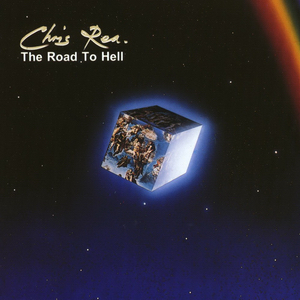

(#401: 11 November

1989, 3 weeks)

Track listing: The

Road To Hell (Part I)/The Road To Hell (Part II)/You Must Be Evil/Texas/Looking

For A Rainbow/Your Warm And Tender Love/Daytona/That’s What They Always Say/I

Just Wanna Be With You/Tell Me There’s A Heaven

PROLOGUE I

On 26 May 1989, Don Revie died in Murrayfield Hospital,

Edinburgh. He was sixty-one years old and had for some time been suffering from

motor neurone disease. After leaving Leeds United to manage the England team

fifteen years previously, he never recaptured his former success, either with

England or the UAE and other Arabic teams which he later managed. Gigantic

question marks, mainly centred on financial matters and fair play, ensured that

he became a figure conveniently forgotten about by the football establishment, left

in the corner, out of sight, purposely neglected.

PROLOGUE II

In 1989, Brian Clough’s Nottingham Forest finished third

in the League and won both the League Cup and the Full Members Cup. They also

reached the semi-final of that year’s FA Cup. Their opponents were Liverpool.

But they lost to Liverpool in the replay. A replay was necessary because the

original match had to be abandoned after six minutes of play.

The original FA Cup semi-final, which was to

be played at the Hillsborough stadium.

“She says that mess

it don’t get no better

There’s gonna come

a day

Someone gonna get

killed out there”

ENVOI I

Clough and Revie grew up about a mile apart from each

other in Middlesbrough; Clough in Valley Road, Revie in Bell Street. In between

used to be the old Middlesbrough ground, Ayresome Park, and there still exists

Albert Park. As managers, Clough and Revie had little time for each other, as

became painfully apparent when Clough surprisingly but only briefly replaced

Revie as manager of Leeds United. Revie was keen and quick to get away, in the

first instance to Leicester City as a player, but Clough never neglected his

roots.

What is certain is that both Clough and Revie would have

frequently spent time in the now-defunct establishment which was just across

the road from Albert Park; indeed it was where Clough met his wife Barbara, and

where he would frequently retreat for discussions with his sidekick Peter

Taylor.

This establishment was Rea’s Ice Cream parlour.

“A promise to get

out

That’s what it’s

all about”

BACKGROUND I

Camillo Rea‘s father was from New York but somehow ended

up in Middlesbrough. He started an ice cream business – essentially a factory

and a cafe, later to be followed by numerous other cafes through north-east

England – but Camillo and his brother Gaetano took over and expanded

the family business in 1946. Camillo had seven children, all of whom were expected to

follow him into the business. The young Chris recalls having to work in his

father’s coffee bar, serving behind the counter and washing the dishes.

Gradually becoming disillusioned with this way of living,

Chris eventually opted to pursue a career in music. A rift developed between him

and his father, and although Camillo Rea lived on until almost the end of 2010,

there appears never to have been a reconciliation.

“Tell me that they’re

happy now

Papa tell me that

it’s so”

THE CLASH

It was their last single. It came out in late September

1985, the same week as “Slave To The Rhythm,” “Alive And Kicking” and others.

It was the only single from the Clash album that radio and Sony would much

rather have you forget or not know that it ever existed. I haven’t spoken much here

about The Clash because they never had a number one album, although both Give ‘Em Enough Rope and Combat Rock – their most “American”

records – came very close, and maybe also because they didn’t quite avoid

becoming the critically acclaimed albums act that they, or at least most of

them, had not wanted to become in the first place. At least, not when Mick

Jones was there.

But by 1985 Jones was two years gone, and there were just

Strummer, Simonon, Rhodes and three new recruits, trying to work their way back

to why they had ever wanted to do this, as if they had known more about what

The Clash should have meant than the man who had originally formed the group

and recruited them.

You hardly ever hear, or hear about, “This Is England,”

but it is The Clash and Joe Strummer’s greatest and most forsaken moment.

Always best when lost, alone and confused – “Complete Control” starts out as a

diatribe against their record company but ends up questioning art and motive, “White

Man In Hammersmith Palais” demonstrates how someone can live and grow up

somewhere and not realise until too late that they know nothing about their own

home, “Death Is A Star” being the romantic response to “Decades” – the song begins

with a midtempo dub rhythm, slowly joined by a loop of children’s voices and a

cloud of synthesiser.

And then Strummer angrily barges in with his voice, as

exhausted as Lennon’s at the end of “Twist And Shout,” and grim guitar, and sings

about what might be a riot, or an extermination process (“Are they howling out or doing somebody

harm?”), during which a woman grabs him coldly by the arm and declares “THIS IS

ENGLAND.” The chorus follows, with the title echoed by a huge football crowd.

This is the 1985 England of Bradford, Broadwater Farm and Heysel. Strummer then

muses about the wretched lot of the Falklands soldier, or just the ordinary

worker (“He won’t go for the carrot/They beat him by the pole”).

The steady decline continues. “I got my motorcycle jacket

but I’m walking all the time”

“I’m going to Texas

I’m going to Texas

Watch me walking

Watch me walking”

both anticipates and outdoes “Motorcycle Emptiness”; the

aimless and pointlessness of “rebellion” with punk having resulted in little

more than the Falklands (“Ice from a

dying creed”).

Then the mood gets violent again; there are race riots –

they have ended up where they started, but is all that people thought a “White

Riot” meant? – and then the British beat themselves over the head with their

own batons, shrug their shoulders and say well that’s the way it is, THIS IS

ENGLAND, the “land of illegal dances” half a decade ahead of rave (perhaps just

another, more placid baton). “The newspapers being read/Who dares to protest?”

Strummer asks rhetorically. Then everything falls, dies away except that blunt

guitar, grinding out its punk riff – DO ANY OF YOU DOUGHNUTS REMEMBER WHAT THIS

WAS SUPPOSED TO MEAN ONCE? – seemingly forever, alone on the planet. The music

discreetly fades until the guitar exhausts itself, stops and gives a feedback

weep, for its country and this fruitless culture.

HELL

Cut The Crap is

a mess, but the exhilarating mess punk had once promised to be; the opening “Dictator”

with its arsenal of beatboxes and Video City samples, suggests the band Big

Audio Dynamite might have been (the words here which ring out of the page are: “You

know once there was freedom/You know how dangerous that can be”) and it is no

surprise that in the following year both approaches fused and BAD put out the

sometimes fantastic No 10 Upping Street

– essentially a Clash-in-exile album (“Sightsee MC” still sounds like the last

song you’d ever hear in London).

This record, however

– it’s only the penultimate number one of the eighties, but we can close down

the decade with it – begins with a different use of found sounds; there is an

ominous drone in the middleground. In the distance we hear a ghostly piano,

picking out a nursery song

the five-year-old

piano student at home, at his piano, with his Ministeps To Music tutorial books, and a black-and-white

television on the other side of the same room, the blue light, the theme songs,

the fear

while closer up there are scattered voices from radio

scans, coming from all across the world, as though this were the fatal and

total pile-up and all that was left of the world, a vague reminder of what

humanity once aspired to. But there also enter deep Cooder curves of

Middlesbrough delta guitar and that drone won’t go away.

It is the M25 motorway which orbits, but does not enter,

London at a twenty-five-mile radius. Travelling into the city by train from any

direction, its appearance is a welcome signifier, indicating that the traveller

is almost home.

But the thing is that Britain will never learn, has

always been parsimonious about so many things that it becomes destructive. In

fifties America they had giant refrigerators, comic books and rock ‘n’ roll; in

Britain we continued to allow ourselves to be punished with ration books and

Hoggart lectures. It is as if Britain, which is fatally an island, has always

felt unworthy of itself, thinks that it does not deserve what it receives, and

yet fiercely protects the interests of those who have received far, far more

than they deserve.

Britain was never America. America has long, unbroken

highways; motorways here are higgledy-piggledy things, forever winding around

and narrowing themselves to protect the interests of landowners whose

privileges date back to the time of agrarian enclosures. Britain is in the

north of Europe and is therefore cold and damp most of the time.

Most importantly, Britain cannot, or will not, plan

ahead. The reason why getting around London by road is such an arduous task is

because road-widening was rejected by vested interests in the nineteenth century

who preferred roads which had been built to accommodate horse-drawn Victorian

carriages. And I do not suppose that anybody involved in planning the M25,

which by 1989 had been in operation for around three years – indeed was opened

by the Prime Minister herself – had the remotest notion that its highways would

rapidly be filled up by motorists keen on avoiding London. All motorists who probably

also harboured the dream of getting away, of cruising down long, unbroken

highways, but invariably think it’s always the other motorists’ fault.

But the narrator here has not quite broken down; instead,

he is sitting still, in gridlock. He sees a woman in the distance. She slowly

comes up to his car, and when she bends down to speak to the driver, “A fearful

pressure paralysed me in my shadow.” She asks “Son, what are you doing here?”

He explains – calling her “Mama” with the implication that she is a ghost (“My

fear for you has turned me in my grave”) – that he has “come to the valley of

the rich” to sell himself. But she sadly tells him that in fact he is on the

road to Hell.

If the woman grabbing Strummer by the arm in “This Is

England” is Thatcher – how could she not be? – then this woman’s identity is

more ambiguous. It could theoretically

be a gloating Thatcher, but I note that Rea’s actual mother, Winifred, died in

1983. But the way in which he announces the song and album’s name makes it feel

like the last song anybody would

hear.

Martin Ditcham’s drums kick in, and the song starts up

proper. The trick becomes evident to those who would listen – and Rea makes a

point of making sure that the listener doesn’t

miss hearing what he has to say – namely that, although this music superficially sounds like Dire

Straits/yuppie-pleasing hi-fi/car-friendly AoR, he is using the uniform of the

enemy to turn them back on themselves.

“I’m underneath the

streetlights

But the light of

joy I know

Scared beyond

belief way down in the shadows”

“And at night,

there came another dimension...of terror. As I prowled, I knew how scared I

was, dead scared, yet not too scared to prowl.”

(Ian S Munro)

“And the perverted

fear of violence

Chokes a smile on

every face”

We’re really not too far away here from “This Is England,”

are we? Nor indeed from Heaven 17, with the useless credit jamming up the

roads.

“Look out world,

take a good look

What comes down

here

You must learn this

lesson fast

And learn it well”

If the second part of “The Road To Hell”

predicates anything, it’s Leonard Cohen’s “The Future” from three years later.

Possibly the most depressing thing about the latter song is how painfully

accurate all his predictions have turned out to be – “Give me Christ or give me

Hiroshima” indeed. I don’t know whether Cohen ever heard “The Road To Hell” but

I do know that before going solo, Chris Rea played in a band called The

Beautiful Losers.

“This ain’t no

upwardly mobile freeway

OH NO, THIS IS THE

ROAD TO HELL.”

Upon which guitars, played by both Rea and Robert Ahwai,

scream out jagged, torrid lines which have much more to do with Neil Young than

with Knopfler. Always on this album the guitars sound as though in

insurmountable pain.

BACKGROUND II

Chris Rea did not

actually buy a guitar until he was in his early twenties; a late time to start.

He taught himself to play it. Although influenced by his parents’ opera and

light classical records, as a musician his main influences came from the blues,

notably Sonny Boy Williamso, Charley Patton and Blind Willie Johnson;

contemporary guitarists he admired included Ry Cooder and Joe Walsh. Although

The Beautiful Losers were voted Best Newcomers in the Melody Maker poll of 1975, he had already been signed as

a solo artist to Magnet Records the year before by the label’s head of A&R,

Pete Waterman, but had to wait until 1978 before “Fool (If You Think It’s Over)”

became a Billboard Top 20 hit. In

Britain it missed the charts entirely on its first release and only scraped

into the Top 30 upon reissue; it wasn’t until Elkie Brooks’ 1982 hit cover of

the same song that the UK really began to pay attention to Rea’s music. He

spent much of the eighties steadily building up his profile, particularly on

the Continent, where he was a huge star long before his UK breakthrough. Given,

however, that whenever he hit big he felt obliged to conform to what other

people expected of him, it is no surprise that, following serious illness in the

early 2000s, Rea resolved to revert to the kind of music he wanted to make,

since when he has re-established himself as a highly respected blues performer

who continues to record and tour with great success.

He comes home from work, and his young daughter is crying

over something they’ve shown on the news. He is outraged – “This ain’t even

dinner time!,” “What’s wrong with you?,” “You don’t have to show that stuff/Can’t

you show us some RESPECT?,” and threatening “I wish you were here”s. He

concludes, chillingly, “You must be evil” – a warped and twisted media ready to

make children cry and a nation collapse (“You giving out some bad ideas here”).

“Looking For A Rainbow” grinds on for an agonising eight

minutes and twenty seconds; he and his family have come down to the valley (of

the shadow of death?) to seek their fortune – or so it would seem, because as

the song progresses their real mission becomes clearer, “Maggie’s little children.../looking

for Maggie’s farm” are actually here to exact their revenge...

“You can’t leave us

dying this time

‘Cos we’re all

around your door”

Between 2008-10 it was erroneously stated in

some newspapers that Chris Rea had donated large sums of money to the

Conservative Party and that he had been a long-time Conservative supporter.

What the newspapers had done was to confuse him with another Chris Rea, a Sheffield businessman who is

Group Managing Director of mechanical seal manufacturers AESSEAL and who had

indeed donated money to the Conservatives. Although I note the strong work

ethic that comes from growing up in an Italian family – and I should know – I am

also aware that no one could have made a record like The Road To Hell and be a Conservative. Instead, in the

album sleeve, Rea acknowledges “Everyone in all the governments.” Given that he

values personal freedom and driving in particular, however, it is perhaps best

to view the record as the rueful reflections of a disappointed small-c

conservative, much in the vein of disappointed literary socialists such as

Orwell, Huxley and Koestler.

In “Your Warm And Tender Love,” he succeeds in finding refuge

from the growing storm in love, the light which pierces all darkness. By the

time of “I Just Wanna Be With You,” however, his need is turning into an

obsession. “I just wanna be with you,” he reiterates, over and over, “’til the

final curtain falls” and as an alternative to “know[ing] nothing at all.” “I

know there’s a price to pay for doing what we do,” he cryptically admits, but

that is no deterrence to their doing it.

“That’s What They Always Say” is a sardonic rejoinder to

those who talk all the time about getting away, making the break from the rat

race, but who in their hearts know they’ll stay right where they are, gambling

on that golden bridge just around the corner, “always one more thing to do.”

But finally there is the realisation that there is no escape from this

voluntary self-imprisonment. “The money junkie fades away,” remarks Rea,

perhaps aware that he too will opt to hang on.

But there are those dreams, the dreams of “Texas.” As the

skies of Britain collapse around him and his wife (“Been watching some TV...It’s

all gone crazy”) he fantasises about a place that priorities quarterbacks over

quarterlights – “Warm winds blowing/Heating blue sky/And a road that goes

forever.” Yet he concludes: “Watch me walking.” If he gets there, however, he’ll

drive in his “Daytona,” a tribute to the Ferrari 365 GTB/4 Daytona classic car,

which ceased production in 1973 but of which he still dreams exquisitely (“Twelve

wild horses in silver chains/Calling out to me”). As with the “sweet angel” in “I

Just Wanna Be With You,” he implores the Daytona to “shine your light on me.”

Because nothing could be darker than this.

It is almost the end of the record, this story of the mad

dreams of the man stuck in his car who, for the second time, comes home to find

his daughter – by 1989 Rea had two young daughters; nowhere are you really made

to forget that this record is the work of a parent – watching television. And

now, it is about abuse, and it is about violence and death – and beyond

outrage, the narrator is at a loss what to say.

“Grandpa says they’re happy now” – this is a song which

involves three generations. He knows what grandpa is saying, and why he’s saying

it, but he can’t find it in himself to believe it- Max Middleton’s string

section freezes on the word “ice.”

She is asking him, his little girl, to tell her that

there’s a heaven, that these people will go somewhere, because otherwise why is

she seeing all of this?

He freezes and the strings descend into mild discordance

before again settling. He turns to us for an answer: “So do I tell her that it’s

true? That there’s a place for me and you?” But you can tell – “every painful

crack of bones” – that he can’t tell her this story.

The key line is:

“What makes those

men do what they do?”

...and you could say that this tale, this Then Play Long story, has been heading

towards this conclusion all along, that the fundamental problem is not simply a

question of why men do what they do, but the question of what constitutes evil.

Because the closing vocal section of this song is truly

terrifying, as the timpani rolls and the camera pulls back – “And I’m looking at

the father and the son” as though the end credits are rolling, “And I’m looking

at the mother and the daughter” – and then the strings become atonal again,

with a thudding timpani heartbeat, as he sings “And I’m watching them in tears

of pain/And I’m watching them suffer/DON’T TELL THAT LITTLE GIRL/TELL ME.”

And then he sings the chorus again, but this time he’s

the one asking, desperate to be convinced that it’s true, that some redemption

must exist somewhere. The orchestra plays out as though this were a Lloyd

Webber musical, and after some “Don’t Cry For Me Argentina” oboe flourishes,

the song, and the record, and its decade, are all laid to rest. There is

nothing left save the silence.

The question is not just how a record like this ever got

to number one, but what it means in greater terms.

We closed down the sixties with “You Can’t Always Get

What You Want,” saw out the seventies with “I Was Only Joking,” and now we are

nearly done with the eighties, by way of its epitaph.

But with “Tell Me There’s A Heaven” in particular – one of

this tale’s key songs – there is the sense of a greater and more horrific truth

being revealed, and revelation is perhaps the last thing that needed to be

done, since it all seems to have happened, as the book title goes, in plain

sight. Here we are at the end of a decade whose number one albums have nearly

all been about the problems faced by men and women and/or lovers in

communicating with each other, and it ends, to all intents and purposes, with

the notion that it is the medium itself which is the true evil, a declaration of

intent by somebody – Rea in 1989 was thirty-eight years old – who has lived through

all of Then Play Long and knows the

whole story. The story of pop and rock music only really concerned with

alerting its very young audience to an adult world. An era which may prove to

be, as the Descendants have it,

rotten to the core.

And you realise why Rea might have been so keen to get

his wife and kids over to Texas – as Americans glance at them on their long,

endless highways and retort: “well, why do you think we left Britain in the

first place?” – or anywhere that’s far, far away from evil people like

Thatcher, Savile, Sutcliffe, Gadd, a country rotting because of its very own

and deeply perverted traditions. And yet there is still hope. The half-Scottish

Joe Strummer pointedly called his best song “This Is England.” And

while many might still view the road to Budapest as the road to Hell, maybe

that signifies a major turnaround in how people are prepared to act towards

their fellow humans. Perhaps the corporate media’s bluff has been fatally

called; get away from television, newspapers, the internet, and realise that

you can still make your own decisions about how the world operates. Strip away

the neoliberal gaffa tape and you’ll find ordinary, generous and welcoming

people beneath.

CONCLUSION

As the cover of this album clearly demonstrates, our world doesn't have to be compacted into profitable garbage like a spent car, and even in the darkest of corners, there always lurks a rainbow.

ENVOI II

“Change has a way of just walking up and punching me in the

face” – Veronica Mars