One question I sometimes get asked by correspondents is: why

not write a book on how to listen to music? I don’t know whether such a thing

is possible. There is a compilation of old writing for newspapers and music

magazines which impertinently calls itself Ways

Of Seeing but is anything but. Furthermore, there is a digest from the 33⅓

people optimistically or pompously subtitled How To Listen To Music.

Listening to music – as opposed to hearing it – is actually

one of the most difficult tasks there is, probably because only one of our five

senses, that of hearing, is required to engage in it. As Derek Bailey

rhetorically asked Ben Watson in the late nineties, what do people do when

they’re listening to a record (as opposed to watching a musician perform live,

with its own quantity of distractions, including ones which may involve all five

senses) – read a book? Make a cup of tea? In that case, all you have is

wallpaper.

Instructing, or guiding, people on how to listen to music is

also fraught with difficulties because music is not cinema or television, where

at least two senses are required, and that of vision is always the primary one.

Hence it is quite easy to write manuals like David Thomson’s How To Watch A Movie if you know your

stuff, since, as Thomson points out, the attentive film viewer has to spend

quite a lot of time looking at people looking at other people (this is also

true, to a lesser extent, with live theatre).

But how to indicate that when listening to music, you should

be listening to people listening to other people? It certainly isn’t

impossible. Jazz, for instance, is primarily constructed of people listening

and reacting to other people – and, if you’re a careful listener, so are such

musics as folk, devotional raga and gospel. But that is one of the reasons why

in the end I think jazz the best form of music, namely that it is a true

people’s music insofar as you are witnessing something being constructed from a

very basic foundation and put together in such a way that it becomes its own

ekphrasis. When you listen to a piece of improvised jazz music, you are listening

to people listening to each other. You are listening to a society forming

itself, to suggest a way in which humanity might better coexist.

There are other theories, of course.

Fear Of Music (Why People Get Rothko But Don’t Get Stockhausen) by

David Stubbs is a fascinating book which, when not serving as a whistle-stop

tour of/rough guide to subversive art and music throughout the twentieth

century, tries to find answers to the question of why people can generally

assimilate modern art but seem to have insurmountable difficulties with modern

music. Stubbs comes up with a number of possible explanations, including the

“Original” theory, the thrill engendered by owning something unique and

non-reproducible; but my kneejerk response to the question would be that, for

better or worse, humans respond far more quickly and readily to visual than

aural stimuli. It’s the way we’re programmed and extends into all areas of life.

Always it comes down to what somebody or something looks like. Furthermore,

painting, cinema and theatre demand sensory engagement – the visual focus is

far more overpowering than the aural one. We can’t walk away from a film – but

we can vacate the room if a piece of music annoys us. Even when it comes down

to the business of music “appreciation” the visuals are of primary importance;

look at your music collection and see how it is organised, how careful the

colours of the sleeves you chose, consciously or subconsciously. I myself have

not admitted several very worthwhile records into the house on the grounds of

their atrocious cover design.

None of this, however, gets us any closer to a notion of how

to listen to music (never mind “why listen to music?”). Perhaps we were better

off in the days when records came with a simple cover photograph or design,

track listing and (occasionally) credits. When we didn’t know – indeed, were

not expected to know – the history of a record or the person or people who

recorded it. One had to create one’s own mythology out of what one heard, find

one’s own interpretation. My CD copy of the “Limited Edition” of the first

Enigma album certainly carries little other than that – the

Play School Caspar David Friedrich of Johann

Zambrysk’s cover drawing, three distended quotes (one of which may have been

made up) and no credits whatsoever.

Therefore, if my intention were to make sense out of this

strange record, I would have little to go on apart from outside research. I

would have to trust my own ears and my own experience, and listen to the music.

But it’s easier said than done. So much of what surrounds the act of listening

to music succeeds in shrouding or otherwise obscuring the act. We come to a

piece of music with prejudices and preconceptions which we cannot unlearn or

untrain ourselves not to have.

A case in my point are the Eagles (yes, I know they are

strictly speaking called just “Eagles” but I suspect

nobody omits the indefinite article now). For decades I couldn’t

get them, having been endlessly bombarded by four or five of their songs on

oldies radio during those same decades, which do distort the full picture of

what the group had to offer. Hence it was with some surprise that I learned of

“Journey Of The Sorcerer.”

It appears at the end of the first side of the group’s 1975

album One Of These Nights, much of

which still sounds to me like a careful gallimaufry of half-decent songs and

ideas buried beneath an avalanche of green triangular Quality Street chocolates. “Sorcerer” was

composed by Bernie Leadon, who had joined the Eagles from the Flying Burrito

Brothers – he is the umbilical link between the two, and would angrily quit the

group before 1975 was out – and is a long and patient instrumental with three

clear peaks, none of which is exactly identical and all of which are reached by

different routes. Essentially a concerto for prepared banjo and string

ensemble, very much harking back at psychedelia, “Sorcerer” is a rueful wave of

farewell to any elements of country or bluegrass in the Eagles’ music, and its

coda, featuring the fiddles of David Bromberg, is testament to this box being

closed forever.

Whichever way the music reaches those peaks, however, the

peaks become immediately familiar once they come into view for they form

something very familiar indeed to people of a certain age – the music was used

as the theme to The Hitchhiker’s Guide To

The Galaxy and continues to strike me as the band’s most coherent and

affecting statement, perhaps doubly so when you consider that it bears no

words.

Indeed, listening to the steady build-up of notes, effects

and instruments, with Jim Ed Norman and the Royal Martian Orchestra sweeping

into sight like a grand, benign mountain range eroding doubt, sixties and

seventies finding a common cause and language, I don’t just wonder how well

this would have fitted into SMiLE,

but also think: isn’t this the Great

Cosmic American Music that Gram Parsons once promised in its fullest

realisation?

But Leadon left and was replaced by Joe Walsh, and the band

proceeded towards a bombastic rock dead-end (Hotel California is Steely Dan if they had stuck to watching The Beverly Hillbillies). Nevertheless,

this “Sorcerer” compelled me, even if only for a shade under seven minutes, to

reconfigure their art in my mind and to do so by listening.

To this end I have attempted to give MCMXC a.D. a fair hearing. In truth I would hitherto have

considered the record fortunate to have been given one paragraph of TPL. However, I was encouraged to give

complacency the body swerve by what Mark Sinker wrote about the record on Freaky Trigger. As with all music

writers worthy of the name, Mark made me think about the album anew, forced me

to come to terms with my own prejudices. Hence this piece.

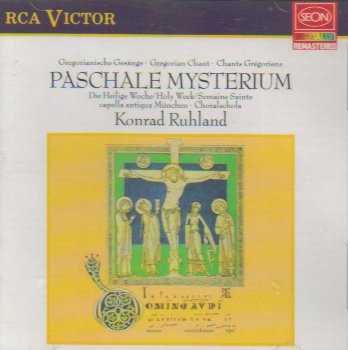

And hence also, perhaps, one of the many reasons why I was

unimpressed with the record at first listen over a quarter of a century ago.

Did Michael Cretu really think nobody in 1991 would have bought, let alone

heard, track two, side one, of the 1976 album

Paschale Mysterium by Capella Antiqua München (conducted by Konrad

Ruhland)? I myself had bought a copy many years beforehand to give my then

nascent assemblage of records a touch of the “exotic” – every student did that,

and if it wasn’t Gregorian chanting it was the songs of the humpbacked sperm

whale or Hildegard of Bingen – and so when I heard “Sadeness” (prissily

re-spelt “Sadness” for the buttoned-up British market) I shrugged my shoulders

and turned my attention elsewhere. The sacred and the secular; the chaste and

the proscribed, two sides of the same coin, etc.; I’d been there (musically and

artistically) before.

This is what I originally wrote on Popular about “Sadeness Part

1 (everything starts with an ‘e’)”:

The irony to note here is that New Age muzak, and other New

Age paraphernalia, are principally, if not exclusively, consumed by the kind of

person for whom spare time is an ample luxury, namely, amply rich people. Those

who really need stress relief tend to find it in other, more destructive ways.

“Sadness” indicates the benign, vacant tabula rasa which would become, in

spurious and gratuitous misreading of the KLF, “chillout” music, the equivalent

of an ice cube being gently lowered into a less pink Martini. Enigma was

Romanian synth musician Michael Cretu, who had been around since the seventies,

and “Sadeness” sets it all up – the soon-to-be-obligatory Gregorian chants and

whalesong, the polite Soul II Soul beat (though who would dance to it?), the prettiness

which could only arise from a profound misunderstanding of “Moments In Love,”

and a modest attempt to “subvert” expectations as a Dire Straits guitar revs

up, synthesiser chords pile up in a “threatening” manager and a Stars In Your Eyes Gainsbourg wannabe (N.B.:

Cretu says only that this was “a good friend” but he does sound like Cretu

himself, or, ahem, “Curly MC”) mumbles “Sade, dit moi…pourquoi le sang pour le

plaisir…le plaisir sans l’amour?…/Sade, es-tu diabolique ou divin?”

“Sade-ness,” you see – and the triple deep breaths which the female singer

takes immediately after that question answer it…this is shag pile music

masquerading as enlightenment, and about as enigmatic as Ernest Saves Christmas.

Full marks to Mark, however, for having a deeper go at the perhaps

not very enigmatic Enigma. What about his proposal that 1991 marked “THE YEAR

OF THE RETURN OF THE REPRESSED” – you could certainly categorise 2016 as such,

and by no means in a good way; if any lesson has been taught to us over the

last quarter-century, it is that it would be best for humanity if a lot of

things were repressed - ?

The problem with this theory from the perspective of the

album charts is that the latter more often than not seem to be the default

domain of the otherwise “repressed.” Most, if not all, of the acts Mark mentions

as returning to the top in 1991 as though from forced exile were actually TPL regulars in the eighties and in some

cases even the seventies. But the fabric of the market differed from even two

years before. For the several mega-acts who survived and prospered despite the

earthquakes which rumbled beneath them, they were to find that the nineties

weren’t quite the playground that the eighties had been for them. Now they had

a reduced share of the market, had to plead their case in steadily more

confining spaces.

But Michael Cretu had returned from the late seventies,

where he had been a bit player in

TPL

– we’ll get back to

them in this

piece soon enough – and a lot of what Mark says about the resurgence of what he

calls “Eurotica” is, I can vouch, absolutely true, including – or especially

including – the best bits, such as Aphrodite’s Child’s

666, which is sampled at several key stages throughout this album,

including on “Sadeness” and the Book of Revelations/end of the world stuff in the

“Rivers Of Belief” section. By the mid-seventies these roads had diverged but

it’s probable that Vangelis’

Heaven And

Hell LP and Demis’

The Roussos

Phenomenon E.P. were used for not dissimilar purposes. Nonetheless, the use

of Irene Papas’ expectant voice on “Sadeness” – in its original setting (the

track “∞”) she intones the refrain “I was, I am, I am to come” and everything

is as spelled out as, though far more thrillingly than, the average Judge Dread

single of the period.

One might say that such as veteran entertainers and

legitimate actors were compelled in seventies Britain to appear in sub-

Carry On pornographic movies in order to

make a living, there was no way forward for “progressive” musicians once the

dream was over except by making the apposite soundtracks. But the lines in progrotica

(as I messily call it) are less defined; listening to some of the period’s more

fanciful, less elusive music, one does feel that the musicians want to get a

leg over the universe as well as surf it.

To the album itself, then. It begins with a Charlotte

Rampling impersonator – actually one Louisa Stanley, then an executive at Cretu’s

label, Virgin Records* -

*and isn’t this actually spelling it out, from the totally

not ambiguous original label design inwards? Like, we did

Tubular Bells a generation ago – and indeed

TPL is not finished with

that

– when we were “all” eating cold baked beans straight from the tin in unheated

squats in Notting Hill…

…but now, when all these people have prospered, in great

part because they saw the Thatcher wagon coming at the end of that decade and

thought it was THE SAME THING as Branson – as, indeed, did Branson (in 1973 he

would never have entertained the tacky and seemingly numberless photoshoots of

later times) – the gaily-coloured NEW

THING coming to change and shake up dusty old toffs (people are still being

fooled by that in 2016) – who jumped on the self-loving eighties and exclaimed

THIS IS ME!, who were smart or poor enough to buy houses or flats cheap in

areas which would in the future become desirable, who are now rich and secure

in newly-gated “communities” which they would have found unaffordable a

generation before, and from which the generation following them would be priced

out altogether – well, for you SAME people, here’s a Tubular Bells for the NINETIES! All smoothed out, all the

disagreeable discrepancies ironed away…no barrow-spilling Windo discordant reed

honks to derail you**

**(and it is notable that Gary Windo himself passed away in

1992, younger than I am now, of an asthma attack. It was as if the world had

told him they didn’t want him any more.)

- and, as Mark says, this sounds like the introduction to a

yoga tape, or perhaps something more sinister. “Good evening. This is the Voice

of Enigma.” You almost expect her to be intoning “This is an Emergency

Broadcast from the BBC. Confirmation of a nuclear attack on this country has

been received…” “In the next hour,” the voice goes on, “we will take you with

us into another world…”

“This is a promise. For the next hour, everything you hear

from us is really true and based on solid fact.”

(Orson Welles, F For

Fake, 1973)

The voice does its best to hypnotise us – “Start to move

slowly…VERY slowly…” – and then we are into “The Principles Of Lust,”

incorporating The Hit. As for the alleged “panpipes” – which I initially thought

might have been sampled whalesong –they actually turn out to be sampled shakuhachi

flutes, the Japanese instrument which evolved from the Chinese bamboo flute of

the sixth century, popular with the Fuke sect (yes, I know) of Buddhist monks,

who used them not so much as musical instruments but as meditational tools.

This section also includes stock breakbeats, noises from wildlife and the

aforementioned hot apocalypse action of Irene Papas’ deep breathing.

Prog-Fusion would be a good means of categorising this

music. Like that damnable genre, it turns out to be all promise and no

deliverance, all expectations and no fulfilment. The tropes are set up – and nothing

is done with them, in order not to upset the newly rich neighbours. I imagine

Malcolm McLaren must have smiled at “Callas Went Away” and at how much better

he’d done this sort of thing (

and

helped popularise vogueing!) on

Waltz

Darling in 1989, an enterprise involving Actual Musicians who were Around

At The Time Of That Prog Dawn (Jeff Beck, Bootsy Collins, even David A

Stewart). Here we hear the great Maria singing what sounds like something from

Massenet’s opera

Werther – the aria “Ces

Lettres! Ces Lettres!” to be specific, while German pop star (and Mrs Cretu)

Sandra indulges in more deep breathing. The conflict between what is deemed right

to want and what is forbidden, perhaps? But it goes nowhere – the keyboards do

not sing, there is no reaction, no listening (thus the notion that this is the

first “major” album to be based around samples alone. But on something like DJ

Shadow’s

Endtroducing you are given

the notion that

everybody is

listening, or at least Josh Davis is listening to everybody).

It goes on. If the rainstorm at the beginning of “Mea Culpa”

sounds familiar, it’s because it has been sampled from the opening of the song “Black

Sabbath” by Black Sabbath – but, crucially, stripped of its shock, otherness

and, yes,

punctum, as though the

seventies were a crime for which we must all pay in one or another way (the

final nail in that socioaesthetic coffin is not the passing of Greg Lake – if

only Cretu were able to improvise, to genuinely

create [note the rhetorically-justified split infinitive], then he

might understand a bit of what

Tarkus strove to be about, which was the oddly logical juxtaposition of apocalypse and

comedy; hence it is entirely fitting that ELP should wind up writing songs for

Jim Davidson pantomimes, and if only poor Keith Emerson had better understood the

ramifications of his own juxtaposition he might have been persuaded to stick

around – but Kelly Osbourne asking the gay community to give Trump a chance.

That, more so than an overpriced repressing [omission of hyphen intentional] of

Never Mind The Bollocks crowding up

the window of a discount gift shop/chainstore on the King’s Road, is the

terminal cementing of Deadhead sticker onto Cadillac bumper). Instead of Iommi’s

crashing chords and Ward’s stumbling-out-of-the-apocalypse drumming – or even

the threatening bells – we get “Kyrie Eleison” and flutes.

The best track is “The Voice And The Snake,” 99 agreeable

seconds of dislocated non-tonality and non-rhythm; or, as I better know it, “Seven

Bowls” by Aphrodite’s Child. The breaking bowl leads to “Knocking On Forbidden

Doors” but instead of Peter Wyngarde making sick jokes in a variety of comedy

foreign accents, we are encountered with…yet more Gregorian chanting; “Salve

Regina,” without any acknowledgement of the crying children of Eve, mourning

and weeping in this land of exile.

Finally we get back to “Back To The Rivers Of Belief” and

catharsis comes apparently in the guise of…the Close Encounters theme, said in some quarters to have been inspired

by the philosophy (such as it was) of Sun Ra. But you will search in vain here

for a Marshall Allen or John Gilmore to blow the complacent temple down. As

with Escalator Over The Hill, earlier

themes and motifs return for a final bow, though to underwhelming effect. Instead

of the genuine catharsis of a Jack Bruce, we get a dreadful Renta-RockVoice

hack blurting out clichés with some even more dreadful Rock Guitar. Then the

inevitable Revelations stuff about the seventh seal and so forth (yet again sampled

from Aphrodite’s Child, I’m afraid) – and what, as the music blandly dies in

our underfed ears, have we learned? Without the remixes the record does not

even last an hour, nor do we hear the returning Louisa Stanley, like the voice

of Lowell Thomas surging through the finale of This Is Cinerama, telling us to switch off and hoping that we have

enjoyed our “journey.”

“I did promise that for one hour, I'd tell you only the

truth. That hour, ladies and gentlemen, is over. For the past seventeen

minutes, I've been lying my head off.”

(Welles, op. cit.)

The project appears to have been one where, quite apart from

confirming everybody as equals, all art has been confirmed as constituting

elements of the same beige broth.

The sleeve of the album contains three quotes; one from

Freud, another from one “Father X, Exorcist, Church of Notre Dame, Paris” (who

I’m not convinced actually exists) – and a misquote from Blake, demonstrating

how little Cretu has understood (if he has even read) The Marriage Of Heaven And Hell.

But perhaps in the sampled elisions of 1991 music, there are

more intriguing roads for Blakeisms to travel. That thing Mark said about “cheeky

sonic pseudo-magick” for example.

Love’s Secret Domain

appeared a little later in 1991 than Enigma, and to – at the time – little or

no notice, the mainstream music press already busying itself with prioritising a

refreshing return to basic, raw, honest, indie guitar rock. Its reputation

steadily grew in time, however, long after it had vanished from disinterested

record racks, and although it remains available as a download from Coil’s

website, the CD or cassette editions now command prices liable to cause your

bank manager to shudder. I don’t know where all these people were when dozens

of copies, priced at £1.99 each, were sitting in the cheapo section of

Selectadisc in Berwick Street for the best part of a year but there you go (the

only time I have ever seen it in a second-hand record store was in Toronto in

2007, where it was retailing for a mere forty dollars).

Anyway, the initial obligatory shrug of “another Coil album,

yawn” should be overcome because the record – its acronym should be obvious –

is a lot of things that the Enigma album isn’t; celebratory, humorous,

striking, provocative, consciousness-preserving, adventurous and at times very

affecting. It begins with a slow stutter of backwards effects, like a dormant

stomach reluctantly coming to life, before moving into an aural speed-read of

quickfire untraceable samples and functional jazz/New Jack Swing-lite beats

(“Disco Hospital”) before leading, via rocket launch noises and post-Tin Drum ritual gongs, into the first

“Teenage Lightning,” actually the first of three different readings on the

album of the same basic piece. This version is elementally the most basic of

the three – you do get the feeling of a younger and happier Joe Meek in the

Holloway Road knocking this up out of sheer Gloucester chutzpah – although I also note the extremely familiar bassline,

from Horace Silver’s “Song For My Father” (via “Rikki Don’t Lose That Number”),

a piece of music inspired by a trip made by its author to Brazil. Later on in

the record, the second version (“Teenage Lightning 2”) is perhaps the most “complete”

of the three, while the third (“Lorca Not Orca”) adds some Ibiza-friendly

flamenco guitar- that reading represents a crawl out of the tunnel of

suppression into bright freedom, all the more cherished for having been

harder-earned.

It is probably reasonable to note that, although the album

was systematically praised at and after the time for coming to terms with Acid

House, the two core members of Coil had a keener ear on dance music trends of

the time, and in many ways help anticipate some here, most noticeably in “The

Snow” – like Enigma, it uses Gregorian chants, but unlike Enigma it has purpose

and punctum. Some familiar-sounding piano work comes from Mike McEvoy – who once

appeared on Scritti Politti’s Songs To

Remember – which is a major relief following Cretu’s

minimalist-to-the-point-of-inertia piano “work” (Much of the Enigma album

suggests what Serge Gainsbourg, who died a couple of months after it came out,

might have sounded like minus all the Serge Gainsbourg elements).

Better still is the majestically patient “Dark River”

which three-dimensionalises ambient music to the point where it becomes its own

omnipotent, but living, statue or monument. Like Whistler’s Chelsea riverscapes

there are differing but related details in the far distance, in the

middleground and close up, and all are captivating and transcendent. As with

later masterpieces from its decade such as Aphex Twin’s “Stone In Focus” and μ-zik’s

“sick porter,” it transfixes its listener with modest imposition, and could be

as old and timeless as the song of the gods.

Other highlights include “Titan Arch” which guest singer

Marc Almond holds together through sheer strength of character as the music

collapses loudly around him (“Under shivering stars/The sickness is gliding” –

it was probably the most avant-garde Almond had been since Psychic TV’s “Guiltless”;

Peter Christopherson evidently understood him the way so many other musicians

and producers didn’t). “Windowpane,” sung by Jhon Balance himself, suggests the

Moody Blues outlook escorted towards a further dimension (“If you want to touch

the sky/Just put a window in your eye”), but his mainly

monotone-with-brushes-of-exclamatory-revelation vocal style actually points a

finger directly to what Karl Hyde would be getting up to with Underworld just a

couple of years later. “Chaostrophy,” despite its terrible title, is an

absorbing passage from slowly-decaying elements of what might once have been

described as “music” to a peaceful, oboe-led pastorale, as though the light had

finally been reached and attained.

But even this music is not free of its own clichés. Little

Annie (a.k.a. Annie Anxiety Bandez./etc. – her 1987 Adrian Sherwood-produced

album Jackamo, currently available as

credited to “Little Annie,” is ridiculously yet merrily ahead of its Björk/Goldfrapp

time) turns up for “Things Happen” and has a nice time in the standard Grace

Jones/Marianne Faithfull role of the woman of vague European origin caught in

an exodus, or a riot, or is it just her backyard, last helicopter out of the

embassy etc. (despite somebody – Balance? – uttering a desperate cry of “Kill

the Creator! Send them the Bomb!” right at the beginning) chit-chatting

semi-drunkenly with an old friend in Ohio

(not Scott Walker or Chrissie Hynde) but there is definitely a 1983

heard-this-all-before feel about the piece. “Where Even The Darkness Is

Something To See” is three or so minutes of pointless didgeridoo ambience (and

not a patch on Aphex Twin’s “Digeridoo”). The listener’s ears strain to

identify the dialogue at the beginning of “Further Back And Faster” but sadly

it turns out to be from that old Video

City indie standby Performance, and once we get to the HATE

and LOVE tattoos on the knuckles it is definitely Saturday all-nighter at the

Scala time.

Mr Balance brings the proceedings to an end with the title

song. He cites Blake again (“O Rose thou art sick” although we get an agonised “URGH!”

from the vocalist rather than invisible worms flying in the night) as well as,

very predictably, Orbison’s “In Dreams” (not scary). It’s quite enjoyable in a

tittering-to-onself way but overall, I would say, ends the record rather

flatly. There has to be another solution.

Beyond its cover – and the subtextual notion that, with at

least some Pink Floyd, musicians in the nineties were knocking on

still-forbidden doors –

Chill Out

doesn’t really have much to do with

entry #83, even though it appeared in the

context of a similar period for music and art, one that KLF biographer John

Higgs has termed the “liminal” period, where nothing and nobody really is in

charge or setting the pace, and hence where anything and anybody can really

happen and have some degree of an impact.

For the KLF this was the interregnum

between Acid House and Britpop – a point at which some claimed proof that

evolution was reversible – and the fact that throughout the early nineties, and

during the year 1991 in particular, they were in commercial dominance. The moot

point, they might have observed, is whether things were so up in the air that a

couple of merry art chancers like Drummond and Cauty could be permitted to have

their way.

Yet

Chill Out –

the KLF’s first non-compilation album under that name – can’t squarely be

placed in any tidy “tapestry” or “canon” of pop or rock or even dance music

history. In an interview at the time, Drummond explained that the purpose of

the record was to act as a soundtrack to

the

day after a rave – when everyone and everything had packed up and gone and

all that was left was the countryside. Remember what I said about

Our Favourite Shop being music for the

day after defeat – and let us not even think of the 1983 American telefilm

drama

The Day After, starring Jason

Robards – and consider that these forty-four minutes of music might signify the

day after a victory (albeit possibly a temporary, pyrrhic one).

There isn’t much to

Chill

Out, and yet there is everything to it – enough, at least, to convince me

that this music avoids the traps in which both Enigma and Coil encase

themselves. Superficially, it is the aural soundtrack to a journey, one made

across the Deep South of the USA, specifically along the Gulf Coast – but, as

Drummond later admitted, he and Cauty had never been anywhere near Louisiana or

the Tex-Mex border (at the time) and the names and descriptions were picked

randomly from an atlas, the whole being allegedly recorded in two days on

anything that wasn’t nailed down in the basement of Cauty’s squat in Stockwell.

However, as Dolphy once astutely noted, once the notes are

in the air, released, they are for us to breathe, and this

Chill Out still seems to me to answer a lot of questions about ways

of hearing which both Enigma and Coil avoid (intentionally and unintentionally,

in that order and in my opinion). On the face of it, nothing much happens

during the record; we hear the sounds of the outdoors, trains whistling by,

automobile engines on the road, the distant noises of nature, the transient random

noise bursts – or, to put it more precisely, drifts, like the continental drift

– with announcements. Songs and radio broadcasts loom, shift into momentary focus

and disperse into space.

From the point of view of an American journey, and given the

multiple voices and references to other songs within its structure, Chill Out may even be compared with

Brian Wilson’s SMiLE insofar as this

may be the soundtrack to the journey of the electronic bicycle rider. There are

long and languid passages of pedal steel, courtesy of “Evil” Graham Lee of the

great Perth

band The Triffids – and consider what we heard on the very first song on their

album The Black Swan from the

previous year:

“And from this window, I can see the street below

I can hear the hit parade on the radio

There's dirty dishes piling up in the sink

But it's too hot to move, and it's too hot to think.”

A similar feeling pervades Chill Out. Not until we reach the second half does anything

approximating a beat appear, and then only relatively momentarily. There are

separate reasons for that. But all is not as it might seem. On the radio we

hear a growling man yelling to someone unspecified about the kingdom of God and

money (“You have so much money, you’re gonna get scared”). There is a news

report of a fatal and bloody drag racing accident (“His body was pulled from

the car by a passing motorist after which the car, in flames…destroying stores...”

– it sounds like the last broadcast). We get a Bible quote (“Be of good courage

and be of good comfort,” inevitably making me think of Welles’ “Be of good

heart, cry the dead artists out of the living past” in F For Fake), a DJ voiceover and that growling man again, who now

reveals himself to be a rather ominous-sounding preacher (“Bronx New York! Get

on the telephone! Call 50 of your friends! Tell all your friends who need some

help! Doctor Williams comin' to the Bronx New York…I’m talkin’ to you, baby, I’m

talkin’ to you, sucker…”). We also

hear broadcasts from Russia

and Britain.

Another layer of Chill

Out is disclosed with some hindsight. At the time of its release in

February 1990, the KLF had had no hit singles - if you discount “Doctorin’ The

Tardis” – but the music here subtly signals to us what is to come. There are

references to, amongst others, “3 A.M. Eternal” – the bathysphere bleep becomes

a moving siren to lost drifters everywhere – “Last Train To Trancentral” and “Justified

And Ancient.” It is a disguised greatest hits compilation before the hits had even happened or existed. Had anybody done this

with pop before?

There are recurring electronic motifs, but also…the sound of

pop music, the aura that it gifted on those listening in prefabricated post-war

bedrooms, or tuning into pirate stations on their Walkmen. In many ways, Chill Out commemorates lost pop, and maybe some of its

umbilical ties to what became progressive rock – there are Peter Green’s

Fleetwood Mac, playing “Albatross,” that unassuming Santo and Johnny in Chess

Studios tribute that needed so words and whose tom-toms sounded like the

biggest possible heartbeat, which the Shadows wished they’d thought of first –

they split not long after the record came out – which went to number one

towards the end of a decade where everybody was beginning to feel lost, whether

the crippled, dying Vietnam vet of “Ruby Don’t Take Your Love To Town” or the plaintive,

self-sacrificing father of “The Deal.”

In that latter chart – almost the last of the sixties – we also

find “Oh Well” by Fleetwood Mac. A year after “Albatross” and Peter Green is

clearly troubled. But the elements which turn up on Chill Out are those of the seldom-played “Part II” – the slow,

patient guitar adagio with eventual

Morricone-type orchestrations, from the album which helped give Then Play Long its name. As with some of

Derek Raymond’s protagonists, one gets the feeling that Green is approaching

his willed burnout, his end (and yet, at the time of writing, everybody

involved in that record is still alive and well!).

But the aura here is increasingly troublesome. Also from

1969 we hear, in the distance, Elvis with “In The Ghetto,” and I am back in my

orange sunlit bedroom, lying on my bed and listening to Fluff Freeman counting

down that week’s charts, absorbing what is going on and attempting to make some

kind of sense out of it before dinner is ready. The lost Elvis, or the Elvis

who temporarily found himself before becoming lost again, singing a song of

loss, about losing even by being born (Bobby Womack plays the guitar) – the lost

past, coming back into focus. Other interjections, such as the repeated “After

the love has gone,” come from a Boy George record (“After The Love” by Jesus

Loves You), remind us that somewhere it is turning into the nineties.

There, however, unmistakeably coming into view, the source

of all the pain – “Stranger On The Shore,” a hit record before I existed and

one of the first pieces of music I learned to play. The tune was not specifically

written for a children’s television series – it was initially called “Jenny” in

honour of Acker Bilk’s daughter – but was used as the theme to one. Stranger On The Shore was actually about

a young French au pair coming over to

live and work in Brighton and having to deal with the striking cultural

differences (one of its leading actors, Richard Vernon, would later appear in The Hitchhiker’s Guide To The Galaxy)

but the music far outlived the show’s premise and became a symbol of the

wonderful new world that 1962 seemed to promise (prior to the brutal

near-quietus in October), a future that promised to be better than the one

which people got, and yet the record was also a connecting vessel to the past –

the unexpected and ambiguous final chord change suggests “Sleep well, Britain”

as surely and uncertainly as Mantovani’s “The Theme From Moulin Rouge” had done nine years before.

“Stranger” was also heard on the Apollo 10 lunar module and

perhaps its reappearance on Chill Out

signifies a marooned satellite, doomed to orbit around our sky forever. But

this is largely a story of pop without the rock ‘n’ roll – until right at the

end, when we hear a looped guitar figure which turns out to be a sample of “Eruption”

from the first Van Halen album – Van fans will know that this segues straight

into their “You Really Got Me” – which in 1978 was the nearest most of America

got to “punk rock.” Above them we hear the reassuring tones of Tommy Vance – “Rock

radio…into the nineties…and beyond…”

But wait! Tommy Vance? Out here on the Gulf Coast?

And what are those Tuvan throat singers doing there…and when did we hear sheep

in the Deep South? The cover betrays more than

it thinks you know, for towards the end of the album, although we still hear

interjections from,

inter alia, Jerome

Moross’ theme to

The Big Country, we

also hear the sound of a very un-American rain and windscreen wipers – and we

realise that it has become dull and overcast and that we have been in

grim-up-north-and-south Britain all the time. The incremental autumn is as

unexpected and moving as the second side of

New

Gold Dream. The journey moves on, but at an increasing distance, as though

the disappearing world were saying goodbye.

In retrospect, it is probably best to view Boney M as an art

project. Here is a world where the base matter of pop music – be it “No Woman

No Cry” or “Heart Of Gold” or “My Cherie Amour” or “Have You Ever Seen The

Rain?” or even “Dreadlock Holiday” – is treated as a catalyst for commentary on

pop music. The concept probably rocked better than the reality, but from “Nightflight

To Venus” onwards there was this obsession of escaping the world, the planet –

and a few years later in the eighties something like “Exodus (Noah’s Ark 2001)”

will reinforce this urge.

Boney M – a group whose backing musicians once included

Michael Cretu – were, as far as Britain was concerned, on a dying fall in 1981.

An album with the unwieldy title of Boonoonoonoos

was recorded, but by the time of its release Bobby Farrell – effectively the

mouthpiece of the group’s creator Frank Farian, in a Charlie McCarthy sense –

had left or been fired (depending on whose story you believe) with no

meaningful group left to promote the record.

No doubt “We Kill The World (Don’t Kill The World),”

released in November 1981, had its eye on a late Christmas number one, but it

wasn’t to be – without promotion and with the single too long for regular radio

airplay, it stalled at #39, and the group did not register another original

single in our Top 40 thereafter. The song comes in two parts – the first begins

with some odd, deep electronic thunderclaps, and then Farian’s voice of bass

doom enters: “I see mushrooms. Atomic mushrooms. I see rockets. Missiles in the

sky.” It could almost be Killing Joke.

The music builds up and then breaks into…an early Bucks Fizz

trot. The singers bark out protests against the destruction of nature, etc.

before a curiously uplifting-sounding chorus. This carries on for a bit before

it stops dead, and then a child’s voice, having some problems with pitching,

enters with a plaintive “Don’t kill the world” plea. He is joined by a children’s

choir – actually it was just two singers, Brian Paul and Brian Sletten, plus

lots of overdubbing and then we get into a “We Are The World”-anticipating

handclap hymn song.

One understands what Farian is trying to achieve here, but

the English-is-not-one’s-first-language trope is harder to overlook than Abba

or Kraftwerk. “Do not destroy basic ground,” “Don’t just talk/Go on and do the

one,” “Pollution robs air to breathe” – there is a fumbling sense to all of

this which is quite touching but the production holds back too much, the rock

guitar stays in the background and aesthetic salvation isn’t quite attained. “The

Land Of Make Believe,” which Bucks Fizz released in the same month and which

went to number one in the New Year, is much tougher, scarier (there is no real

happy ending) and overall hipper. Nonetheless, this is one of the roads which

leads to Enigma – an artefact whose religion isn’t holy, whose sex isn’t sexy,

whose music is more wallpaper than music. Ultimately Enigma failed because its

creator couldn’t keep his eyes off the mirror. Coil at least endeavour to

trespass and question, and even have some worthwhile fun in the process. But if

you want to know why the world shouldn’t be killed, in the last two seconds

when you might only have time to notice the sirens sounding, then Chill Out – of all artefacts! – best maps out the reasons why it, and life, and

progression and punctum, might still matter. We simply have to reach out – and find

our ways of listening.

.jpg)