(#33: 2 February 1963, 14 weeks)

Track listing: Seven Days To A Holiday/Summer Holiday/Let Us Take You For A Ride/Les Girls/Round And Round/Foot Tapper/Stranger In Town/Orlando’s Mime/Bachelor Boy/A Swingin’ Affair/Really Waltzing/All At Once/Dancing Shoes/Yugoslav Wedding/The Next Time/Big News

“I stumbled out with my bundles. I smiled. Everybody smiled. The snow was a huge joke, and our predicament that of Alpine climbers marooned in a cartoon.”

(Plath, “Snow Blitz,” January 1963)

Setting both biography and hindsight aside – for now – “Snow Blitz” is a lively, exasperated portrait of a Britain starving for change, a Britain still marooned in the post-war cartoon of making do and mending, a Britain whose citizens muck on by as amiably and incompetently as they have ever done, their boots frozen to a lackadaisical lake of “can’t do.” A monochromatic Britain guiltily hungry for colour and life.

Set this next to the eager, Technicolor, world-embracing “Can Do!” of Cliff and his fellow jolly bus engineers and it’s easy to see how Summer Holiday, both the film and its music, enraptured and captured its willing audience; indeed, one can already see how Cliff’s idea of free enterprise made most of his audience keen for Thatcherism a generation down the line. The British winter of 1963 was an especially wretched one, and the new phenomenon of inexpensive foreign holiday travel – escape from winter, shiny, yellow refuge from all that we know - was hugely inviting. So it’s instructive to remember just how popular and even empathetic Summer Holiday was through these grimmest of times.

As in The Young Ones, Cliff is avid, up for it but always with a cocky eye set towards future balance sheets. His Indian background does, I feel, come into major play in this movie; the album cover, both in terms of typography and photography, suggests a strayed Bollywood picture, and I sense none-too-distant links with Slumdog Millionaire, although Cliff & Co.’s adventures are strictly for laughs, any underlying dirt as scrupulously scrubbed out as ever. He decides to customise an about-to-become-disused Number 9 London bus (remember that number as this tale approaches the other end of the sixties) and take it across Europe, not simply for the pleasure of it but to test whether the idea would work on a larger, profitable scale. Before he reaches the Acropolis he has to deal with gender bending, reluctant American child stars, scheming mothers and agents, petty crime framing, Ron Moody, and sundry mishaps in various stages of national dress – is this Lynch’s Wild At Heart I see far beyond me? – but all, inevitably and invariably, ends well; his future is mapped out and is clearly going to be a happy one.

“Summer Holiday” the song remains as daftly optimistic as anything to come out of early sixties Britain, a shimmering stroll through a future that everyone seemed to deserve, though its writers Bruce Welch and Brian Bennett are careful to retain some sense of ambiguity within its cheery hopefulness; the double bluff, for instance, of “We’ve seen it in the movies/Now let’s see if it’s true” (although we are in fact watching a movie) and the suggestion of long-term rain in the pizzicato string lines drizzling over Hank’s solo. Also, note the vaguely ominous vibes/piano figure which briefly jousts with Cliff’s carefree humming at fadeout before withering in amicable defeat.

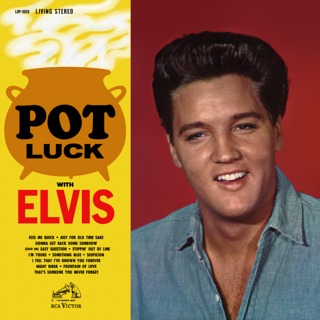

The soundtrack as a whole sums up much of what this tale has told thus far, which is fitting as it does mark the literal end of an era; many of the songs remain tailored to the still viable notion of All Round Entertainment set up with The Duke Wore Jeans and follow the classic pattern of film musicals which has formed the dominant voice in this tale to date, whether Rodgers and Hammerstein or Presley and Richard. There is even a song entitled “A Swingin’ Affair,” a leisurely vibes/flute-pedalled affair in which Cliff – assisted by Grazina Frame, back to dub juvenile lead Lauri Peters’ singing voice - does his best to be Sinatra, though his “a ring-a-ding-ding” is unlikely to awaken or arouse any grandmothers and, as with the album in general, he does his best to avoid matters inconvenient or explicit: “We’ll enjoy the music,” he and Frame sing, “but we won’t fall in love.”

Otherwise, it’s Mickey Rooney time again; “Seven Days To A Holiday” sees Cliff excitedly urging his co-workers to turn the bus into a fountain of red magic (“We will check everywhere/Though it’s hard to get there”; “Cor blimey, what a shower!”). The unlikely “Let Us Take You For A Ride” alternates between a slow, bass clarinet-driven crawl of a swing in which Cliff explains in painstaking technical detail (deconstruction!) to Una Stubbs’ girl group exactly why their car won’t start and an explosion of brisk cantering as Cliff pleads with them to board their bus. “There’s no need to look terrified,” he rather startlingly chuckles at one point.

There are also travel-oriented setpieces and ballads; “Really Waltzing” is an extraordinary piece of meta-Strauss self-commentary in which a baffled Cliff, seventeen years ahead of David Byrne, wonders exactly how he got here (“How did I get so square?”). “I know this kind of music makes me sick and you sick,” he remarks. “Still, I’m aware.” It’s a telling comment and one which could frequently be used against some of the things he went on to do (not least “Really Waltzing” itself, which ends up being hijacked by two Mike Sammes Singers bearing terrible German accents and rhyming “houses” with “cowses”). The waltz then speeds up and the original (unfilmed) ending of the “Dance Of The Dead” episode of The Prisoner comes instantly to mind.

The ballads tread a faintly treacherous path between schmaltz and truth. “Stranger In Town” wanders inoffensively (“Every girl is a beautiful girl when you’re a stranger in town” etc.) before veering off, via a segment of whistling backed by Deadwood Stage woodblocks, into a series of orchestral pastiches staggering from the Danube to Dixieland. Cliff’s good vocal on “All At Once” is offset, not to say drowned, by gruellingly dolorous 101 Strings lines and a melancholy muted trombone solo (probably Don Lusher). Set against this, “The Next Time” is a finely regretful, beautifully timed country-tinged performance fuelled by Hank’s chunky piano block chords – as always, Cliff seems far more himself when the Shadows are with him – and we’ll come back to the question of Cliff losing sleep in due course as this tale lengthens out. “Bachelor Boy” has since gained some notoriety, not least in part to its predicating, in tune, tempo and arrangement, “You’ve Got To Hide Your Love Away,” but seems less of a closeted closet admission and more of the most reluctant pro-laddism song ever written (Cliff co-wrote it with Welch) since he’s happy to be a free and untethered youth until he finally settles down and has A Wife and A Child.

It is the Shadows-led rockers which point the brightest way over the bridge that this album forms, especially the trio of Shads instrumentals on side one. “Les Girls” bears a hardness to its swing and guitar cut-and-thrust which most readily anticipates Liverpool, complete with an exhilarating mid-section where Bennett’s drums explode, and a concluding series of trapdoors of successive key changes. “Round And Round” (which ends very abruptly) and “Foot Tapper” (a different version to the chart-topping 45, in a lower key and with a fadeout rather than an ending) maintain the momentum, and again Bennett’s drumming seems markedly predominant.

Finally Cliff and the Shads prepare to rock, though there are already signs of rebellion; the nursery rhyme-engineered “Dancing Shoes” is scarred by Hank’s repeated jagged dissonant snarls (and his raspberry of a tongue-sticking-out introduction). However, as the film ends and Cliff gets both marriage and business proposals, “Big News” slides like a happier variant on “His Latest Flame” (thanks, Lena). “I want to make a statement!” proclaims Cliff (his third co-composer credit on the album). “I’ve found a plan for living!” The tickertape parade fades out and closes this section of our tale, though both Stanley Black orchestral interludes deserve brief mention; in particular “Yugoslav Wedding”’s string and brass figures directly predict the Overture to The Lexicon Of Love, and the piece’s varispeed in-and-out-of-dissonance trundle must surely have been an influence on the younger AR Rahman. Just as Slumdog Millionaire concludes with an exultantly triumphant dance in a train station, so does Summer Holiday end with a modestly victorious bop around a bus. Life, meanwhile, will trundle on, providing its subjects with a lesser or different future than they might have expected. In January 1963 General de Gaulle vetoed Britain ’s entry into the Common Market; and as for idyllic travel, March 1963 saw Beeching’s marathon closing of less than profitable railway branch lines. And then there was Profumo. Britain ’s bus services would eventually become denationalised and opened out to competition to the detriment of all concerned except shareholders; this was Cliff’s idea made cold rationalist reality. And then there was the collapse, and a 2009 London as incapable of dealing with snowfalls as the 1963 London, and constrained Britons forsaking expensive holiday travel for more local comforts. The film's director Peter Yates would in time consider fast moving cars as a substitute for friendly-faced buses. In the context of this tale, a new chapter is about to begin, and Plath would not survive the winter to see it or live through it. But the cheer was as unquenchable as ever, and we were very careful not to burn any bridges, particularly those down which we might have to backtrack in any future.

“Oddly enough, no one really beefed…The cheer seemed universal. We were all mucking in together, as in the Blitz."

(Plath, ibid.)

.jpg)