Tuesday, 4 May 2010

Bob DYLAN: New Morning

(#86: 28 November 1970, 1 week)

Track listing: If Not For You/Day Of The Locusts/Time Passes Slowly/Went To See The Gypsy/Winterlude/If Dogs Run Free/New Morning/Sign On The Window/One More Weekend/The Man In Me/Three Angels/Father Of Night

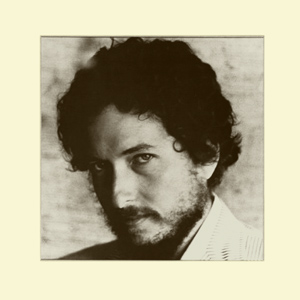

Look at that expression, and try to figure it out. On first sight he looks contented, satisfied; that Self Portrait was a mere diversion, a kid-on, here I am back again, this time for some serious business. But there is a knittedness to his brow, as indissoluble and intangible as the fine cut of his jacket. This isn’t quite a return to where I was, he is warning; this might even present greater challenges than what I’ve already laid down before you.

New Morning was an early example of what has in rock criticspeak become known as the phenomenon “a stunning return to form.” That is to say – more often than not - a reassuring retreat to an artist’s best recognised mannerisms, some crumbs of formula to toss towards an anxiously impatient audience. Everyone drew gulps of canyon-sized relief when the album came out; OK, Bob, we knew you were only fooling around with those four crazy sides in the summer. Everyone called it a classic until the mist cleared from their eyes and they were presented with a Dylan who still wasn’t quite giving them what they wanted, despite the return of the whine, the harmonica and even Al Kooper. On the rear cover a young Dylan, curling his lip in an attempt to be Elvis, is standing beside an approving Victoria Spivey – he contributed some harmonica to a 1962 collaboration on record between Spivey and Big Joe Williams – looking as though he already has the blues licked, now that he has its approval. The studio pictures included in the CD edition could easily come from 1962, too, although Dylan and his band are clearly enjoying themselves.

“If Not For You” starts the record, along with knitting needle drums, childlike glockenspiel and a brightly-spun David Bromberg guitar line. He is singing about relief and salvation but sounds a little too desperate for comfort – Olivia Newton-John had her first major international hit a few months later with her smiling and very uncomplicated reading of the song, and we will be returning to it in the form of another less quizzical version in a couple of entries’ time – snarling at times (“Wait FORRRR the morning light!”), generally hoarse to the point of losing reason altogether; his “Without your love” is as exhausted as the average Beckett protagonist. “Anyway,” he almost shrugs the whole song off, “it wouldn’t ring true.” The song’s direction is open; he could be singing about a lover, or a child, or to God, but he sounds as though clutching straws of reed in order to breathe; he sings about a falling sky, gathering rain, springless winters and an abandoned soul deaf to the song of the robin – hardly a sunny welcome back to his listeners.

“Day Of The Locusts” is an advancement of the old Dylan talking blues template; commencing with stentorian piano (played by Dylan – I can’t think of too many other Dylan albums where the piano, especially his own, is so prominent) joined by judgmental drums and organ. He’s at Princeton, reluctantly, to accept an honorary degree (“I put down my robe, I picked up my diploma”); after hellish visions of exploding heads, dark tombs filled with judges, he is enlightened and elevated only by the strange hum of locusts – he makes their “sang” sound like “stings,” and the bass drum instantly kicks back. As he and his sweetheart retreat to the black hills of Dakota (“Sure was glad to get out of there alive”) his tone becomes more euphoric, the piano and drums more ringing and celebratory (a great performance from Russ Kunkel and/or Billy Mundi at the drumkit).

“Time Passes Slowly” begins with a McCartney piano staccato figure (“Penny Lane” etc.) before turning into a delicate piano and drums waltz; there’s a lovely chord change (E to D) after the first “time passes slowly” and guitar and dobro intertwine like lovers, but it’s unclear whether Dylan is simply contemplating the simple, peaceful life or lamenting its absence; “Once I had a sweetheart” he remarks, and elsewhere he concludes, not exhausted but conclusive, “Ain’t no reason to go anywhere.” “We stare straight ahead and try so hard to stay right” – these could almost be the ghosts of former lovers which haunt Walker’s “Always Coming Back To You.” The song, as with many on the album, seems to break up organically; the record frequently carries the air of not quite finished demos.

“Went To See The Gypsy” bases itself on a very closely knit pattern of low register piano, bass, organ and drums. Like the hapless boy in Joyce’s “Araby,” he is seeking something, or someone, fundamentally unattainable; Dylan’s delivery, however, is deliciously deadpan (“I said it back to him,” “Bring you through the mirror”) as he encounters the “gypsy” in his “big hotel” with his dark room and low lights; the references to the dancing girl and Las Vegas – the music audibly squeals with relief at the couplet “He did it in Las Vegas/And he can do it here” – suggest Elvis, although the shadow might well be Hendrix, he of the Band of Gypsys. In any case, the return visit finds the expected emptiness, and instead of nirvana, Dylan finds himself back where he started – “that little Minnesota town.” The music, however, treats the return with tickertape as Bromberg’s lead guitar speeds the song up to boogie tempo.

“Winterlude” is a lovely petit parlour waltz, where Dylan returns to his “crooner” voice – as his most recent entry in this tale (at the time of writing) will demonstrate, he has never really abandoned it – with light and funny lyrics; the invitation to “go down to the chapel/Then come back and cook up a meal,” the various “dude” rhymes (“don’t be rude”), balanced with the simple plaintiveness of “thinks you’re fine” and the references to angles and fire logs. Snowflakes cover the sand; winter is coming and not for the first or last time on this record; the subtly mixed female backing vocals bring Leonard Cohen to mind. The music is glossy, swimming, guitar dovetailing into dobro and piano. The whiteout is bringing unexpected comfort.

Side one, however, concludes with the record’s, and possibly Dylan’s, least typical track – and “If Dogs Run Free” sprints with languorous liberation. Kooper hammers out an intro on piano before he and the rhythm section settle into a Teddy Wilson-derived blues. Dylan ponders on human freedom, unanticipated leaks of Wordsworthian grandeur (“Oh, winds which rush my tale to thee”) and the placid conclusion that “true love needs no company” in a double-bluff throwaway manner which invents Tom Waits. But what really catches the ear is what backing singer Maeretha Stewart is doing behind him; as Kooper’s piano nags at the upper register like a hyperactive Westie, Stewart does some ebullient bebop scatting which soon goes rather further out, in both rhythm and tonality. As the band wriggles out of Dylan’s “and that is ALL!,” Stewart gurgles and yelps as though auditioning to replace Leon Thomas in Pharaoh Sanders’ group. It was the lightest and most applauded track on the album.

We keep coming back to lightness; much of New Morning was improvised on the spot, and Dylan himself has tended to dismiss it as semi-directed hackwork. Some of it, however, came out of shells of songs which Dylan had planned for Scratch, Archibald MacLeish’s doomed musical version of The Devil And Daniel Webster, and the title track was one of these. Guitar and drums, again, are bright in the most welcoming of ways, but the organ which hovers dangerously underneath the song’s slightly regretful bridge (and Dylan’s somewhat foreboding“automobile”) – like Mr Scratch lurking, ready to make sure Webster keeps his part of the bargain – suggests escape from unspoken menace. Kooper’s organ galumphs and hisses over Dylan’s first “sky blue” and there’s a terrific crescendo of guitar, organ and drums at his “When you’re with me” which naturally leads to Kooper’s calming French horn (you can always get what you want?). There is real ecstasy in Dylan’s disbelieving “So happy just to be alive/Underneath that SKY of BLUE!,” the emotion of which is quite overwhelming in its hoarsely passionate assurance. Wake up on brilliant days, indeed, ones which even the Devil can’t haunt.

Rubato piano introduces “Sign On The Window” and we move straight into gospel; Dylan sings of a couple heading to California, becoming disillusioned (“Brighton girls are like the moon”), then settling for a cabin in Utah. The signs whose content Dylan proclaims are as absent of humanity as any of the signs in the Village (“Lonely,” “No Company Allowed,” “Y’Don’t Own Me,” “Three’s A Crowd” – it tells its own profound story) but something in him is determined to ensure that it will work, no matter how lowly the circumstances; the sublime and completely unexpected shift to E major after “Looks like a-nuthin’ but rain” practically demands that you hope, succeeded by a contrasting, harmonically ambiguous dobro, guitar and backing vocals sequence; he says he’ll settle for the cabin, a wife and kids – “That must be what it’s all about,” he says to himself twice, convincing himself that it is, and by the way he hangs on the vowels of his extended “sleeeee-ee-eep,” he is probably convinced.

New Morning is an adult record – “Sign On The Window” might be the first non-stage musical/MoR song in this tale to speak explicitly of families – and was not designed for those still wishing the adolescent atomisations of his younger days; “One More Weekend” is a straightforward hangdog blues workout, Kooper’s piano sliding exactly “like a weasel on the run,” about the joys of getting away from the kids for just one weekend. Bromberg responds with a strong, groaning, quivering guitar performance, like Hubert Sumlin transposed to Nashville; the mood is definitely upward.

But then we come to “The Man In Me,” one of the album’s briefest yet deepest meditations. Dylan’s absent-minded “la la la” intro is bewitching in itself, especially when going into call and response with the backing singers and Kooper’s Morse code organ, but the song’s processional is solemn, midtempo, rather like “The Weight,” although he is clearly happy (“From my toes up to my ears”) despite the storm clouds raging all around his door; he knows how close he’s come to giving it all up but now nothing could be further from his mind. “He (as in “Man”) doesn’t want to turn into some machine” he proclaims (see also Stevie Wonder’s recently discussed “Never Had A Dream Come True”), but there’s a rare beauty in his invocation of Oklahoma! – “But oh what a wonderful feeling” – as he recognises how much she’s saved him. “Took a woman like you/To get through to the man in me,” he sings in quiet awe as Kooper hushes his organ to shades of ethereality, and I am reminded of Marvin Sapp’s recent, barnstorming “The Best In Me” (from Sapp’s album Here I Am, the strongest gospel album in some time) where he spends seven minutes singing to his Lord of the same thing, the same nature, in gradually unfolding petals of euphoria. The joy is universal, shared, and godly.

“Three Angels” takes three bums, or maybe it’s just three scruffy musicians he notes on the street, and elevates them into holiness. The tempo is slow, R&B ballad 6/8; Dylan talks most of the song, Kooper’s organ is awaiting ordination, he sings of bright orange dresses, U-Haul trailers, the Tenth Avenue bus, wonders “But does anyone hear the music they play? Does anyone even try?” Beside him, the chorus and song have gradually gathered strength; the awesome chord change on “Does anyone even try?” blossoms, shockingly, into a sequence of hard, stately rhythm and choirs which seems to want to segue into “Atom Heart Mother.” As with the rest of this album, nothing much seems to happen, but no one notices angels when they are right next to them.

The struggle of New Morning finally comes down to the old American conflict; the glory of the bounty of their land, mixed with the suspicion that something else must be happening – this can’t all be for our benefit? – that there is something, someone, higher and more powerful. Dylan doesn’t offer answers – he is Dylan, for heaven’s sake – but simply concludes the record with a reconfiguration of Amidah, the central prayer of the Jewish litany, with Dylan at the piano, accompanied by his backing singers (together providing a great three-chord/three-note leitmotif), knowing that this is not the place to describe the indescribable but merely setting out his path, some nine years ahead of Slow Train Coming. New Morning is a friendly record, certainly, but it’s also a heavily guarded one and in its implications perhaps invites more radical recasting than anything attempted in Self Portrait. “Father, who turneth the rivers and streams” – if not, it might be concluded, for Him.