Wednesday, 31 October 2012

Leo SAYER: The Very Best Of Leo Sayer

(#208: 28 April 1979, 3 weeks)

Track listing: When I Need You/You Make Me Feel Like Dancing/Raining In My Heart/How Much Love/Dancing The Night Away/Thunder In My Heart/I Can’t Stop Loving You (Though I Try)/One Man Band/Giving It All Away/Train/Let It Be/Long Tall Glasses/Moonlighting/The Show Must Go On

Look at him dancing! He’s dancing on the ceiling, admittedly, but he has only good intentions. Wacky Leo Sayer, always amiable, never taking himself too seriously, the seventies’ very own Olly Murs. At least that’s the impression he’s strived to convey over the years, but at his centre is a quiet and unshakable sense of dignity. I remember a BBC2 series from a dozen or so years ago called Celebrities where various stars – not so much relegated from the Celebrity Premier League as never having got out of the Championship (Bernie Clifton, Keith Harris) – were seen going about their daily celebrity duties. Among them was Leo Sayer, his hits long and far behind him, but he remained irrepressible, whether looking for a new girlfriend (without much success) or flitting about between Britain and the West Coast, reminiscing about how he was in the same room, and indeed at the same piano, as Albert Hammond when he put together the music to “When I Need You”; despite his physical smallness, he still seemed too big for the programme, and before long he became lovable again.

But superficial appearances can be deceptive; his subsequent appearance on Celebrity Big Brother suggested that beneath the jokey surface lay a bit of a temper, and likewise the fourteen songs collected here are not quite the genial, face-licking pop they might initially seem to represent. The album is well designed; one side of his chartbusting American work with Richard Perry, and another side of the things he did in Britain with Dave Courtney and Adam Faith before becoming famous elsewhere, with the “approachable” side coming first. But unlike other Atlantic-crossing rock stars one could mention, Sayer seems to have managed the transition well, mostly by setting his sights lower and also by maintaining his own personality amidst the gloss (four of the seven songs on side one, and six of the seven songs on side two, were co-written by him).

I am not sure, however, that the move and success got rid of the trouble that was, and perhaps still is, an integral part of him. Some of these recordings feature some of the most intense and aggressive singing I’ve heard on a number one album; from the start, it was clear that Sayer had a bee in his bonnet, and was desperate to avoid being stung.

Born in Shoreham-on-Sea, Sussex, he worked the standard late sixties/early seventies Brit singer-songwriter route, scuffling about in clubs, busking, etc., until his work came to the attention of songwriter and record producer Courtney, who in turn persuaded Adam Faith to manage and co-produce him (at the time of this album’s release, Faith was still, with Colin Berlin, Sayer’s manager). Most people first heard of him via Roger Daltrey’s 1973 hit version of his “Giving It All Away” and he was soon signed up by Chrysalis and released an album, Silverbird later the same year. It is a typically murky, pessimistic set of songs, preoccupied with façades and masquerades, its best track being the agonised closer “Isn’t Anybody Going Home?,” one of the best of the late period let’s-get-out-of-the-sixties British pop tunes.

From the same album came his first hit single, “The Show Must Go On,” which he performed on television dressed in full pierrot clown make-up and costume, with bulging eyes and mouth beneath; from memory, he looked rather like Adam Ant. Falling just short of becoming the 1973 Christmas number one single, it is a remarkably intense performance, even for its time, with Sayer displaying the whole of his vocal gamut, from babyish falsetto via gutsy scat-singing to stinging punk growl, singing a song Scott Walker would have understood, about being ripped off and abused, about wanting to destroy the theatre where the audience are all after his blood, and issuing a determined “NO!” to the song’s ironic title (Sayer was extremely, and rightly, displeased when Three Dog Night covered the song the following year and changed the tag from “I won’t let the show go on” to “I must let the show go on,” thereby missing the song’s entire point).

Having gotten that out of his system, Sayer took off the make-up and settled down to become an apparently likeable and idiosyncratic storyteller. His second album, 1974’s Just A Boy, is here represented by no less than four tracks, two of which were top ten singles; “One Man Band” was an autobiographical jug-band canter (he really was sent flying by a taxi in Ladbroke Grove; and note how in the first chorus the clarinet plays Philip Glass arpeggios) which still conceals a roar of “Nobody knows nor understands!”; “Long Tall Glasses” is a shaggy dog story which Sayer starts out singing like Dylan (or, more accurately, Loudon Wainwright III) – hang on, being told you have to dance before you can eat; is this Shoreditch in 2012? – until, when he finds out to his astonishment and delight that he can dance, he turns the song into a serrated Noddy Holder bark (“Look at me dance on the FLOOOOOOOOOR MOVIN’!”). Throughout the song remains unmistakably British, with its references to “poultry and game” and Victor Silvester.

Then there is his own reading of “Giving It All Away” which pretty much sends Daltrey’s back to the pavilion; Sayer is a lyrics man, and so can deliver his thoughts without being handicapped by the necessity to be “Roger Daltrey.” Lyrically not at all far from “The Show Must Go On,” again he finds that he has been cheated, taken for granted, but the arrangement here – starting off with just piano and organ, before gradually building up to a full orchestra (with no drums) – is far more sympathetic, and Sayer’s rage is plainly palpable (“Oh! I! KNOW! BETTERNOW!!” he cries as though about to slit his wrist with a blunt potato peeler; his repeated “just a boy”s are watery in their grief). The final selection, “Train,” sums up Sayer’s approach in general; alternating between slow solo verses and fast group choruses, he admits that it is probably his fate to go away, and come back, again and again; once more we find the setting of wanting something being more enticing than actually getting it.

1975’s Another Year didn’t do quite as well, although its single “Moonlighting” gave him another number two hit single. It’s a reasonably well-constructed story song whose natural charm conceals some implausibilities (although it was supposedly based on a true story); if the lovers are old enough to work and be able to drive, why do they need to elope? Also of note here is Sayer’s tendency to cram conversational lyrics into a line, regardless of bar lines or scansion, and the increasing awareness that songs about printing works, M6 turn-offs, building societies, Montague Street, respraying vans and council offices were perhaps not going to get him a more international audience. The last song here is his take on “Let It Be” from Lou Reizner’s ill-fated All This And World War II project; he does the song good service, makes it less churchy and more singable, although I would have preferred his aggrieved reading of “I Am The Walrus” (“You let cha knick-ahs DAAAAAHHHHHHHNNNNNN!!”).

Then came the transition to the States, and his moment of world glory, but without losing anything of the Sayer-ness that had endeared him to British audiences. “You Make Me Feel Like Dancing” was the breakthrough smash - Billboard number one, yet another UK number two – and although it now sounds almost comically slow-paced, it did the required business, Sayer adapting modifying his “Long Tall Glasses” persona without, seemingly, any effort: his five descending, perfectly timed “no”s at the end of “I ain’t feeling tired,” his “flo-ho-hoar!” in the line “I can’t get off of the floor!” With Sayer and Barry Gibb I suppose it’s a case of chicken and egg as to who influenced whom, but if Sayer sounds like anyone here it’s more Little Jimmy Scott; a faultlessly controlled and frequently feminine-like falsetto.

“When I Need You,” his second US number one and – finally – his first UK chart-topper, is a good ballad sung in an evidently heartfelt technical and emotional tone. It’s another of those seventies songs about the musician’s lonely life on the road, but Sayer’s obvious craving is balanced out by his incurable optimism. The song and arrangement lope along in a patient manner akin to lovers’ rock, and I note how the multitracked Sayers on the staccato “It’s cold out! So hold out!” break are reminiscent of Jon Anderson.

It could be said that Sayer prospered in the States of 1977 because he filled a gap, performing (and largely co-writing) the sort of songs that Elton John was no longer prepared or willing to do. “How Much Love,” co-written by Sayer with Barry Mann, certainly owes something to “Philadelphia Freedom” (especially the string arrangement), but if “Giving It All Away” was the earlier angst-ridden Elton blown up to dangerous proportions, then Sayer, like Martin Fry after him, is only using “disco” as a tool, a mechanism to help him express something, in this case sexual indecision (“Should I come on strong or do I hesitate?”). Despite keeping his countenance throughout most of the song, Sayer finally loses control at fadeout and becomes despairing (“I! Can’t! Help! My! Self! Oh-whoah!”) as if, more than anything, he will lose love rather than consolidate it.

As for “Thunder In My Heart,” this contains the most impassioned, verging on hysterical, vocal I can think of in recent TPL times, possibly including John Lydon; as with the latter in the second half of “Holidays In The Sun” (which was out at more or less the same time), Sayer crams as many inchoate emotions into each line and stanza as he can; having arrived, he is (pace “How Much Love”) now unsure where to go or how to keep love (“Am I in too deep or should I swim to the shore?”). Against the beats and strings, he rants, gibbers, screams as effectively as any British male singer this side of Barry Ryan; it is one of his most naked performances, and one I knew immediately would eventually make number one, in whatever shape. It is almost too big for pop.

After “Thunder,” there was maybe nowhere to go except down, and so the remaining three songs here are tinged with deep melancholy. Sayer does Holly’s “Raining In My Heart” as a measured country-rock ballad, complete with his own harmonica. “Dancing The Night Away,” only ever an album track in Britain, is, though not written by Sayer, a fairly pitiless exercise in self-examination, which instantly pulls it away from “You Wear It Well” wannabe status; he is looking out over the Pacific, and the shoreline, but he’s empty inside because, well, the girl he asked to be patient in “When I Need You” wasn’t, and left him, He thinks about the past; the music goes up a heartbreakingly brief semitone on the line “The dresses you used to wear.” A violin solo materialises to remind us, again, of Mr Stewart. He admits he has painted himself into a corner (“I should look for companionship/But it just gets in my way”) and that, finally, after two big hits about dancing, he looks at people dancing on the beach, in the club, “But I just don’t dance no more.” He tries to visualise his ex-lover dancing, does his damnedest to bring back the memories, but now his instructions to her, “Ohhhh baby let me see you da-a-ance,” find him close to tears.

And at the end of that side one, we find “I Can’t Stop Loving You (Though I Try),” another ballad, another break-up song; he’s seeing her off at the train station, not a word is spoken in the taxi on the way there, she gives him her “goodbye smile” but nothing else, and he watches the train pull away knowing that this time he can’t drag it back. He doesn’t want to stay there, in the past, but can’t help himself; the song was written by Billy Nicholls, whose 1967 album Would You Believe? helped in its way to set the ground for artists like Sayer, and this is where we leave the man; back where he was at the beginning, having learned a few things, but perhaps destined, or doomed, to slide between the two paths for the rest of his days. Little wonder he eventually emigrated to Sydney and took Australian citizenship, so that he can dance as much as he likes without worrying whether or not anybody is watching him.

Sunday, 28 October 2012

Barbra STREISAND: Barbra Streisand's Greatest Hits Volume 2

(#207: 31 March 1979, 4 weeks)

Track listing: Love Theme From “A Star Is Born” (Evergreen)/Love Theme From “Eyes Of Laura Mars” (Prisoner)/My Heart Belongs To Me/Songbird/You Don’t Bring Me Flowers (Duet with Neil Diamond)/The Way We Were (From The Columbia Picture, Rastar Production, “The Way We Were”)/Sweet Inspiration-Where You Lead/All In Love Is Fair/Superman/Stoney End

There had been a first volume, in the spring of 1970, but that only made #44 on our charts, mainly because at that time Streisand was chiefly known here as a film actress and had only had one British hit to speak of (“Second Hand Rose”). In the States, Billboard never placed it higher than #32 but over the years it sold steadily enough to go double platinum. It is a shame I won’t be able to do it here since it denies me my only opportunity to talk about my favourite Streisand record, “Sam, You Made The Pants Too Long.” Even a little levity would not have gone amiss at the opposite end of the decade, on Volume 2.

Whereas the cover of the original Barbra Streisand’s Greatest Hits is autumnly colourful, Francesco Scavullo’s monochrome shot on the front of Volume 2 eclipses Streisand’s face – either smugly omnipotent or perilously worried – almost entirely. Once her hair was long and flowing; if you squinted enough you might think of her as the good sister to her contemporary Janis Joplin. Now it is permed and tied in a bow; it is uncertain whether she is a missing link between Claudius’ aunt Livia and Emeli Sandé. And the rear cover lists the tracks in the manner of an upmarket restaurant menu (I transcribed the track listing exactly as it reads).

What did the seventies do for, or to, Streisand? Here is somebody at home with, indeed brought up on, show tunes and jazz, but compelled to grow up and perform in the age of rock. So the formalist design of Volume 2 presents itself as if to say: well, look how far I’ve come, in those years, from The Owl And The Pussycat to The Main Event. Looked at that way, it might seem like no journey at all. But almost all of this record presents Streisand as a tasteful balladeer; only three of its ten tracks would sound out of place on The David Jacobs Collection, and one of these, the earliest, a plea for suicide, nurturing and Biblical apocalypse dressed as an upbeat Brill Building pop tune, is stuck right at the end of the record, almost as a gesture of defiance; this is how I began, now you know why I don’t want to go back there. But ego and insecurity, those closely-knit twins, have always been this singer’s twin motivational motors.

The album isn’t sequenced chronologically, and it’s noticeable that in Britain only four of its tracks made any commercial headway as singles (in the USA, conversely, eight of the tracks were at least Top 40 hits, and three of them went all the way; this record was a transatlantic chart-topper, in the States going quintuple platinum). This might suggest our differing attitude to what does or not constitute pop music, or raise the question of how far Streisand really reached, or attempted to reach, into pop. I don’t think she really understands Stevie Wonder or Carole King any more than, say, Gracie Fields might have done; that she tries to understand them is undeniable, but…

…this is a story of the seventies, that Me of Decades, and my central problem with Streisand, here as elsewhere, is the “me”-ness of her approach. “My heart belongs to ME,” “Where is my songbird who sings his songs for ME?,” “I am Superman.” I am not saying that this record should have been subtitled The World Should Revolve Around Me but that is the feeling that I get; in the live medley of “Sweet Inspiration/Where You Lead” she goads the audience along like a stern Brownies’ mistress, as if they are being made to clap their hands by force. Look, she says, I am too BIG for pop, maybe for the world, and everything should be remade in my image because…the dreaded “because” she doesn’t want to think about…because otherwise I’d be nothing; look how many of these songs find her without love, or wanting to fall out of love (with someone other than herself), or, in one instance, seeing love as a prison, always with the underlying fear that if she or the world gets it wrong, then it’s back to turning tricks on Boogie Street in Brooklyn, for dimes.

“Evergreen” is, mercifully, the only thing retained from A Star Is Born; as I previously said, this works because Streisand not only writes the music, but also keeps her performance relatively restrained, such that when her high notes break through, you can for once actually feel for her rather than feeling battered down by her Streisand-ness (I note that the song shares the same root chord – G major - and tempo as Gordon Lightfoot’s “If I Could Read Your Mind”).

But in no way could “Prisoner,” from that delightful romantic comedy The Eyes Of Laura Mars, be described as a “Love Theme,” as though Streisand were being sat on by Barry White. “You want to keep me here forever, I can’t escape” she shrieks as rock guitars and hammering drums close in around her; Lena’s friend, the writer Gemma Files, thought this practically a Nine Inch Nails song, and it’s true – one can easily envisage Trent Reznor gnashing his way through the song, whose rhythmic, melodic and lyrical constructs are all readily compatible with his own. Actually Streisand’s performance makes me wish that someone with a surer ability to take the song by the scruff of its neck and give it a really good shake – Tina Turner, maybe, or even Celine Dion (whose voice Streisand eerily presages here) – had covered it. It’s significant that Streisand turned down the lead role in the film itself (the one eventually taken by Faye Dunaway) because she regarded John Carpenter’s screenplay as too “kinky,” and despite earnest performances from Dunaway, Tommy Lee Jones and Brad Dourif the film really isn’t as good as some might remember it; I acknowledge its attempts to get behind the indivisible screen between fantasy and reality, between wishing and fulfilment, that is built up by a motion picture, but director Irvin Kershner wasn’t Hitchcock, and so the film turned out as a rather silly horror-crime affair, a long way from Rear Window.

After that, it’s back to ballads of snoozy egotism; “My Heart Belongs To Me” might usefully stand as an answer song to Elton’s “Sorry Seems To Be The Hardest Word” if, say, Kiki Dee had sung it, but with Barbra it’s another instance (like “Prisoner”) of love being, if anything, an inconvenience to her, like an old unpaid laundry bill. “Songbird” – not the Christine McVie tune – finds her even altering the lyric, from “the song” to “my song,” and wondering why she’s “all alone.” At the end, however, she does a little sequence of onomatopoeic slo-mo scat singing which, for a second, makes you realise how close her style is, in places, to that of Whitney Houston.

And then there’s the Superstar Team-Up, and Neil Diamond isn’t the only one wondering what the hell he’s doing here in the first place. “You Don’t Bring Me Flowers” in fact has a chequered history; co-writers Alan and Marilyn Bergman wrote a précis of the song for a TV show called All That Glitters. The song was not used, however, and was eventually rescued from disuse by Diamond, who worked on the music and expanded the to a usable length. He recorded it, alone, on his 1977 album I’m Glad You’re Here With Me Tonight; shortly afterwards, Streisand did a version for her Songbird album. In Louisville, Kentucky, WAKY-AM DJ Gary Guthrie noticed that both versions had been recorded in the same key, and so did what would now be called a “bootleg mix,” splicing the two readings together, apparently as a (rather sour-sounding) departure gift to his wife, whom he had just divorced. He played it on his show and demand went nationwide then through the roof, such that Diamond and Streisand were called upon to return to the studio and record a proper duet version of the song.

As a song it plays like Revolutionary Road set to music; a baby boomer hangover sequel to “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin’,” the dying embers of two people who have gradually realised they have nothing in common with each other. You would have thought it, wouldn’t you – these two Jewish kids from New York, of roughly the same age and with very similar upbringings, but who took very different paths. Hence Diamond’s is the rougher “pop” voice and Streisand’s the smoother “Broadway” voice, and listening to them is like hearing two people on separate planets, both thinking to themselves but out loud; she says this (with a “turn out the light” that sounds as though she wants and expects the world to end) and then he says that, and neither is ever going to agree. The plan was for a film of the song to be made but I’m glad they didn’t; for the unexpected but entirely logical sequel, see the Streisand/Donna Summer duet which at this point is still some six months down the road. Best to view this as a benchmark case of how two different forms of popular music cannot really communicate with each other.

Turning over to the second side of what could be called Barbra Streisand As Beverly Moss Might Know Her, there is “The Way We Were,” its pictures as scattered as the “used to be”s in “Flowers” but without even the promise of a broom to sweep them away. It is a movie title song not entirely unaware of its own absence of point (“Can it be that it was all so simple then?”) and because it is essentially a show tune, Streisand is more comfortable doing it; what I am not comfortable about is the central absurdity of the film that the song comes from, namely: what would somebody as bristling, fired-up and full of life and determination as Katie Morosky be doing wasting even a second of her time, let alone several decades of it, with a smug jerk like Hubbell Gardiner (even that name, Hubbell Gardiner; it sounds like the lead part in a very minor Peter Sellers knockabout comedy)? Isn’t someone as full of self-love as Robert Redford (who insisted that the novel’s writer Arthur Laurents fill out his character more for the screenplay) always going to end up taking the safe, easy, sellout option – but isn’t that what Redford does anyway, time and time again, including when he is supposed to be an English pilot (Out Of Africa) or a bored billionaire playboy (Indecent Exposure) or a horse whisperer (The Horse Whisperer)? There he is, always appearing on screen with that golden buttery sunrise glow behind him and that sickly toothy grin in front of him, like a cross between Tommy Steele and Dick van Dyke. I couldn’t imagine someone like Streisand falling for him or his schtick for an instant…

..and yet, “We simply choose to forget”? Do people really do that, Barbra? Is this Gil Scott-Heron’s “selective amnesia” again, or an inability to grasp with the song’s wider implications? It should be noted that the big hit version of the song in Britain was not recorded by Streisand, but by Gladys Knight; done before an audience, she can invest that line with several centuries of hurtful history, as well as (as she cleverly does in her extended spoken intro) tie its concerns to those of the Western world of the mid-seventies. Streisand only knows how to sing the song, rather than think it.

The endless live medley demonstrates further evidence that Streisand was never going to be Soul Sister Number 5001, let alone Number 1. The Carole King/Toni Stern song “Where You Lead” she had already recorded as a standalone single, but this came out as a merger with Dan Penn and Spooner Oldham’s “Sweet Inspiration”; starting out as another swirling, free-tempo ballad, she suddenly realises – several years before it was released – that this album seriously needs waking up, and hence six or so minutes of happy-clappy bat mitzvah gospel wa-heying. Possibly the sequence’s most embarrassing moment comes when she tries to impersonate Robert Plant: “The way you call me baby, BAY-BAYYYYEEE!!” It’s hard to think of her being in the same asteroid belt as Aretha – although both were born in the same year – and so it fails as a moment of would-be soul transcendence, not that that would have been of much concern to the doubtless expensively bowtied and tiara’d audience.

As if to prove that the planets of soul and Streisand would never meet, her “All In Love Is Fair” is a calamitous misreading; as done by the man who wrote it (Stevie Wonder) it’s one of my favourites of his, but Streisand cannot hope to nail it or even understand what is so underhandedly poignant about the song. Crucially, she fluffs on the key line – “The writer takes his pen” – and never recovers from that. It is as if the function of internal monologue or one-to-one conversation is lost on her irretrievably theatrical mind; not feeling the need to interpret the songs of others, so that they have some sort of relevance to her own life and state of being, she instead acts the songs, in the end always singing to the kid at the top of the gallery, keeping both diction and volume as clear as possible so that everyone in the audience hears her. But “All In Love Is Fair” is a grievous whisper of a song that daren’t even raise its voice; thus her final, extended “faaaaaaaaaaaaaaaair” misses irony and lament in favour of the trademark, unheard “big finish.” Look how big my finish is!

“Superman” is no better – look, Barbra, do you want love or not? Her coy Superman T-shirt on the album cover in question lends no clues (but note that she sings “SuperMAN” and not “SuperWOMAN”) - but her “Stoney End” is the biggest miss of all; I’m sure Laura Nyro enjoyed the royalty cheques, but Streisand has no idea how to identify with or inhabit the body of this song; a craving for mother and life to begin again which in its original form is comparable with (and arguably outdoes) primal scream therapied-Lennon is tossed off like the Good Book of Jesus of which you cannot imagine Streisand having read even a paragraph. There are some dreadful misses (“cradle me again” is supposed to go up, not down), an overacted “ragin’ so-ooooOOOOOOUUUUUL!” squeak, and a final cry for “Mama” which has all the poignancy of Violet Elizabeth Bott demanding more pocket money. It is embarrassing how far the backing singers and musicians outclass her. What did the seventies do for Streisand, then? From this evidence, I’d say that ego and insecurity fought an honourable draw, albeit in favour of a mostly misdirected talent. As with Spirits Having Flown, there is much too much soporific, self-pitying sentimentality at work (or not at work) here; whether each form would enhance the other, or cancel each other out, we will investigate in 1980.

Wednesday, 24 October 2012

The BEE GEES: Spirits Having Flown

(#206: 17 March 1979, 2 weeks)

Track listing: Tragedy/Too Much Heaven/Love You Inside Out/Reaching Out/Spirits (Having Flown)/Search, Find/Stop (Think Again)/Living Together/I’m Satisfied/Until

I remember that it was the Melody Maker letters page, sometime in 1979, and somebody had written in about opening a bottle of wine and settling down with his wife to enjoy the new Bee Gees album. It was only a short letter and I think he had some sort of humorous point to make, about the vocals or the lyrics; I can’t really recall the rest of it, other than in 1979 the new Bee Gees album was something you sat down, opened a bottle of wine and listened to, in good, familial (?) company.

The Bee Gees have always been my mother’s favourite group, and my father didn’t mind them too much either. I’m not sure why my mother should love them so much, except they were tuneful and somewhere in their voices and hearts, “meant it.” That having been said, I did not grow up in a household full of Bee Gees records (other than the ones I myself bought); in the communal record cabinet the only album of theirs that was present was the Saturday Night Fever soundtrack. That seemed to do; it was evidence that my parents were “modern” yet “tasteful,” as tasteful as that glass of the finest Chianti, straight out of the wine shop on Uddingston Main Street.

A new Bee Gees album, however, had suddenly become a major event; “everyone” was waiting for it – what have they got up their sleeves? What could possibly top SNF? – in the way I understand people in the past waited for the new Beatles record. In a 1978 which they completely dominated (and yet a year where they only managed a fortnight on top of the UK singles chart), there were some murmurs of disappointment when the trailer single “Too Much Heaven” was released; an attempt to redo “How Deep Is Your Love,” a mellow, tasteful ballad, not truly what anybody expected or wanted (and hence it “only” made #3 here; Grease suddenly seemed much more fun).

In early 1979, “Tragedy” was released as a single, however, and was much better received (giving them their fourth British number one), reigniting expectations; oh, this is much more up-to-date – will they even (mutters under snowy breath) make a New Wave album? I suppose it was always too much, and too unnatural a thing, to ask of them; but for a record which worldwide sold some 35 million copies and achieved Barry Gibb’s aim of getting the Bee Gees onto American black radio, the response still seemed rather muted, compared with Fever (only a fortnight at number one, you will note, set against SNF’s eighteen weeks); oh great, guys, an easy listening album. RSO were compelled to rush out a Greatest compilation before the end of the year to compensate (for “only” 35 million copies?); a lot of record shops complained about overstocks and returns.

The question now is how and where Spirits Having Flown stands in the chartered history of the Bee Gees, a history that can charitably be described as “strange”; one can admire the Gibbs’ steadfast stubbornness in not making a “disco album” and yet feel that, whatever else may have happened to them, this is the album the Bee Gees would have made and put out in 1979 anyway. Parallel Lines it is not, but is it an unexpected sequel to Odessa, ten years after?

I’m too young to remember at first hand how bizarre the initial impact of the Bee Gees, newly returned from Australia, must have come across, but the evidence is plentiful. In a lot of ways I think of them as an alternate universe Walker Brothers; a true familial group that wandered off from the Isle of Man and Manchester to Australia then sloped back “home” but had absorbed the Beatles and Otis Redding and goodness knows how many one-off English proto-psychedelic tinderboxes of whimsy rather than Spector, Jack Jones and Gershwin. Barry and Robin were not quite like Scott and John Walker; the division of labour and art was more equitable, and throughout their career both had plenty of opportunities to be both John and Scott (Maurice would have been the Gary Leeds figure, but he had rather more to offer; contributing directly to the songwriting process, he first played keyboards, then switched to bass, though returned to keyboards for live gigs in the group’s later stages). In addition, their view of the world and life could be as deliriously morbid as Scott’s, but although they had musical ambitions, they never broke out of their “pop” shell and seemed to have been pretty content to work within The System.

Still, what were they like in the later sixties, when there wasn’t really a “system”? Their calling card, the 1966 Australian number one “Spicks And Specks,” immediately gave notice that their teenage dream was not as others’; “Where is the sun?…It is dead,” they sing, deadpan, over an even more deadpan march rhythm (possibly influenced by the Yardbirds’ “Shapes Of Things”). When “New York Mining Disaster 1941” was launched (and it was actually their second British single; “Spicks And Specks” had been released, with little reaction), copies were sent to radio stations with a plain white label, blank except for the song title. Thinking this was an undercover new Beatles release, the record picked up airplay and made the Top 20, but the key elements of Bee Gees are already there; the doomed lover, prevented by force from reaching his true love, perhaps already fatalistic about dying alone.

Despite that and subsequent single releases, however, the first few Bee Gees albums demonstrate that they weren’t just about semi-worldly melancholic ballads. Bee Gees 1st is, if anything, the Gibbs doing Nuggets, full of fast-paced amphetamine garage pop together with more measured oddities (“Turn Of The Century”), “proper” soul balladry (“To Love Somebody,” which Otis would have recorded had he not got on the ‘plane; as it turned out, Nina Simone’s tortuous reading was the big British hit version, in early 1969) and “Every Christian Lion Hearted Man Will Show You,” a Mellotron-ed proto-space rock epic that should have shown the Moody Blues early doors. Clearly there was ambition here, but was it focused?

Horizontal, the first of two 1968 releases, again put strong ballads (“And The Sun Will Shine,” “With The Sun In My Eyes”) against a vision of England as amicably twisted as that of Scott’s (“Harry Braff,” “The Earnest Of Being George”). Idea could almost be the group’s Scott 3 (and I hope Walker watchers spotted the simple pun in that title) as, though not specifically set around a group of people living in the same conceptual place, still feels like a single soul viewed from a dozen different angles; the bedsit trauma of “Kilburn Towers” and simple poignancy of “When The Swallows Fly” balancing out the general WTF-ness of “Indian Gin And Whisky Dry” and “I’ve Decided To Join The Air Force.” The supremely fatalistic “I Started A Joke” – Robin as von Sydow’s knight in The Seventh Seal, accepting his fate for a greater good – pulls all the record’s grey strands together.

Then came Odessa, that iceberg of a double album from 1969 which temporarily finished the group off; so wide and varied are its canyons that for great parts of it the group disappears completely, returning with, variously, stoned country music, fragile deep soul laments, damn-you-England tantrums (“I Laugh In Your Face”), early electropop (aptly on the subject of Thomas Edison), orchestral surges and, as the Gibbs make their protracted exit, “First Of May” where they perhaps already know that one game is up.

There were arguments over Odessa, and single A and B sides, and Robin stormed off to go solo for awhile; 1969’s Robin’s Reign, done in part with Maurice’s help, sounds like Peter Noone crossing paths with Scott 4; a benighted, unfocused mind wondering what to make of anything (as the five-minute-plus closer “Most Of My Life” makes clear), was followed by 1970’s never-released Sing Slowly Sisters - I’m not sure whether the latter is Britain’s own Sister Lovers (Chilton used a band rather than Kenny Clayton’s probing orchestral arrangements) but it finds Robin falling further into himself and may well be the logistical go-no-further point of British “avant-MoR” (on the contemporaneous ’Til The Band Comes In, even Scott could go no further than “The War Is Over” before “coming home” to interpretations of the songs of others, but then I don’t think he really needs to; Barry Ryan, having shrieked his brains out on 1971’s “Red Man,” largely retreats to harmless German Europop for the rest of the seventies); songs like “Cold Be My Days” and “The Flag I Flew” were never going to be featured on Saturday night BBC1 light entertainment schedules (and the album still awaits a formal release; Robin’s Reign was available on CD in Germany for about five minutes in the early noughties. Whoever now holds the rights to these recordings in Robin’s estate would do well to look into giving his solo back catalogue the attention it deserves).

While Robin was away, Barry and Maurice starred in a strange television special (and equally strange soundtrack album) called Cucumber Castle, but after they persuaded Robin to rejoin the group, their best record from this period is probably 1971’s Trafalgar (compare Scott’s “The World’s Strongest Man” with Barry’s “The Greatest Man In The World”) with its US number one original of “How Can You Mend A Broken Heart?,” with its tremulous whispers and tubular bells as tearful a goodbye to the sixties (“And let me live again”) as “Bridge Over Troubled Water” (though their reading swiftly fell into the shadow of Al Green’s patient six-and-a-half-minute dissection of the song, a peerless performance vitalised by Al Jackson’s rhetorically deadpan drumming).

But the week that song went to number one on Billboard (having mysteriously not even been considered for single release in Britain), the group were midway through a residency at Batley Variety Club, and this was their trajectory for the next couple of years (like Scott’s); steadily declining chart positions, banishment to the pitiless working man’s club circuit, listless records in which maybe even the Bee Gees themselves didn’t believe (Life In A Tin Can; trust me, the title’s much more interesting than the record).

Eventually they packed up and moved to Miami, and Arif Mardin. Wishing to steer them gently into something resembling the present tense, his first production for them, 1974’s Mr Natural had no hits, and still demonstrated a struggle between what they once were and what they could still be (there are a couple of straight-out hard rock tracks on there, one of which is called, Lord help me, “Heavy Breathing”) but enough decent would-be R&B stuff (“Lost In Your Love,” the title track) to justify taking the experiment further.

1975’s Main Course saw them getting it right, with its three hit singles and a general sense of rebirth. The following year’s Children Of The World seemed a little rushed and forced (compared with, say, Boz Scaggs’ Silk Degrees - now there’s a record that should have been called Mr Natural) but still had “You Should Be Dancing,” “Love So Right” and other worthy songs.

Then came the weekend of songs that ended up on Saturday Night Fever (those four songs of Scott’s on Nite Flights!) and suddenly the Bee Gees were Kings of Pop, with all the potential for fatality that such a title might imply, and Inventors of Disco (erm…). They were told they could do anything and then unfortunately went ahead and did anything, specifically the movie of Sgt. Pepper which has been carefully pencilled out of history and after which Peter Frampton was lucky still to have a career. They were also busy writing and producing hits for their Tigerbeat kid brother Andy, as well as for other, less obvious names; their big buck superstar productions lay ahead in the eighties, but for now people like Yvonne Elliman, Samantha Sang and Teri de Sario would do.

All of this work, added to touring and so forth, makes it a miracle that they had time even to consider making an album of their own. The cover of Spirits Having Flown, however, looks as though they want to incinerate their past; there they are, blowing or being blown by an unseen wind towards the left, while underneath them is a big red blob of…what? Fire, consuming all that they used to be? On the back we see three shades of ghosts standing on rocks, their backs to the Atlantic, and did people once inhabit these shadows?

I came across a CD copy of the album in a charity shop and wondered at the record shop packaging; on the front is a yellow, red and black Virgin Megastore price sticker, and beneath it is one of those generic PolyGram “SPECIAL PRICE” stickers used to promote albums well past their commercial peak. The Virgin sticker had a date on it – 01/01/99, the first day of the last year of the millennium, and a day that I was lucky to live to see – along with a “SPECIAL PRICE” of £10.49. Given the CD’s minimal repackaging – I am not saying that somebody photocopied a copy of the LP original, but they might as well have done, complete with credits that you would have to hire a telescope from Jodrell Bank to read properly – I was not surprised that in the intervening years it had worked its way down to the £2.99 that I was actually charged. It did strike me, however, as a fitting metaphor for how this album seems to have become forgotten.

“Tragedy” opens the record and is a red herring, clearly an attempt to do Abba (with its numerous indirect references to “Knowing Me, Knowing You”), with Barry at his most desperate and forlorn. It is also the coda to which the rest of the album is something of an afterthought, dealing as the record does with lost love, or accidentally mislaid love – a very Scott-ish obsession with the transient moment and the impossible attempts to retrieve or replicate it. “Too Much Heaven” is, after “Be My Baby,” Brian Wilson’s favourite record, and you can see what would appeal to him; the touchless harmonies (like Rachamaninov’s Vespers at points: “Our precious love…”), the Wilson-esque homilies (“Loving’s such a beautiful thing”) – although I note the song’s rather closer relationship with “I’m Stone In Love With You,” complete with lush would-be Thom Bell orchestrations, and high Barry’s similarity to Russell Thompkins Jnr. (although he is a bit shriller and more strident than Thompkins).

Still, it’s a good Stylistics record, and the rest of side one plays in much the same fashion; a very decent MoR soul album with lots of only slightly dated slow jams. “Love You Inside Out” is, despite its Bee Gee World lyrical schemata, a song good and purposeful enough for Feist to cover and make sense of. In terms of soul balladry, Barry (this really is a Barry album above all else) does best on “Reaching Out”; his “forever…oh…” at the end of the first chorus, his “I’ll be reaching out…ahh!,” the careful harp accompaniment. The title track – only very belatedly released as a single in Britain, and then only to promote the Greatest compilation – is eighties yacht rock in waiting, very Florida Keys, a patient lapping of percussion and horns (including, on flute, Herbie Mann) which could undulate forever like the waves of the Atlantic. Set against this, though, are the forces of nature – “hurricane,” “fire,” “air,” “dawn,” “empty skies” – which lend the song’s central yearning a reality glimpsed beneath the façade of airless efficiency (best encapsulated on the other side of America in 1980, on Steely Dan’s “Glamour Profession,” wherein drug oblivion is pursued under music so perfectly set it could be played by machines; it is as deep a requiem for recent times as Joy Division’s “Decades” and its whiter-than-white (snow, sniff) air is precisely delineated by a wandering solo guitar, probably played by Steve Khan). Christopher Cross and the rest of the eighties await.

Side two doesn’t live up to these standards, however. That’s not to say that the five songs here are indolent or presumptuous, merely that the group sticks a lot of irons in the fire (to retrieve another Sing Slowly Sisters track title) and none of them really burns. “Search, Find” finally makes a tentative effort to go to the disco, but it’s a 1974 Philly disco (Teddy Pendergrass, perhaps, though the collective falsettos put one more in mind of the Three Degrees) with the horns mixed down so far and compressed so tightly that they sound like an accordion. “Stop (Think Again)” – hey, what’s with all these song titles as instructions; are the Bee Gees inventing the internet? – is a Chi-Lite-y six-minute-plus R&B ballad which is about twice as long as it needs to be, Barry emoting all over his shop to little effect; the song’s structure and sentiment would have required the Marvin Gaye of Here, My Dear to give it authority, though the anonymous tenor saxophonist does his best to liven proceedings up, and Dennis Bryon’s drumming is especially attentive (hear his “Enough!” snare hammer on the fadeout of “Love You Inside Out”).

“Living Together” might be a metaphor for the group, for all I know – the chorus goes “Why ain’t we livin’ together, livin’ together, instead of bein’ so far apart?” – and once the song gets past its elaborate trumpets and strings prelude, it’s nice to hear Robin finally getting a lead vocal (with Barry in his “normal” register answering him in the chorus) even if the super-falsetto effect falls just short of grotesque. Unfortunately, when the strings come in, I am reminded not of Chic but of ELO’s “Evil Woman.” “I’m Satisfied,” the only song on the record where Barry is actually with someone (there’s “Too Much Heaven” but that warns that love could just be “a dream to fade away”), simply tries to be too many things to too many people; Hall and Oates guitar strut, TK/“Rock Your Baby” organ and rhythms, Ethel Merman’s disco album levels of over-intensity, and the now irritating mass falsettos which sound like she-ee-ee-ee-eep.

And then, right at the end of an album which understandably disappointed many of the people who bought it, we get…Barry, and an electric piano (or possibly a synthesiser, IT DOESN’T MATTER)…and the sequel to “First Of May.” “You were a lovely child,” he starts, and the “oh dear” detector starts to rise, but no, it’s not about that; “I knew we were in love/We were alone to dream a dream.” Although the melody is broadly Stevie Wonder (“I Never Dreamed You’d Leave In Summer” would be a good comparison), Barry sings in his normal register, sounding remarkably like Bill Withers (with a touch of Aaron Neville vibrato). “We held our love and that held our hearts…” (a very Scott line there, don’t you think?)…and then there’s a pause. “Until…until…” Until what, Barry? There is no answer, except that his voice suddenly goes high and wordless; he is letting out the greatest of frustrated cries (Marvin, again, would have understood completely and immediately)…and the bird has flown.

Go back to the last voice you hear on Odessa, which is the same voice, after all the music has been systematically stripped from it:

“Don’t ask me why/But time has passed us by/Someone else moved in from far away…”

Because shit happened, because life changed, because “we” “grew up,” and sure we ain’t Chic or Funkadelic or even the Doobie Brothers – damn, that Michael McDonald, he can go up three registers in one breath of one syllable! – or for that matter Michael Jackson, but look, this is what we had to say, we were never gonna get shotgunned into doing it for the discos, and yes, the world turned against us again, and eventually will buy our songs as long as somebody else (from far away?) is singing them, but can’t you see this isn’t the indulgence of three rich men with nothing else to do? This is the album we would have made even if we had to support the Dooleys in Gateshead. Others do songs like “The Electrician” but we had our own ways. We - I - had no way of knowing…that eventually…

“I’m the only one left alive”

Saturday, 20 October 2012

BLONDIE: Parallel Lines

(#205: 17 February 1979, 4 weeks)

Track listing: Hanging On The Telephone/One Way Or Another/Picture This/Fade Away And Radiate/Pretty Baby/I Know But I Don’t Know/11:59/Will Anything Happen?/Sunday Girl/Heart Of Glass/I’m Gonna Love You Too/Just Go Away

If this were just any everyday music blog – for example, a blog about UK number one albums – you’d expect me to tell you that Parallel Lines was the second “punk” or should that be “New Wave” album to go to number one in Britain, at a time when it had really ceased to matter. Given that it entered our charts in late September 1978, and therefore took nearly five months to reach the top, it might be noted that the colossal success of “Heart Of Glass” as a single was the deciding factor in this happening. But that alone wouldn’t explain its omnipresence at birthday parties or on bedroom Dansettes, and nor do I think would it explain what a bi-focused album Parallel Lines is.

Then I remembered that on the inner sleeve of the original issue – not reproduced on the 2001 remastered CD edition – there were lyrics to a song called “Parallel Lines” which never seems to have had music written for it, let alone be recorded. And it spoke of “ships that pass in the night” and concluded that “it’s parallel lines that will never meet.” If, by “Evangeline’s stream – Evangeline’s dream” they meant the virgin Evangeline – the one about whom Nick Tosches imagines the dying Elvis to have nightmares in the opening section of Hellfire - then one of the album’s premises becomes clear. That cover, too; it might look impressively and implacably postmodern to unwary eyes but closer up it looks as though they are all in prison, or cut and paste together. Most of the group stand and grin like Beatles, but Chris Stein gives a rueful half-grin, and Debbie Harry stands afront, scowling. It is as though only these two know “the truth.”

Equally this is an album which starts with a desperate Debbie pleading “Hang up and run to me” and ends with a harried Harry snarling “Go away and stay away!” – and her roars and growls are such that one performance is not quite distinct from the other – and it becomes obvious that the parallel lines that will never meet here are the wanting of somebody, and the aftermath of somebody. On half the record Harry craves love like the rest of us would crave oxygen, while on the other half she reflects with some aggressive sadness on what a letdown it was. There is never any in-between. The song that encapsulates the two approaches best is “One Way Or Another” where both meet; in its first half, Debbie is ardent, artful, wanting to get her man (“I’ll meet ya!”), while, jump-cutting to the second half, she has him and now wants rid of him (“I’ll lose ya!.../Lead you to the supermarket, check out some specials and rat food”). In each half her fervency sounds identical. Nowhere on the album is she ever unambiguously with someone else, except unhappily.

In his sleevenote to the 2001 CD edition, producer Mike Chapman comments on how initially insular and withdrawn Harry and Stein seemed when he came to visit them with a view to doing Parallel Lines. Having heard the songs and deciding that they were great, Chapman then confesses to being something of a hard taskmaster in the studio, pushing the band to play these songs better than they had ever played them before. The approach works, however many band members were pissed off at the time (Clem Burke might have been the reincarnation of Keith Moon, but there are times when four to the floor will suffice), since even on its lesser tracks (“I Know But I Don’t Know,” “11:59”) the band play with a commitment that could only have come from being pushed very hard. Although Burke is the only individual player (other than Harry) whom the listener really notices – and he is rewarded by having the album’s last word with his drum commentary at the end of “Just Go Away” – the band work as a tightly integrated unit, and there is a fervid energy that pulsates through the record; on their super-speedy cover of “I’m Gonna Love You Too” they almost convince you that Buddy Holly invented punk rock, and the ensemble performance on “Just Go Away” in particular is a titanic swell of joint crescendo-led light (including the band’s yelled, English-accented “Go aw-AY!”s).

Jack Lee, once of The Nerves, wrote both “Hanging On The Telephone” and “Will Anything Happen?,” and both represent the kind of fusion of Count Five and the Shangri-La’s that you hoped might have come about with Blondie; the latter, in particular, is a sobering reflection on the former – hear the disappointed disquiet in Harry’s voice when it changes from hopeful to sober (“Will I see you again?/And if I do, will anything happen?”) which is worthy of that other professionally disappointed New Yorker Mary Weiss. “Sunday Girl” is the type of Blondie prototype pop that got adopted as a Commandment by the scores of predominantly Scottish (and mainly Glaswegian) indie groups which would appear from the mid-eighties onward – from the Shop Assistants to Camera Obscura – mainly because it is bright, peppy, mid-tempo and closer to girl groups than boy punk. But “Picture This” is not quite the glowing longing Harry’s performance might suggest; the chorus states semi-sardonically that “you’d be on the skids if it weren’t for your job at the garage” and the song concludes with a barked order: “Get a pocket computer/Try to do what ya used to do/Yeah.” In other words, the dream became an uncomfortable reality.

The album, like most albums, dips a little in the middle; Frank Infante’s “I Know But I Don’t Know” seems intent on being an Iggy Pop B-side (with very Pop-esque back-up vocals from Infante himself) while Jimmy Destri’s “11:59” is prototype apocalypse paranoia (“Today could be the end of me/It’s 11:59, and I want to stay alive”; Lena is right to comment that this is “a very Cold War album”). Neither is a great song but the band’s commitment and energy see them through relatively painlessly. “Pretty Baby,” written by Harry and Stein, raises the eyebrows with its references to a “petite ingénue” but the perspective here is more sorrowful than anything else; Harry, who lest we forget was thirty-three years old, with several lives behind her, when she made this record, seems to be reflecting on her own memories of the past, maybe thinking about the “teenage starlet” she herself could never be, with the song’s references to La Dolce Vita and “Incense And Peppermints” (the latter a US number one single when Harry was in the soft-rock psychedelic group Wind in the Willows). There is a moment where she sings “Ah, I, I should have known you’d look at me…and look away…oh” and the entire song pauses. That “oh” is one of the most touching things she’s ever done as a singer; behind it lie universes of premature disappointment.

That leaves, essentially, two songs, one of which was the group’s key to the kingdom; “Heart Of Glass,” that supreme marriage of drumkit muscle and Roland CR-78 mechanics (on the original 12”, though not here, Chapman finally allows Burke to cut loose at the end), of girl group past and peopleless future, their attempt to do a Moroder – a cover of “I Feel Love,” though never recorded, was a mainstay of Blondie’s stage act in 1978 – and a lament for the same misconception Freda Payne skirted around on “Band Of Gold” at the opposite end of the decade (“Soon turned out to be a pain in the ass”). If Harry sounds more detached than Payne ever did, it is detachment borne of painful experience (she makes the throwaway “Mucho mistrust” sound like Gray’s Elegy). And yet, as elsewhere on this Chapman-produced record, there are the elements of rinky-dink Farfisa organ and sporty wordless backing vocals (the one on “Heart Of Glass” reminds me of Green Gartside). You feel that underneath the pavement of electronic disco resides the sandy grins of Racey (although another Chapman-produced act, they were even more up for “it” than Debbie; singer/keyboardist Richard Gower’s performance on both record and video of “Lay Your Love On Me” drips with the gurning despair of somebody who is clearly dying for “it”; he can’t keep still for a second) but the airy airlessness of “Heart Of Glass” makes it a natural descendent of Bowie’s Low (but would Bowie have put such an emphasis on the word “amusing” as Harry does?) and, like much of this album, appears to sum up what was best about the seventies while also preparing to take all of it into the eighties (the instrumental break on “Picture This” anticipates R.E.M.).

Finally, though not the last track on the album, is its most disquieting track; “Fade Away And Radiate.” Even at a time when the word “radiate” had far more sinister connotations than it would now, this remains an exceptional and disturbing piece of work, and an unexpected blood-sister to Walker’s “The Electrician” and direct precedent to Harry’s own performance in Videodrome (as well as less obvious successors like Royksopp’s “The Girl And The Robot”); Burke’s drums sound like the loudest heartbeat ever recorded, while Debbie – there she is, watching her Other (but not “watching you shower” as she does for an hour on “Picture This”) sit there, mindlessly watching television, until eventually, like the girl in Bowie’s “TVC15,” he becomes the television (“Beams become my dream/My dream is on the screen” – and the film critic David Thomson has reminded us that the word “screen” can have two meanings; to show something to us, or to hide something from us). The music is slow, jittery and mournful (even the bizarre closing voyage into cod-reggae cannot dispel the uneasiness) and meanwhile Robert Fripp’s guitar is like the poltergeist on the other side of the screen, trying its best to come through, to be heard, to be noticed (this in turn ties the record in with things like Daryl Hall’s Sacred Songs and Fripp’s own Exposure - both 1979, neither a record you would want to listen to in a dark not of your own making). “Dusty frames that sill arrive/Die in 1955,” sings a numbed Harry – the year James Dean died, but also the year when television made it into the majority of homes, as though these filaments are still transmitting pictures, thoughts and people from the time Harry was ten into a 1979 “now.” The lines merge into closedown, the lights go out, and they tell us something we knew all along.

”Please don’t push me aside.”

Back then, we asked nicely.

Wednesday, 17 October 2012

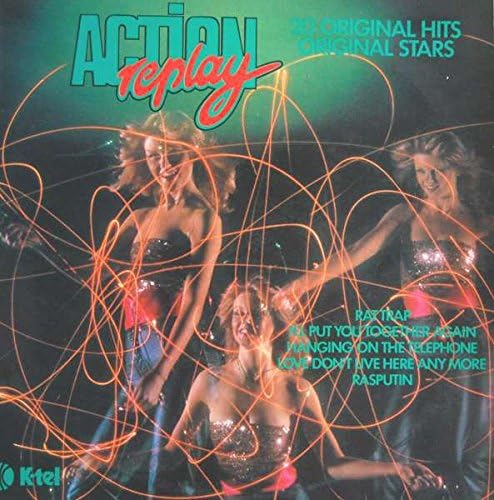

VARIOUS ARTISTS: Action Replay

(#204: 10 February 1979, 1 week)

Track listing: Rat Trap (Boomtown Rats)/Hanging On The Telephone (Blondie)/Giving Up, Giving In (Three Degrees)/I Love America (Patrick Juvet)/I Lost My Heart To A Starship Trooper (Hot Gossip)/Supernature (Cerrone)/Love Don’t Live Here Anymore (Rose Royce)/I’ll Put You Together Again (Hot Chocolate)/Anyway You Do It (Liquid Gold)/Y.M.C.A. (Village People)/Rasputin (Boney M)/Lay Your Love On Me (Racey)/Mexican Girl (Smokie)/Don’t Let It Fade Away (Darts)/Radio, Radio (Elvis Costello)/Drummer Man (Tonight)/Hot Child In The City (Nick Gilder)/Come Back Jonee (Devo)/Toast (Streetband)/Stumblin’ In (Suzi Quatro/Chris Norman)

It was nearing the end of the seventies, and K-Tel were determined to appear modern; hence the actually rather disturbing cover of their latest grab-bag of recent hits and near-hits concealing the same old proviso about track running times being altered, etc., which in practice means that “Love Don’t Live Here Anymore” and “Y.M.C.A.” are cruelly bisected while turgid dirges like “Rat Trap” and “I’ll Put You Together Again” groan on forever (the latter, though sung with evident heart by Errol Brown, is not so much a late seventies forerunner of "Everybody Hurts" but more the song from the musical that it actually was; Dear Anyone, about a magazine agony column; hence the rather clunky references to pens and writing in Don Black's lyric). That having been said, it is a better, more coherent album than Don’t Walk – Boogie, a lot surer about what it wants to be, with a much better hits-to-misses ratio (two number ones, and only one track here missed the UK Top 75). It’s also the first number one album I’ve come across in some time which advertises another record on its cover, namely New Dimensions by the Three Degrees, which is certainly more than worth getting but strange to find publicised here.

Analytically it can be broken down into the following components:

New Wave

The Boomtown Rats ended Disco Fever and begin this one; “Rat Trap” is documented as being the first “official” “New Wave” number one single, although its connections with any kind of wave, new or otherwise, are indistinct. Actually it starts out as a Thin Lizzy wannabe, with characteristically whispered/grumbled Lynott-esque vocals, before setting out to become a Barrytown version of Springsteen’s “Jungleland,” and plods on with lots of undirected anger. Yes, Billy and Judy, it’s a shithole and you’ve gotta get out of this place; now tell me something I didn’t already know.

“Hanging On The Telephone” does so much better, by setting its sights a lot lower; the music’s careful rush reveals that Blondie knew their Nuggets backwards and forwards, while Debbie Harry’s growls, purrs and cries of sexual frustration give a lot more punch to the song’s subject matter than some of the male contributors to this record. Supreme stuff, with a pointed and focused production by Mike Chapman, of whom more later.

Disco

The USA invented disco, but Europe picked up the ball and ran with it; the Three Degrees, needing a hit, hooked up with Giorgio Moroder and produced the brilliant “Giving Up, Giving In,” with its endless circulatory Roland patterns, aggrieved syndrum punches and a show-stoppingly angry lead vocal from Sheila Ferguson (“You can sweet talk to the wind”). Best heard in the context of the sequenced/segued first side of the aforementioned New Dimensions, but the song could have been written and produced this week and would have made a far better “comeback” single for Girls Aloud than the trying-far-too-hard “Something New.”

Europe kept hold of the ball; Jacques Morali was involved with both “I Love America” and “Y.M.C.A.” and both songs see America as a metaphor for the future; Patrick Juvet is Swiss and sings with a high-pitched but happy sense of bewilderment as though America will give him more than what he wants (though again readers are directed to the full fourteen-minute 12” with its multi-genre tributes). Village People lead singer and “Y.M.C.A.” co-writer Victor Willis always believed that the song was a signifier for the land of freedom, and in great part the song works so well because he sings it absolutely straight. He believes in what the song promises, and if there are any subtexts beyond that, it will be a surprise but also a bonus. “Ra-Ra-Rasputin” has already been dealt with, but Cerrone’s “Supernature” again demonstrates how Europe, and in particular Italy, were running back – a very 1968 lyric, this, about science and strange creatures, not to mention the central “Days Of Pearly Spencer” riff – to take a forward leap. Both Lena and I will have more to say about “Love Don’t Live Here Anymore” but for now it’s sufficient to think of the synth bass introduction as a midway bridge between “Ball Of Confusion” and “State Of Independence.”

UK Disco

Outside the developing realms of Britfunk, UK disco was lagging a little behind. “Anyway You Do It” was Liquid Gold’s first hit (and their last one until “Dance Yourself Dizzy” well over a year later); featuring singer Ellie Hope and co-written and produced by future Beach Boy Adrian Baker, it huffs and puffs where it should glide, and sounds like a Mad Lizzie exercise workout routine.

“Supernature” made our top ten mainly as a result of being used as the theme tune to The Kenny Everett Video Show, hence its placement here next to Hot Gossip, the dance troupe which allegedly went where Legs and Co. would not dare. If anything, both troupes now look strictly of their time and not remotely sexy (nor did either get me excited at the time), and “Starship Trooper,” famously featuring a young Sarah Brightman on lead vocal – you won’t recognise her by the time we get back to her – is really a very corny affair, with its single entendres, endless musical quotes, “Captain Strange”s and “droid”s; somewhat pallid when set next to “Stardance” or Dee D Jackson’s chillingly icy “Automatic Lover.”

Doo Wop Revivalism

“Don’t Let It Fade Away” was a slightly atypical record by Darts, the Showaddywaddy it was hip to like, but as would-be epic ballads go it’s not a bad effort, like a slightly less dramatic “Don’t Let The Sun Go Down On Me” crossed with a politer “Let It Be.”

Power Pop

Do you remember the very brief UK power pop revival in early 1978? Already people were looking for a way out of punk, and the prime movers here were a besuited group called The Pleasers, who received much music press coverage and expressed the wish that their debut single, a hopeful stab at the Who’s “The Kids Are Alright,” made #17 in the charts, since that was where “Love Me Do” had peaked. And you thought that record collection rock began in the nineties.

The Pleasers came to nothing, but Southend group Tonight sprung seemingly out of nowhere onto Top Of The Pops in early 1978 with the excitable and slightly overlong “Drummer Man” (Action Replay must be the only number one album to contain songs with words like “anaesthetise” and “majorette” in their lyrics) before, essentially, disappearing back into nowhere (one more minor hit single and an album that was recorded but I’m not sure was ever released). The Knack did this sort of thing so much better.

Post Modern

Akron’s Devo were heroes in my third year at school. I first heard the single version of “Jocko Homo” on, of all places, Alan Freeman’s Saturday Rock Show and was immediately hooked, buying both that and their follow-up cover of “Satisfaction.” “Come Back Jonee,” from their debut album, sees them moving steadily into a pop mainstream of sorts but still sounds bloody and admirably strange, like a Talking Heads cover of “Johnny B Goode” cut up and reassembled in not quite the same order. In the undergrowth, producer Brian Eno works patiently on his strategies for eighties pop.

On which subject, good morning to you, Paul Young, improvising (though there’s a composer credit) his way through some meditations on the nature and appeal of toast with a group which would shortly afterwards into the Q-Tips. With scraping knives, whistling kettles, off-handed scat singing and a lyric more disturbing than it might initially appear – is he really making toast at the age of three or four months? – it’s a wonder that this got anywhere near, let alone into, the Top 20; it is also, by some distance, the best thing Young ever did. But more of him anon.

Old Men, Get Out Of Those Young Girls’ Lives

Oh dear. The mirthlessly mirthful Racey, for those confused heads nostalgic for the days of Mud and the Rubettes, pounding their way through Z-grade Chinnichap (more Chinni than Chap, I’d say) bubblegum. “When I met you, you were seventeen/Not just another teenage queen.” It doesn’t say how old the singer is, and it is, like Racey and mainstream British seventies pop itself, rather creepy.

Everyone’s favourite post-punk pioneers Smokie roll up for a group composition “Mexican Girl” which is as good as you’d expect a Smokie group composition to be, i.e. lots of “sensitive” Spanish guitar and castanets (together with a throwaway “Then I Kissed Her” reference), a heart that’s “as big as a stone,” a singer who doesn’t know what “hasta la vista” means and another highly questionable lyric in general (“She looked so fine/Well, she was alright”). A shame, since Chris Norman does much better on the Suzi duet “Stumblin’ In,” mainly because Chinn and Chapman go for straight AoR and pretty much hit the target (it was a million-seller everywhere except in Britain).

Nick Gilder was born in London but raised in Vancouver; he was in the rock band Sweeney Todd with a very young Bryan Adams, and “Hot Child In The City,” despite doing nothing in Britain, was a US number one. Musically it does look forward to eighties Recklessness – it’s like a slowed-down Cars – but the subject matter of teenage child prostitution, where Gilder alternately addresses the object of his affections as “child,” “woman” and “child” before concluding “We’ll make love,” is not one you could get away with these days, and I don’t know that it should have been allowed to be gotten away with in those days. It leaves the same distaste in the listener’s mouth as things like “Young Girl” and one wonders where, if anywhere, it stops.

The Payoff

“Radio, Radio,” presented here in its full, unedited form, seems to be the point that this record might be trying to make. Costello had released one album full of slightly bitter love songs backed by musicians who would one day more or less back Huey Lewis, and then came the Attractions and Nick Lowe and a second album of friable anger that spoke directly to every decent, resentful geek ignored in the classroom or passed over at work. “Radio, Radio” emerged as a stand-alone single in late 1978 and was quickly adopted by radio stations blindly assuming that any song with the word “radio” in its title was worth playing to infinity.

An extremely blind assumption here, since Costello is attacking the very nature of British radio; the Attractions have rarely sounded more febrile, while the singer barks about a broken old radio switch and having to sit through late night ‘phone-ins and Top 40 carousels which present a nightmare inverse vision of the Britain he thinks he knows and which, he also thinks, may be slowly summoning up its rearguard forces to obliterate him. The closing citation of Richman’s “Roadrunner” is lethally ironic, and the suggestion is that not just that British radio, but the whole of British culture and society, has been built on a false and crooked premise. It is frightening and compelling, and helps lead us further into a year where society is not going to be quite as docile or acquiescent as one might think – although many of the upcoming number ones appear to suggest that a silent majority liked oppression and an early bed more than they might pretend to express.

Monday, 15 October 2012

VARIOUS ARTISTS: Don't Walk - Boogie

(#203: 20 January 1979, 3 weeks)

Track listing: Boogie Oogie Oogie (Taste Of Honey)/More Than A Woman (Tavares)/Singin’ In The Rain (Sheila B Devotion)/I’m A Man (Macho)/Summer In The City (Evolution)/From New York To L.A. (Patsy Gallant)/Just Let It Lay (Gonzalez)/Whodunit (Tavares)/Bring On The Love (Why Can’t We Be Friends Again) (Gloria Jones)/Substitute (Clout)/Black Is Black (La Belle Epoque)/Dancing In The City (Marshall Hain)/You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real) (Sylvester)/Heaven Must Be Missing An Angel (Tavares)/Empire Road (Matumbi)/Nice And Slow (Jesse Green)/Sun Is Here (Sun)/I Love To Boogie (T-Rex)/Stardance (John Forde)/2-4-6-8 Motorway (Tom Robinson Band)

The catalogue number for this album was EMTV 13, meaning that EMI had temporarily put the 20 Golden Greats franchise on the backburner in an attempt to broaden out its TV advertising reach. EMTV 12 had been the series’ first Various Artists compilation, The Big Wheels Of Motown, which made #2 in October 1978, and this probably felt like a very decent idea for a follow-up money spinner at the time.

Given that this album goes out of its way to try to convince us that it is not Disco Fever, however, it ends up as a rather unfocused, discontinuous and slightly desperate mix of overly disparate types of music, unsure whether it wants to be a genuine dance music compilation, or a connoisseur’s choice of non-obvious non-hits (seven of the twenty tracks made no impression on the UK singles chart at all), or a straightforward pop hits album. Evidently EMI, having to choose all the tracks from their own catalogue (and Motown being ruled out for obvious reasons), had only a limited amount of music to play with and repackage, but apart from the slightly morbid fascination involved in having Gloria Jones and Marc Bolan on the same record, I am unclear from this evidence what, if any, aesthetic links there are between A Taste Of Honey and the Tom Robinson Band. Best, perhaps, to think of it as a sort of “Bedsit Disco” mixtape, the sort of thing someone who didn’t necessarily know about dance music – a student, for instance – would buy and play in the assurance that owning it and listening to it would make them cooler, more up-to-date, and therefore to go through it artist by artist (N.B.: there are too many examples to credit individually, but the majority of insights which follow were suggested by Lena).

A Taste Of Honey

Their one moment of glory, and a very welcome start to the proceedings; a genuine disco group from Los Angeles whose singers played guitar and bass as well as sang. I think it’s Janice-Marie Johnson on lead vocals (and bass) and it’s a remarkably sophisticated dance records with its suspended Heatwave harmonies, rock guitar fills (from co-singer Hazel Payne) and an admirably pining-alternating-with-sardonic lead vocal by Johnson (“Listen to my bass-IST!”). Drummer Donald Ray Johnson is most definitely not the same Donald Johnson who drummed for A Certain Ratio.

Tavares

Almost straightaway we come to one of this record’s central problems; the relative paucity of material available can be the only explanation for there being no less than three Tavares tracks, including one aimed at the three Shetland crofters who hadn’t yet bought Saturday Night Fever (although on this listen to “More Than A Woman” it is interesting to note how its flute flutters descend from the Main Ingredient’s 1972 hit “Everybody Plays The Fool”). Shorn of its disco beat, “Heaven Must Be Missing An Angel” could be the Ink Spots. “Whodunit,” meanwhile, is late seventies soul paranoia in extremis; lead singer Chubby Tavares steadily becomes more and more panicky, finally ordering everybody up against the wall, summoning up Baretta and Dirty Harry, and howling “We were gonna get MARRIED!” at fadeout. In which case, Chubby, what the hell did you think you were doing letting her go out dancing by herself?

Sheila B Devotion

Long-standing French pop star Sheila, perhaps best known there for her 1964 French reading of “Doo Wah Diddy Diddy,” went disco, and it’s a mark of how disco rapidly took over the world that all sorts of seemingly incompatible songs were given the disco treatment. Actually her heavily accented “Singin’ In The Rain” is bright and lovable, and in Britain at any rate did better in the charts than “Spacer.”

Macho

A real find, this one; an Italian studio project set up by the late Jacques Fred Petrus, who would later co-found Change, going all out on a bombastic Hi-NRG reading of Steve Winwood’s “Comin’ Home Baby” Mod rewrite. Singer Marzio Vincenti busts several guts, and several more dictionaries, to boom the song out in wonderful cod-English while the beats are depth charge heavy, the bass slapping away like an English public school prefect, and the song’s central riff resonating from a sinister, Gothic organ. For the whole experience, though, you need the full-length 17:37 album/12” version, which happily recently resurfaced on a Disco Discharge album.

Evolution

I could find out nothing about this lot, and this cheesy Lovin’ Spoonful reworking seems to be the only thing they ever did. Note the curiously cheerful vocal, given the song’s subject matter; the overall impression is one of Vince Hill going to the disco (that triple “Hot town!” bark!).

Patsy Gallant

A highly controversial hit record at the time; Canadian actress and singer Gallant discofying a nearly sacred Quebecois anthem, “Mon Pays C’est L’Hiver” to excellent effect with a very typical Canadian ambiguity towards fortune and fame; she keeps us guessing whether she’s lamenting being famous or alone, or enjoying it (the sly “but was it/were you really meant for me?”s), but she sounds absolutely exultant and liberated. “To sing and be free”; really, that is all that many people desire.

Gonzalez

Co-produced by Gloria Jones, but even she can’t save this from being a rather limp Brit appropriation of Parliament, Ohio Players and Rose Royce. They try their best (“Black is white and white is black,” “Blow your mind in short time”) but it’s rather like hearing Showaddywaddy trying to be funky.

Gloria Jones

And here’s the lady herself, with a record cut in L.A. with top drawer musicians, Ray Parker Jr, Joe Sample and Wah-Wah Watson amongst them, which was intended to come out on Motown but for whatever reason never did. Its full-length (7:02) version has also recently had the Disco Discharge reissue treatment, and it’s a very touching mid-tempo ballad with skittering lead guitar and heartfelt vocals (Bolan heard it just before he died and insisted that it be a single, and the personal effect on Jones’ performance cannot be un-felt) though its balance of the optimistic (summery flutes) and cautiously pessimistic (“Bring on the winter”) suggest that Saint Etienne might do a good cover of this.

Clout

No, I don’t know what this ode to being a human doormat is doing on a dance album either (though maybe French Carrere insisted that EMI take this along with Sheila B Devotion). An all-girl rock group from South Africa with an old Righteous Brothers song; as it made #2 in Britain as a single, wait until Lena gets to it for further comment.

La Belle Epoque

This also made #2 in the UK, and once you get past “VE LIKE ZE MOO-ZEEK! VE LIKE ZE DISCO SOUND!” intro it is a rather flimsy cover version, again sung with baffling cheerfulness (“Whoo!” the girls exclaim at regular intervals). “Yes,” drawls lead singer Evelyne Lenton, “it’s about time we all go back to Black Is Black. C’MON!” Back to the sixties, or back to misery?

Marshall Hain

Top three in 1978, and clearly a harbinger for the aspirational “pop” of that anagrammatic year 1987, they were a duo of keyboardist Julian Marshall and singer/bassist Kit Hain. Too slow for any disco, the “dancing” here can only be viewed as a metaphor, and Hain’s vocal seems determined to be Christine McVie. Marshall became a Flying Lizard only a few months later, while Hain concentrated on being an extremely successful international songwriter. But I don’t know what this is doing here either; I think it would quite like to be George McCrae, but lacks the necessary polyrhythmics.

Sylvester

LIBERATION! Straight out of L.A., the late, lamented Sylvester James, along with Patrick Cowley, made one of the greatest of all singles. How glorious it still sounds, even in this edited-down form, with its petrol station string synthesisers, its ecstatically androgynous vocal, its fearless sequencing, its deadpan piano, its expression of boundless joy at finally breaking down all closing doors. Here it’s like somebody has suddenly thrown open a window to welcome life and hope. Pop music sung and played like it SHHHHHHOOOOOOUUUUULLLLDDDDD!!!!

And, of course, like “Heaven Must Be Missing An Angel,” it is virtually a gospel song, a hymn.

Matumbi