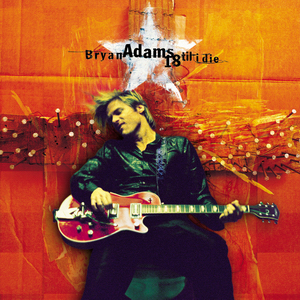

(#551: 22 June 1996, 1 week)

Track listing: The Only Thing That Looks Good On Me Is You/Do to You/Let’s Make a Night to Remember/18 til I Die/Star/(I Wanna Be) Your Underwear/We’re Gonna Win/I Think About You/I’ll Always Be Right There/It Ain’t A Party…If You Can’t Come ‘Round/Black Pearl/You’re Still Beautiful To Me/Have You Ever Really Loved A Woman?

It was a Wednesday. I remember that much. To be more specific, it was the morning of Wednesday the eleventh of August, 1971. It was a gloriously hot and blue day, just under a fortnight before I had to return to school for the new term. I was seven years old. My father was at work, so my mother took me out to a park which was not the one which we regularly visited in Uddingston (because I remember going out with my mother on the bus to Tollcross Park on many occasions), which was Maryville Park, adjacent to the Tunnock’s factory and close to what at the time was called Muiredge Primary School. On this occasion we went to a park, or a play area I guess you’d more accurately call it, on Kylepark Drive, where all the well-off people whose children went to school with me and barely tolerated me lived.

I can’t remember why my mother took me out there except maybe she fancied a change. But it was a very fine and relaxed morning. I took it upon myself to sing all the songs in that week’s top thirty singles chart – because at the time if you listened to the charts on the radio they only went down as far as number thirty – and link them in the manner of a radio disc jockey.

It just felt like the right and most natural thing for me to do in that setting and at that time in my life, and I must have been pretty good at it because before long my performance drew a small crowd of admiring girls and in some instances their beaming parents. I wasn’t there to make a racket or cause a fuss, but just to entertain as best I could.

Everybody who was there agreed that I was quite remarkable. I sang all the songs from that week’s top thirty, which had only been announced on the radio less than twenty-four hours previously, in sequence of ascending order and from memory. Some even started to sing along with me as the ninety or so sunny minutes went along. No fuss or unpleasantness; just communal happiness.

Looking at that top thirty, as I am doing now while writing this because I can’t really remember it these days without looking it up on the internet, even though when I was younger all the charts were in my head and I never needed to look any of them up, it surprises me somewhat that I managed to pull that performance off. I know it was this chart and it was the eleventh of August because for whatever reason I remembered that “La-La Means I Love You” by the Delfonics was at number nineteen. I don’t know why that specific statistic has lodged itself in my head.

Today of course I recognise the record as Thom Bell at his exquisite best. I did not know of “People Make The World Go Round,” which Thom Bell did with the Stylistics at pretty much the same time, and indeed did not hear it at all for another twenty-eight years until I heard a cover version on the Innerzone Orchestra’s album Programmed and tried to find the Stylistics album which included the full six-and-a-half minute version (not the three minute-plus edit you got on compilations). I found that on a lonely and hot Tuesday afternoon, slowly walking back to somewhere (Oxford), in a crate in a record shop on Wandsworth High Street. It was Tuesday the seventeenth of August, just over twenty-eight years since my performance in the park, and of course I wondered what I had lost. The fact that it was a time that I was not really meant to see perhaps underlines the unutterable otherness of the whole experience.

However, getting back to looking at that top thirty, I really am puzzled as to how I managed to pull it off. There’s “Street Fighting Man” by the Rolling Stones – a song which didn’t get much, if any, play on daytime radio but still I knew it – and other political songs like “Bangla Desh” by George Harrison, “Soldier Blue” by Buffy Sainte-Marie and “Won’t Get Fooled Again” by the Who. Advanced stuff for my age. And there was tongue-twisting progressive rock in the form of “In My Own Time” by Family and the groovy “Devil’s Answer” by Atomic Rooster. Also a record called “Leap Up And Down” by Saint Cecilia which the radio had belatedly banned because at the time you weren’t allowed to sing the word “knickers” on the air but I had heard Noel Edmonds or somebody play it and it was catchy enough to stick. I sort of bleeped the offending word out, to much laughter.

I remember how most of those thirty songs went but not in meticulous, microscopic detail. I had no unassisted memory of “Watching The River Flow” by Bob Dylan and had to turn to volume two of his Greatest Hits to remind myself how it went – oh yeah, that one! Most of it, though, was happy random noise, whether it was “Heartbreak Hotel” (doing the rounds on reissue), “Monkey Spanner” or Slade’s “Get Down And Get With It” (I really enjoyed yelling that one out!). Even “Get It On” by T. Rex, which was right up there at number one, I simply treated as a wacky singalong, not knowing that it was rather near the lyrical knuckle (well, how are you supposed to know these things when you’re only seven, with your cream shorts and your Apollo 11 embroidered patch which came free when you sent off three used Super Mousse wrappers?).

Today I can rationalise why this odd assortment of songs constituted a “hit parade.” August 1971 represented a liminal period in pop, when the old (sixties) order had largely incrementally bowed out and nobody was yet quite sure what was going to succeed it (T Rex and Slade were as yet happening in isolation). Back then all I knew was that pop records either made you feel sad (“I’m Still Waiting”) or happy (“Move On Up”) or indeed occasionally both (“Just My Imagination”). A lot of the time I still think that’s all you need to know about pop.

So why am I thinking about all of this nearly fifty-three years to the day later? Because of the promise that could never be fulfilled, not least by myself. Everybody who was present in the park that Wednesday morning was sure I was going to become somebody really famous. One of them commented, “hey, this is the next Tony Blackburn!”

Maybe I’ve scrunched it all up in my imperfect memory and I was merely blurting out riffs and hooks and making a lot of noises to cover up for lyrical ignorance. That’s a major reason why minute analysis of lyrics is simply the wrong way to approach pop writing. Blue by Joni Mitchell had already been out for a couple of months but all I knew about her at the time was the song about the taxi where she laughs at the end and she wrote “Woodstock” and “Both Sides Now” but both were hits for others. I didn’t hear the album until one Sunday morning, about two o’clock, at a Christmas party in Morden in December 1988. It immediately penetrated my being and I bought my own copy from Tower Records on Kensington High Street one day later.

In 1971, however, all I was concerned about was, was it pop, was it happy noise, and does/do either/both work?

Perhaps that is still what concerns me. In 1971 I was seven and people loved what I knew and felt about pop music. After a while, though, you gradually find out that you’re not really allowed to do it any more. I didn’t become a disc jockey because that involved doing shifts on hospital radio for not very much money and as I understood things, once you managed to get employed by a radio station you had to earn a living playing music you basically hated.

Yes, you might justifiably argue at this stage, but you did not hate any of that 1971 chart stuff in 1971, did you? To which I can only reply, no I didn’t. Pop was all around you in a manner fundamentally different from how it’s all around you now. By “all around you” in 1971 I mean that pop was in the air, everybody breathed it, whether they liked its fumes or not. Whereas “all around you” in 2024 generally means what’s feeding into your headphones as you listen to the hot pop hits of today online – and no greater community is there to share it with you, not any more.

So yes, I’d say pop music in 2024 is as good as it’s ever been, and qualitatively in rude health – but how would you, or anybody, know? Furthermore – and this furtherance is very important – I know that it shouldn’t be me telling this to you.

Because knowing and singing the top forty in 2024, at the age of sixty, is drastically different from doing so in 1971, aged seven, and unquestionably a whole lot more sinister. It’s an indication that, no, you haven’t really grown up, have you – and people are exceptionally suspicious about people who don’t and/or won’t grow up.

I might have liked all pop music in 1971, but just a few years later the hormones kicked in, then punk, and both alter you irredeemably. You are obliged to take sides, learn (or learn to learn) that you do not like some pop music as much as you like other pop music. Meanwhile, playground chatter about the charts – who beat whom to number one, who got the highest new entry, where did THAT record come from, etc. – dwindles or mutates into talk about driving lessons, work placements and mortgages.

You are, in short, expected to grow up and put childish things away, including (implicitly and sometimes expressly) pop music. The other week I walked into the office humming “Good Luck, Babe” to myself – it’s catchy! – and you’ll never believe the blank stares I got in return, like, who is this ageing weirdo? You’re supposed to have “graduated” to classical or jazz or grown-up album artists, or to have stuck with the songs that were big when you were fifteen. Charli xcx or Billie Eilish don’t give a fuck if I think, never mind what I think about their work, and why should they – theirs isn’t intended to be “my” music, and quite rightly so; piss off back to the Beatles, grandad.

(Actually, as Ian Martin has commented elsewhere, it’s quite liberating to get past sixty and realise that you can think and say what you like because nobody truly gives a toss; it’s your deemed societal function to become a grumpy old git, because what are young people otherwise going to react against?)

So yes, like Max Schumacher in Network I am fully aware that things are far nearer to the end now than to the beginning. How is one expected to respond to that incrementally dire knowledge? I didn’t stop loving pop music because it is presumed to carry an expiry date. I listen to new music because I don’t want my mind to atrophy and consign me to a nursing home. I cannot live for, let alone in, the past. Orpheus loses Eurydice forever because he looks back. Lot’s wife looked back at burning Gomorrah and turned into a pillar of salt.

Hence you could say that it’s not exactly a great or helpful idea to look back, argues the co-author of a blog looking back. Maybe it’s down to how you do the looking, the angle of your gaze. But the reaction I’d get now if I attempted what I did at Kylepark over half a century ago would be horrible, brutal and probably terminal.

And of course I shouldn’t even think of attempting it. In the real world I of course wouldn’t. But there’s that irritating little subtext of a question, isn’t there – okay, you’ve been told to grow up, and you shouldn’t even be told, you should just do it, so no more swings and roundabouts in the park, and no more pop music. And then I’d have to go into a paraphrase of Limmy’s sketch about the swing, saying – all right, I’ll stop listening to pop, I’ll fit in. What have you got to replace pop music? I’ll tell you. NOTHING. Work, work and more work, which is all school trains you to do anyway, relieved only by booze, fags, maybe drugs, and inadequate holiday fortnights (provided you can afford any of these). No wonder people are fucked up, etc. etc.

So perhaps Kylepark in 1971 was my personal Millport. A moment which cannot, and should not, be recaptured. But, hey, this enduring, consumerism-based belief that you can go on being a rock ‘n’ roll adolescent forever – I can’t be seven until I die, let alone eighteen. Not even if I were born in a leap year.

Postscript

Yet all memory is fallible. Until quite recently I believed profoundly in the perfect day, which for me was teatime on Monday 15 August 1971. My parents and I were walking back from Bothwell Castle. The weather was beautiful. My father carried our transistor radio and we listened to Radio 4. Specifically I remember listening to Brothers In Law, a situation comedy about the world of barristers starring Richard Briers. I don’t recall anything specific about the show – least of all whether it was funny - but it felt good and fitting.

Being the age that I am now, however, I looked all of this up online yesterday. Not only was that Monday the sixteenth of August, not the fifteenth, but the evening repeat of Brothers In Law did not go out until Thursday – the nineteenth.

I note that track two on the abovementioned Innerzone Orchestra album is entitled “Manufactured Memories.” Track three is entitled "The Beginning Of The End.”