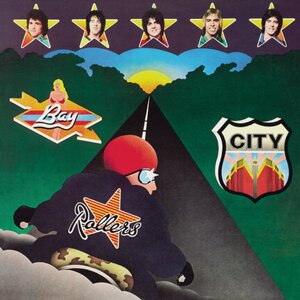

(#155: 3 May 1975, 3 weeks)

Track listing: Bye Bye Baby/The Disco Kid/La Belle Jeane/When Will You Be Mine?/Angel Baby/Keep On Dancing/Once Upon A Star/Let’s Go/Marlina/My Teenage Heart/Rock And Roll Honeymoon/Hey! Beautiful Dreamer

Back so soon, boys? Actually I do derive more than a shred of comfort from the fact that, had Twitter been going in 1975, it would have been overrun, not by Beliebers, but by their spiritual ancestors, the Rollermaniacs; and, like Our Justin, the appeal of the Rollers at their peak was practically sexless, or ignorant/blissfully unaware of sex – their blanket was one of comfort and security, and we shouldn’t forget that their second number one album, much like their first, is aimed at twelve-year-old girls rather than Steely Dan fans.

Whether the Rollers listened to Pretzel Logic in their own time and agonised is another question, but what is clear from Once Upon A Star is that they had been riled, badly, by the print about session musicians on their hits, about being Martin and Coulter’s puppets, and were determined to prove that they themselves were the attraction. Thus Martin and Coulter were shown the door (whereupon they immediately turned their attention to, amongst others, a promising Glasgow band called Slik) and replaced by former Sweet and Alex Harvey producer Phil Wainman, who, with Johnny Goodison, came up with three of the album’s dozen tracks. Two others were covers, leaving seven tracks written by Eric Faulkner and Woody Wood (with Les McKeown helping out on two of these).

The results are inevitably mixed and present a picture of a band in a tug of war with itself. Of the Wainman/Goodison songs, “When Will You Be Mine?” is a lame rewrite of “When Will I Be Loved?” clumsily superimposed on the standard rolling piano Rollers template, “Let’s Go” is the Archies doing the Glitter Band, strangely bloodless, even with its “Saturday Night’s Alright For Fighting” guitar line and key change (though, as Lena pointed out, speed the song up a bit and make it more antisocial, and you have the Ramones), and “Rock And Roll Honeymoon,” belted out by an enthusiastic Alan Longmuir, is perfectly serviceable power pop, complete with “Here Comes The Bride” Roy Wood-ish sax interlude, which would be venerated had it been Eric Carmen and the Raspberries.

Of the two covers, “Bye Bye Baby” was the biggest hit they ever had, McKeown sounding strangely elated about being torn between two lovers while the Roller formula met its apogee (one has only to listen to the flaccid “My Teenage Heart” to appreciate how difficult this formula was to reproduce), while “Keep On Dancing” was a mechanical retread of the 1971 original, deprived of Jonathan King’s production tricks and Johnny Arthey’s arrangemental genius – wah-wah guitar replaces organ and the false ending is substituted by McKeown bellowing over the least convincing crowd noises I have ever heard on any record; is that a baby squealing towards the end?

Left to Faulkner and Wood’s devices, one can sense how brave the struggle was for the group to assert themselves; the question being whether they had enough resources as a group to carry out their ambitions. On this listen my answer must be no, although it’s hardly for want of trying; if nothing else you are witnessing the sound of a band trying their damnedest. One’s heart does not warm up with expectation, for instance, at the prospect of a song entitled “The Disco Kid,” which if you were a Roller is about the last title, or idea for a song, you’d use. And McKeown’s introductory grunts of “Check it out!” and “UUHHH!!” do not exactly raise hopes. That being said, it’s a fair attempt, the wah-wah and clavinet work turning it into a sort of Junior Showtime “Trampled Under Foot,” with an interesting use of echo (“He’ll shake you DOWN!”), if an ultimately unconvincing one (“They call him Disco Kid!” announces McKeown at one point; presumably he doesn’t mean the guitarist who three years later appeared on Sun Ra’s Lanquidity). Similarly, “Angel Baby” isn’t much more than an attempt not to be “Be My Baby,” but I can’t think of any twelve-year-old 1975 girl who wouldn’t have melted at McKeown’s Morningside talkover.

It’s when they stretch their limbs in other directions that the Rollers really begin to engage my interest. “La Belle Jeane” thinks it’s The Band’s “When I Paint My Masterpiece,” with its ample mandolin and accordion deposits and tricky Franglais, but it’s not a bad thing to think, and the track gets truly interesting when the band try to cut the dummy loose, with Derek Longmuir’s minimalist drumming and its sections of dissolute harmonies, the chord structure at times reminiscent of Roy Harper’s “When An Old Cricketer Leaves The Crease.” The closing “Hey! Beautiful Dreamer” is a Beatles pastiche – Harrison guitar, verse and chorus, Lennon piano and middle eight (“How can you feel nothing is real?”) – which nearly pulls it off, its disjointed ethereal harmonies resolving in an angelic harmonic ascent towards fade, as though the band are fading from our grasp forever.

But the Faulkner/Wood Rollers work best, unsurprisingly, when dealing with the subject of fame and stardom (yes, this is classic, slightly self-conscious second album syndrome). The title track has ambitions beyond its grasp, looking for harmonic adventure and arrangemental imagination (well, there are a couple of clarinets) although stylistically it rather resembles Carl Wayne’s New Faces theme “You’re A Star” with perhaps a dash of CSN’s “Our House.” Still, it’s a sad but generous reflection on the transience of fame, etc. (“Your friends all drinking champagne from your hands”). And “Marlina,” one of the two tracks co-written with McKeown, cuts the deepest (although the sleeve is at pains to point out that the names “Marlina” and “Jeane” are “purely fictitious”); about a young girl seeking fame (and escaping from her “silver stallion” fantasies, although the song already knows that she won’t), Faulkner goes for the full Rod Stewart violin/mandolin deal, but the song is sung a lot more generously; McKeown’s voice is at times not a million miles from that of Roddy Frame, and overall the song structure, with only slight alterations, is that of Teenage Fanclub’s “What You Do To Me.” Here, though, is the impression that the group actually cares about what they’re saying.

Indeed three of the last four tracks on Once Upon A Star would not have been out of place on, say, Grand Prix or Songs From Northern Britain; and perhaps it’s a truism that the Rollers’ real legacy lies in their intended, and unintended, subsequent influence on pop. It’s also probably true that the average 1975 Rollermaniac wasn’t too bothered about self-authorship and just wanted to luxuriate in the sound and spectacle of the Rollers being themselves. But, at least here, the Rollers don’t get another chance; Wouldn’t You Like It?, which followed just a few months later, is overall a stronger album but only peaked at #3, and 1976’s Dedication was a dignified swansong (not that it was intended as such) but by its time sorely out of place. By that time the fleeting Stateside success had already fizzled out, and the real story of a decent but trapped group – nervous breakdowns, attempted overdoses, personnel changes, internecine band fights, court battles over unpaid royalties, not to mention the extremely thorny question of Tam Paton, the Walton Hop, and all that – had begun to leak out. For now, however, here stand the Rollers, a group who probably would have had a much better chance on Creation Records in 1995, if not an equivalent Twitter overload.