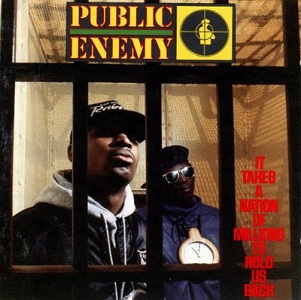

(#368: 2 July 1988, 3 weeks)

Track Listing: Talkin’ Bout A Revolution/Fast Car/Across The Lines/Behind The Wall/Baby Can I Hold You/Mountains O’ Things/She’s Got Her Ticket/Why?/For My Lover/If Not Now.../For You

“Few of us sufficiently recognise the importance of courage in the life of the imagination, and that it can make us free from fear and open to the fullness of reality.” – Max Harrison, The Wire, December 1986/January 1987

...and so spring has come, I’m still at Ryerson, condolences are given to me without much response on my part – my grief is private, my urges are to experience the new. The world has blown down a door, a whole wall, and I am spending my time adjusting, ever so slowly, to this new view. I help to choose the music for the memorial at Sheridan College but don’t attend (just as I didn’t attend my father’s funeral as my mom didn’t go either); I manage, come May, to pass all my courses and move on to the next and final year. Music means everything and nothing, is either great or terrible, it either somehow touches me or it does not. My chronology for this year is badly damaged and in this and other posts for ’88 I am not going to write about albums in their “proper” order. I don’t even recall buying that much in the first half of the year, save for ordering Sgt. Pepper Knew My Father from the NME, which I listened to incessantly, as I did their other tapes from around this time, Indie City 1 & 2. Instead I was caught, quite unawares, by poetry; the PBS station in Buffalo (channel 17) had shown the original run of Voices & Visions in ’87 and their modest sister station (channel 23) was showing it in reruns in the spring of ’88. By chance one night (May 12th to be precise) I turned it on and there it was, a whole show about Robert Lowell. I liked it, and tuned in the following week for a show on someone I didn’t know called Sylvia Plath.

Well.

I don’t think there was another viewer more primed and ready to dive head-first into Plath’s life and work than me, and before long I was reading what I could get and I think I even got a tape or two of her reading her own work as well; this was a life and a language that I could understand. I suddenly had a new standard in music – poetry – and plainspoken American poetry, at that. I didn’t regard her extreme and intense life as odd, as being a “half-orphan” (as the government officially regarded me) already made me different from 99.9% of my fellow students at Ryerson. I felt akin to her, without being much like her – she a Yankee, me a Californian – and I became more open to poetry in general, to the arts, to (big breath here) life itself. At some point in late May I visited Washington D.C. with my mom to stay with my godmother Genie; and then in June, the Journalist himself visited us in Oakville while staying with his parents on his own little break. My mom called him, not unkindly afterwards a “roundhead” and he wrote down a bunch of radio shows to listen to in London, and a place to eat that was cheap – we got along fine, and my mom regarded him favourably as she could tell he was not at all the sort of guy who would invite me to some illegal rave somewhere, give me Ecstasy, or anything like that. He was (and presumably still is) about as square as a broadcaster could be, and thus by early July I got my hostel association membership, booked my room, and looked forward to my visit. A few days beforehand my mom gave me Plath’s Collected Poems in paperback, and I took it and my Walkman with a copy of Indie Top 20 Vol. 4 and who knows what else – clothing, shoes, Woolite, a pen, a day planner, my Frommer’s Guide etc. I was ready to meet whatever fate I was going to meet, all the while wishing I had already been in London....

....and here is where my chronology begins to warp. I know very well Rank was released in the fall of ’88, but it had already happened in 1986; the concert, I mean, in London’s still-not-all-that-fashionable Kilburn area. The Smiths are dead; long live the The Smiths. Their end came around the time my father started to lose his memory, started just as that slow catastrophe was starting, and Morrissey’s solo single and then album in the spring of ’88 didn’t move me that much. He seemed to be forever skirting around something without ever pointing to it, and I already lived somewhere where every day was like Sunday already, though it seemed so impermeable that the idea of a bomb or strange dust was unthinkable, unimaginable. For me it was as if Morrissey was too come-hither but wasn’t really going anywhere or hithering to an actual solid feeling. Whereas Rank shows The Smiths at their acme - fierce, playful, digging into the music and being passionate - with Rank there is no holding back. Morrissey grunts and growls and the words sometimes sound as if he is not just singing but having a violent physical reaction, as if he has been waiting his whole life to do this one thing, and here he is and he is tossed and turned by the music, sad and angry and funny alternately, and there is no encore because there is nothing left to give. This is the concert I never got to go to, so it’s not nostalgia for me to praise it, even though it might come off that way.

At the same time, even then it felt like an echo of a previous age, a time when things were different, when I was waiting to see if Ryerson would accept me, when my own writing ambitions were nebulous, before the fall of ‘87/winter of ’88 formed me, more or less, into the young woman I was. I didn’t have much of an idea about that – my ambition to write – especially as poetry made my language alter, just as learning French had changed my English. A career in straight-up journalism where I interviewed, shaped a piece, tried to be neutral – was not for me. I could hardly be neutral about anything. At best I could be diplomatic, persuasive, but I had no outlet for that, my journal and my mom being the two outlets where I could talk about music (I didn’t write that many letters to the Journalist). I knew I was too opinionated and naive to write about music just yet, but somehow I didn’t think even too much about that. (I was wholly inspired by all the fine writing about music I’d encountered and never saw myself as “in opposition” to any of it.)

What with my mind being taken up with packing, getting new dresses, keeping a sharper ear than usual on the UK news, and wondering (besides the few errands my mom sent me on, to do with her craft jewelry business) what I would do when I got there. I had no idea. Into such a void all kinds of things can happen, and while I am loathe to write too much about the London I found in the summer of ’88, (which will be discussed in the next piece) I can say that I wasn’t thinking about finding anyone in any way, that I didn’t consider that I would be walking the same streets, taking the same Underground, sweltering in the same heat, as anyone who could at all become important to me, besides the Journalist himself. I wasn’t even thinking that “Plath had found her guy in the UK, and so would I” - even as I nestled my copy of her Collected Poems in my bag. I know that I was intense – moody, you might say – due to grief; impatient, numb to everything at times, feeling everything at full force at all times. An inner gear had changed. My aesthetics were changing too, or maybe just being sharpened.

Thus, The Fall’s I Am Kurious Oranj is another step back and forth – performed in London before I arrived, and yet not released as an album until October. It hovers over this trip to London and my time there and after like fog. Never mind that it is about someone from the Netherlands (my last name is Dutch, more accurately Frisian) coming to London and taking over. It seems to be about the band itself, about music, about the then Thatcher government – all done live, with Michael Clark’s dancers, the songs just as intense as those on Rank, maybe even moreso? I never got to see this either, so while those who did enjoyed it don’t find the music apocalyptic, I do – something is ending here, or starting – hard to tell. All music sounded final, terminal to me, raw, at least that could break through my scepticism, my need for the direct and actual. The Fall are as sharp as possible here, the one-two punch of “Big New Prinz” and “Overture From ‘I Am Kurious Oranj’” making the stage-in-my-mind as big and dramatic as possible. I always liked The Fall before, even when, admittedly, I wasn’t exactly sure what the heck Mark E. Smith was talking about – but here there’s a focus, something of a coherent story, and (to use a word I used back then) it was indeed (as is) a boss album. The songs suit movement, slow and fast; there is real pathos in “Van Plague?” and sorrow in “Bad News Girl” but the moment it all comes together is their version of “Jerusalem.”

I have heard joyous/dutiful choirs and crowds sing this before and since, but what can they bring besides the crushing realism of The Fall’s version? It begins a lot like The Smiths' “The Queen Is Dead” only slower, the bass singing the song, and then the bare bones of the melody – “Da Dum Da Da, Da Dum Dah Dah” – over and over, as Smith more or less recites the poem by Blake (how could I not love this album – it’s got poetry in it!) and then the pause...as Smith talks about slipping on a banana skin and not getting anything from the government and being “very....disappointed.” As if to say, you people, this is what Blake wanted and you just want (or will settle for) compensation. “It was the government’s fault” the banana skin was there, he says, but as the music speeds up he gets back to the heart of Blake’s poem – “bring me my bow of burning gold/bring me arrows of desire/ my spear, o clouds unfold” and then “and though I rest from MENTAL FIGHT/I will not rest until Jerusalem/is built in this greenanpleasantland” – and that phrase returns like an itch that cannot be scratched – “It was the fault...of the government” as the band goes full-tilt, as the many faults of the government seem to –well, to me – parade by. “Jerusalem! Jeru..salem” Smith sings in between, the green and pleasant land that is the myth of what some think already exists far away from what Blake is talking about – the “dark satanic mills” being the ugliness of Thatcher’s Britain, as much a mindset as anything directly visible or audible. To hear a poem/hymn done like this was liberating, enlightening, not so much making something new as taking something old and showing that it wasn’t really all that old, after all. An event like William of Orange being invited to take over the British throne was a moment for a nation that was struggling to deal the IRA, with the seemingly endless Thatcher government and its policies (including the by-now law of Section 28) and The Fall seized on it and made it make sense to me, a mere visitor. The unreality of my life – my unwanted but fresh new life – was made more unreal by going to London, and I realize that there is a bigger-than-life quality to this music that must have made up for the grubby realities I was faced with, all the time...

But, again, I must emphasize that even with the Journalist I had no hopes; I wasn’t going to London thinking anything would happen and yet...I read up on I Am Kurious Oranj and where were the live parts of it recorded?....somehow I was being propelled “slowly slowly” as Smith sings in “Cab It Up!” into the future, so slowly there was no way I could suspect it myself.

Now, I must mention that this next album I bought in London, and no, I don’t know why either, as it had been available where I was since April, but...being so attuned to the UK press and release schedule, I dutifully read the NME interview with Public Enemy in the early summer of ’88 and then got it in London at (I think) a Virgin Megastore, possibly the one on Tottenham Court Road. (Cue wistful sighs from those who wish any kind of music store was there now.)

It wasn’t like I didn’t know them – I had a tape of Yo! Bum Rush The Show after all – but something in me must have sensed that getting It Takes A Nation Of Millions To Hold Us Back in London was somehow the right thing to do. I do not recall the person at the counter giving me any kind of “you don’t look like the kind of person who buys this sort of thing” look. Maybe I had already given myself away as an American and well of course I would buy this, they’re Americans too, after all. But then there’s the act of buying an album, and the act of listening to it. I put it in my Walkman, pressed play, and waited...

...

....

...somewhere between that pause and the noise, the eager anticipatory noise of the crowd, it is likely that nothing happened. What I could not know – did not know – for a long time was that I had just crossed over a metaphorical bridge, from there to here, and that from here my future began. I am going to slow down now and give you (in case you haven’t heard it) the full introduction...

“Hammersmith Odeon, are you ready for the Def Jam Tour? Let me hear you make some noise!”

(crowd noise, growing, makes obligatory noise)

“In concert for BBC Television tonight and a fresh start to the week (referring directly to his own show, though I didn't know that at the time), let me hear you make some noise for PUBLIC ENEMY!”

Air raid siren starts...

“PEACE! Armageddon has been in effect - go get a late pass – step.”

Air raid siren continues...

“This time around the revolution will not be televised – step.”

Air raid siren continues ...

“London England...consider yourselves...warned!”

So said Professor Griff in early November of 1987, right there in the city where I walked and sweated and searched in near vain for something to sustain me and it was right there, right there in my Walkman, right as I took a damn break at the yeah-you’d –think-they’d-bring-it-back-now-huh Harrod’s Health bar, where I got my expensive fresh orange juice and sat and looked at the lyrics and credits and could only wonder at what the hell was happening. I had no time to listen to the radio with this on my hands, and it was just as well, as (from what I gather) hardly anyone actually played anything from it, unless they had to**. This nice young woman from nowhere had stumbled into the avant garde practically without even trying. It was not so much a conversion experience as something more intense. It was as direct as that thirst-quenching juice, but how many loved PE as I did instantly in London? What else could give me the courage to express myself? Plath was good, but her example was not one to follow the whole way. I couldn’t be PE either, obviously, but the freedom the album gives the listener is important, that courage Harrison mentions here, that opens the window and inhales...

...while Simon Reynolds might call this band and album “domineering” I just hear the actual YELP that goes back to Whitman, that rhymes (poetry again!) and samples and is damn close to being jazz at times (“Jazz is the umbrella under which all other musics stand” says Sonny Rollins). I can only pity the UK music writers who didn’t get that connection, that PE were going back (in spirit if not actuality) to the Last Poets, Miles Davis, Archie Shepp, John Coltrane (more later), Charles Mingus, Max Roach...and with their willingness to make pure noise that makes sense/nonsense, they weren’t that far (for me) from The Fall, even. Reynolds can talk about hip-hop being “heartless” but what is Chuck D but a big beating heart trying desperately to get something across? And unlike Morrissey, he actually has a point – he is louder than a bomb.

...if someone had sat down next to me at Harrod’s Health bar and looked over and told me, kindly, that there was someone else also going around London also listening to this and further back, he was actually there at the Hammersmith Odeon (I had no idea, despite having an A-Z, where that was) making the noise Dave Pearce was requesting, well, what could I have thought? It is just as well this didn’t happen, as how could I have believed it*?

The heck, I didn’t even know it was Dave Pearce, let alone have a sense of providence that this, this was the key to so much, that after hearing it I wasn’t going to be the same, just as after watching the show on Plath I wasn’t the same. I was far, far away from the studious music writer who would listen carefully and make notes and so on. I was immersed, in some kind of new world, a world of both this and The Fall and The Smiths and the Wedding Present (I joked I just wanted to go to London to get a tape of George Best)... a world where so many bullshit notions of being on this side or that side of music wars or theories or God knows what made no sense whatsoever. Nation of Millions isn’t an album that I can talk about normally, because of the extraordinary way it promised something to me, waking me up with an actual air raid siren, as if only now was something truly remarkable going to happen, but I had to stay awake, alert.

And the first thing was to find my voice, the voice that had been stifled up in my room, my journal – and the trip to London was the first BIG step in that. I knew I had to have that voice in order to even deal with the idea of that other person, let alone the actual other person...I was too much of a mess to even deal with myself most days, let alone meet anyone important, and getting to know this music was the main thing, beyond the basic necessities of life...it’s not an easy-going album, but then I wasn’t really an easy-going person. The rhetoric of Chuck D was something I enjoyed as sheer language and message, and I didn’t regard hip hop as “paranoid schizophrenic” – which is Reynolds’ idea of the male ego at its extreme. What if your song was on the radio and then the DJ said “I promise you, no more music from the suckers”? PE aren’t so much paranoid (I’ve always heard “Black Steel In The Hour Of Chaos” as being about emancipating yourself from mental slavery, as Marley sang) as assertive, telling their side of the story, because not everyone in the music/media world liked them, or would even talk to them, and if a prominent DJ called them suckers repeatedly on the air, well, what to do, how to respond? I was quickly learning that as much as I liked reading the UK music press, there was something amiss in it; too much wafting away on this theory or that, not enough solid consideration of where this music, literally and figuratively, was coming from***.

And the first thing was to find my voice, the voice that had been stifled up in my room, my journal – and the trip to London was the first BIG step in that. I knew I had to have that voice in order to even deal with the idea of that other person, let alone the actual other person...I was too much of a mess to even deal with myself most days, let alone meet anyone important, and getting to know this music was the main thing, beyond the basic necessities of life...it’s not an easy-going album, but then I wasn’t really an easy-going person. The rhetoric of Chuck D was something I enjoyed as sheer language and message, and I didn’t regard hip hop as “paranoid schizophrenic” – which is Reynolds’ idea of the male ego at its extreme. What if your song was on the radio and then the DJ said “I promise you, no more music from the suckers”? PE aren’t so much paranoid (I’ve always heard “Black Steel In The Hour Of Chaos” as being about emancipating yourself from mental slavery, as Marley sang) as assertive, telling their side of the story, because not everyone in the music/media world liked them, or would even talk to them, and if a prominent DJ called them suckers repeatedly on the air, well, what to do, how to respond? I was quickly learning that as much as I liked reading the UK music press, there was something amiss in it; too much wafting away on this theory or that, not enough solid consideration of where this music, literally and figuratively, was coming from***.

The sheer density of the songs ("Night Of The Living Bassheads" being my best example) meant that the still-used-by-some-broadcasters term "talking over records" is just plain wrong. It's more a sound collage, with the records, as such, doing the talking as much as Chuck D or Flavor Flav. That they sample themselves from their first album just shows how they are beginning with themselves to set up a whole new way of thinking about and creating music - this is a loud album and was recorded with the sound needles going over into the red (usually something no producer would do, but this is rap with a rock attitude). The folks at Def Jam, Rick Rubin included, weren't allowed in the studio, and had to trust Hank Shocklee and the Bomb Squad knew what they were doing, which of course they did.

One last thing - when Chuck D mentions John Coltrane in "Don't Believe The Hype" (I can only wonder what Alice Coltrane made of this) he says "writers treat me like Coltrane, insane/yes to them but to me we're a different kind/we're brothers of the same mind, unblind/caught in the middle and not surrendering." I will be talking a lot more about John Coltrane and his supposed insanity in future TPL posts, but it's nice for Chuck D to note that before there was hip hop offending and confounding writers, there was jazz - not just anything, but something called "The New Thing" (a term that came from either Impulse! Records or LeRoi Jones). Hip hop was the new thing now, and not everyone was ready, willing or even able to understand it. But it made perfect sense to me, as I walked the streets of London..."Mandela, cell dweller, Thatcher you can tell her make way for the prophets of rage..."

Oh, I could go on about It Takes A Nation Of Millions To Hold Us Back - a title that Chuck D noticed a Toronto paper used as a headline for an article about his band, a line from "Raise The Roof" - you see how self-contained and yet somehow expansive this album is? Okay....

By the time I got to London, Tracy Chapman was on the cover of Melody Maker (I think) and had become famous overnight for her appearance at the Mandela concert in mid-June; in a few months time (late September) I would see her as part of the Amnesty International Human Rights Now! tour in Toronto. I was so preoccupied by Indie Top 20 Vol. 4 and Public Enemy at the time that I didn't get her album, but many did, and it is an interesting counterpoint to PE in that it's a solo female voice here, a young Tufts graduate who busked and wrote songs and didn't think she'd get a record deal, let alone one with Elektra, was a hit. Why? Were people a bit tired of the Reaganrock around them and wanted something simple and sincere and direct? Well, yes; and while PE were talking about kind of the same things, Chapman appealed to those who were fans of fellow Amnesty tourmates like Sting, Peter Gabriel and especially, I'd guess, Bruce Springsteen.

"Talkin' Bout A Revolution" is about the impatience of people but also their exhaustion - stuck in the unemployment line, waiting around for something good to happen - the "whisper" that revolution speaks in (the revolution here isn't going to be televised either), The poor are going to take what is theirs; but you better (and she sings this as if you really had better) "run run run run RUN" as revolutions tend to happen and end quickly, so you'd better be ready when it happens where you are. Hear the whisper once and then do what you need to do.

"Across The Lines" is about the dividing line between the whites and blacks in a town, and the town riots over the assault on a "little black girl" - boys on both sides get hurt, but most damningly, the girl is nameless but the town calms down collectively by deciding that "she's the one to blame." This may sound like a protest album from the 60s (I'm guessing this is what Elektra wanted) but already the tone is different, somehow...

"Behind The Wall" is a good example of this - an acapella ("rock the acapella G" as Flavor Flav puts it) about a husband abusing his wife - "domestic affairs" that the police say they can't do much about. Chapman hears and is an audio witness, but will she call the pollce anyway? More screaming, and then an ambulance; and then the police try to keep the peace, but not before. The song is stark, uncomfortable, and challenges you to wonder what you would do. Also, did "911 Is A Joke" come from this? What do you think?

"Baby Can I Hold You" is by far the most conventional song here (later covered by Neil Diamond and by Boyzone), in that it's one of romantic yearning, yearning for words of humility and true love - trust me, love means always having to say you are sorry, to ask to be forgiven, to profess that love again and again. The Other here has yet to learn this and you have to wonder at the patience of the narrator, who has had to put up with this for a long time, and has to sing this song to tell the Other to say "baby can I hold you tonight." It is a kind of bossy song that way, but love does mean being bossy at times, or at least decisive...

"Mountains O' Things" is a cold look at the cycle of wanting, having and then realizing that having things isn't really enough - that by "exploiting other human beings" you have lost your soul - that "mostly you are lonely" as the "good people" who have helped you are just your "stepping stones" and so forth. The narrator keeps his/her mountain o' things as a literal barrier against his/her enemies, and these things are consolations for having no friends and no soul. All those status symbols that rock and hip hop people are always going on about? Traps, says Chapman, even as her narrator thinks that they can actually take these things with them in "a grave that's deep and wide enough."

"Why?" is a stark song about just why is it that the world is so awful - "Why is a woman not still not safe when she's in her home" echoes "Behind The Wall" - and immediately reminded me of the episode of The Prisoner where a computer explodes once the simple question of "why?" is asked. Those who know don't speak above that whisper, but Chapman says that once "the blind remove their blinders/and the speechless speak the truth" the reason why will be explained. Well that's nice you might think, but who are these blind people, these quiet folk? Again, is this you, the listener?

"For My Lover" is a study, a profession, of insanity. You'll do what? Two weeks in a jail, twenty thousand dollars bail - what the hell is happening here? Why is the narrator doped and psychoanalyzed? The narrator seems to know that s/he is crazy, that s/he "follow(s) my heart/And leave my head to ponder" this, and wonders if all these sacrifices are worth it, if doing something/anything "for my lover" is really enough. "Deep in this love" is where s/he is though, and from that perspective, everything is worth it, including being jailed, possibly even considered by the straight world as crazy. The craziness of love wears off however, and the narrator is in the difficult place of having to decide whether suffering itself is a requirement of love, or not....

"She's Got Her Ticket" is about a girl who most certainly does know what she wants, and has not one ponderous moment to waste - "too much hatred corruption and greed" have repulsed her, and perhaps this is the girlfriend of the man who wants "mountains o' things" who has her ticket and is going to fly away. Is she a runaway, a failure, a drop out - again, this is how the straight world sees her, but she is setting her own agenda of escape, of freedom - anything is better than where she is now, and if she has "no roots to keep her strong" then she will have to be a pioneer and make her own. This is the happiest song on the album, in that the young woman is determined, optimistic, and has the sort of spirit that will see her prosper in her own "place in the sun."

"If Not Now" is a bit Morrissey, in that the song is gently downbeat like a Smiths song, all about how love must be grasped immediately, or else it somehow it's not real or free - that love not claimed in the moment is a denial of life itself. "We all must live our lives/always thinking/always feeling"....the feelings take over at the end, with "For You" admitting that language itself it not able to express "this feeling inside." With just her guitar, Chapman sings about how she loses her ability to speak once she looks into her heart, and it's Cordelia's song if it is anyone's, that intense feelings make you "no longer the master of my emotions" and thus the album ends, with literally no words left to say, no way to get across feelings...

I have left "Fast Car" for last as it is the most famous song from this album, and a song that has become a standard of sorts. It keeps popping up on the UK charts, usually when someone performs it on a tv show like Britain's Got Talent or X Factor, and it's the single that's covered, not the whole song. The single version of the song shows the ambition of the woman who wants a "ticket to anywhere" and the guy has the car and together she figures they can go places, literally and figuratively; when she's in the car with him, she gets the feeling that she can (the pathos of it) "be someone." The narrator says she has "nothing to prove" but then hatches a plan - she's going to get a job, save money, and then they can both go get jobs later in the city and prosper, so she can get away from her father (who has been abandoned by her mother; the song suggests she's tired of looking after him and is going to abandon him too). The single, however, doesn't take us to the crushing end of the song, wherein they do have that house in the suburbs that they want - and kids - and he goes out to the bar with his friends more than he sees her or their children.

The car isn't the subject here, but her being stuck - at first at home with her father, and now as a working mom in the suburbs who is neglected by her husband, who is told that he can "keep his fast car and keep on driving." Take it or leave it, this is where ambition and love collide, and the single version leaves you wondering if they will make it out there, and the album version gives the sorry truth that they do, but the fast car is no solution any more, but part of the problem, if anything. The constant longing to "be someone" is not answered by work, or where you live, or even having a fast car or knowing someone who does, though I suppose those all help; to the person who feels they don't belong, nothing can help (not even the modest mountain o' things the suburban life signifies). The song "She's Got Her Ticket" shows the woman who is free of such ideas, but the narrator of "Fast Car" wants a normal life and ends up being trapped by it, the slightly despairing melody of the song rising to some happiness with her in the car happy to be intoxicated by its speed, but then the sober reality of her life comes back to her once again...

The car isn't the subject here, but her being stuck - at first at home with her father, and now as a working mom in the suburbs who is neglected by her husband, who is told that he can "keep his fast car and keep on driving." Take it or leave it, this is where ambition and love collide, and the single version leaves you wondering if they will make it out there, and the album version gives the sorry truth that they do, but the fast car is no solution any more, but part of the problem, if anything. The constant longing to "be someone" is not answered by work, or where you live, or even having a fast car or knowing someone who does, though I suppose those all help; to the person who feels they don't belong, nothing can help (not even the modest mountain o' things the suburban life signifies). The song "She's Got Her Ticket" shows the woman who is free of such ideas, but the narrator of "Fast Car" wants a normal life and ends up being trapped by it, the slightly despairing melody of the song rising to some happiness with her in the car happy to be intoxicated by its speed, but then the sober reality of her life comes back to her once again...

Towards the end of the 80s there had to be a step back to something realistic, something crossing over from the blues or folk to pop, something connected to the world - something that would bridge the generations, a album of unquestionable goodness that whispers more than anything about how life is and how it could be, and the courage (that word again) necessary to make things change for the better. It also shows a generational shift, as Chapman is part of the (at this point, not yet named) Generation X; in 1988 she is only 25 and suddenly is a superstar folk singer, her album's lyrics (the one I have here on cd) translated into French, Spanish, German and Italian - so folksingers all over Europe can start singing these songs in their own languages. (It's nice to see this, and of course the ones in French look most romantic to me ["Pour Mon Amant" et "Pour Toi"] and the Spanish ones look the most revolutionary ["Hablando De Revolucion" y "Por Que?"]) It's a generation that is just starting to express itself, and I would say that it's the women of this generation who have the most to say; it feels awkward to call this a timeless album that could only have gone to the top at around the summer of '88 but so it is. So much of it deals with problems that are still with us, from greed and violence and racism to the more intimate problems of honesty and realizing that so many things aren't all they are cracked up to be.

And so I sit, kind of nervous, the night before I fly with my own ticket to London; I know I am not escaping from anything beyond a house that is now all too quiet, on a quiet cul-de-sac on a street where there isn't even a real sidewalk. I live next to a ravine full of wild creatures, yet can see my old high school from my bedroom window. I have to go, but have no real idea outside of my Frommer's Guide what to expect. Big things are going to happen, a whole new world awaits....

.....next on TPL - is music enough? Is writing about music ever enough?

*If this certain someone had told me later in ’88 that the same person was also in the audience for the concert parts of I Am Kurious Oranj (in Edinburgh in August) I would have had some kind of breakdown. Who is this person? It has to be a guy, right? I mean, the hell?

And yet this is actually true.

** John Peel didn't play any hip hop because he had a problem with its attitude towards women, but I would like to kindly point out that Russell Simmons signed Oran "Juice" Jones to Def Jam and his "The Rain" has to be one of the most mean songs about a woman ever recorded. Simmons didn't even like PE until they started to sell a lot of albums, which shows you how disliked PE were, even by their own label. I don't think Peel played "The Rain" either, but my point is all of music has a problem with its attitude towards women, not just hip hop.

***I’ve been quoting from “Hip Hop: The Minimal Self” In Blissed Out by Simon Reynolds (Serpent’s Tail, 1990). (Sigh, I try not to be in opposition to others, but a young woman’s got to make a stand now and then...)