Tuesday, 18 May 2010

George HARRISON: All Things Must Pass

(#88: 6 February 1971, 8 weeks)

Track listing: I’d Have You Anytime/My Sweet Lord/Wah-Wah/Isn’t It A Pity (Version One)/What Is Life/If Not For You/Behind That Locked Door/Let It Down/Run Of The Mill/Beware Of Darkness/Apple Scruffs/Ballad Of Sir Frankie Crisp (Let It Roll)/Awaiting On You All/All Things Must Pass/I Dig Love/Art Of Dying/Isn’t It A Pity (Version Two)/Hear Me Lord/Out Of The Blue/It’s Johnny’s Birthday/Plug Me In/I Remember Jeep/Thanks For The Pepperoni

With the CD revolution came an unwelcome urge on the part of some artists to revisit and “correct” their previous works. The Beatles continue to be guiltier at this than most, as though they were so impassively perfect as to permit themselves further attempts at perfection. Prior to his death, George Harrison had begun to plan a major overhaul of his back catalogue on CD, but only All Things Must Pass received the full treatment in his lifetime. For a decade his revised version has been the only version commercially available, and it is my regrettable duty to state that it is a travesty, not to mention a dreadful indicator of how little artists are sometimes able to grasp the implications of their own work. There are sonic clean-ups, redone guitar and rhythm parts, re-recordings, alternate takes, and perhaps worst of all, a tinted colourisation of the original cover, with further “humorous” updates within the package. While one can hear what everyone is doing far more clearly, the muddiness of the original record’s density – thanks in no small part to producer Phil Spector – was vital to express its quietly turbulent state of mind.

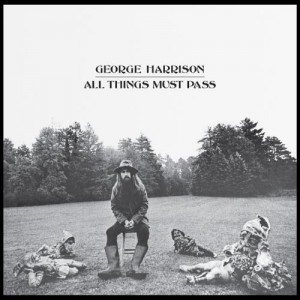

For this purpose, then, I have adhered to the original triple-LP box set, and its downcast presentation remains the perfect visualisation of the confusion that was clearly flowing through Harrison’s mind at the time he recorded these twenty-three songs. The monochromatic strangeness of the cover suited the times; where, indeed, had the times gone, wonders a bemused Harrison, sitting alone in his huge garden, his eyes wildly veering to his left, his only audience four reclining, gently mocking garden gnomes, spread out on the lawn before him. He left the Beatles for this? What, you can see him wondering, am I supposed to do now?

He had reached home, all right, but what sort of home is it that is being represented in the poster which accompanied initial copies of the album (and which indeed is present in my copy)? This was not a cosy, sexy pin-up shot for the Apple Scruffs; we see George, in the front hall of his mansion, facing us, his back to the front door. The sunlight peering through the door is the only light in the picture; there is a mirror on either side of him. He stares impassively, or is that confusedly; his face, almost completely obscured by his beard, and upper torso are visible, but the rest is an unbearable hole of blackness. Below his expression lies a terrible void. The album demonstrates his attempts to shine some light into this unaccounted-for darkness.

Despite the bleakness of the package, the record opens with one of his best songs – although, significantly, he is singing the words of another. Bob Dylan gave him the lyric for “I’d Have You Anytime” in 1968 and two years later he set it to music. It is perhaps the record’s most fulfilled and fully formed song, and maybe even its happiest; a loose, relaxed guitar slides across a lagoon – this could almost be Andy Williams singing Dylan – shimmering in lovely shadows from G major to B flat major to C minor seventh, alternating with a rhetorical waltz sequence. All the while, Harrison sounds content and earthy; his love is clearly a human one, his desire sensually generous, although he could equally be singing to his post-Beatles audience (“I know I’ve been here,” “Let me show you,” “Let me grow upon you”), welcoming them into his new abode. Developing upon the promise of “Something,” he sounds completed, returned to source. Like the opening chord of Vaughan Williams’ Fantasia On A Theme Of Thomas Tallis, it presents a vision of perfection which will never quite be regained.

“My Sweet Lord” was a reluctant single – Harrison initially didn’t want any singles released from the album – and its plea to worship sounds just as reluctant, perhaps even fearful. A soundtrack to the rise of Christian hippiedom, yes, but the portrait of internal confusion is still vivid. I don’t believe Harrison intended to utilise “He’s So Fine” quite so blatantly – his original inspiration, and the song’s real structural reference point, was “Oh Happy Day,” the surprise 1969 gospel crossover hit for the Edwin Hawkins Singers – but note how the song’s opening third is rather fuzzy in its arrangement (much as the singer’s mind is undecided) before clarification and revelation are reached by means of Spector’s delicate fading in of Ringo Starr and Jim Gordon’s double drums halfway through. Now his confidence rises, now the other voices join him to unify Christianity and Hinduism, now the song opens up to welcome in the sunshine. It is remarkable, however, how Harrison treats his God like the girl from round the corner; “I really want to go with you,” as though he wants God as his girlfriend, to take Him out dancing. Yet, underlying all of this, is a perhaps terrifying uncertainty: “But it takes so LONG, my Lord!” he cries at steadily more intense intervals. And the song never really resolves, but carries onto its extended singalong fadeout.

With “Wah-Wah,” written after Harrison fled the studios after yet another fracas with McCartney during the Let It Be sessions, something like regretful rage makes itself known. As a track it is overwhelmingly powerful, Clapton’s agitated lead guitar darting around its cornices like a trapped seagull, with brass seemingly glued on with Sellotape; Spector keeps it very trebly – I think of both the Stones’ “We Love You” and the Associates’ “Kitchen Person” - but the overall spread is nearly titanic. Its regular barbershop harmony breakouts almost drown the song entirely but in terms of range and intent “Wah-Wah” clearly signposts nineties Britpop – the Oasis shrug of the hurt shoulder, the Supergrass damn-you-ness (see the latter’s 1996 single “Going Out” for a direct descendent, to put it diplomatically); it’s all there, and the Clapton/Harrison duel which climaxes the song indicates that the cheaper than a dime tears are still moist and felt.

“Isn’t It A Pity” appears in the first of two versions; the police siren piano seems a nod to “I Am A Walrus” and the song’s harmonies rotate gloomily up and down the G major scale. Here Harrison makes his bravest of farewells to the Beatle age – remember that nearly all of these songs were composed in the sixties with the Beatles in mind, and that some even made it to demo status before visiting the “junior partner” recycle bin – hanging on the word “hearts” for the dearest of lives. Serene strings enter the picture and Ringo’s trademark rolls, backed by sympathetically tinkling piano and supported by Harrison’s downtrodden slide guitar, move the song into a would-be “Hey Jude” cyclical chant, but this seems a “Hey Jude” from which people are absent; the echoing shouts at the back of the picture which enter in the fadeout’s later stages appear to come from nothing save ghosts.

Harrison perks up somewhat for side two; “What Is Life” is a dynamic piece of bubblegum optimism, clearly indebted to Motown with its foursquare Four Tops beat, although the distantly mixed horns and Spectorian castanets (as well as the punctumising tambourine which enlivens the song from its second chorus onwards) cast other shades across its cautious joyfulness. The “Penny Lane” trumpet peals and pearls of drifting guitar harmonics suggest a cross between Stevie Wonder’s “Uptight” and the Byrds’ “Lady Friend” playing on separate jukeboxes in opposing corners of the same room. “What is my life without your love?” he asks, not entirely rhetorically – but who is this “you”? It doesn’t sound like the same, earthly one of “I’d Have You Anytime.” Likewise, his take on Dylan’s “If Not For You” is certainly much less troubled than the composer’s own reading on New Morning, in a lower key and principally powered by Gary Wright’s thoughtful piano – but the “You” appears to demand its capital “Y.”

“Behind That Locked Door” ventures further into post-John Wesley Harding country-rock, a stately ballad waltz with some fine work from Pete Drake’s pedal steel and Billy Preston’s organ, but it’s clear from the song’s shift from vaguely accusatory third person into painful first person that it’s Harrison’s own heart that is locked away from view, marooned behind that metaphorical/spiritual door: “It’s time we start smiling/What else should we do?” And “Let It Down” is a tremendous climax to the first album, with its gargantuan, broad intro (which clearly predicates T. Rex’s “Children Of The Revolution”) unexpectedly diverting into a churchy organ and pensive electric guitar which could have come straight out of prime period Pink Floyd (indeed, some claim that Richard Wright was an uncredited keyboardist on this and other tracks). Here Harrison does his utmost to open up; he’s sitting in that chair, but don’t think he’s not feeling what you feel, or that he doesn’t want to touch you – is somebody trying to look at him? The music, however, has no doubts whatsoever; Clapton’s stormy leads throughout the choruses, contrasting with his suspended animation chords in the verses, are akin to curtain rails being yanked down, the barriers being brusquely removed. Processed guitars acting as effective string sections are deliberately wobbly – Gary Brooker’s bluesy piano now the only recognisable signifier – in such a floating, centre-free way that again presages My Bloody Valentine, Spector here taking the opportunity to develop the ideas he’d laid on the table with his Checkmates Ltd work.

The first album ends with “Run Of The Mill”; a clean acoustic guitar interacts with loitering, shoulder-shrugging brass as Harrison glumly reprimands a lost friend – probably representing McCartney – for losing touch, for finding ways to blame everyone but himself, waiting to be offended. It’s a regretful reproach rather than an acrid demolition – the latter would have to wait until Lennon’s “How Do You Sleep?,” later in 1971 – and we are left with the feeling that the sixties, and the Beatles, and everything they represented, are as far away and irretrievable as ever.

Album two opens with “Beware Of Darkness”; an abrupt introductory crescendo quickly gives way to sad chords – slightly reminiscent of “Maybe I’m Amazed,” which had premiered on McCartney in the spring of 1970 – as Harrison remembers the “falling swingers dropping all around you” (Hendrix, Joplin, Jones; the ghosts were piling up already) and warns us against following their example. He pressingly urges us to “beware of MAYA,” the Hindu wall of illusion which bars us from dealing with the real world, and warns about all the factors in this world (especially “greedy leaders”) who lurk, waiting to do us down. Something of the schoolteacher has entered the proceedings at this point. “Apple Scruffs,” in contrast, is an affectionate and really rather touching epilogue to an era, with its very Dylanesque acoustic song structure and angular harmonic multitracks in the chorus; he is a long way from Abbey Road now but the umbilical cord remains as unbreakable as ever.

“Ballad Of Sir Frankie Crisp” – the latter was the architect of Harrison’s residential castle – floats along nicely enough on its oceanic bed of pedal steels and “A Day In The Life” piano but the Pythonesque Spenserian lyrical conceits and the rather incongruous reappearance of the “let it roll” motif from “I’d Have You Anytime” do little to suggest that this is anything other than the indulgence of a rich man, albeit in conference with his self-affixed ball and chain; he can roll out as far into the countryside as he wishes, but can he really escape himself?

“Awaiting On You All” is a vast improvement, essentially setting the template for what would, after the sessions for this album, become Derek and the Dominos, and Spector’s magisterial production – compare with the Dominos’ original version of “Tell The Truth” - fits the song’s gospelly overkill perfectly, thumping through regular stops, starts and dead ends like a sprightlier, less apocalyptic “River Deep, Mountain High,” although the chorus does bear a strange resemblance to that of the Carpenters’ “Superstar.” Side three closes with the title track, in which, over pedal steel and strings, Harrison reinforces his departure from his previous life (“I must be on my way”); he tempers the apocalyptic fury of the passage from the Book of Matthew which gave the song and album its title but note how Drake’s guitar slides up to its piercing height, expressing an unquenchable sorrow. Throughout, a remorseful guitar and brass six-note unison refrain pace like patient pallbearers.

Meanwhile, Harrison begins side four by announcing that “I dig love,” and, moreover, “I love dig.” The song is gloriously silly – perhaps a Lennon pastiche was in mind – with an insinuating riff which sounds like the Humphrey Lyttelton Band attempting a Motown intro (there is an incongruous pedal steel audible in the spaces after the second chorus – is Pete Drake the secret hero of this era?). The lyric references “Come And Get It,” the music suggests the outskirts of “Come Together,” but its frivolity comes as something of a relief after the intensity of the previous three sides; we were reminded of “The Girls” by Calvin Harris – the same list-ticking (“Left love, right love, anywhere love”), the same bemused grin which the singer bears.

“Art Of Dying” initially comes across as a riposte to “Let It Be” – “There’s nothing Sister Mary can do” – until one remembers that McCartney sang of “Mother Mary” and that Harrison wrote the song in 1966 but didn’t submit it for Revolver, given Lennon’s more acute take on the same subject with “Tomorrow Never Knows.” Clapton reintroduces a chattering wah-wah, and the general musical tone is, of all things, Blaxploitation, with blasting horns and real funk, although the Mariachi trumpets suggest Tom Jones having a go at “Superfly.” The bassline predicates Paul Simon’s “Kodachrome” and overall it’s a brilliant panoply of sound – somewhere in the mix, a nineteen-year-old Phil Collins is thrashing a set of bongos – as Harrison implores us to face up to the unfaceable.

Then it’s back to “Isn’t It A Pity” as a quietly imperious coda to the album, taken at a lower key and performed in a slower, more reflective manner than Version One. Piano, guitar and pedal steel blend empathetically, and the line “Some things take so long” might be the key to the entire album. The song sadly rolls up to a Floydian climax, although Harrison’s vocal here can be construed as more demonstrative, angrier – this is how Harry Nilsson, devoid of sentimentality and dimes owed, might have approached the song. Finally “Hear Me Lord” comes in on a thunderous introduction, giving way to rueful piano and drums. Here Harrison makes his final imprecations to God, begging Him to rescue him from earthly concerns – the cut-in “Above and below us” sequences play like an interrupting commercial – while Clapton is majestic, and the brass and chorus offer a grey elegy. After a pause the song reaches its final destination, and Harrison utters a plea to his Lord to “burn out desire.” The state of “burning out desire” is, of course, Nirvana, and I cannot help but hear the premature ghost of Cobain in his careful wailing; this is a doubtful ending to an uncommonly intense experience of a record.

Most listeners consider All Things Must Pass as finished here, but I must demur; the Apple Jam disc of jam sessions is very far from an inessential bonus. If anything, these instrumental workouts do a vital job in summing up and dispersing all of the tension that has been building up over the previous four sides; “Out Of The Blue” is as intense as any of the previous songs, a long, troubled minor key blues, slightly detoured by piano and organ, but almost completely dominated by Clapton’s astonishing playing – the track cuts right in, as though we have suddenly opened the door in the middle of a quarrel. But it articulates all of the hurt and doubt with which Harrison’s words have hitherto attempted to come to terms.

From there, we move straight into “It’s Johnny’s Birthday,” Harrison’s audio birthday card to Lennon for his thirtieth, with its mad, varispeeded Wurlitzer variations on Cliff Richard’s 1968 Eurovision runner-up “Congratulations”; this has the effect of upping the record’s mood instantly, and segues straight into the major key, celebratory workout of “Plug Me In,” Harrison working well with fellow guitarist Dave Mason before the track happily scrambles to a halt.

“I Remember Jeep” is a frantic but good-natured quartet improvisation by Billy Preston, Klaus Voorman, Ginger Baker (instantly making his presence felt – those frenetic, barline-spilling cymbals) and Harrison, which culminates in a round of studio applause but is prefaced and punctuated by bizarre Moog bleeps and whooshes which seem to provide the missing link between Joe Meek’s I Hear A New World and Carla Bley’s “Phantom Music”; these were sampled from Harrison’s experimental 1968 album Electronic Music and provides an aura of welcome strangeness to the otherwise fairly straightforward proceedings. Finally, Harrison and Mason return, in “Pepperoni,” to invent Status Quo, and the spirits are now so generous we hardly notice the abrupt cutoff at track’s end; here we can sense that Harrison has finally found himself after four sides of agonised self-searching – he’s doing exactly what he wants to do, playing for fun with his mates, with no hassles, no obligations, and he loves it. As with the merrily orange cover to the Apple Jam disc, we find that true colour has finally returned to Harrison’s black and white world, and that this, the first solo Beatle disc to appear in this tale – not to mention the first, and certainly not the last, triple album – finds himself home, with the lights on, and the smile subtly returning under that pesky beard.