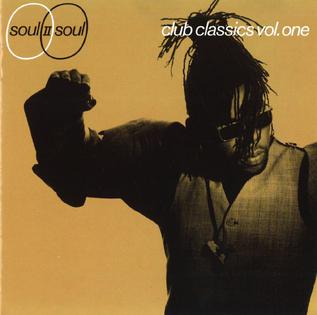

(#392: 15 July 1989, 1 week)

Track listing: Keep

On Movin’ (featuring Caron Wheeler)/Fairplay (featuring Rose Windross)/Holdin’

On/Feeling Free (Live Rap)/African Dance/Dance/Feel Free (featuring Do’reen)/Happiness

(Dub)/Back To Life (Accappella; featuring Caron Wheeler)/Jazzie’s Groove

Did you watch, or listen to, the BBC Proms Grime Symphony

last night? Fantastic, wasn’t it? Justification in itself for the licence fee,

I’d say (together with the earlier and equally fantastic

Boulez/Ravel/Stravinsky programme). There they all were; established giants

like Lethal Bizzle (whose orchestral “Pow!” is one of this millennium’s

greatest musical moments thus far, as succinct and direct in its way as Michael

Mantler and Pharaoh Sanders’ “Preview” was forty-seven years ago), Wretch 32

(when “Something” finally makes it to record, he should do it like this) and

Krept and Konan, who recently and narrowly missed out on a number one album

(but this blog has its ways), together with newer names like Stormzy,

Lewisham’s superb Fekky (a slightly more placid Giggs) and the sensational

Little Simz (“ROYAL ALBERT FUCKING HALL MAKE SOME NOISE!!”). Throw in guest appearances by Shola Ama and Kano, plus

Jules Buckley’s brilliant orchestrations (like Todd Levin if he’d meant it), and

somebody called Chip who turned out to be the long-lost (and dramatically

revitalised) Chipmunk, and the whole was pretty unassailable.

Of course there will be the purists – who when it comes to

black music are invariably middle-aged white men – who will argue that last

night’s music was not “true” grime, not like in the golden 2003 days, but

frankly, sod them; Puritanism should have died with Cromwell. We know from the

past how awkward these musical meetings can sometimes be but there was nothing

awkward about last night’s music, which represented the consolidation of the

long march which British black music in particular has had to undertake.

At such a point it is salutary to remember where it all

started. I sat looking at another example of what some music writers still

refer to as “landmark albums” – and if you’re going to call your debut album

anything (if it’s a calling card, which it should be) then call it something

like Club Classics Vol One; to hell

with kow-towing disguised as self-deprecating modesty! – and wondering how I

was going to write about it. I know that absolutely nobody is going to welcome

another opportunity to gather round and listen to Grandpa Punctum telling you

another story about the good old days and how great they were and how terrible

things are now, because that gets nobody and nothing anywhere.

Still, what do I

say about Soul II Soul that you can’t find out for yourself in the Wikipedia

entry or in the sleevenotes to the 10th Anniversary Edition of Club Classics? If you want a detailed

examination of the multi-threaded socio-political history which led to “Keep On

Movin’,” read Paul Gilroy’s absorbing The

Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness but agree with its

central point that Soul II Soul, and “Keep On Movin’” in particular, represent

the moment when British black music started to answer back and influence what

was happening on the other side of that ocean.

You could argue that the story of Britfunk and British soul

remains the secret story of the eighties. The explosion presumed with the

emergence, in and around 1981, of the likes of Light Of The World, Beggar and

Co, Incognito, Imagination, Central Line, Junior Giscombe and Linx - supple,

rhythmic and utterly relevant - never really came to pass, despite the best

efforts of the Norman Jays and Paul Wellers of that world, and by the

mid-eighties the "movement" as such had dwindled to a hardcore

fulcrum on which balanced the likes of Loose Ends and I-Level. Although the

former in particular were a group of rare power and originality - "Hangin'

On A String," though produced by the American Nick Martinelli, remains one

of the greatest and most startling soul records ever to emerge from a British

studio - the fluffier teenpop variant of Five Star was the preferred mainstream

option.

But the story, though relegated to the background, remained

a vital undercurrent; both Camden's Soul II Soul and Bristol's Wild Bunch

developed an awesome reputation through their sound system DJ all-nighters,

utilising their love for the undertold story of eighties pop - an eighties of

Odyssey's "Inside Out," Evelyn King's "Love Come Down" and

Thelma Houston's "You Used To Hold Me So Tight" which still hasn’t

received its just dues (think of Dennis Edwards’ “Don’t Look Any Further” as

the movement’s very own “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction”) - and mixing it with

the residue of spirits from dub and post-punk to work towards a mix which could

rightly be claimed to be their own art, their

music.

To appreciate the full impact of "Keep On Movin',"

the third Soul II Soul single but the first one to cross over into the Top 40,

you really needed to have ambled through the imposing terraces of West London

in that enlightened spring of 1989, since the overwhelming impression given by

the record is one of elegance - an unhurried walk through the patience of

reason. It slowed pop back down, made it breathe again rather than

hyperventilate, even if the "keep on movin', don't stop" motif had

social directions in mind; it was the perfect soundtrack for an idle wander

around the outskirts of the Circle Line on an empty, cloudy Bank Holiday

Monday, but much, much more as well.

But the story of Soul II Soul is specifically a North-West

London story; Jazzie B is from Hornsey via Antigua, and it all came together in

Camden. “Keep

On Movin’” makes me think of Camden as it once was, and indeed the number 24

bus you took to get there (and beyond, to the threshold of Hampstead Heath).

Unlike now, when the 24 is just another anonymously corporate red bus, the eighties

24 had art; it came in shades of turquoise and dark green. It didn’t look like any other bus and it could

take you from the centre of town in a matter of fifteen minutes.

In those days Camden

was a place worth going to; Compendium Books, almost directly across the road

from Rhythm Records, and so many others (you can find them elsewhere if you dig

a little). You’d travel there of a weekend with absolutely no idea of what

you’d find or where you’d find it. And so when I hear Caron Wheeler singing, delicately,

“Yellow is the colour of sun rays,” I not only think of the black gold of

Rotary Connection but also what it felt like getting there, and coming back, on

the 24 bus (in fact, taking Jon Savage’s atmospheric sleevenote into account,

one could consider Saint Etienne’s Foxbase

Alpha as a very belated parallel to Club

Classics, albeit using a partially different series of reference points).

Those of us who were present at the time recognised how

important these first two Soul II Soul singles were going to be. You couldn’t

walk through London

in 1988 without hearing “Fairplay” or “Feel Free” blaring out through

somebody’s car stereo or on an elusive pirate radio station. Even if you don’t

think you know them, you do; one listen to Rose Windross’ “Bay-BAY! Bay-BAY!

Bay-BAY!” on “Fairplay” should uncloud your mind (I can think of at least one

other long-term resident of Hampstead and Highgate, and of Then Play Long for that matter, who was knocked out by that

record). Meanwhile, “Feel Free” plays like a virtual blueprint for what the

early Massive Attack would practise; ominous Reggae Philharmonic Orchestra

strings, hip-hop beats which don’t have to bang on your head to prove their

nowness, a direct and hugely disturbing vocal, as though threatening to shatter

complacent glass forever (“Every day I look into the mirror and I see

my-SELF!”), by Doreen Waddell, whose awful and entirely avoidable end can be

looked up on Google. Unplayed on mainstream radio, unmentioned in the music

press (though not in the fashion press; Soul II Soul sold clothes as well as

club nights and records) – you either knew about these things or London wasn’t

for you, much as the crowds at the Albert Hall last night enthusiastically sang

along with, and knew every word of, joints which as of now exist only as

downloads. This was the triumph of the music played at the back of the bus.

But “Keep On Movin’” was different,

even (or especially) from the rest of what then constituted British soul or

hip-hop music. “Don’t stop like the hands of time,” warned the song. “Click,

clock, find your own way to stay” (the whip is in the grave, as The Band once

sang; the world is now yours); “Why do people choose to live their lives this

way?”

Those Oriental strings out of Chic. The courteous chutzpah

worthy of imperial phase Prince. “The right time is here to stay,” “I hide myself from no one.”

It was black Britain’s

“Anarchy In The U.K.” except it had something more to offer than nihilism.

Sure, one major purpose of this group and record was to promote

a clothes shop. Wasn’t that the case with the Sex Pistols?

Indeed, you could propose that Soul II Soul demonstrated the

only successful example of British popular music crossing over into business

and making a go of it. Remember all that mock-corporate talk in the early

eighties; Rhythm Of Life tinned peaches and what have you? I think some of

these New Pop people wanted a piece of the action, really. Well, Jazzie B went

ahead and did it, and maybe the Soul

II Soul story is what Thatcherism should always have been about; the little

person building up something from nothing and thriving instead of surviving.

The trouble was that the other side

of the coin – the one which talked about giving something back to your

community once you had become successful, rather than keeping the profits for

yourself – was, and for the most part continues to be, disregarded.

In this respect, Club

Classics plays like a travelogue of late eighties London, a Camden Duck Rock, if you will (Jazzie B’s

occasional pronouncements throughout the record do remind me somewhat of

McLaren, but the Zulu musicians are far more subtly deployed, particularly in

“Holdin’ On”); through its (just under) forty-five minutes you hear Deep House,

hip-hop, the influence (though not the presence) of reggae, jazz (flautist

Kushite has a ball on “African Dance”) and flashes of what else was good about

those times (the staccato brass fanfare samples dotted throughout “Feeling

Free”). The prototype of “Back To Life” is mainly Caron Wheeler and backing singers,

but the tension keeps subtly building up, and when the deep beat bursts in it

feels like a moment of liberation, of profound release, as well as immense

exultation. Jazzie B himself brings proceedings to a close as he talks about

the history of Soul II Soul and where he’d like it to go.

I listened to the cassette of this album on my Walkman all

over London (I

still have it, and it still plays perfectly). But you have to go to the 10th

anniversary edition CD (which I found – and it was only right to find it there

– in a charity shop in Hampstead) for the single of "Back To Life," which

represented Soul II Soul’s moment of eternal summer. Despite the lyric's urges

of "back to reality" and "back to the here and now" (yeah)

there seems something wonderfully unreal, something evocatively 1967, about the

record's straight delineations; as with "Time Of The Season" the

absence of a musical centre - no guitars, hardly any chords or harmonies except

for the occasional and thoroughly relevant interceptions of piano - widens the

song's emotional space. For large stretches there is nothing to the record

beyond Caron Wheeler's sublime, expansive lead vocal, a bassline and a drum

program, but its movement remains sultry, decisively carnal but sociologically

generous, coloured in at precisely the right moments by those Oriental strings –

again, brilliantly remembering their Chic - drawing watery lines of art across

the song's benign canvas. Wheeler, too, is patient: "However do you want

me, however do you need me" - she both wants and needs her Other, but she

is prepared to wait, smiling and welcoming (despite her "Let's end this

foolish game" asides), until he's fully ready to embrace her spirit.

Of course, such references as "take the

initiative," "make a change, a positive change" and "I live

at the top of the block" (though the piano chords accompanying that line

are the record's punctum – keyboardist Simon Law is the album’s unsung hero) suggest

a wider agenda. It may well be that Club

Classics succeeds so well because of the elegant (there’s no other word to

describe it) programming work of producer Nellee Hooper - the far from missing

link between Soul II Soul and what was about to evolve from the Wild Bunch into

Massive Attack - whose intimate and instinctive understanding of space and

structure helped lead to the latter's string of masterpieces, starting with

Neneh Cherry's startling "Manchild," also a top five hit that spring

(a co-production by Hooper and Cameron McVey, who between them paved the way

for New Pop Mk II). But "Back To Life" stands tall as the last great

number one of the eighties, summer seeping through its grooves like honey

through a brightly coloured ladle of hope.

Me? I think that art in whatever way you want to frame or

describe it is markedly better in London

now than it was back then. And the centre of things may have shifted eastwards

from Camden to

Shoreditch. And London

may on the face of things resemble a

less friendly and open place than before. There are no Soul II Soul shops now –

Camden has basically been reduced to a tourist trap – but their clothing

imprint (“Funki Dred”) can be found at Harvey Nichols, just down the road from

the Royal Albert Hall, and that must signify a real achievement, something

better than what came before. And as far as Camden record shops are concerned; well,

there’s another one which should be mentioned – Rock On, just next to the tube

station exit (and also now long gone), to some people about as unhip as late

eighties record shops could get, but I found some good things there. Once I

came in and bought a copy of the theme tune to Fireball XL5 (which I note was sung by the man who is currently

Russell Crowe’s father-in-law) and I was wearing a suit (because I liked

bright, colourful suits in the eighties), though was certainly dangling no car

keys. I know for a fact that Nick Hornby was a regular customer at Rock On, and

that the shop in High Fidelity was in

large part based on Rock On. In the book the main protagonist says this about a

customer who comes in and buys the theme tune to Fireball XL5, wearing a suit:

“Do I want to be like him? Not really, I don’t think. But I find myself worrying away at that stuff about pop music again, whether I like it because I’m unhappy, or whether I’m unhappy because I like it. It would help me to know whether this guy has ever taken it seriously, whether he has ever sat surrounded by thousands and thousands of songs about … about… (say it, man, say it)… well, about love. I would guess that he hasn’t.”

You might want to think of my fifteen or so years of online

and printed music writing as an extended response to, and pronounced negation

of, that rhetorical question.