this bullshit has been hiding. “Golden Years” in conception, delivery,

performance and production is about as perfect as pop songs get, even

withstanding a Crackerjack assault. “’Heroes’”

is meaningless in its single edit other than setting the stage for big eighties

rock with its Big, Meaningful Statements; Live Aid proved how easily this pop

Frippertronics could turn into standard stadium fare, but Bowie, Eno and Fripp

all approach the full album version

with a mortified exuberance which suggests that this might be the last song

anybody sings (like its nephew, “Being Boring,” it did only modest commercial

business but eventually evolved into one of his big crowd-pleasers on stage).

But the deathly hallow of the last three songs, from Bowie’s cleaned-up, corporate, forget-the-weird-stuff-please eighties, suggests that nothing was learned and most things that mattered were forgotten. Bowie is mainly interesting when whatever mask he is wearing at any given time falls. As a Rich Rock Tapestrian in the line of Rod, Elton and Sting, he might as well be a Hallmark Collectible Ornaments advertisement. The nadir of this album is the "Gass mix" (somebody called John Gass, under Bowie's supervision) of "Fame" which systematically strips out most of what was interesting, attractive and wrongfooting about the original, including most of the Lennon input. Did Bowie really feel a burning need to remind those Jesus Jones who was scratch n' mix boss?

Next: Some heavenly pop hits, if anybody wants them.

But the deathly hallow of the last three songs, from Bowie’s cleaned-up, corporate, forget-the-weird-stuff-please eighties, suggests that nothing was learned and most things that mattered were forgotten. Bowie is mainly interesting when whatever mask he is wearing at any given time falls. As a Rich Rock Tapestrian in the line of Rod, Elton and Sting, he might as well be a Hallmark Collectible Ornaments advertisement. The nadir of this album is the "Gass mix" (somebody called John Gass, under Bowie's supervision) of "Fame" which systematically strips out most of what was interesting, attractive and wrongfooting about the original, including most of the Lennon input. Did Bowie really feel a burning need to remind those Jesus Jones who was scratch n' mix boss?

Next: Some heavenly pop hits, if anybody wants them.