(#396: 30 September

1989, 1 week)

Track listing: Steamy

Windows/The Best/You Know Who (Is Doing You Know What)/Undercover Agent For The

Blues/Look Me In The Heart/Be Tender With Me Baby/You Can’t Stop Me Loving

You/Ask Me How I Feel/Falling Like Rain/I Don’t Wanna Lose You/Not Enough

Romance/Foreign Affair

In the last week of September 1989, two albums by leading

black female artists were released. I don’t really know whether it is possible

to find any meaningful link between the two but some may yawn that, yet again,

the lesser of the two was the one to make it to the top. Not that anyone should

yawn at Tina Turner, somebody who has lived through things so horrible that

even Annie Lennox could never imagine them; I can’t think of anybody else who

better deserves to be an international pop star, or brand, whose name they know

how to spell in Vladivostok.

She sprang back into life five years before with Private Dancer and then, like Presley in

Vegas, settled down for maximal tourist/hotel lobby appeal. Indeed the

snapshots on the cover of Foreign Affair

suggest a jetsetter who can go anywhere and do anything. Sashay up the Eiffel Tower?

No problem! Look at the Herb Ritts centrespread and you might wonder how much

of this the eight-year-old Beyoncé took in.

So Tina earned her global fame, and much of this, the third

studio album of her “second” career, caters to the global market with a

practised expertise which makes the Madonna and Whitney of that period sound jejeune (as I am sure was the

intention). Still, she could hardly be said to be happy; in song after song

(the titles speak for themselves) her voice tears through the bland music (the

panpipe keyboards dotted throughout are particularly irritating) with hurt,

rage and sometimes (the ending of “Be Tender With Me Baby,” with just an

acoustic guitar to cushion her) blood, as if she is fighting against the

eighties, wanting to smash the affluent glass ceiling. One is continually

reminded who might be on her mind while she sings these songs.

She is markedly happier away from the Albert Hammond/Holly

Knight/etc. Hits 4U machine (“The Best,” a cover of a song first recorded the

year before by Bonnie Tyler, is for me far too redolent of bad MBA seminars to

work – David Brent was only confirming what some of us already knew – although

for co-writer Mike Chapman it must have been the biggest payday of his career)

and working with Tony Joe White (his friend Mark Knopfler got him the gig).

With four songs on the album, including the patiently melancholy title track,

this represented a major revival in White’s career – the swamp man was never

going to go disco – and Tina sounds far more relaxed and involved. “Steamy

Windows” is sensual without having to have it underlined; her vocal performance

on “Undercover Agent” is a masterclass in using the voice to act out a story,

with its multiple pauses, slurs, squeals, hisses and scatting, all of which are

as carefully placed as any of Nicholson Baker’s commas. “You Know Who…” is

nicely modernistic (only Tina could sing “devastated MEEEEEE!!”), and the

closing title song, with Knopfler providing his best guitar work in several

years, is superficially fast but hugely slow-paced in its central resigned

lament, which concludes with a devilish cackle from the singer to fadeout.

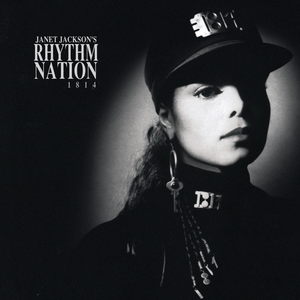

It’s just that this also came out that week, and peaked at

number four, beneath Tina, the Eurythmics and Gloria Estefan (have we said that

TPL 1989 is essentially the women’s

story?):

I think Rhythm Nation represents the point where I finally lost faith in the music press, British or American. It had a deadingly indifferent critical reception and you may search the end-of-year critics’ polls for it in vain – it only appears in Christgau’s list. A lot of alleged critics yawned in a it’s-not-1986-anymore manner – as though titans like The Wonder Stuff and Mega City 4 were up to the minute – but really it taught me that the primary function of music “criticism” was to big up your friends and your old favourites, and that the big-uppers were predominantly, and suffocatingly, male and white.

I think Rhythm Nation represents the point where I finally lost faith in the music press, British or American. It had a deadingly indifferent critical reception and you may search the end-of-year critics’ polls for it in vain – it only appears in Christgau’s list. A lot of alleged critics yawned in a it’s-not-1986-anymore manner – as though titans like The Wonder Stuff and Mega City 4 were up to the minute – but really it taught me that the primary function of music “criticism” was to big up your friends and your old favourites, and that the big-uppers were predominantly, and suffocatingly, male and white.

Because Rhythm Nation

was the year’s best and deepest pop record. As soon as the martial crunch-down

supersedes the abstract electronic miasma and launches into the titanic title

track you are immediately roused to get up and dance, or at least shake a fist,

in the same way that the opening credits sequence of Do The Right Thing dares you to stay seated (still one of the most

exhilarating cinematic experiences of my life, watching that on opening night

at the Ritzy in Brixton with its predominantly black audience, all rising up to

dance to “Fight The Power,” arguing back with the actors all the way through

the movie, generating internal debates). P-Funk, yes, a Sly Stone sample, yes –

thank you falettin’ Janet be herself again - but absolutely, overwhelmingly and

triumphantly 1989 now as in, well,

“The Star-Spangled Banner” was written in 1814 (hence the album’s subtitle) but

175 years later our people need a new

anthem of faith.

The album bustles along as exhilaratingly as anything on Def

Jam or Alternative Tentacles at the time, songs linked by random TV scans or

gnomic pronouncements (“Ain’t no acid in this house”), songs of jubilant

protest, demanding change and newness. Halfway through side one, following

songs about education, homelessness and drug addiction, Janet asks whether we

got the point – A&M wanted her to do an album called Scandal about her personal life but Janet, and indeed Jam and

Lewis, had other ideas and stood firm – says good, and invites us to dance. Yet

“Miss You Much”’s underlying drone still creates an ambience of doom, as if

already mourning something lost.

There are few more sheerly euphoric moments in eighties pop

than the long, multi-armed snake procession of “Love Will Never Do (Without

You)” which also, however, carries an air of triumph, of unstoppability, as if

the I is going to become the We whether you smug fuckers like it or not; the

creation of a new society. Buried deep in its mix is a dinner party guest from

the sixties, Herb Alpert. And yet this celebration comes to the deadliest of

halts at the end of side one to usher in the clearly deeply-felt “Livin’ In A

World (They Didn’t Make),” which culminates in the voice of a newsreader grimly

informing us of the Stockton playground massacre and reminds us of the

innumerable mountains still (in 2015) to be climbed and overcome. And running

like a scared spine through the song’s centre is Janet’s sudden cry, twice

repeated, in the same key and at the same

tempo, of “Save the babies! Save the babies!”

Side two is half hard dancefloor, half slow jams, but throw

a similar description at A Love Supreme

and see how inadequate that is. “Alright” hammers its defiant sticks like

Neubauten pop celery. “Escapade” – apparently originally inspired by Martha and

the Vandellas’ “Nowhere To Run” (see for parallel purposes N.W.A.’s “100 Miles

And Runnin’” from one year later) – is Prince worthy of Prince (or at the very

least Sheila E). “Black Cat” rocks “Beat It” right out of the aeroplane door

(kudos to Loud Heavy Rock Metal guitarist Dave Barry).

But the slow jams are the record’s slowly but intently

beating heart, and are not really three songs as such but one song in three

movements. “Lonely” lowers the lights and tempo and the record settles down to

regain its breath – we are reminded that Janet was as inspired by Joni Mitchell

and Tracy Chapman as Sly when it came to making this record.

But then “Come Back To Me,” one of Then Play Long’s greatest ballads, up there with “All Of My Heart,” “When Two Worlds Drift Apart” and “This Woman’s Work,” and a song which over a

quarter of a century later does not fail to engage or move me. Like Paul

O’Grady and Cilla’s “Alfie,” this gets me every time. It sounds like the end of

everything, not just a “foreign affair.”

Why does the song move me so? It is difficult to listen to

at this time of the year and normally it is one of these pieces of music which

I keep fenced off for emotional overload reasons. But I think its sadness is

more deeply rooted, because it is the one song on the record where she sounds like her brother – her

brother in the mid-seventies, that is, the way he used to sound before fame, the world and life did things to him…and maybe it is that Michael whose return she is begging, the same Michael who in 1989

was so high up in the world that he was unreachable. It already feels like a

premature requiem, building up melodically in ways not dissimilar to “Human”

before slowly disintegrating into the same hanging F minor seventh chord which

closes “Dreams”; the saddest chord in all of pop.

But, without any fuss, there then comes a happy ending,

another Motown reference – “Someday we’ll be together…well, tonight is that

‘someday’ – and it is with “Someday Is Tonight” that Janet tries to channel the

spirit of Marvin Gaye; hers is a brilliant performance, easily worthy of side

one of Let’s Get It On (“If I Should

Die Tonight” etc.), with her entirely satisfied murmurs and breathing settling

to something approaching…utopia (meanwhile, a muted Herb Alpert returns to do a

pretty mean Miles, and at the fadeout we hear a riff - can it be? - "West, End, Girls"...remember, we're all one...).

However, there is one last drone of warning – the ghost of

“Livin’ In A World” (just as the ghost of “Come Back To Me” flutters briefly

across the closing moments of side one, as if each side were a ghost of the

other) returns as Janet gives the following warning:

“In complete darkness we are all the same.

It is only our knowledge and wisdom that separate us.

Don't let your eyes deceive you.”

If you have to credit What’s

Going On? and To Pimp A Butterfly

– and you must - Janet Jackson’s Rhythm Nation

1814 is the midwife.