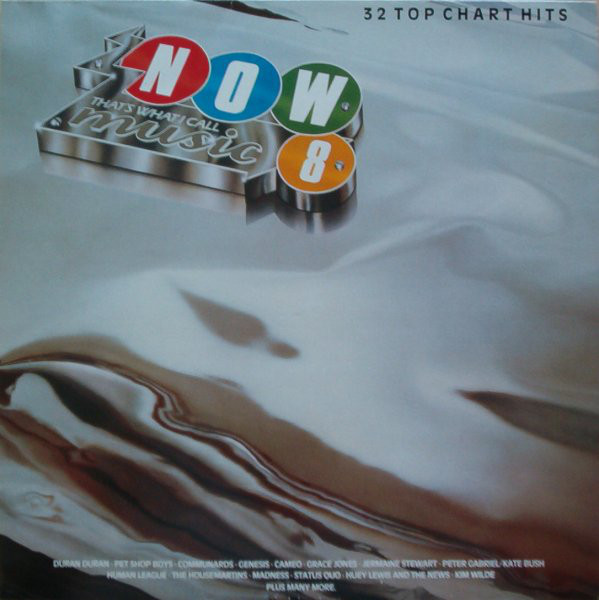

(#339: 6 December

1986, 6 weeks)

Track listing:

Notorious (Duran Duran)/Suburbia (Pet Shop Boys)/Walk This Way (Run-DMC)/Don’t

Leave Me This Way (Communards)/Breakout (Swing Out Sister)/Higher Love (Steve

Winwood)/Forever Live And Die (Orchestral Manoeuvres In The Dark)/In Too Deep

(Genesis)/Word Up (Cameo)/I’m Not Perfect (But I’m Perfect For You) (Grace

Jones)/Showing Out (Get Fresh At The Weekend) (Mel & Kim)/We Don’t Have To

Take Our Clothes Off (Jermaine Stewart)/Step Right Up (Jaki Graham)/What Have

You Done For Me Lately (Janet Jackson)/Human (Human League)/I Want To Wake Up

With You (Boris Gardiner)/Don’t Give Up (Peter Gabriel/Kate Bush)/Think For A

Minute (The Housemartins)/(Waiting For) The Ghost Train (Madness)/In The Army

Now (Status Quo)/Stuck With You (Huey Lewis and The News)/One Great Thing (Big Country)/Greetings

To The New Brunette (Billy Bragg)/(I Just) Died In Your Arms (Cutting Crew)/You

Keep Me Hangin’ On (Kim Wilde)/Calling All The Heroes (It Bites)/Waterloo

(Doctor & The Medics with Roy Wood)/French Kissin’ In The USA (Debbie

Harry)/I Didn’t Mean To Turn You On (Robert Palmer)/The Wizard (Paul

Hardcastle)/(They Long To Be) Close To You (Gwen Guthrie)/Every Loser Wins

(Nick Berry)

Although some of you might imagine that I’ve been a chart

geek all my life, forever writing down this week’s Top 40 and filing it away, I

have to disabuse you of that notion. There have been times when I have drifted

away from the “Fun Thirty” or “Pop Forty” for extended periods and for various

reasons. These can be summarised as follows:

- August 1972-October 1973: I had been religiously following the charts since 1969 (to cries from the gallery: “oh, come OFF it MC, you would only have been five!” Indeed I would have been. I was a child prodigy. Deal with it. Who was the greater Melody Maker writer of the later sixties – Bob Dawbarn or Bob Houston?) but in the summer of ’72 I got a bit bored with the charts and weaned myself off the music press. The main reason for this gradual ennui was that there were plenty of other things to distract me – comic books (American, British and French), wacky, surreal television and radio comedy, week-by-week science encylopaedias. I got into the pop thing again by listening to Paul Burnett counting down the Radio Luxembourg Top Thirty of a Tuesday evening (then sponsored by Peter Stuyvesant cigarettes!) and via that I hooked up again to the BMRB listings. By Christmas of 1973 I was back on Record Mirror (which gave you the full Top 50 plus breakers!), MM, Disc and Music Echo, NME and Sounds. Not to mention monthly or bi-monthly glossies (they weren’t really) like Street Life, Let It Rock, Blues And Soul and the week-by-week Story Of Pop encyclopaedia. It’s a wonder I had any time left to do my homework really.

- After that I carried on following the charts until the summer of 1979. Ironic, really, when you consider that 1979 was one of the finest years the charts had ever known, and it certainly wasn’t down to a sudden disinterest in music – quite the reverse; I continued to devour the music papers, but for some reason the charts didn’t seem so relevant to me that I had to stick to, or by, them. Every Saturday was an adventure – you’d go to 23rd Precinct in Bath Street, then the two Bloggs shops, one in Renfield Street and the other in St Vincent Street, then Listen Records a little further down Renfield Street, then HMV in Union Street. Plus the second-hand exchange shop at the bottom of Jamaica Street, Iona Records for folk and jazz in Stockwell Street, James Kerr & Sons in Woodlands Road for jazz and classical, and the other Listen Records branch in Byres Road which you could clearly see in the distance, descending down Gilmorehill from the University.

But I think my growing apart from

the charts was down to the way they were presented in the media, in particular

the BBC’s (as we now know, highly questionable) view of pop being that of BA

Robertson, Dr Hook and the Dooleys. This suspicion was confirmed by re-viewing

of a 1979 TOTP episode last week,

which featured musical groundbreakers of the calibre of Randy Vanwarmer and

Bill Lovelady (with a leather-clad, unfortunate T-shirt-wearing Cliff at number

one, looking and moving surprisingly like Jim Morrison). That was not something

with which I felt comfortable, and so I kept up but opted out, only coming back

in around November 1980.

- Thereafter I rekindled my Top 40 interest until September 1986, when I absented myself from listening to, or really caring about, the charts for a few months, for personal reasons which are none of your business. Once 1987 dawned, I was back in, and stalwartly stayed with the charts until the mid-nineties point (I can’t pinpoint a precise time or date) when it had become fully apparent that the charts had been reduced to a battle of marketing strategies, rather than a list of music that people genuinely liked.

But the point is that the music heard on Now 8 coincides with that period of

abstinence in late 1986, and it may therefore be that I was able to approach it

with a less jaded ear. Certainly as a compilation it hangs together a lot more

coherently than Hits 5, and despite

still containing quite a fair amount of drivel, does give a clearer picture of

the radical changes which were beginning to affect the charts – and pop –

during that period (but would only really, if dramatically, become apparent in

1987).

That having been said, somebody in the Now organisation was reluctant to give up the one-size-fits-all

ghost, and so the album contained a competition in which you were given three

ridiculously easy questions to answer – the answers are, in order, (A) Madonna,

(C) Phil Collins and (C) A Pig, but as the closing date was 28 February 1987 I

don’t feel I’m breaching any rules by telling you. The prize, however, was a

very decent one – 86 albums (in whatever format) of your choice from “a leading

London record store” (HMV?), plus the chance to see a record being manufactured

and a visit to the Abbey Road Studios. What I could have done with eighty-six

albums of my choice at a time when you could buy just about any album you

liked, despite the sinister Wonka-esque orders: “H.O.W. TO ENTER…DEAD EASY,” “So…Go

On…Do It Now…” I’ve no idea who actually won, but trust that he or she remains

very happy.

But what about the music,

Mr Infinitely Drawn Out And Endlessly Dreary Preface, No Wonder You Can’t Get A

Book Contract, Who Do You Think You Are, That Hilary Mantel Off The Telly Like?

All right, I’ll get on

with it:

Chic

And then there were three, and it was their best record in

years, despite the lyric’s endless go-having at the messily-departed Andy

Taylor (“Lay your seedy judgements,” “Don’t ask me to bleed about it”). Nile

Rodgers produced and played unmistakable guitar, and unlike Let’s Dance the music sounded taut and

whole, like a group of musicians playing in the studio rather than across a

huge, dry billboard. So they finally got to be Chic, of sorts, and the

entertainingly bitchy lyric could be Lydon having a crack at McLaren. Moreover,

the album contained the finest song of their career, “Skin Trade.” But they had

been away, or atomising, for too long, and despite the Now people’s confidence that this would streak to number one, it

peaked at number seven, and the album didn’t get beyond #16. The Melody Maker reviewer remarked that if

Duran had really been hip they would have hired Rick Rubin. However, the

overriding picture was one of expensive music being made by and for rich

people.

Sweet Suburbia

The primary inspiration for the song was Penelope Spheeris’

1984 movie Suburbia, which was set in

Los Angeles and introduced Flea to the world, but the Pet Shop Boys also had

the Brixton riots of 1981 and 1985 very much on their minds. The original

recording, as heard on Please, is

comparatively mild-mannered and more in keeping with Ballard’s Shepperton than Spheeris’

Interstate 605.

But the duo re-recorded the song entirely for their Disco remix album and abolished all

British restraint. Driven by huge piledriver beats, we hear breaking glass, dog

barks, police sirens and general noises of rioting; at times it’s a wonder that

the song manages to make itself heard. “I only wanted something else to do but

hang around,” Tennant whimpers while the world explodes around him, and this is

the flipside to both nouveau and riche; the self-inflicted punishment

endured by those whom the revolution left out, or left behind. “Where’s a

policeman when you need one/To blame the colour TV?” Money for nothing, indeed,

and it worryingly hasn’t dated an atom. And it is not the only song on this

record which warns that “You can’t hide.”

Walk Another Way

The story is that, while recording Raising Hell, Rick Rubin produced a copy of Toys In The Attic and asked Run-DMC to freestyle over it. The group

knew nothing of Aerosmith and could have cared less about “Walk This Way” but

they were persuaded to record it and hence resuscitate Aerosmith’s career

(their 1985 “comeback” album Done Without

Mirrors might as well have been titled Done

Without Sales) plus breaking down alleged MTV barriers and so forth.

Now Raising Hell

is, if anything, a whole lot more unrepentantly minimalist than its two

predecessors – it is, essentially, beats and voices – but if you regard the

story of 1986 as beginning with Radio

and ending with Licensed To Ill then

it makes perfect sense; Rubin’s idea with Def Jam was that it should be

contemporary rock ‘n’ roll, and if you take into account Chuck D’s belief that

hip hop should be listened to while on the move, preferably driving a car,

because it then offers a dimension which is absent when listening to it at

home, then Raising Hell was just what

pop needed. I can’t drive, but I did travel a lot around Britain in 1986, and

the album was released in Britain a couple of weeks before the Edinburgh

Festival; I greatly enjoyed sauntering down Rose Street with “My Adidas” or “Peter

Piper” blasting within my earphones and imagining that I was the hippest guy in

Britain (or at least in Edinburgh).

I still have that cassette, but hardly listen to it now.

Back then I’d just groove to the grooves and try to pretend “Dumb Girl” didn’t

exist, but these days it’s harder to do that. Steven Tyler was already too old

to sing the locker-room come-ons of “Walk This Way” back in 1975 and it’s

impossible to imagine the song getting through now; to listen to it is as icky

as thinking of the video to “…Baby One More Time” and everything that has since

caused or attempted to justify. Yes, it’s top-notch rock ‘n’ roll. But that

implies that top-notch rock ‘n’ roll is enough, and I’m no longer sure that it

is.

The Communards with

Sarah Jane Morris

As I’ve already said, in August, as "Don't Leave Me

This Way" was climbing up the chart, we were at Edinburgh for the Festival

(and mostly for the Fringe) and watched a superb concert by the Happy End, who

were a sort of deliberately ramshackle socialist big band mixing up Brecht,

Bley and Brotherhood of Breath. They released a couple of albums, which were

fair, but really they needed to be experienced live. Their best and most

imaginative soloist was tenor saxophonist Sue Lynch, but altoist Adrian Northover

subsequently became a core member of the London Improvisers’ Orchestra. Their

singer was Sarah Jane Morris, a tall, gangly redhead with a penchant for hats,

earrings and tunics, and she skipped excitedly through the semi-improvised

melee, suddenly breaking into "My Baby Just Cares For Me" but putting

great emphasis on "she" and "her." Her subsequent solo

cover of "Me And Mrs Jones" unsurprisingly had radio programmers

running fervently in the opposite direction.

You can therefore tell how the balance worked in terms of

Sarah Jane, the tall, deep-voiced gay singer, and Jimmy Somerville, the short,

falsetto-voiced gay singer, and how such a combination, in tandem with an

instantly recognisable anthem from more innocent times, would have led to

1986's best-selling single. Certainly few artists deserved a number one more

than Somerville; unapologetically militant and passionate about his sexuality

and politics, and with an utterly individual style, but with an audience not

(yet) too interested in original Communards songs. So he and Richard Coles

needed a hit – in mid-1986, Bronski Beat Mark II with John Foster were

commercially way ahead – hence the cover version.

Former Soft Cell producer Mike Thorne was at the helm for

"Don't Leave Me This Way," and it's an agreeable enough romp through

the Gamble/Huff standard, with Somerville and Morris' voices dovetailing well

into and out of each other, essentially assuming each other’s gender, and a few

nice production touches - the backwards bassline in the mid-section breakdown,

the piano motif which uncannily foretells that of “Orinoco Flow,” and the mountain-scraping

"aaaaaaaaahhhhh!" which leads to the final key change. Of course

there was an unavoidable subtext to the Communards’ performance, and so there

was something deliciously subversive and righteous about this record outselling

everything else in its year. A pre-emptive NO to sectioning.

Breakout

They were initially a splinter group from A Certain Ratio,

and the opening of “Breakout,” wherein a curtain of desolate Joy Division

synthesiser sweeps open tor receive the warm welcome of Corinne Drewery’s voice

and Richard Niles’ horns, signifies the closing of an old book and the opening

of a new one. The song should be heard in tandem with ACR’s terrific 1986 album

Force, to which both keyboardist Andy

Connell and Drewery contribute, and in particular the fabulous “Mickey Way”

which helped Manchester music see the direction through to the next decade.

Martin Jackson, once of Magazine, was on drums, and “Breakout”

is an elegant call to arms, politely calling for insurrection (“Lay down the

law/Shout out for more”) and asking its audience to hurtle on out of the

darkness (i.e. of Curtis, Thatcher and the past in general) and create

something new and colourful. “Some people stop at nothing,” sings Drewery; the

implication being, so should you.

Sighted Faith

Absent from Then Play

Long since 1969, it’s a real pleasure to welcome Steve Winwood back. “Higher

Love” is as professionally put together (Winwood co-wrote with Will Jennings

and co-produced with Russ Titelman) as anything by Phil Collins, but there’s a

far looser and more becoming swing in Winwood’s approach, and from the lyric (“There

must be someone who’s feeling for me,” “In this whole world, what is fair?”) he

could almost be the object of “Breakout,” the lost, confused soul waiting to be

led back out into the light. Unlike Collins’ work there is also a greater

degree of hope; “Addicted To Love” had originally been planned as a duet

between Palmer and Chaka Khan, but the latter instead made her way onto here,

and her sustained yelps of joy and comfort suggest a happy ending. The video

was almost exactly identical to, and directed by the same directors as, the one

for “Notorious,” yet the two songs couldn’t be further apart – the missing link

between the two is Talk Talk’s “Happiness Is Easy,” from The Colour Of Spring, on which Winwood plays organ.

The Pacific Age

Another OMD song sung by Paul Humphreys, and with something

of Nancy Wilson’s “How Glad I Am” in its matrix, “(Forever) Live And Die” was lyrically

as determinedly obfuscatory as ever, but the old angelic yearning was back,

along with some less welcome mid-eighties brass stabs (its predecessor, “If You

Leave,” had been a huge hit everywhere except Britain). Producer Stephen Hague

makes the chorally-multitracked Humphreys sound like Neil Tennant’s generous

uncle, and the song itself is already suggesting the Atomic Kitten to come.

Mona Lisa

…is the film with which I most readily associate “In Too

Deep,” soundtracking as it does a miserable Bob Hoskins ambling down Berwick

Street on an unlovely weekday morning searching for Cathy Tyson. But while

Collins admits “it may be my fault,” he may not be implying “for being stuck in

a complicated gangster set-up with little-things-noticing Michael Caine.” The

song appears to draw a line under a “Me And Mrs Jones” scenario – he loves her

but he’s married to someone else and knows where his duties lie – without reiterating,

or even implying, Gamble and Huff’s Watergate subtext. A nice keyboard

interlude which strives to be OMD but actually drags me back to the cloak of

loneliness that was 1978’s “Many, Too Many.”

New Pop!

In which Cameo finally bloomed into splendid velveteen

pantaloon glory. “Word Up!” was another one of those unspeakably brilliant pop

singles which I played ninety-five times in a row without once getting sick of

it. Blackmon outraged TOTP parents

with his red codpiece, but more importantly he and his band knew what time it should be. From the similarly-titled album,

this, “Candy” and “Back And Forth” form a sublimely insolent pop sequence which

I know I loved because it reminded me of the Human League – do you detect the

spirit of “The Things That Dreams Are Made Of” beneath “Word Up!”? The celery

stick drumming. The Morricone whistling. The Meek keyboards. The final,

gloriously inevitable work-up to the entry of the Brecker Brothers. The album

got boring and humourless after those first three songs – please try to pretend

that “She’s Mine” never happened – but “Word Up!” is a stupidly genius YES! to everything

that the pop around it should have been.

Grace

Inside Story

contained no “Slave To The Rhythm,” and not much in the way of songs beyond its

single (co-written with one-time Trevor Horn associate Bruce Woolley), but “I’m

Not Perfect” is pretty fine in its own right; the second Nile Rodgers

production here, and something of an anti-“Notorious” with a weirdly atonal

choral drone hanging in the background like a lost, submerged Boney M album. On

the title song she sings, “How great thou art/How great IS art!” How many other

people in 1986 were even THINKING that?

The Glory Of Mel

& Kim

Edited excerpts from writings at the time (as mentioned

above, I travelled a lot in 1986, chiefly between Glasgow, London, Edinburgh

and Oxford):

“The M25…resplendent in the brightly lit darkness…the

promise of something new and sexier to come…this is the future with a thumping undertow

of brutalism…but London, LONDON!...what a place to come to…what a place unlike

the one I came from…it completes the picture…somewhere past Crewe…you feel the

North morphing into the South…the land becomes flatter, the houses more

prosperous…and the bangs, the BANGS on the Walkman…perfectly echoing the

rapidly disappearing chevrons of the motorway…obscure service stations…will I

wake up and find myself glaring at Blackpool Tower in the darkness?...not as I

knew it in the seventies…down here are love, hope and tomorrow…up there, well

it’s just yesterday…but you feel the difference coursing through your body…like

the difference between Vimto and vodka…bang out those beats…Janet Jackson…Jam

and Lewis…Sigue Sigue Sputnik…make total sense out here, fifty miles from

Birmingham…Diamanda Galas, The Divine

Punishment…expression of a pain which cannot and will not be suppressed…Tackhead…”Hard

Left” and “Mind At The End Of Its Tether”…”In a free country, everyone has to

CHOOSE”…”Sightsee MC” by Big Audio Dynamite…”Captain Scarlet is indestructible”…House,

House music, that conga effect that gives a bit of bitonality…Mel and Kim…what

a name…what a pair…the sound of working-class Hackney via Jamaica…”Sh-Sh-Showing

Out”…the first British pop record to take House music seriously and assimilate

it…Stock, Aitken and Waterman…they will be hated but they are New Pop and they

will be proved right…apparently Bananarama had first refusal on the song but

you KNOW Mel and Kim had to do it…shrieking, stuttering drum programmes, an

awesome, ominous SWEEP like the Post Office Tower hiding behind your Christmas

tree…them and the Age Of Chance, you need them both for this year of years…”You’d

better live in love than luxury…that’s

alright”…I read somewhere, or maybe just imagined it, that Waterman said

that “Showing Out” was what he’d liked to have done with Five Star….that Melody Maker interview where one of the

Pearsons said she couldn’t possibly go out with somebody who earned less than

£50,000 a year, in 1986 money…but this is a Fosbury flop into tomorrow…and yet

it is an ANTI-CAPITALIST SONG, all about how love is much more important than

money (“Can’t afford to wear diamond and pearl, that’s OK/Wouldn’t want to be

that kind of girl – ANYWAY!”), about how the life is all about now and that’s

all we have…the Tavares paraphrase just before the chorus…there’s a bloody

HARPSICHORD in the chorus!...the minor key undertow suggesting an underlying

darkness…and yet the middle-eight, harmonies and everything, could have come straight

out of Linx!...so the song just shakes itself to pieces, because that’s what

pop in 1986 has turned into, a gigantic jigsaw puzzle…look there’s Brent Cross

OH off the motorway and down the hill!...cold Aids iceberg posters…Finchley

Road tube, blue and serene in the erratic rain…in the centre of everything…knowing

that this is now…so much more fun than what you knew before…and you know deep

down it is wrong and illusory…this Thatcher town…but you end up attracted by

the lights anyway…thudding…England’s motor…Scotland’s pain…Maida Vale in the

dawn sunshine…icy winter…thrusting Lake District storms…that MP who was on TV

all the time got killed in a car crash, skidding on the ice…everybody around me

already turning into ghosts…tell Sid…the Big Bang…pop music…love’s easy tears…oh,

well played, doctor!...Autoglass…cricket pavilions…because it is your own

heartbeat and stop ignoring it…”

Jermaine and Jaki

Ying and yang. Jermaine wants to know why they can’t just

dance and drink cherry wine (has anybody

drunk cherry wine?) and, you know, don’t cut to the chase when it’s the journey

that provides all the fun. This he does to a breezy, Whitney-esque backing

track masterminded by Narada Michael Walden. But Jaki just wants to GET with

it, oh come on, I’m YOURS, what are you WAITING for? It’s like Brian Hyland

colliding with Patti Smith at the Eric Dolphy Memorial Barbecue.

Control

“She looks like Michael, she sounds like Michael, she dances

like Michael…” So said whatever doughnut introduced the video for “What Have

You Done For Me Lately?” on TOTP –

perhaps it’s just as well I don’t really remember which DJ it was.

But that might have been Joseph Jackson’s original plan. Control was actually Janet’s third solo

album, but she had done her stint in Fame

and put out, or been persuaded to put out, two entirely nondescript albums; if

you don’t remember 1983’s Janet Jackson

or 1984’s Dream Street, then that’s

not amnesia; that’s memory doing its job. But Janet turned round and said

enough. She married James DeBarge in 1984, possibly to prove a point to her

family, but the marriage foundered less than a year later. The latter was the

subject of “What Have You Done For Me Lately?” but the song can be interpreted

as a wider kiss-off.

The album version – sadly we only get the 7-inch edit here –

begins with some pre-Beatles girl chat (“He does a lot of nice things for me…I

know he used to do nice stuff for you…but

what has he done for you lately?”). Then the song proper begins, although it’s

really a skeleton or a suggestion of a song; as with Prince, Jam and Lewis (to

whom Janet had been introduced by A&M’s A&R manager John McClain, whom

she had appointed as manager to replace her father) favour open-plan

minimalism. All the song’s elements flow through like paradigms; the Chiffons

harmony vocals, the tinkling at an abandoned piano – Janet’s voice is relied

upon to carry the song almost entirely. The song briefly opens up for its

middle-eight before slamming down the shutters again, words now more whispered

than heard, more spoken than sung (“Soap opera says, you’ve got one life to

live/So who’s right? Who’s WRONG?”). The song terminates as though run out of

bandwidth, and there’s some giggling and studio chat (“This is wild, I swear!”)

to close.

Control was 1986’s

Dare to Parade’s Penthouse And

Pavement (though both owed loads to Nightclubbing)

and is a pretty unimpeachable pop record. “Nasty” was the most significant

advance of what used to be called electro since Art of Noise’s “Beat Box” and a

titanic fuck-you-leering-misogynists yell of existence (and so the closing “Funny

How Time Flies (When You’re Having Fun)” is the record’s “Moments In Love”). Otherwise

the title track made “True Blue” seem like the less inspiring contents of David

Cameron’s Filofax, “You Can Be Mine” has a moment of silence and breathing in

its centre which might be the most sensuous moment in all of pop, “When I Think

Of You” drags Archie Bell and the Drells into the joyful noises of the

mid-eighties present tense, “Let’s Wait Awhile” – with “Lately,” the album’s

biggest UK hit single – was a more sinister, if silkier, variant on “We Don’t

Have To Take Our Clothes Off,” and even the Monte Moir-masterminded “The

Pleasure Principle” was superb. Many soul snobs were aghast that mid-eighties

black pop was referencing Gary Numan album titles (and approaches), but then I

often think that soul snobs get aghast at recognisable melodies or hooks, or

the present tense, or electricity, or the wheel.

From Numan To Human

Crash isn’t a

totally unsalvageable record, but it feels as much a product of unwanted duress

as Dream Street; by 1985 Jo Callis

had left the Human League and Virgin, worried that the group weren’t coming up

with anything new or usable, suggested that they fly to Minneapolis to work

with Jam and Lewis, who in turn viewed the group as a possible bridge for them

to the pop mainstream.

So they did, but the two sides didn’t get on; Jam and Lewis

regarded, with growing horror, the group as idle slackers, treated two of its

members as though they were infectious diseases (one left immediately after the

group’s return to Britain, the other the following year) and made them do what

it said on Jam and Lewis’ tin. Whether “Human” was an Alexander O’Neal reject

isn’t clear – but, as written and produced by Jam and Lewis and performed by

the Human League, it was one of the greatest records made by either.

And “Human” largely works – and took the group back to

number one in the USA as a result (and number eight in an ungrateful, entitled

Britain) – because it’s the Human League

performing it, as though having emerged from the dense fogs of “Louise” and “Life

On Your Own.” Thus Phil Oakey can sing “Born to make mistakes” or boom “Won’t

you please forgive me?” and you can immediately identify with him. It’s Joanne,

rather than Susanne, who does the mid-song talkover, where she confesses to

having been “human too” and cheated while they were apart. But her Sheffield

Co-Op fish counter “Aye-for-GIVE-YEOUUU!” won doubters around instantly. It is

as if they’re in the pub or the chippie, singing SOS Band songs to and for themselves.

Another Annoying

Boris

Boris Gardiner was there

virtually from the birth of reggae, as original bassist with the Upsetters and

producer of various post-ska favourites, one of which, "Elizabethan

Reggae," hit big in 1970; but by 1986 he had long since mellowed into a straight-down-the-line

MoR crooner, a sort of JA Johnny Mathis. The fact that "I Want To Wake Up

With You" was subsequently covered by Engelbert Humperdinck should confirm

its very tenuous connection to Lovers' Rock, even though it is strictly

speaking Britain's biggest-selling Lovers' Rock single, and in the

post-"Under Mi Sleng Teng" reggae world it came across as even more

old-fashioned. But it crossed over to the punters who thought that Dennis Brown

wrote The Singing Detective, and its

simple and rather repetitive construction was enough to make it 1986's big

last-dance/first-wedding-dance smoocher. Gardiner sings it with fulsome

mellowness, but the sentiments are at times rather creepy ("I want you to

be/The first thing that I see" – what is this, Nick Cave?), but in the end

it's the type of pop reggae which makes late-period UB40 sound like Red-periodBlack Uhuru. Entirely

unexciting, as per its ghastly AoR synth intro, and it knows no more than to

repeat itself until the studio clock indicates that the three minutes are up,

whereupon it fades into the universe, in some distant pocket of which the song

is presumably still playing.

So

There’s not too much more to say about “Don’t Give Up” that

I haven’t already said, but I note its position at the head of a rather

meaningful side three. We’ve seen what the surface of Thatcher’s Britain can

look like, but now we are made to realise its unwelcome underbelly, the need to

tell the story of the people who didn’t fit into the pattern, or fell through

its many holes. And still, here, despairing and on the precipice of suicide,

Gabriel is repeatedly told, in increasing, “Imagine”-like detail, that he is

not alone, that if he is to survive he can only do so as part of an integrated

and harmonious community. The people have to live; so must he.

Think About The

Housemartins

Because this is what happens when community is denied, or

dissipates; Thatcherism has happened, and Paul Heaton walks down the streets he

has known all his life, but nobody stops or speaks or cares any more. “And now

it’s almost here, now it’s on its way” he sings quietly, as though expecting

nuclear holocaust in five seconds, “I can’t help saying ‘told you so’ and ‘have

a nice final day’.” The harmonies are as stalwart as the Seekers or the

Spinners (the Liverpool ones) but the change that has come is cold and

merciless. “Now apathy is happy that it won without a fight,” intones Heaton

two hours ago. The group rise to a fearsome crescendo underneath Guy Barker’s

outraged, slurred, muted trumpet before dying down again. The song is a plea to

stop, to think, to live again.

Utter Madness

Well, I have to be precise here: the Pet Shop Boys sang “You

can’t hide,” but Madness warn “Don’t try to hide.” Their final single (in their

original incarnation), appeared on the Utter

Madness compilation (which only reached #29) and Mike Barson was briefly

back (though absent from the video). “Ghost Train,” a Suggs song, demonstrated

that the gloom of Mad Not Mad had in

part not dissipated (“Waiting for the train that never comes”), but it was

another anti-apartheid protest (“It’s black and white!”) with the warning that

change WAS going to come whether people were ready for it or not. So they

depart – for now – with some hope.

Hello Again?

Who would have expected Status Quo’s biggest hit of the

eighties to be a synthesiser-dominated anti-war ballad written by a pair of

South African brothers? But that’s what “In The Army Now” was; a lament of

increasing lyrical and musical intensity – when guitars and drumkit erupt in

the final verse, the impact is unsettling. He’s going to be a hero, but he

never told you he wasn’t coming back. He goes, and gets trained to fight, and

it’s not Noddy Holder yelling “STAND UP AND FIGHT!” halfway through. The whole

record was a brave gamble that paid off, and it is only a pity that the

fundamentally conservative Quo toned down the lyric considerably when they

re-recorded it as a Help for Heroes fundraising record in 2010.

It’s A Non-Mover, He’s Stuck At Number Nine, He’s Stuck On You, He’s Huey Lewis………….AND THE NEWS!

It’s A Non-Mover, He’s Stuck At Number Nine, He’s Stuck On You, He’s Huey Lewis………….AND THE NEWS!

Well, it was “Stuck With

You” and in Britain it didn’t get past Number Twelve, but there’s more than a

touch of Gilbert O’Sullivan (imagine Gilbert covering, or rewriting, “True Blue”)

about Huey and his fellow San Franciscan updated yacht-rockers. He seems happy

enough with his Other, but the “stuck” is what sticks, as well as other

indications that he’s not quite as happy as he sounds; “We thought about

someone else, but neither one took the bait” (so the song is anti-“Human” by

obviating the need to sing “Human” in the first place) and the more sinister,

twice-repeated “We thought about breaking up, but now we know it’s much too

late.” “If we change our minds,” the singer observes, “Eventually, it’s back to

you and me.” Given that the song’s parent album Fore! also features songs like “Hip To Be Square,” it may well be

that this is just a reflection of Huey the born again home lovin’ man. But you’re

never quite sure.

One Great Big Country

“You

don’t see the possible pitfalls when you’re thirty. When you get into your

fifties and sixties, you see nothing else.”

(Brian

Clough, Cloughie: Walking On Water – My Life,

revised edition. Headline Book Publishing, 2004; p 150, Chapter 12: “Twenty

Years Ahead Of Our Time”)

The

train pulled over the bridge, over the Clyde, into Central Station two Saturday

afternoons ago. There was no border patrol, no passport checks. I wasn’t quite

sure what we were travelling into. But I do know that when we emerged from the

station into Union Street, it didn’t seem anything other than an average late

summer Saturday afternoon in Glasgow. I understand there had been something of

a to-do in George Square on Friday evening, the roots of which are far, far

older than Glasgow itself. But here, everything was calm. Or so we thought. Isn’t

it nice, we thought as we crossed Gordon Street on our way to the bus stop, how

cyclists actually stop and wait patiently at traffic lights? But no; once back

onto Renfield Street., there were two parallel idiot Bradley Wiggins wannabes,

racing at length and downhill along road and pavement. Good Lord, I thought to

myself; is everywhere going to end up

like London?

“Self-belief

exacts a price. For those who have never felt the loss, reality comes in hard

and collects, especially when it is fenced around with the choices of the

timid, the fearful and the willingly deceived.”

(Ian Bell, “Dear young Scotland, thank you for daring to believe…,” Sunday Herald, 21 September 2014, p 13)

(Ian Bell, “Dear young Scotland, thank you for daring to believe…,” Sunday Herald, 21 September 2014, p 13)

We

didn’t spend much time in Glasgow itself during our week up there. The reason for

this is that we had our hands full looking after my eighty-one-year-old mother,

who has recently undergone cataract surgery; making sure she got her eye drops,

keeping the place clean (and cleaning the place up), aiding with shopping, helping

out with (and sometimes fully cooking) meals, and so forth. We had one day out,

and again it did not seem that anything, untoward or otherwise, had happened.

Record

shopping in Glasgow is different in kind but not too dissimilar in nature from

the model I had known in my youth. Right next to Queen Street station, there’s

Love Music! records, a very decent new and used shop with a young chap

energetically playing an Elvis pinball machine (it was also the only shop I’ve

seen which actually stocks the Common

Linnets album). Come out again and you can go straight down the subway and take

an eight-minute, four-stop Underground train journey to Hillhead, where all

homesick Londoners venture – it even has its own Waitrose. Back on the

Underground to St Enoch and you have a surprisingly good HMV which is a sight

more negotiable than the one next to Bond Street tube. Keep going up to

Trongate, turn down King Street and you find Monorail, although the actual

record shop component was hard to find and involved walking through the middle

of a restaurant/coffee bar. Like Love Music!, Monorail specialises in the chloride derivative method of musical reproduction,

but since I live in the twenty-first century and don’t bother even looking at

records, as such, any more, I go by the CD racks – again, if I were sixteen again, I’d

think this the greatest place ever, but on further exploration we found nothing

that we actually wanted to buy (new releases were mostly out of the Hillhead

Fopp) and it made me crave for, of all places, Rough Trade East, where the

coffee n’ munchies bit at the front doesn’t obscure the far wider range of

music stocked behind it.

Maybe

I’m spoiled, because, as everybody allegedly knows, Glasgow – and I stress

Glasgow here rather than Scotland – is about people above everything and

everybody else. As a city it’s far better constructed and transport-friendly

than London. Even when you’re on a packed bus, everybody looks out for everyone

else and if somebody coughs or trips over on something, there are condolences,

comfort and fulsome apologies, as opposed to London buses, where doing similar

is liable to land you in serious, resentful trouble.

So it’s

the old story – Glasgow, nice to visit, but when you’re there you just think

about getting back home again, and then once you are back home, you suddenly start to miss it.

However,

it’s not just, or at all, about me and my dopey pasted-on nostalgia.

“…And

talk of much of nothing while the shouting still goes on,

But

we are only singers until better songs are sung.”

Oh,

shut up, Carlin, you didn’t have a vote, you left, the choice was yours, you’ve

forfeited the right to complain or comment. It is a very fair point, that. But,

like the Yardbirds, still I’m sad. Sad that just over half the people of

Scotland looked the future in the eye and finally said “no.” Now I’m not going

to have a go at these people; they had reasons which they believed were valid,

they thought about it. And many of these people were, finally, afraid.

I do

believe they should be more afraid of what they have (re)signed up to, that

Gordon Brown came through at the eleventh hour and is already reduced to

calling for a petition. They believed the snake oil salesmen and their promises

– which now can be safely buried or set aside; don’t you people realise there’s

a war on? – and that, finally, was their decision, their call.

But that

has to be balanced by the fact that just under half the people of Scotland –

the considerably younger half, by and large – said “yes.” This was no

landslide. And yet, watching the news bulletins in the succeeding days, it was

hard to escape the notion that, actually, this little demonstration of

community was very touching, but can we just sweep it under the carpet now and

get back to normal? There was talk of taking the renewed fervour back to

Westminster, but you knew and I knew that that was never going to happen;

looking at Milliband delivering his clichés, Scottish Labour types acting like

corporate robots and avoiding answering any tricky questions, or Shapps warning

Tories thinking of defecting that they might get six of the best in his study –

if this busted 400-year-old flush is all you have to offer the people of now,

you can hardly whine if you get 20%, or worse, turnouts at elections. Not when

you are being asked to pick which supermarket chain is better – Aldi, Lidl or Tesco.

“I’ve

seen the way of prophets and I’ve seen the way of kings

I’ve

seen the hope that love can bring.”

Because

what the whole independence referendum affair has proved, it is that if people

are faced with something on which they have to take a stand, one way or the

other, they will turn out. They will team up, they will work together, they

will get communities going. Give them something to believe in and they will act

on it. Give them three hardly-differing variations on the same austerity riff

and they’ll go back to sleep, or worse.

Because

the one-size-fits-all model of Westminster government, with its tired palace

court/public school/high table rituals, has been shown to be outdated,

ineffective, inadequate and unfit for purpose. I do believe that, taking

Scotland as a paradigm, other parts of the country should express thought-out

arguments for more local governance of their affairs, with the Commons needing

to do no more than keep a careful but non-interfering hand on the till.

Or

maybe it’s already too late for that. There is also the feeling that

governments do not really govern nations any more, that the world is now run by

multinationals who care only for the money to be raised from passive

consumerism, and servicing of same. The dreadful prospect that a few years

hence, democracy may be viewed as an interesting but failed experiment, as

everything otherwise appears to be hurtling back towards a technology-enhanced

Middle Ages. If I’m really honest, I expect humanity to have wiped itself out,

messily and painfully, well within my lifespan.

Why?

Because if the human race can be viewed as a single human being, it must be

observed that over several million years it has barely evolved to nursery/kindergarten

level. It is still too obsessed with putting itself first, biting the bars of

its playpen and, above all, clinging to the shiny toys which will probably end

up destroying it, from which it cannot wean itself off, like the cat with the

ball of string. The difference is, when it happens, it will probably take

everything and everybody else along with it.

“I

only hope what pleases me will also pleasure you

For

might can never be the hands that make a dream come true.”

“If

might is right, then love has no place in the world, it may be so, it may be so.

But I don’t have the strength to live in a world like that, Rodrigo.”

(Jeremy

Irons’ Father Gabriel to Robert de Niro’s Rodrigo Mendoza, from the motion

picture The Mission: 1986)

I don’t

know that I do, either. And in the end it may not be up to me. London I can now

view as being bearable – just. But if

the time comes – and it really may not be that far off – when nobody will be

able to afford to live in London except celebrities, financial workers and

trustafarians, then I will have to look elsewhere. But it is a Britain-wide

problem, a country where food banks are increasingly being regarded as normal

and routine, where those who have the misfortune to fall ill or otherwise not

fit in with the plan are deemed not worthy of help or compassion but left in

the gutter – some other city or town’s gutter, at that – to rot, and whose

obscenely rich cannot be compelled to pay more taxes because the country’s

manufacturing system has supposedly been so asset-stripped that nothing is left

for us to offer except financial services and tourism. To be the rest of the internationally

rich world’s butler.

The whole world as The Village.

A Britain which, in every aspect - war anniversaries, the umbilical attachment to long-playing records and banjos; I could go on, but won't - will end up driving right off the motorway because it couldn't take its eyes off the rear-view mirror (to paraphrase Todd Levin).

I don’t know what more I can offer. One of the least frequently-discussed reasons behind these last thirteen years of online music writing is the hope that enough people might find my writing good enough to offer me more, paid, work such that I might get enough of a reputation to make a living out of doing it, might have something to see me through the second half of my life. Yes, I look at where I could afford to live in Glasgow and it’s infinitely more affordable than London. But I also have to remember that I am almost fifty-one years old, that I had a minor stroke almost three years ago which means there’s a limit to what I can do, and that therefore I do not represent the most promising employment prospect to those who don’t know me. Whereas I currently work in a place where everybody knows and likes me and what I do, in a part of town that I would know blindfolded. And I have been in London for nearly three decades and can’t as though the time, or the place, never existed.

I don’t know what more I can offer. One of the least frequently-discussed reasons behind these last thirteen years of online music writing is the hope that enough people might find my writing good enough to offer me more, paid, work such that I might get enough of a reputation to make a living out of doing it, might have something to see me through the second half of my life. Yes, I look at where I could afford to live in Glasgow and it’s infinitely more affordable than London. But I also have to remember that I am almost fifty-one years old, that I had a minor stroke almost three years ago which means there’s a limit to what I can do, and that therefore I do not represent the most promising employment prospect to those who don’t know me. Whereas I currently work in a place where everybody knows and likes me and what I do, in a part of town that I would know blindfolded. And I have been in London for nearly three decades and can’t as though the time, or the place, never existed.

So

the conundrum is there. But enough self-pity and back to Scotland, and

self-determination. What can be said, other that this won’t be the last time

the question will raise itself, that for a huge proportion of people the old

games won’t work anymore, that there can be no going back, but that there is

still the chance of creating a new society, free from fear and ruinous

self-interest, of which I would feel fully comfortable and happy, even at my

advanced time of life, to be a part.

And

Stuart, you stupid, glorious eejit, you should have fought, taken your own

advice and stayed alive, just to see what is happening and what is still

changing.

Billy Bragg

“The

Difficult Third Album”, Bragg called Talking

With The Taxman About Poetry, but it is probably his best, while still

leaving the slightly sinking feeling that I had about it at the time: was this,

or Bragg, really the best the other side could do? I doubt that the New Labour

which eventually came into existence would have had any time for a poet

(Mayakovsky) who proclaimed himself a “Communist Futurist” (he was in at the

birth of the original art of noise back in 1912; “With my heart’s bloody

tatters I’ll mock again/Impudent and caustic, I’ll jeer to superfluity”) and,

although there are more musical and production trimmings here than on its two

meat-and-potatoes predecessors, I’m not sure that Bragg emerges from his

self-constructed trap – the Dylan variation of “Ideology” is moderately

intriguing and it’s nice to know that somebody else remembers what a great band

the Count Bishops were (“Train Train”) but the far too referential and reverent

“Levi Stubbs’ Tears” is uncomfortably close to Nick Hornby or Rob Fleming’s

idea of a pop song (despite its great central four-chord guitar riff; in 1986

Levi Stubbs was the voice of Audrey II in the Little Shop Of Horrors remake!) while things like the cover of

“There Is Power In A Union” and “Help Save The Youth Of America” are akin to

being lectured to (wrongheadedly) rather than being entertained.

Bragg

is generally better on the mechanics of personal relationships, and although

“Brunette” does not quite escape the written-by-slogan quandary (“Politics and

pregnancy/Are debated as we empty our glasses”) it’s a reasonable

stage-by-stage analysis of a relationship gradually running into trouble (it’s

the Specials’ “Too Much, Too Young” as viewed from the inside) wherein Bragg

steadily and systematically deflates love song tropes to find messiness and

disharmony. I am not sure that what he proposes should replace them are in

themselves any better. But the unmistakable contributions of Johnny Marr and

Kirsty MacColl make it listenable, and in Bragg’s octave-attempting jumps of

“Shir-LEE-EEE!” one visualises a nineteen-year-old Noel Gallagher, carefully

listening and learning the ropes.

Cutting Crew

Had I

been compiling this record, and the artists in question had been agreeable to

licensing it, and given the involvement of Marr, MacColl and co-producer John

Porter in “Brunette,” I would have ended this side with the Smiths’ “Ask.”

Instead it ends rather unsatisfactorily with this moderately misogynist piece

of AoR written and sung by (in the video) a very smug-looking fellow. Actually

Cutting Crew were Anglo-Canadian; frontman Nick van Eede had been leading a

band called The Drivers, who hit in Canada in 1982 with “Tears On Your Anorak”

and were touring the country when they ran into the late guitarist Kevin

MacMichael (born in Saint John, New Brunswick, but brought up in Dartmouth,

Nova Scotia) who at the time was in a Halifax-based band called Fast Forward.

They teamed up, returned to Britain and formed Cutting Crew in 1985.

I

can’t stand “Died.” The protagonist has sex and is now feeling hugely guilty

about it – and of course the woman (be it a prostitute or former lover or

one-night stand) is fully to blame (“She’s loving by proxy, all give and no

take,” “On the surface I’m a name on a list,” “I followed my hands, not my

head/I know I was wrong”). Given the don’t-do-cocaine lecture that was their

subsequent “Mirror And A Blade,” this, and they, could be dismissed as

self-righteous bores. When “Died” topped the Billboard chart in 1987, there were rumours of payola. Here they

just needed the boneheads of Radio 1.

Kim Wilde

Was

it really true that Kim was B.E.F.’s first choice for singing their Music Of Quality And Distinction version

of the song, before passing it on to the late Bernie Nolan? I’m not sure about

that, but when Kim and brother Ricky came to rework it four years later they

far outdid the Sheffield lads in impact and intensity. It is said that the

Wildes actually weren’t too familiar with the Supremes’ original at the time –

thus some of the minor changes in both harmony and lyrics – but compared with

Vanilla Fudge’s leaden ninety-eight-minute crawl through the number, they did a

great job of actually covering a song as though it were new. Kim joined the

Human League in the New Pop “Look who’s back on Top Of The Pops/back at number one in the USA again!” stakes and

sings the song with real fire and I suspect not a little resentment at The

Industry (“You keep USING ME!”). One of her angriest and best records.

It Bites

In

case you cared, it was the tagline from a television commercial for Kestrel

lager, and the band came from Egremont in Cumbria – the first Cumbrian act to

make the top ten. But “Calling All The Heroes” is atrocious, as was their

unison jerking bodies and heads/punk never happened routine on TOTP. It was exactly the kind of unsatisfactory

rubbish that the now serially-discredited Radio 1 insisted on force-feeding its

listeners in the retrospective hope that punk might not have happened.

Prog-pomp in all but surface, and Francis Dunnery’s awful sub-Elvis Costello

vocal, with a lyric about city bandits and mountain saviours which could be

interpreted as righteous Thatcherites seeing off those awful Lefties (remember

all those print disputes of 1986? This could pass as their soundtrack),

complete with 1979 fake-new wave “Shooting up the tow-en, bo-ieezz” refrains.

Bullingdon pop.

Waterloo

Sometimes

the compiler got it wrong. From the notes to this on the album’s sleeve, you

get the assumption that people thought this was going to be a Christmas number

one. How could it fail – Doctor and the Medics had already had a number one

earlier in the year, and Roy Wood himself was on hand to help out, in part

recompense for “Waterloo” being inspired by Wizzard in the first place. All

well and good - if, that is, you ignore the Doctor and the Medics part – but

the record was a ghastly mistake; almost immediately we are back in the world

of the Top Of The Pops soundalike albums – to be precise, side two, track

one, of Volume 38 (whose sleevenote begins: “Well Kids, Teenagers, Wombles,

Mums and Dads, we’ve cracked it – we hope” – alternatively, the sleevenot

writer could be cracking up) – with a dull, sludgy reading of the song that has

had all its pop, fun and sensuality drained out of it. Wood turns up at the end

to parp some half-hearted-sounding saxophone when really he should have been

given the whole record to redo. As things turned out, this record peaked

forty-four places lower than the Abba original.

Debbie Harry

Blondie

ended their career penniless because of a naughty manager, Chris Stein was

seriously ill and his medical bills needed paying – so Rockbird was never anything more than a quick and easy money-making

exercise. I don’t think Debbie Harry enjoyed recording it and certainly on the

cliché-drenched “French Kissin’” there is the feeling that she has been

pressganged into doing this song. Ex-J Geils man Seth Justman produced, but

there is little of the old Blondie sparkle. Curiously the “C Lorre” who wrote this

half-arsed apology for a song turns out to have been Chuck Lorre, who went on

to devise sitcoms such as Dharma And Greg,

Two And A Half Men and The Big Bang Theory; like Modern

Romance’s Geoff Deane, I expect he was far happier with one career than the

other.

Addicted To…?

The

third Jam and Lewis song on this collection, and originally recorded by

Cherrelle. Far more propulsive, purposeful and enigmatic than “Addicted To

Love,” it also leaves open the question of how different a pop song sounds

depending on the gender of the person singing it. In Cherrelle’s hands it was a

more tactfully diplomatic variant of “Nasty” – he wants more after a night out,

she doesn’t, and she sounds decidedly uneasy about it (it really isn’t that far

from “The Boiler”). Whereas Palmer performs the song as though from behind his

cufflinks, with the same numb terror we recognise from “Billie Jean.”

Unnerving, not least because its video and that for “Addicted To Love” were

identical.

Top

Of The Pops

It

was the new theme tune. If only Now

had existed in 1982 and Phonogram had agreed to license “Yellow Pearl.” It’s an

entertaining enough quasi-instrumental electro-romp sampling Vincent’s cackle from

“Thriller” which ends with a gnarled old voice (possibly Hardcastle himself)

snarling: “I command thee to buy this rotating plastic demon, or I will curse

thee to the end of time!” He has subsequently become very successful in the US

jazz-fusion/smooth jazz field.

Gwen Guthrie

Should

have been “Ain’t Nothin’ Goin’ On But The Rent” – along with “Love Can’t Turn

Around” and several otherwise unaccountably absent others, it can be found on

the Now Dance ’86 collection of

twelve-inch mixes (the apparent nature of that song’s lyric certainly rubbed me

up the wrong way at the time in a “if-you’re-unemployed-you-are-untermensch” way, but actually it’s the

very opposite, the cry of the desperate – “BILL COLLECTORS AT MY DOOR! WHAT CAN

YOU DO FOR ME?”) – but instead it’s a forgettable open-the-freezer-door stroll

through the old Carpenters standard. I don’t think that either Bacharach or

David had the expression “sexy, ooh, ooh” in mind when they wrote the song.

Wicksy Endgame

From

the very first shot of episode one, when the door is smashed open to reveal the

decaying figure of a dead old man in a rotting armchair, the BBC's premier soap

opera EastEnders was never going to

be a harbour of sunshine and light, and over its subsequent twenty-nine years –

it’s been in London as long as I have - it has kept that promise. None of its

thousands of hapless characters has been allowed more than a glimpse of what

might be termed happiness or hope; always the chance is snatched or pushed

away, misery invariably embraced over love. The series has tended to take its

original remit to be "the anti-Coronation

Street" rather too literally, and yet it has continued to attract

millions whose only derivable pleasure from the series can be their own

knowledge that however wretched their own lives might become, nothing could

conceivably be as disastrously terminal as the car crashes witnessed nightly

with the peeling puce house sets, the lighting which invariably looks as though

somebody forgot to put a shilling in the electricity meter, even when out in

the Square of Albert in midsummer. Lapsed lovers - usually men old enough to be

their lovers' father, and women young enough to be their lovers' daughter - are

re-courted in grimy gents' toilets within the Underground station. Familial

tensions in the local pub can resemble the last days in the Berlin bunker.

Though a supposed suburb of the East End of London, "London" remains

a quotidian chimera, rarely glimpsed, mentioned only in passing ("I'm

goin' up West!"), and indeed the whole thing is filmed out in Borehamwood;

at times it looks like one of those stranger, later episodes of The Prisoner where McGoohan wakes up to

find himself in a mock chirpy Cockney community.

The

series, however, was spectacularly successful in its first year, such that the

BBC opted to launch some external brand awareness by having some of its cast

"sing." Thus Anita Dobson, the tormented barmaid Angie Watts (a.k.a.

Mrs Brian May), made number four with her vocal version of the show's theme

tune, "Anyone Can Fall In Love," while Letitia Dean and Paul J

Medford (Sharon Watts and Kelvin Carpenter, the show's primary "teen"

interest) also went Top 20 with their offensively bland "Somethin' Outta

Nothin'," allegedly performed by their pop group, The Banned (geddit?).

The

most successful spinoff by far, however, was "Every Loser Wins" and

its story is thus. Teenager Michelle Fowler has foolishly fallen pregnant by

evil Machiavellian pub owner Dennis "Dirty Den" Watts - a man old

enough to be his lover's father - and in a curious melange of desperation and

defiance decides to marry the affable, amiable, borderline Aspergic barman

Lofty Holloway. But when the ceremony comes around (with her already having

given birth) she realises her heart isn't in it and jilts the hapless Lofty,

who thereupon crumples into a Kleenex of suicidal ideations. In pity, Michelle

reconsiders, and they elope to marry. However, after a couple of months of

Lofty's well-meaning but unsexy "Would you like me to take Vicky round der

park, 'Chell?" (for the now-born child is called Vicky, named after the

Queen Victoria pub - do you see what luminous avenues of plot we are strolling

down here?) Michelle calls the whole thing off, tells Lofty that she was

pregnant with, but aborted, his child, and moves back in with her family (or

"fairm-ly"). Bereft and broken (having screamed and sobbed "I

hate you!" at Michelle several hundred times), Lofty's only consolation

now is his best mate, Simon "Wicksey" Wicks, who throughout all of

this time has been playing a dolorous ballad on the pub piano about how

"every loser wins, once the dream begins" (for said

"Wicksey" is also an aspiring songwriter - not that this is ever

alluded to again in the series after about January 1987; a Nick Berry album crept out, almost unnoticed, right at the end of

1986 and spent one week at #99). Something about it catches Lofty's heart, and

with its regretful hues of "we nearly made it" and troubled water

bridges of hope ("Shine down on me/And those who believe/That we can make

it"), he wanders manfully out of Albert Square, out of the series and into

a still-successful radio sports commentary career.

The

ballad caught on with the public, too, and "Every Loser Wins" -

helpfully described on its front cover as "The song featured by 'Wicksey'

in EastEnders" - became the

year's big weepie, shooting to number one and outselling every other single

that year bar the Communards. It's as hard now as it was then to make anything

out of it; though skilfully hacked into shape by veteran soap song composer

Simon May, its over-facile construction, coupled with Berry's lugubrious and

unsteady voice (as a singer, he's a fine actor) and the bargain basement synths

and drum machines, place it in an odd limbo, stranded somewhere between a bad

British attempt at American AoR (Richard Marx, say) and a precursor of the

pained piano-based ballads in which Gary Barlow would specialise a decade

hence. And despite its belief that "we can make it," the song has

never, to my knowledge, made it onto CD; its 800,000 sold copies continue to

filter down through charity shops the land over, as demonstrated by the mention

of "two copies of 'Every Loser Wins'" on Saint Etienne's

"Teenage Winter"; a brief, novel attraction whose resonance was quickly

found to be hollow.

As

hollow as an adversarial party political system whose leaders care nothing for

their heartlands and everything for the same 10% of floating voters, even as

they systematically dismember the middle class system which forms the bedrock

of that same 10%.

As

hollow as the urge to make anything of oneself in any field now, creative or

otherwise, because publishers are interested in shiny Z-list celebrity trifles

rather than literature, or music retrospectives with plenty of pictures that

tell you nothing you didn’t already know or agree with, or anything that isn’t

provocative – and therefore doesn’t get advertiser-friendly hits – doesn’t get

published, or because you had the misfortune to be born to the wrong parents,

or attended the wrong school, or made the wrong friends at university.

As

hollow as a government whose interpretation of the marshmallow test is to come

back randomly and take the marshmallow away whether you intended to ear it or

not, in order to keep you competitive.

“Every

loser wins.” What a world it would be if that were remotely true, as opposed to

the barren planet depicted on the cover of Now

8 which this planet may soon resemble.