(#387: 20 May 1989, 2

weeks; 10 June 1989, 2 weeks)

Track listing: Too

Many Broken Hearts/Nothing Can Divide Us/Every Day (I Love You More)/You Can

Depend On Me/Time Heals/Sealed With A Kiss/Question Of Pride/If I Don’t Have

You/Change Your Mind/Too Late To Say Goodbye/Especially For You (duet with

Kylie Minogue)

The other side of a not terribly interesting story; while

Kylie sings about generally being a doormat, here’s the boy desperately trying

to persuade her, or us, that no, he means it, and yes, he loves her even though

he’s always away, and no, there’s nobody else, and…well, you can judge from the

respective album covers; Kylie smiling against a virginally white background,

and Jason, in front of a blood red wall, looking perturbed as though just

having been caught out.

The key may well lie in the first song: “Too Many Broken

Hearts” can be interpreted as a last-ditch don’t-leave plea or, if you look at

it from another angle, the first number one song about impotence since “Band Of

Gold” (“Last night I tried to reach you/But somehow it wasn’t enough,” “"So

I said, can't you wait a little longer?/I'll give you all that a lover should

give"). The song demonstrates, for all SAW's talk of nowness, a

surprisingly traditional gait; with only minor alterations in its arrangement,

"Too Many Broken Hearts" could have been a hit for the Fortunes in

1965, with its endemically catchy "You give me one good reason to leave

me/I'll give you ten good reasons to stay" tag. Shielded by layers of

protective double-tracking, speed slowing and backing vocalists, Donovan gives

a reasonably lusty reading...of a song which is supposed to be about

desperately holding on, in more than one sense.

The trouble is that when Donovan exclaims "I'll be

hurt, I'll be hurt, if you walk away" he appears to regard this

"hurt" as being on a par with bumping into an errant doorknob, and

given that the song may then venture

into "Band Of Gold" territory, he sounds more than ever like a

confused teenager who hasn't quite worked out which end to hold. The chorus

also lets the song down somewhat with its hackneyed "I won't give up the

fight for you" meme. The whole is like a gaudily coloured Commonwealth

jigsaw puzzle whose pieces never quite seem to fit.

Throughout the remainder of side one he protests his faith

perhaps a little too much; “Every Day” sees Donovan anticipating Bryan Adams (“’Cos

everything I do, I do it for you”) and its bathetic plea of “I may be working

overtime” recalls not only “Always On My Mind” but emphatically also Hot

Chocolate’s “Emma,” whose protagonist, you may recall, spends so much time

working overtime that he’s never there for Emma when she needs him. “Nothing

Can Divide Us,” the album’s best song, is sung with such an air of bafflement

that it hides how strange the song really is – “You can put your faith in me/I

will never set you free”; what kind of reassurance is that? Herein lies another

central problem; although Donovan is technically a reasonably competent singer,

so much so that you don’t notice that “Nothing Can Divide Us” covers some

three-and-a-half octaves, I have heard Rick Astley’s isolated guide vocal track

for the same song and his voice thunders

out its message; he knows how to project

a song, whereas Donovan sings the notes, so to speak.

Like other SAW albums, the music gets a little headachy

after a while with its benign hammer of repetition – although, with SAW, one

has to remember that they regard the comment “all the songs sound the same” as

the highest of compliments. There are no doomed adventures into daytime Jazz FM

land, but the music simply doesn’t let off, hasn’t given itself room to

breathe. By the time the side limps to its closer, “Sealed With A Kiss,” one is

reaching for the paracetamol.

Brian Hyland's 1962 recording of the song is a record of unalleviated

bleakness comparable with "Johnny Remember Me" and "Ghost

Town." While Carole King attempted to put a brave, jolly face on the same

issue in the same year's "It Might As Well Rain Until September," the

five-note dies irae of the opening

guitar figure, the distant harmonica and the unreachable wraiths of female

backing voices all contribute to the singer's sense of dazed dread that

September may never arrive, or that his love is already lost (the sequel to

"Sealed With A Kiss" did eventually arrive five years later in the

Velvet Underground's "The Gift," a warning that unilateral cherish

always has its inbuilt limits).

Hyland sings with the chill of death flowing within his

teenage veins, since of course to such teenagers even summer holidays from

school are a matter of life and death. Although there is no evidence in the

song that any of the singer's idolatry is reciprocated, the most charitable

remark I can make about Donovan’s version is that he sings it as Max Bygraves

might have sung it; the right notes - well, approximately - but with a complete

(verging on detached) lack of attachment to the emotions the song tries

meta-clumsily to articulate. It is all done on one, not even especially morose,

level. At the song's climax of "You won't be there," and "I

don't wanna say goodbye," which Hyland sings as though having just slashed

his wrists with fragments from his newly-broken mirror, Donovan can't even get

his timing or phrasing right.

His performance is therefore something of an innocent

insult. But naturally such concerns failed to register with his fans, most of

whom were not old enough to remember Donny Osmond, let alone Brian Hyland, and

who ensured that his "Sealed With A Kiss" became the first

non-charity single to debut at number one since "Two Tribes." But

even this achievement signals the beginning of the decline and devaluation of

the singles chart. In the same week there was also a new entry at number two -

"The Best Of Me," Cliff Richard's 100th single, and heavily promoted

as such, although it was an instantly forgettable routine ballad - and although

Cliff's hundredth single attained the same peak position as his first, thirty-one

years previously, both he and Donovan dropped down and out of the charts fairly

rapidly, and neither record has survived on oldies radio or endured in any

other noticeable way. The ground was therefore laid for the charts to becoming

yet another marketing tool as opposed to a genuine representation of the

public's musical likes at any given period (though some would believe, not

without reason, that 'twas ever thus); instant results became required, and by

the mid-nineties a first week number one entry would become more or less

obligatory for any would-be chart-topper. Thus the stage was set for the

rotating passing fancies of a few thousand people rather than for genuine

future classics; and thus the overall decline – in the singles chart rather

than in SAW’s work; that is yet to come - begins here.

Things get darker, but no better, on side two; now boy and

girl appear to be breaking up but the musical merriment is so remorseless and

one-dimensional that it’s hard to recognise emotions. Listening to this, its

year’s biggest-selling album in Britain,

is like being made to eat a dozen sugary chocolate éclairs in a row; it is not

long before nausea becomes dominant. While SAW took pride in comparing

themselves with Motown, the non-differential attitude is a fallacy; Motown may

have been a churn-‘em-out hits factory but its best records depended on a

matrix of musicians who not only play the notes they’re given but are also

given the freedom to play with them.

There is no James Jamerson or Paul Riser in SAW’s work, and drummer “A. Linn”

is far from being Benny Benjamin.

Actually, the further you listen to Ten Good Reasons, the crappier it becomes. One is hit over the

head, “Mule Train”-style, by song after interchangeable song, insubstantial

trifles which I forgot even as I was listening to them. Donovan’s “Change Your

Mind” is no Sharpe and Numan (nor is it even a cover of that song), while “Too

Late To Say Goodbye” is really a very nasty little song. As with Level 42’s “It’s

Over,” he’s gone, left her only a letter, but where Mark King is consumed by

the pain of his own guilt, Donovan, the staunch Gabriel Oak who has throughout

this record proclaimed his stalwart faith, suddenly announces that he’s found somebody else (“Who gives me all

that I need, not like you”). As he

merrily rolls away cheerfully singing “I won’t be there watching you cry,” it’s

perversity worthy of mid-seventies Lou Reed. It is also the album’s tenth song

and its natural closer; here the mask drops and Kylie was right – he really has been a shit all along.

But it’s not the end of the album. Tacked onto its end – and

it must have been tacked on – is the

big number one duet with Kylie, and suddenly they are together again and happy

again and in the context of this record it makes no sense whatsoever. The

photograph of the pair suggests a Dickie Valentine and Alma Cogan for their

age, but where Kylie is clearly A Star, Jason just resembles a grinning dork

(Dick van Dyke? Richard Chamberlain? Stan Laurel?).

With professional perfectionism SAW had put the two of them

together for a romantic duet to coincide with the broadcast of Scott and

Charlene's wedding in Neighbours,

watched by in excess of twenty million Britons. "Especially For You"

still had to wait a month at number two behind "Mistletoe And Wine"

before ascending to the top, but somehow that was seen as a polite gesture in

itself, since the song and performance are so unambiguously nice and wholesome,

and it was clear that SAW were setting Kylie and Jason up as the Donny and Marie

of their day, without the troublesome subtext of brother and sister singing

tender love songs at each other.

The song sees them reunited after an unspecified spell

apart, and it is handled with such delicacy; on TV they performed a courtly

little dance routine to accompany it, and the overall air is one of a Christmas

pantomime duet between the two romantic leads. Kylie clearly takes the lead;

her "mmm"s and "ooooh"s leading into the build-up to each

chorus are skilful and emotionally connective and there is an audible smile on

her face while she is singing. Double tracking and varispeeding disguise

Jason's rather lesser voice, but they drift agreeably enough through the song,

constructed as only “professionals” could construct it (twenty years previously

it might have been a hit for Jackie Trent and Tony Hatch, authors of the Neighbours theme tune) with that

question mark of an augmented minor underscoring the eighth bar of each chorus,

under "oh so true" as though questioning "how true is this,

really?” After all, “all the love I have is especially

for you” – what exactly does that mean? That it’s also distributed in lesser

quantities elsewhere?

Perhaps you had to watch the soap at the time to understand

the phenomenon fully, although I believe that Angry Anderson’s “Suddenly,” the

ballad which soundtracked the actual wedding scene, is far more upfront and

heartfelt in both intent and delivery, and other singing actors approached the

secondary art with far more adventure and enterprise – David Essex, for

example, was fully the equal of Kevin Coyne and Peter Hammill in the seventies,

David Cassidy’s voice cut through when needed – you believed him, and while Richard Harris admitted he was never the

world’s greatest singer, that worked to Jimmy Webb’s advantage enough to yield

two very fine albums. But other things in Australia were also ahead of this

jolly game; Midnight Oil’s Diesel And

Dust reminded us that there was more to that land than boy meets girl,

while Michael Hutchence’s Max Q

side-project was a considerably bolder take on electropop (imagine Donovan

having a go at “Way Of The World” or “Buckethead”).

The trouble with Ten

Good Reasons – well, one of them, anyway – lies, I think, in the overall

presentation and especially the presence of “Sealed With A Kiss”; as with Kylie, here is a cover of a pre-Beatles

pop song, and one is left with the impression that, given the singers were

brought into the studio, did their vocals double-quick under strict

supervision, and then emerged at the other end, what SAW wanted was a world

where rock ‘n’ roll had never happened; where popular music was a polite

procedural straight back to the days of 1953-4 with well-scrubbed, clean-minded

singers who never offended anybody but never stayed in anybody’s mind. No doubt

when faced with such a viewpoint, SAW would shrug their shoulders in genuine what’s-wrong-with-that?

Bafflement and furthermore say that their records were never for people like me

anyway. I wonder how many of the teenage girls who screamed at Jason and these

songs, and who are now in or approaching their forties, view this music now

other than with fond personal nostalgia.

It was a bit of an aesthetic quandary, but typically Lena

pointed out a comparison from left field which I had not even considered – and yes,

I have to be hard, up to a point, with SAW because once upon a time, and in not

dissimilar circumstances, there were…

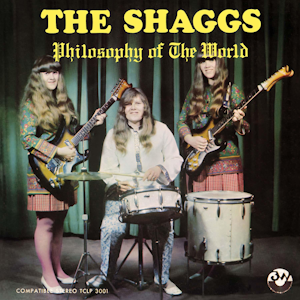

What we know about, and how we value, The Shaggs were down

to the stubborn perseverance of their father Austin Wiggin Jr. Taking one of his

mother’s palm readings as a prophecy, he took his daughters out of school,

bought them instruments and essentially pushed them into writing songs and

performing as a band. The girls were not sure that they were ready for making a

record, but their father was insistent; sure enough, twelve songs were taped and

the Philosophy Of The World album was

ready to run.

It may well be that pére

Wiggins was a tyrant with a temper. But he must have heard what few others,

including the group themselves, could hear. Listening to Philosophy is a little like listening to three musicians playing

three separate songs at the same time, or a jigsaw puzzle of a pop group whose

pieces are not quite in alignment. They sang of simple but resonant things, of

world love (the title song), the importance of parents (“Who Are Parents?”) and

God (“We Have A Savior”) and did it with such inconvertible honesty that

complaining that the drummer wasn’t quite doing what the two guitarists were

doing seemed petty.

This was the music of teenagers who weren’t allowed out of

the house to go to gigs, who were influenced purely by the pop they heard on

the radio – mainly Herman’s Hermits, Ricky Nelson and the Monkees. This worked

in their favour; if Philosophy had

been put together by some arthouse smart alecks, you would have seen right

through it on a first listen. But more importantly, what you hear is a group in

the throes of learning how to play together. Terry Adams’ Ornette comparisons

aren’t really fair (except that Coleman had his own unshakeable notion of

tonality and how to use it), although the late Helen Wiggin’s drumming, when

coaxed away from basic midtempo 4/4, occasionally rolls like the young Denardo,

for example on “My Pal Foot Foot.” Likewise, on songs such as “My Companion”

and “Things I Wonder,” Dorothy and Betty’s guitars shift regularly out of recognised

harmonic consonance. On “My Pal Foot Foot,” the three musicians even, if only

by accident, discover new ways of interacting.

Finally, the group slowly forms into something not yet quite

together, but approaching notions of coherence. “Why Do I Feel?,” the album’s

longest song, at just under four minutes, sees the musicians reaching some kind

of rapprochement; by the time we

reach “We Have A Savior,” they are playing as an almost recognisable group.

Crucially, these unforgiving hothouse conditions gave the Wiggin sisters a

chance to show the world what they were really like, lets us witness the

formation of something from what might initially seem like nothing. Whereas

with Ten Good Reasons, the system

appears to have been: get it clean and get it right and anyone can come in and

do what they like on top, as long as it’s what we like. I’m not sure that’s what

music was, or is, meant to be about.