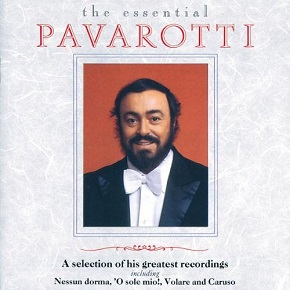

(#409: 23 June 1990, 1 week; 7 July 1990, 3 weeks)

Track listing: Rigoletto, Act 3 - "La donna è

mobile"/La Bohème, Act 1 -

"Che gelida manina"/Tosca, Act

3 - "E lucevan le stelle"/Turandot,

Act 3 - Nessun dorma!/L'elisir d'amore,

Act 2 - "Una furtiva lagrima"/Martha,

Act 3 "M'appari"/Carmen, Act

2 - "La fleur que tu m'avais jetée"/Pagliacci, Act 1 - "Vesti la giubba"/Il Trovatore, Act 3 - "Di quella pira"/Caruso/Mattinata/Aprile/Core

'ngrato/Soirées musicales - La Danza/Volare/Funiculì,

funiculà/Torna a Surriento/'O sole mio

Was Hillsborough the excuse

needed – that is, needed by vested interests - for excluding ordinary people

from the game of football? I could go on at some length about this but would

instead refer you to Adrian Tempany’s remarkable, poignant and deadly damning

book And The Sun Shines Now. Tempany

writes about that Sunday afternoon and its long and agonising ramifications in

immense and frequently painful detail. He speaks with the unquestionable authority

of someone who was actually present at Hillsborough and who indeed almost died

in the crush, and his account of the subsequent years of action – or, in some

vested interests, determined inaction – reads like a never-to-be-written David

Peace novel (and Peace himself has said that this is the one topic about which

he can never write; to get a hint of what he might have said, read the account

of the 1971 New Year’s Ibrox disaster in Red

Or Dead – and even then you wouldn’t get half of what the impact of

Hillsborough was.

After Hillsborough, however,

football was “legitimised”; Dr Karl Miller in the London Review of Books wrote of Paul Gascoigne as “strange-eyed,

pink-faced, fairhaired, tense and upright, a priapic monolith in the

Mediterranean sun – a marvellous equivocal sight.” Terraces became all-seaters.

Ticket prices shot up to meet the need to attract international playing stars

and maintain satellite TV coverage deals. The Premier League – essentially four

or five “big” teams and fifteen or sixteen patsies – was established as a

monolith in its own priapic right. In that same year – 1992 – Fever Pitch: A Fan’s Life, written by

Nick Hornby, an English graduate of Jesus

College, Cambridge, was published and some voices

whispered about the game now being “acceptable” (certainly Fever Pitch is very well-written and does considerably more to

convert unbelievers than the same author’s subsequent writing, both factual and

fictitious, about music).

But finance, international

finance, became the prime concern. Never mind the games, even, let’s get those

Manchester United T-shirts worn in Vladivostok.

Teams became uprooted from their origins – in some cases (Wimbledon FC)

literally – and degenerated into brands. The game suffered, too, with too many

needless fixtures added in for the convenience of television viewers,

especially the floating voters of TV who didn’t fundamentally like football but

would tune in every now and then. As the art of defending turned into a science,

something that could be taught and studied, defenders became stronger and goals

became fewer; hence the endless, listless 0-0 draws which constitute most of a

Premier League season, or the cynical 0-0 draws, the only purpose of which was

to maintain a result, a profile, rather than entertain the people who had paid

good money to come and watch it.

No child grows up dreaming of

being involved in a solid 0-0 draw. They want goals, and lots of them; they

want drama, excitement, and not the stapled-on kind of “drama” which

constitutes penalty shootouts and which does not constitute football as any

sane person would recognise it. Hence it is almost irrelevant that Leicester City is owned by a Thai billionaire with

plenty of resources to pump into the club; this past season they were the

underdogs, the one to act as a team rather than an assemblage of sullen,

entitled individuals, the one to play together while the other teams, by and

large, primped and posed.

One may look at the current

events in Marseille and find varying reasons – the Russian hardcore put them up

to it, the French “ultras” were having a go at the supporters, the security and

facilities in the city were laughably non-existent – for them, and perhaps

wonder why the forced gentrification of football needed to happen in England –

the other three constituents of the United Kingdom tell a different story, or

stories - if this was the result.

But yes, it is now all about

international stars and their heroic tales, their defiance in the face of

impossible odds, their lives and doings off the pitch. And it is not quite what

was there before. Most people who in the old days would have paid next to

nothing to go to a home game, even by a comparatively major team, now stay in

and watch the games on Sky Sports or online (or on their smartphone), or listen

to them on the radio. The notion of community – that this is a rite of maturity

to which parents take children to learn how a team of players can work together

for a greater good – has vanished.

At the 1989-90 bend in the river,

one of the major turning points could be ascribed to whoever in the sports

department of BBC Television had the idea to use “Nessun Dorma!” as the theme

to their 1990 World Cup coverage.

* * * *

In the second half of 1990, plans

were also being drawn up for a commercial radio station devoted to classical

music. Although, test broadcasts of birdsong notwithstanding, Classic FM did

not come fully on air until September 1992, important moves were being made,

mergers agreed, backers sought. The subtext was clear: this would essentially

be Radio 3 without all the difficult bits, including any obligation to provide

a public service, to make things happen rather than reflecting the shinier

parts of them.

It has always been the easy route

to fame and fortune – it is certainly not confined to the last half-decade or

so – to let people off the hook and tell them not to bother with that difficult

and troublesome “new” music that they find so problematic, or, in Classic FM’s

case, skip the best part of a century between Debussy and Arvo Part and forget

all that awkward German and Austrian stuff that happened in between. This

benign philistinism worked in parallel with Hornby’s attitude to pop music; a

catastrophic misreading of the common good as all people should like this music, that work of art, and that if they exhibit the slightest hint of

independence of thought they are to be excommunicated, damned, considered “weird”

or worse; in terms of which the old Soviet Union would have been proud, it was

a case of art for the people and anything different was imperialism’s most

stalwart servant.

That belief has subsequently

ossified into gospel. Radio must only play one of two hundred or so “proscribed”

records for fear that the casual listener might immediately switch to another

station at the faintest scent of anything unfamiliar or different. One cannot

move for newspapers and magazines weekly offering canons, lists, minimal rejigging

of the same basic feeding matter. Anybody wanting anything more than crazy golf

and Muzak is automatically Unmutual.

It is true that such things as

Gorecki’s 3rd and Bryars’ Jesus’

Blood (the remake featuring Tom Waits, alas, rather than the immeasurably

superior 1975 original) would not have found such great commercial success

without Classic FM’s patronage. But the station seeks to follow rather than

lead, to echo rather than to initiate, and its millions of listeners, wanting

something quiet and undemanding to listen to in the car or office or kitchen,

are happy to abide by that. Is pointing this out “spoiling things,” and, if so,

whose spoils are they?

* * * *

The Godfather, Part III opened in cinemas just before Christmas 1990. Coppola was not keen on a third instalment of a story which he thought had been adequately told in the first two films, but he needed the money to stave off bankruptcy. When I first saw it, in a nearly empty cinema in the West End on the first weekend of its release, I thought it was terrible. Pacino had made Michael Corleone look aged, bored, listless, distracted. Sofia Coppola, as an actress, had not yet perfected the blank space that she would subsequently put to great use as a film director. As Robert Duvall had declined repeating the part, primarily for financial reasons, George Hamilton, of all blank spaces, was suddenly, and (in)effectively, Tom Hagen.

The Godfather, Part III opened in cinemas just before Christmas 1990. Coppola was not keen on a third instalment of a story which he thought had been adequately told in the first two films, but he needed the money to stave off bankruptcy. When I first saw it, in a nearly empty cinema in the West End on the first weekend of its release, I thought it was terrible. Pacino had made Michael Corleone look aged, bored, listless, distracted. Sofia Coppola, as an actress, had not yet perfected the blank space that she would subsequently put to great use as a film director. As Robert Duvall had declined repeating the part, primarily for financial reasons, George Hamilton, of all blank spaces, was suddenly, and (in)effectively, Tom Hagen.

I thought that the central plot,

involving laundered Vatican money, was

ludicrous and flimsy. The villains were largely cartoon cut-outs and so the

ritual mass assassinations at the end rang hollow. Only Andy Garcia, as

Vincent, demonstrated any vitality or energy, as if to remind Michael how a

living Sonny might have run things.

There is some improvement if you

watch it as part of the DVD Godfather

Saga trilogy; Walter Murch’s editing had been curtailed in a rush to meet

Christmas opening times at cinemas, and on the DVD much interesting additional

material is restored, giving us a better picture of Michael in his autumnal

musings (since it is still, ultimately, Michael’s story).

Watching it now, however, in

tandem with its two predecessors, one wonders at the brutal efficiency with

which an organisation will endeavour to protect itself, as well as wondering

what it is protecting, apart from a dull obeisance, a ritual, a closing of

doors to the outside world, including other, parallel organisations. Indeed,

parallels with the current state of the United States of America may not be

far-fetched. One notices how anybody who demonstrates the slightest

independence of thought is efficiently removed from life’s equation. Not that

Barzini, Moe Greene, Hyman Roth or Fredo were by and large good people. But one

does get the sense of possible futures being blocked off.

The real problem for me now in

the third Godfather movie is Joey

Zasa. We know – though are never shown proof – that he is a rather nasty piece

of work, peddling drugs to the blacks and Hispanics, turning Little Italy into

a slum, and that something has to be done about him. We also know, given their

long-term mutual hatred, that Vincent will be the one to do what has to be

done.

The trouble, however, is that Joe

Mantegna’s Joey is too good. He

saunters into and steals every scene he’s in, even his own death in the

procession. He is hip, cool, smart and arrogantly funny, and next to him the

ageing Michael appears as though a dinosaur. We want more of him, maybe a

lifetime of him. If Coppola had wanted to make a good sequel, he could have cut

out all the killings and big setpieces altogether and made Godfather II a buddy-enemy comedy where Joey and Vincent loathe

each other but are forced to work together for the greater good.

But there is that weakness –

imposed or instinctive – for the calamitous, operatic finale, played out

against a production of Cavalleria

Rusticana, that earlier bloody tale about betrayal set in Sicily, an early

move towards the verismo trend which

overtook Italian opera in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries – a

move away from romps about kings, queens and gods and towards the tragedies of

ordinary people. The question is: would a Michael Corleone ever have settled for

being ordinary? That he did not explains his ultimate, lonely tragedy.

* * * *

All this, perhaps unfairly,

converges on the 1990 phenomenon of Luciano Pavarotti, on the grounds of a

compilation album which spans his work from 1971-89. After all, the younger

Pavarotti had fondly nurtured dreams of being a goalkeeper before being

reluctantly persuaded to take up music as a career option instead.

The compilation was advertised on

television, and I note that my copy still bears a football-shaped sticker

advertising both “Nessun Dorma!” and its use in Grandstand. The notion may have been to attract people who would

not ordinarily be attracted to opera or classical music in general. It was the

first classical number one album, certainly the first number one album by an

Italian act, and the first number one album to be sung entirely in other

languages (Italian and French).

Before we go any further, I

should just like to point out that, as albums go, The Essential Pavarotti is a tremendous record, one of the best you’re

likely to encounter in this whole run, and I would recommend visiting your

local charity or thrift shop immediately to rescue a copy. You can see from the

above track listing that it has every obvious song and aria you could imagine

in this context; and yet this album contains some of the deepest and most

highly realised music that has ever been composed or performed.

The album divides evenly between

operatic arias and popular songs, in no particular chronological performance

order. One can view how the slightly reedy voice of seventies Pavarotti evolved

into the confident tenor of the eighties; the album’s first half cleverly

begins and ends with recitatives from Verdi and one can witness how the rather

stiff, haughty tenor of “La donna è mobile” evolves into the imperious,

percussive and absolutely commanding voice of “Di quella pira.” Overall,

however, the impression, as Lena remarked to

me, is one of a soul singer, a genuine artist. Not the Glenn Gould thing with

the Artist being their own Artwork, but someone who turns up on time to the

studio or the opera house, has rehearsed their lines well – for opera demands

that great singers should also be great actors – knows their art inside out and

is technically and emotionally capable of giving the song as good a performance

as possible. A soul singer because the only point of comparison that we could

find with Pavarotti was Levi Stubbs; someone who gives a definitive delivery of

every song they sing and who more importantly make you believe everything they are singing, even if you don’t know the

language in which they are singing or know enough about opera to realise that

they are singing something completely ludicrous. Pavarotti’s performance on “Che

gelida manina” brought, of all singers, Matt Bellamy of Muse to our minds, not

so much because of any vocal resemblance, but because there is a similar

commitment to the epic, the definitive and grand statement – even when, as in La Bohème, intimacy is largely required

from the lead performers.

As I say, no obvious song is

missed out, and perhaps no opera plot (prior to the twentieth century) was too

obvious. Even when they are not comic operas – and it is quite startling to

realise that even Carmen was

considered one in its day – their plots, even when dealing with everyday

cuckolded clowns, were elaborate, fantastical myths, all kings, queens and

dukes, or the sudden giving and equally sudden withdrawal of love, with much

blood and gore mixed in, not to mention demonstrably artificial plot or

character twists. This was no different from Shakespeare in his Globe Theatre

days, or for that matter from the ancient worlds of Plautus or Aristophanes; as

Game Of Thrones has demonstrated,

humans still need fantastical stories, legends, myths – something which is

bigger than them but makes them feel yet bigger, since every hero and heroine

has a fatal flaw. Stories are what keep us going, nourish and sustain us.

As fine as the showpieces from Tosca and Pagliacci are in Pavarotti’s hands, he is even more impressive when

he turns the volume down. In this collection you will find no sign of his

interpretations of Gluck or Haydn, or for that matter Schoenberg, but the comic

opera performances are quite touching. Of these, Donizetti’s “Una furtiva lagrima”

is the more outstanding in that Pavarotti does not go for the big finish but

keeps the tone medium, meditative – his character is wondering whether the

solitary tear he saw her cry means something, represents love. Even in his

closing accapella feature he exhibits

great technical and emotional control.

It is impossible for me to

dismiss or belittle this music as it is in my DNA; this is music with which I

grew up, some of which I experienced first-hand (for many of these songs are

derived from Neapolitan music, some sung in Neapolitan slang). That also goes

for the album’s popular/populist second half. His “Core ‘ngrato” is a tremendously

touching and fulfilling performance. Only his 1984 “Volare” seems a slight

miscue. Performing under Henry Mancini’s direction, the song starts (and indeed

ends) like an outtake from Scott 4

with echoing chants and free-floating strings. It gradually assumes some form

of recognisable order as it proceeds, but the impression here is one of a

polite battle; Pavarotti clearly wants to sing the song his way, but Mancini is

equally determined to do as he does. It doesn’t quite finish in a draw.

Nevertheless, I note that the closing two songs, both performed brilliantly,

were the foundations of consecutive number ones by Elvis Presley – like

Pavarotti, born in 1935 – and given how both these young men idolised Mario

Lanza, the penny drops; this is the record Elvis would have made if rock ‘n’

roll had never happened and he had been given the opportunity to take better

care of himself.

But the song at which we must

pause, and in many ways the most remarkable song on the record, is the one

which sounds utterly of its time. “Caruso” was written and originally recorded

in 1986 by the Italian singer-songwriter Lucio Dalla. It was inspired by

thoughts of the last days of the great tenor, as he looks in the eyes of his

beloved (by now, in Caruso’s case, it was one Dorothy Park Benjamin) fully

aware that he is about to die. Several songs on this collection find Pavarotti staring

in the face of imminent death – even Turandot

is about the need to know the answer to three riddles, on joy of royal marriage

or pain of death (you see what I mean about intrinsically silly plots – Pavarotti

transcends the silliness and turns “Nessun dorma!” into a defiant cry of a

challenge to the whole world; “I WILL WIN [with or without your help]!”) – but only

“Caruso” finds its protagonist actually approaching the end of his life.

“Poi all'improvviso uscì una

lacrima (furtiva?) e lui credette di affogare,” he sings, which means: “But

then, a tear fell, and he believed he was drowning.” The song’s second half is

an adaptation of a Neapolitan love ballad from 1930 entitled "Dicitencello

vuje" and, in an affecting echo of the other end of the second half of

this record – the compilation is even structured like a football match – the word

“Surriento” is heard. The chorus is a

cry of love, noting that “It is a chain by now that heats the blood inside of

our veins.”

Pavarotti recorded his version in

1988, accompanied by not much more than a Fairlight by the sound of it, and it

is breathtaking; his yearning sounds deeper and higher than anywhere else on

the record, and we could not help but think, yet again, of Billy Mackenzie. The

free kick somehow lands in the middle of the New Pop square, the singer’s

performance is as great as any of the truly great performances to be

encountered in this tale. The nearly sixty-eight minutes of this record go by

as a whisker, and you forget that this is supposed to be 1990, the year in

which so much of our present-day pain was allowed to be legitimised, but are

never allowed to forget, in this week of decision, what European music and

European musicians have done to enliven and indeed enable the art of this land.