(#204: 10 February 1979, 1 week)

Track listing: Rat Trap (Boomtown Rats)/Hanging On The Telephone (Blondie)/Giving Up, Giving In (Three Degrees)/I Love America (Patrick Juvet)/I Lost My Heart To A Starship Trooper (Hot Gossip)/Supernature (Cerrone)/Love Don’t Live Here Anymore (Rose Royce)/I’ll Put You Together Again (Hot Chocolate)/Anyway You Do It (Liquid Gold)/Y.M.C.A. (Village People)/Rasputin (Boney M)/Lay Your Love On Me (Racey)/Mexican Girl (Smokie)/Don’t Let It Fade Away (Darts)/Radio, Radio (Elvis Costello)/Drummer Man (Tonight)/Hot Child In The City (Nick Gilder)/Come Back Jonee (Devo)/Toast (Streetband)/Stumblin’ In (Suzi Quatro/Chris Norman)

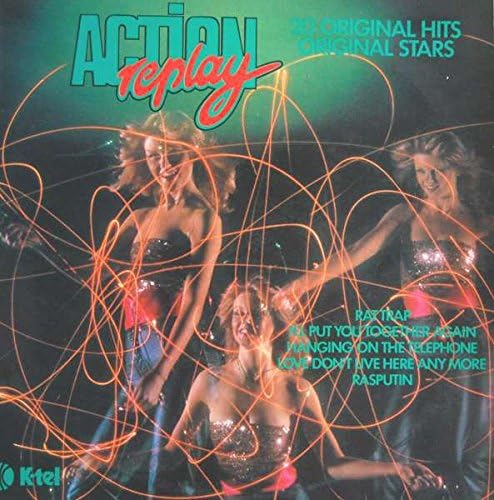

It was nearing the end of the seventies, and K-Tel were determined to appear modern; hence the actually rather disturbing cover of their latest grab-bag of recent hits and near-hits concealing the same old proviso about track running times being altered, etc., which in practice means that “Love Don’t Live Here Anymore” and “Y.M.C.A.” are cruelly bisected while turgid dirges like “Rat Trap” and “I’ll Put You Together Again” groan on forever (the latter, though sung with evident heart by Errol Brown, is not so much a late seventies forerunner of "Everybody Hurts" but more the song from the musical that it actually was; Dear Anyone, about a magazine agony column; hence the rather clunky references to pens and writing in Don Black's lyric). That having been said, it is a better, more coherent album than Don’t Walk – Boogie, a lot surer about what it wants to be, with a much better hits-to-misses ratio (two number ones, and only one track here missed the UK Top 75). It’s also the first number one album I’ve come across in some time which advertises another record on its cover, namely New Dimensions by the Three Degrees, which is certainly more than worth getting but strange to find publicised here.

Analytically it can be broken down into the following components:

New Wave

The Boomtown Rats ended Disco Fever and begin this one; “Rat Trap” is documented as being the first “official” “New Wave” number one single, although its connections with any kind of wave, new or otherwise, are indistinct. Actually it starts out as a Thin Lizzy wannabe, with characteristically whispered/grumbled Lynott-esque vocals, before setting out to become a Barrytown version of Springsteen’s “Jungleland,” and plods on with lots of undirected anger. Yes, Billy and Judy, it’s a shithole and you’ve gotta get out of this place; now tell me something I didn’t already know.

“Hanging On The Telephone” does so much better, by setting its sights a lot lower; the music’s careful rush reveals that Blondie knew their Nuggets backwards and forwards, while Debbie Harry’s growls, purrs and cries of sexual frustration give a lot more punch to the song’s subject matter than some of the male contributors to this record. Supreme stuff, with a pointed and focused production by Mike Chapman, of whom more later.

Disco

The USA invented disco, but Europe picked up the ball and ran with it; the Three Degrees, needing a hit, hooked up with Giorgio Moroder and produced the brilliant “Giving Up, Giving In,” with its endless circulatory Roland patterns, aggrieved syndrum punches and a show-stoppingly angry lead vocal from Sheila Ferguson (“You can sweet talk to the wind”). Best heard in the context of the sequenced/segued first side of the aforementioned New Dimensions, but the song could have been written and produced this week and would have made a far better “comeback” single for Girls Aloud than the trying-far-too-hard “Something New.”

Europe kept hold of the ball; Jacques Morali was involved with both “I Love America” and “Y.M.C.A.” and both songs see America as a metaphor for the future; Patrick Juvet is Swiss and sings with a high-pitched but happy sense of bewilderment as though America will give him more than what he wants (though again readers are directed to the full fourteen-minute 12” with its multi-genre tributes). Village People lead singer and “Y.M.C.A.” co-writer Victor Willis always believed that the song was a signifier for the land of freedom, and in great part the song works so well because he sings it absolutely straight. He believes in what the song promises, and if there are any subtexts beyond that, it will be a surprise but also a bonus. “Ra-Ra-Rasputin” has already been dealt with, but Cerrone’s “Supernature” again demonstrates how Europe, and in particular Italy, were running back – a very 1968 lyric, this, about science and strange creatures, not to mention the central “Days Of Pearly Spencer” riff – to take a forward leap. Both Lena and I will have more to say about “Love Don’t Live Here Anymore” but for now it’s sufficient to think of the synth bass introduction as a midway bridge between “Ball Of Confusion” and “State Of Independence.”

UK Disco

Outside the developing realms of Britfunk, UK disco was lagging a little behind. “Anyway You Do It” was Liquid Gold’s first hit (and their last one until “Dance Yourself Dizzy” well over a year later); featuring singer Ellie Hope and co-written and produced by future Beach Boy Adrian Baker, it huffs and puffs where it should glide, and sounds like a Mad Lizzie exercise workout routine.

“Supernature” made our top ten mainly as a result of being used as the theme tune to The Kenny Everett Video Show, hence its placement here next to Hot Gossip, the dance troupe which allegedly went where Legs and Co. would not dare. If anything, both troupes now look strictly of their time and not remotely sexy (nor did either get me excited at the time), and “Starship Trooper,” famously featuring a young Sarah Brightman on lead vocal – you won’t recognise her by the time we get back to her – is really a very corny affair, with its single entendres, endless musical quotes, “Captain Strange”s and “droid”s; somewhat pallid when set next to “Stardance” or Dee D Jackson’s chillingly icy “Automatic Lover.”

Doo Wop Revivalism

“Don’t Let It Fade Away” was a slightly atypical record by Darts, the Showaddywaddy it was hip to like, but as would-be epic ballads go it’s not a bad effort, like a slightly less dramatic “Don’t Let The Sun Go Down On Me” crossed with a politer “Let It Be.”

Power Pop

Do you remember the very brief UK power pop revival in early 1978? Already people were looking for a way out of punk, and the prime movers here were a besuited group called The Pleasers, who received much music press coverage and expressed the wish that their debut single, a hopeful stab at the Who’s “The Kids Are Alright,” made #17 in the charts, since that was where “Love Me Do” had peaked. And you thought that record collection rock began in the nineties.

The Pleasers came to nothing, but Southend group Tonight sprung seemingly out of nowhere onto Top Of The Pops in early 1978 with the excitable and slightly overlong “Drummer Man” (Action Replay must be the only number one album to contain songs with words like “anaesthetise” and “majorette” in their lyrics) before, essentially, disappearing back into nowhere (one more minor hit single and an album that was recorded but I’m not sure was ever released). The Knack did this sort of thing so much better.

Post Modern

Akron’s Devo were heroes in my third year at school. I first heard the single version of “Jocko Homo” on, of all places, Alan Freeman’s Saturday Rock Show and was immediately hooked, buying both that and their follow-up cover of “Satisfaction.” “Come Back Jonee,” from their debut album, sees them moving steadily into a pop mainstream of sorts but still sounds bloody and admirably strange, like a Talking Heads cover of “Johnny B Goode” cut up and reassembled in not quite the same order. In the undergrowth, producer Brian Eno works patiently on his strategies for eighties pop.

On which subject, good morning to you, Paul Young, improvising (though there’s a composer credit) his way through some meditations on the nature and appeal of toast with a group which would shortly afterwards into the Q-Tips. With scraping knives, whistling kettles, off-handed scat singing and a lyric more disturbing than it might initially appear – is he really making toast at the age of three or four months? – it’s a wonder that this got anywhere near, let alone into, the Top 20; it is also, by some distance, the best thing Young ever did. But more of him anon.

Old Men, Get Out Of Those Young Girls’ Lives

Oh dear. The mirthlessly mirthful Racey, for those confused heads nostalgic for the days of Mud and the Rubettes, pounding their way through Z-grade Chinnichap (more Chinni than Chap, I’d say) bubblegum. “When I met you, you were seventeen/Not just another teenage queen.” It doesn’t say how old the singer is, and it is, like Racey and mainstream British seventies pop itself, rather creepy.

Everyone’s favourite post-punk pioneers Smokie roll up for a group composition “Mexican Girl” which is as good as you’d expect a Smokie group composition to be, i.e. lots of “sensitive” Spanish guitar and castanets (together with a throwaway “Then I Kissed Her” reference), a heart that’s “as big as a stone,” a singer who doesn’t know what “hasta la vista” means and another highly questionable lyric in general (“She looked so fine/Well, she was alright”). A shame, since Chris Norman does much better on the Suzi duet “Stumblin’ In,” mainly because Chinn and Chapman go for straight AoR and pretty much hit the target (it was a million-seller everywhere except in Britain).

Nick Gilder was born in London but raised in Vancouver; he was in the rock band Sweeney Todd with a very young Bryan Adams, and “Hot Child In The City,” despite doing nothing in Britain, was a US number one. Musically it does look forward to eighties Recklessness – it’s like a slowed-down Cars – but the subject matter of teenage child prostitution, where Gilder alternately addresses the object of his affections as “child,” “woman” and “child” before concluding “We’ll make love,” is not one you could get away with these days, and I don’t know that it should have been allowed to be gotten away with in those days. It leaves the same distaste in the listener’s mouth as things like “Young Girl” and one wonders where, if anywhere, it stops.

The Payoff

“Radio, Radio,” presented here in its full, unedited form, seems to be the point that this record might be trying to make. Costello had released one album full of slightly bitter love songs backed by musicians who would one day more or less back Huey Lewis, and then came the Attractions and Nick Lowe and a second album of friable anger that spoke directly to every decent, resentful geek ignored in the classroom or passed over at work. “Radio, Radio” emerged as a stand-alone single in late 1978 and was quickly adopted by radio stations blindly assuming that any song with the word “radio” in its title was worth playing to infinity.

An extremely blind assumption here, since Costello is attacking the very nature of British radio; the Attractions have rarely sounded more febrile, while the singer barks about a broken old radio switch and having to sit through late night ‘phone-ins and Top 40 carousels which present a nightmare inverse vision of the Britain he thinks he knows and which, he also thinks, may be slowly summoning up its rearguard forces to obliterate him. The closing citation of Richman’s “Roadrunner” is lethally ironic, and the suggestion is that not just that British radio, but the whole of British culture and society, has been built on a false and crooked premise. It is frightening and compelling, and helps lead us further into a year where society is not going to be quite as docile or acquiescent as one might think – although many of the upcoming number ones appear to suggest that a silent majority liked oppression and an early bed more than they might pretend to express.