(#326: 7 December 1985, 2 weeks; 4 January 1986, 2 weeks)

Track listing: One

Vision (Queen)/When A Heart Beats (Nik Kershaw)/A Good Heart (Feargal

Sharkey)/There Must Be An Angel (Playing With My Heart) (Eurythmics)/Alive And

Kicking (Simple Minds)/It’s Only Love (Bryan Adams & Tina Turner)/Empty

Rooms (Gary Moore)/Lavender (Marillion)/Nikita (Elton John)/Running Up That

Hill (A Deal With God) (Kate Bush)/Something About You (Level 42)/We Don’t Need

Another Hero (Thunderdome) (Tina Turner)/Don’t Break My Heart (UB40)/Separate Lives

(Phil Collins & Marilyn Martin)/She’s So Beautiful (Cliff Richard)/Election

Day (Arcadia)/I Got You Babe (UB40 [guest vocals: Chrissie Hynde])/Blue (Fine

Young Cannibals)/If I Was (Midge Ure)/Cities In Dust (Siouxsie and The

Banshees)/Uncle Sam (Madness)/Lost Weekend (Lloyd Cole & The

Commotions)/You Are My World (The Communards)/Just For Money (Paul Hardcastle)/Miami Vice Theme (Jan Hammer)/Body Rock

(Maria Vidal)/Tarzan Boy (Baltimora)/Body And Soul (Mai Tai)/Single Life

(Cameo)/Mated (Jaki Graham & David Grant)

“Of the same origin as the social process and ever and

again laced through by its traces, what seems to be strictly the motion of the

[musical] material itself moves in the same direction as does real society even

where neither knows anything of the other and where each combats the other.

Therefore the composer‘s struggle with the material is a struggle with society

precisely to the extent that society has migrated into the work, and as such

it is not pitted against the production as something purely external and

heteronomous, as against a consumer or an opponent.”

(Theodor W Adorno, Philosophy Of New Music, trans. Robert Hullot-Kentor. University of Minnesota Press; chapter 1, “Schoenberg and Progress,” section “Tendency of the Material,” pp 31-2)

(Theodor W Adorno, Philosophy Of New Music, trans. Robert Hullot-Kentor. University of Minnesota Press; chapter 1, “Schoenberg and Progress,” section “Tendency of the Material,” pp 31-2)

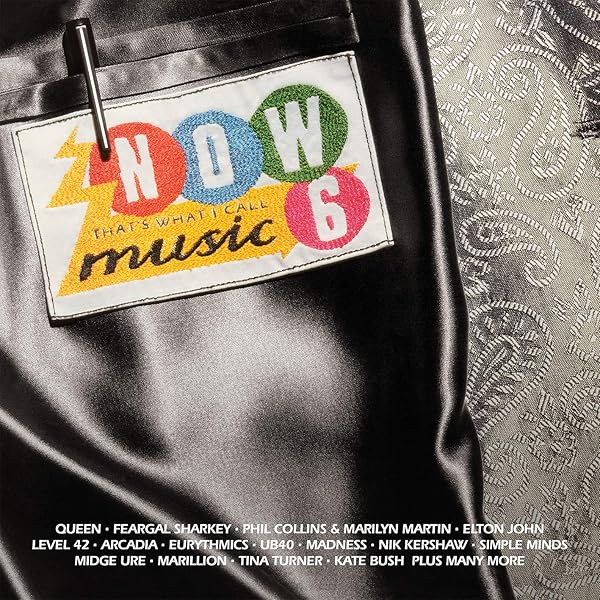

Now 6 Fact File

Title: Now That’s What I Call Music 6

Volume in series: 6

– in a series which was originally envisaged would not last beyond Volume 5 at

the very most and has recently reached Volume 88, the numerous branding

spinoffs notwithstanding.

Movements towards

brand development: Where Now were

always going to have the advantage over Hits.

The double LP edition of Now 6 comes

with inner sleeves which tell us that the preceding five volumes remain

available, complete with track listings, as well as informing us of two spinoff

collections. One will become #327, while the other was Now Dance, a collection of twenty 12-inch mixes. Those wondering

why Now 5 had to make do with “Magic

Touch” and “Get It On” will find the full-length, or at any rate extended,

versions of “Hangin’ On A String” and “Some Like It Hot” here.

Meanwhile, on the rear sleeve of the album itself, we

find the following message:

“YOU’VE HEARD THE RECORD. NOW READ THE BOOK!!

“YOU’VE HEARD THE RECORD. NOW READ THE BOOK!!

IMPRESS YOUR FRIENDS AND GENERALLY SHOW OFF WITH NOW THAT’S WHAT I CALL MUSIC MASTERMIND,

COMPILED BY PRODUCER [sic] ASHLEY ABRAM TO TEST YOUR MUSIC KNOWLEDGE. A STEAL

AT £2.99. AVAILABLE FROM VIRGIN SHOPS AND ALL GOOD BOOKSTORES.

BUY YOUR COPY NOW!

NOW LISTEN TO THE RECORD AGAIN!”

Provided that you were a music consumer in late 1985 who

didn’t object to being shouted at and ordered about as though you were a

Territorial Army cadet, there are now no Virgin shops from which to buy this

book, nor, do I suspect, does it retail on eBay or similar for anything

approaching £2.99. But it did the trick, whether or not you felt the trick was

worth doing.

Corresponding Hits fail: You may remember that

twelve months previously, Hits 1 won

out over Now 4. But in this return

match, Now triumphed again. Put to

one side any questions of rivalry – EMI and Virgin pointedly did not contribute

to The Greatest Hits Of 1985, and CBS

and WEA are absent from Now 6 – and it

is not a hard question to answer, the question being: why did Now 6 come top? I remember seeing Now 6 in the record shop when it came

out, and feeling somewhat…disappointed by the track listing. A lot of it I had

already, and there were no obvious curveballs.

However:

The Pig Factor:

The pig had been unceremoniously retired by the Now team; just as well, for the one depicted on the cover of Now 5 seemed ready to explode. The TV advertisement – again voiced by Tracey Ullman – suggested a new marketing shift

in the direction of abstract, mid-eighties, FACE/Blitz-friendly, slightly retro style. “FEEL

THE QUALITY,” commands the lower back cover in front of what is the lining of a

leather jacket. In other words, we at Now

are no longer dangling over the precipice of tacky.

Whereas:

Hits 3 didn’t really cut it. It wasn’t

that it was a bad compilation; just a tad unnecessary (was there anyone left in

late 1985 who wanted “Dancing In The Dark” and still didn’t have it?). It did

include the year’s biggest-selling single, Jennifer Rush’s “The Power Of Love”

(as well as Huey Lewis and the News’ namesake song), but just one other number

one (“Frankie”) which had already appeared on Now 5. Despite things like “Take On Me,” “Holding Out For A Hero”

and even a rare appearance on a TV-promoted compilation album by Madonna (“Dress

You Up”), the collection was rather lacking in chétif, and moreover was still recycling music from 1984; “Time

After Time” had been available for eighteen months on Now 3, and the Cars’ “Drive” makes a return appearance from Hits 1.

But Now 6 had four number ones, and a lot of other things

which mostly, at the time, you couldn’t get anywhere else (other than on the

parent albums). It looked and felt better. And maybe it had a better

story to tell.

Missing number

ones: Despite my previous remarks

about the near-comprehensive compiling of 1985 hits onto department

store-friendly albums, quite a lot was still missed out, and so I have to

report that five of 1985’s number one singles bypass Then Play Long altogether. The aforementioned “The Power Of Love”

is one, Shakin’ Stevens’ seasonal chart-topper “Merry Christmas Everyone” is

another, and the remaining three are ascribable to charity – USA For Africa’s “We

Are The World,” Bowie and Jagger’s “Dancing In The Street” and The Crowd’s

Bradford (and inadvertently Heysel) benefit disc “You’ll Never Walk Alone,” a worthy

effort which, thanks to the presence of at least one performer, will almost

certainly never be played on radio again. “I’m Your Man” appears on #328, while for “Saving All My Love For

You,” you’ll have to wait until #622.

Fried Chicken

The song appears on #331 (and for that matter on #439)

and it’s obvious that somebody (Freddie) had been listening to Frankie (the

group, not the song). The song itself is really nothing more than a celebration

of the bond between performer and audience, that although there is a stage

"we" are all in one place, with one common purpose. In their 1987

album Opus Dei, Laibach turned it into a scary fascist march. But its spirits, unlike

"Radio Ga-Ga" nearly two years before, are ultimately high and

friendly.

Nik Kershaw

“New music absorbs its antagonism to reality into its own

consciousness and into its own configuration.”

(Adorno, op. cit.,

p 96)

One major clue to the message this compilation may be

attempting to convey comes with what might be Nik Kershaw’s finest moment –

and, with typical predictability, his least successful Top 40 single, and indeed

the last Top 40 hit that he would have as a performer. In “When A Heart Beats,”

the anger which had been slowly and politely rising all the way through Human Racing and The Riddle finally boils over, and Kershaw calls for the entire

system to be pulled down. Threading his way through chord changes and time

lapses only a jazz musician would know – which was why Miles wanted him –

Kershaw uses his knowledge of harmony to construct about half a dozen melodic

and rhythmic trapdoors, all the while, from the introductory Goffin and King

(presumably via Billy Fury) paraphrase onwards, raging against blind

capitalism, the unfairness of fixed societal competition, and the blindfolds

worn by those who chose to revel in the fact that they were not the

unfortunates. His guitar solo is sonically and tonally askew to a degree which

must surely have influenced the aspiring teenage guitarist from Colchester (Kershaw’s

hometown) that was Graham Coxon. The song builds and builds in intensity until

something snaps – to be precise, Kershaw’s aghast wail at around 3:30. It is as

if he is saying “to hell with the lie of pop music,” and that was not the kind

of message shiny yellow late 1985 pop consumers were willing to hear. A

standalone album (on whose tape and CD versions “When A Heart Beats” was

belatedly added), 1986’s Radio Musicola,

is basically an extended rant against the beast of the music industry broken up

by parodic fifties-style radio commercials; it inhabits a middle territory

between Roy Wood’s Mustard and Sigue

Sigue Sputnik’s Flaunt It!! It was

lucky to make #43.

Feargal Sharkey

I never bought the patronising notion of the Undertones

being happy, innocent boys from Derry/Londonderry; no one could have grown up

innocent in that era. And their more straightforward, boisterous boy-punk-pop

(or was it that straightforward? "Teenage Kicks" is an ode to

self-pleasure, as, more subtly, is "My Perfect Cousin," and the

latter was hip enough to namecheck the Human League a year before they started

having hits. Moreover, the hero of "Jimmy Jimmy," if hero he be, ends

up disappearing one night - and anyone involved in the Troubles at first hand

would feel the instant, deep chill engendered by that line) became increasingly

balanced by a gradual enlarging of their canvas - the Afro off-beats of the

nuclear war-heralding "It's Going To Happen!," the ravaged

psych-semi-lite of "Beautiful Friend" and "Love Parade,"

the unsettling question mark balladry of "Wednesday Week," perhaps

above all the exquisitely tortured liquidity of the 45 version of "Julie

Ocean," which latter really penetrated me in my first term at university,

reading Joyce's Dubliners (especially

"The Dead").

The conflict which made the Undertones worthwhile - in

their semi-unassuming way, they are one of the great singles bands - lay

initially between the new wave thrash of the music and Feargal Sharkey's

uncannily pure and technically agile voice, like a contralto Count John McCormack. The white soul forays of their

final days ("Got To Have You Back") suggested that this was the way

Sharkey was destined to follow; his first record after the Undertones split,

"Never Never," recorded with Vince Clarke under the banner of The

Assembly, was a sufficiently big and convincing hit (#4, November 1983) to make

him feel that he was doing the right thing.

Whereas in 1985 the rest of the Undertones regrouped

under the notably more aggressive That Petrol Emotion (though 1987's "Big

Decision," Madchester three years ahead of schedule, was unlucky not to go

Top 40), Sharkey went for the mainstream. John Peel commented at the time that

he was absolutely happy with Sharkey's new solo success, even though he was

moving into a mainstream which to Peel was lifelong anathema; unlike other

previous Peel discoveries such as Marc Bolan, Sharkey remained close friends and

didn't turn his back on him the second he had a number one.

Maria McKee, meanwhile, came close to a hit in 1985 with

Lone Justice's "Ways To Be Wicked" - a coruscating vocal performance,

and infinitely more arresting than that which eventually did bring her a number

one as an artist. But as a writer she was responsible for "A Good

Heart." The song is good - a more upbeat variant on the lyrical theme of

its predecessor at number one, but also a more realistic and cynical viewpoint

("I know that love is quite a vice") - and Sharkey's performance

uncannily powerful, ranging from his spiteful "experts say" to his

soaring "please be gentle with this heart of mine."

But alas we have to listen to it through the Pernod gauze

of the sickly production by David A Stewart; thus the gloopily booming

syndrums, the "soulful" backing vocals, the spittle ponds of

Fairlight mucking about which render both McKee's song and Sharkey's singing

utterly sterile - and, as is so frequently the case, a record which sounded

expensive in 1985 can end up sounding horrendously cheap a generation down the

line. The career didn't last, and Sharkey eventually gave up singing and went

behind the A&R/management scenes, but I still think somebody (McKee? Rick

Rubin?) should coax him back into the studio and record this song in a way that

allows both it and him to breathe.

You Mustn’t Be An

Angel

And to think you

could have had the Associates...

The eventual long-term global success and enduring appeal

of the Eurythmics are depressing reminders of how little the music-liking (as

opposed to loving) public is prepared to settle for. The title of their fourth

album, Be Yourself Tonight, fittingly

saw them disrobe themselves of their possibly bogus New Pop coats, revealing themselves

as the hoary old pub rockers they perhaps always secretly wanted to be, clogged

up as the album is with ROCK and SOUL and LULU'S BACKING SINGERS. Never mind

the Bunuel Technicolor dreams, the su(per)reality of the Associates, or the

early Simple Minds - "we" were satisfied with hollering voices, solid

fretwork and that hugely irksome "I'm mad me" persona which Lennox in

1985 wore very poorly indeed.

And to think you

could have had Scritti Politti...

The Eurythmics of 1985 served as a direct inject anti-New

Pop Hoover, meticulously and mechanically sucking in everything that was ever

notable or mischievous or genuinely sexy about pop in order to spew out a

bland, tasteless, compressed, compromised cocktail of crap. Be it Aretha or

Costello, they were reduced to mere dots on Stewart and Lennox's VDU screen,

humbled signifiers of what 1985 was happy to call "soul."

And to think you

could have had the Cocteau Twins...

What angers me most about "There Must Be An

Angel" - not least the fact that it got to number one whereas the

Cocteaus' infinitely superior "Aikea-Guinea" stopped at #41 (1985 was

a year when the majors harshly regained control and the indie market was

effectively locked out of the Top 40, such that even the Smiths and New Order

no longer had a guaranteed passage into the lists. Meanwhile, the Mary Chain

were on WEA - and "Never Understand" and "You Trip Me Up"

were as important to us as any of the above at the time - but they couldn't get

past the low forties or high fifties and would only penetrate the Top 40 at the

exact point where they ceased to be interesting ["Some Candy Talking"

one summer later]) - is that Lennox's dainty wordless scat singing seems to be

a direct attempt to copy Elizabeth Frazer, or worse, neutralise her for the

mass market. Her lead vocal is one of the most annoying of any such vocal

performances on number one singles; the rhyming of "theeeeees" with

"bleeeeeeeeees" over far too many syllables - and incidentally, how

exactly does one get "thrown and overgrown by bleeeeeeeeees"? - her

inability to shut up and breathe, the horrible echt-gospel "watching

angels celebrating" sequence, her "yey-ey-hey-ay-ah"s, all

redolent of pop's own Widow Mangada. Even yet another ‘phoned-in Stevie Wonder

harmonica solo - the fourth number one involving Wonder in less than a year,

all of a sudden - cannot save its false euphoria, its worship of sub-soul

stodge.

And to think you could have had the future. Shame on

"you" all.

1985 Wine Bar Male

Divorcee Checklist

“Real,” “raunchy” rock, like they did it in 1974, but

scrubbed enough to pass as up-to-date.

Songs about empty rooms or separate lives or it only

being love for you to snivel over like a blocked Porsche carburettor.

Sigh of relief that this country still isn’t as bad as

Communism. If only poor, imprisoned Nikita could see sense and taste the “freedom”

of unbridled capitalism.

After all, you have your own van, don’t you?

Reggae-lite. The contentment-inducing familiarity of

twenty-year-old songs when you didn’t have to worry about anything. The

contemporary treadmill. “You’ll wish that you had not…” And your teeth grit

until they begin to bleed.

“Body rock!” Pop traduced to the level of deodorant

commercials.

“I need your BODY! And SOUL!” Who is this Coleman Hawkins geezer

anyway, Rip van Winkle? You can’t go wrong with Animal Nightlife.

Mad Max 3. The

first two were all right but look how much better and more accessible it is

with big budgets and famous people as villains! Tina Turner is one of the great

powerhouse performers, and no mistake! It’s like “What’s Love Got To Do With

It?” but with comic books. Tell you what, you can never go wrong with Mel Gibson.

Number of times

you went to see Mad Max 3: Four.

Number of times

you went to see Mrs Soffel: None.

I hate what I’ve allowed myself to become. But I’ll die

before I admit it to you, plonker.

Adorno on Pop, Part One (of three): The Technological Veil Stripped By Its Syncopated Technique

The reason it works so well in a 1985 context is that Ure retains the sonic fullness which he learned from Conny Plank at the Vienna mixing desk, so "If I Was" provides a refreshingly full reminder of the sublime richness of New Pop production at its (1981-2) peak amidst the blustering bigness of its 1985 peers. There have been several occasions on Then Play Long when I've been taken aback by liking a record about which I felt I would be at best politely indifferent, and in this case I'm pleasingly surprised at how well "If I Was" has endured.

Money For Nothing (Part 1 of 2)

Good to see Siouxsie making it through to Then Play Long at last, with a song Brett Anderson still counts as one of his favourites; the 12-inch is the full Goth dancepop deal, but pop Ozymandias manifests as the singer observes the ruins of Pompeii and wonders: where did all those riches get you? We'll be getting back to that question.

Adorno on Pop, Part Two (of three): The De-Individualisation Of Suffering

Adorno on Pop, Part One (of three): The Technological Veil Stripped By Its Syncopated Technique

“…what enthusiastically stunted

innocence sees as the jungle is actually factory-made through and through, even

when, on special occasions, spontaneity is publicised as a featured attraction.”

(Adorno, On Jazz, trans. Samuel and Shierry Weber.

Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 1981 edition; p 126)

“Please don't reject me/In anger or in sorrow/You've got to accept me/If we're to make a better tomorrow”

“Please don't reject me/In anger or in sorrow/You've got to accept me/If we're to make a better tomorrow”

(Level 42, “It’s Not The Same For Us”)

It was Mark Sinker who, in

response to a question posed to him on a message board in February 2002 (as it

turns out, by myself), said of Level 42 that World Machine represented a “top Adornoite dissection of “modern”

(e.g. 1986) life." Over the ensuing twelve-and-a-half years I have intermittently returned to the record and wondered whether "Adornoite pop" wasn't an irresolvable contradiction in terms.

I do not imagine that Adorno would have had any time for pop

music whatsoever, and even less so for what could inadequately be described in

the eighties as “jazz-funk,” which to him, I am sure, would have represented his

aesthetic bugbear of perennial sameness, with any notions of “contrariness” and

“conflict” ironed out after decades of trammelled compromise.

Not being an Adornoite epigone, however, I have to remind

myself that when Adorno talked about “jazz” he was speaking of, essentially,

Weimar cabaret music rather than the contrary conflicts proposed by Armstrong,

Ellington and Morton. Therefore I’m not at all certain that he would even have

tried to detect the arteries of conflict which run through World Machine; the record’s cover, for instance, which isn’t that

far away from OMD’s Organisation, depicts

the Hafnarfjall mountain in west Iceland on the point of being superseded by a

large, unlovely, pink junction of nuts and bolts. Moments of awe cancelled out

by the reminder that something is always being advertised and proposed (in that

order).

But although the focus of World Machine varies between overall worldview and zoning in on the

slow, methodical wreckage of people’s own lives and relationships, it would not

really be correct to describe the record’s aesthetic as Brechtian, since that

depends on a certain degree of detachment on the part of the audience, rather

than the workings of the art itself. Even if many Porsche drivers bought this

record and took it to number three on the basis of pounding – or perhaps “pouring”

is a better noun here - it out of their wall-to-wall car speakers, anyone with

half an ear open would realise before long that the record’s apparent smoothness was the reddest of

herrings.

The opening title song sets out the record’s worries, rather

than any principles; it essentially confesses that the “1985”-ness into which

society has pushed itself (after being persuaded to do the pushing) is worth

nothing. Mark has in the past commented on Mark King’s “lost robot voice” – I’m

not sure whether that’s exactly what he said, but it’s what I remember him saying – and, coupled with

Mike Lindup’s remonstrating angel vocal counterpoints, I think that this is

both right and proper for the music. It is like Mose Allison filtered via a

crash-landed HAL. There is no need for King to “emote” as such – as a bass

player first and singer very much fifth, his voice would in previous eras have

passed the “Your Father’s Moustache” big band test – and his immaculate,

wrecked, besotted performance throughout World

Machine demonstrates that a “blank” and “expressionless” voice is able,

especially in 1985 terms, to convey more “soul,” “passion” and “honesty” than a

mountain of sweaty melisma.

Three other helpful examples

of “blank” expressionism in 1985 pop:

Bernard Sumner – “Love Vigilantes”

Robert Wyatt – “Alliance”

Curt Kirkwood – “Two Rivers”

But education, “Uncle Sham” and “the party” do not impress

King, still less the basic urge to propagate human life (“Some folks try to

multiply/From sunrise to sunset/Leave behind more of their kind/So no one will

forget”). He is able to make you believe the deeper implications of the

expression “the party’s over,” and if we seem to travel into Gary Numan

territory at times – “And I don’t know if I belong – TODAY/I don’t know why my

friends have gone – AWAY” – the poignancy is harder won. This is somebody whom

the world machine may elect to leave behind, old, spare stock that is no longer

needed or even desire. And he does not like the prospect.

“A Physical Presence” offers no respite, despite showing

that the group could do The Police better than The Police; King cannot do what

he is expected, they both know it and patience has been lost (“Don’t you

remember all the nights you shared in my disgrace?”); his two exasperated “Ow-ow-OW!”s

describe and communicate more than half-a-dozen albums’ worth of Phil Collins’

bar-room weeping-as-self-pleasure methodology. They could, in themselves,

encapsulate the 1985 dilemma.

In this context, “Something About You” – in case you were

wondering – takes on an additional emotional heft; King is aware that whatever

they had is over, and also of the hollow façade of the pretend way of living

that brought them “here” (“Drawn into the stream/Of undefined illusion/Those

diamond dreams/They can’t disguise the truth”) – but still he believes in

elements of those dreams, enough of them to keep him trying, and so the song

takes on a slow-motion sunset worthy of Japan’s “Taking Islands In Africa” (don’t

let the double-speed rhythm deceive you; they’re only human, after all). Adorno

again: “With jazz, a disenfranchised subjectivity plunges from the commodity world

to the commodity world; the system does not allow for a way out.”

But Level 42 are already digging their tunnel.

“Leaving Me Now” replays the break-up sunset of “Something About

You” in slower motion, closer to the ear and heart. He knows she has cheated

and that there is no way back; he still loves her almost beyond reason (“Some

people kill for less/But I’d still die for you gladly”) but there is something

about the song’s constructions, its elliptical gaps, the music chasing the

contemplation of the words, that reminds me of The Smiths (the song partly

anticipates “I Know It’s Over”) covering “At Last I Am Free,” complete with

Wally Badarou’s arpeggiated piano figures being left alone in the dancehall at

the end.

There is something terrible – in the sense of “terrifying” –

about the line “Not even love could bring you to stay/This time.” This is what

an unregulated free market has done, is doing, to people’s lives; the illusion

superseding the less colourful but infinitely more worthwhile reality. And yet,

if we consider how infrequently the adjective “mesmerised” appears in pop

music, we must note how everything in this song works up to, peaks at and

climbs down from that “mesmerised”; it is the lament’s cynosure. Once individuality

becomes an exchangeable currency, Adorno warned, individual suffering counts

for virtually nothing, and here are the ashes.

“I Sleep On My Heart” edges the conflict further; he is now

alone, in bed, eyes shut but still dreaming of her. What does he see when he

opens his eyes? “I’m sitting here surrounded by possessions/Objects that

confront me night and day/The fruits of my material obsession/But it seems the

more I earn, the more I have to pay.” And thoughts go to another group whose

1985 album was recorded very, very far from home (whereas Level 42 may be very,

very far from anywhere in the Isle of Wight; that can have its advantages as

well as its disadvantages) yet who, like Level 42, never sounded more like

themselves – R.E.M., and Fables Of The

Reconstruction, done with Joe Boyd, full of songs which only make sense to

themselves, with snapshots, recollections from a shared past to help overcome

rainy desert island isolation (“Feeling Gravitys Pull,” “Wendell Gee” and the

breathed explosion that is “Can’t Get There From Here”).

“It’s Not The Same For Us” could be a description of

somebody trying to reach a faded poster of Big Brother, with warnings of how

future generations shouldn’t repeat the mistakes of previous ones. “Our leaders

live in the past,” sings King, “We can change it!/There’s something to hope for

AT LAST!” Who are the song’s “us”? The group? Their hoped-for constituency?

Ourselves? I like to think that they are still interchangeable.

“Good Man In A Storm” could be interpreted as Gaye’s “Piece

Of Clay” for the Partridge generation; he has tried all his life to be the

mythical Perfect Human, but is always failing and fears what might happen as a

result of his failures, with the implication that he is in charge of something

(“When those around me fall in despair/I call upon my common sense ‘cos someone has to care”); “World Leader

Pretend,” anyone?

“Jazz is the false liquidation of art – instead of utopia

becoming a reality it disappears from the picture.”

(Adorno again)

(Adorno again)

“It just occurred to me/I must be blind”

(Level 42, “Good Man In A Storm”)

(Level 42, “Good Man In A Storm”)

But then pop tries to justify or accommodate Adorno; “Coup d’Etat”

spells out what the rest of the record has been merely implying – that pop, in

the wider frame of society, isn’t enough.

There’s a revolution, there’s blood and there’s death – and it is all as

meaningless as the smile previous wiped from the singer’s face. The record ends

at the terminus of “Lying Still” – a title that could be interpreted in at

least three different ways – in which the couple physically reunite even though

their hearts are no longer in it; it is like the husks of Winston and Julia

that are left at the end of Orwell’s book except there is this REFERRED PAIN

which IRRUPTS the chilled, or chilling, placidity – SHE is not feeling what she

said she felt, and HE feels that too; yet still it’s too late, the world

needlessly atomises again, but it’s all right as long as the music still

drifts. Except that, right at the end, it drifts into Schoenbergian atonality.

What was that about a dialectic of loneliness? Who’s the patient, and where’s

the couch?

Statements For,

Leading To Against, Reversal Into Unfreedom

Introduced by the recently departed Mike “Snowy” Smith, “Election

Day” was one of the most depressingly pretentious Top Of The Pops performances I have ever seen. There’s Simon le

Bon, pompously walking down some stairs in a hideous cravat, collar and

overcoat like he owned the place, briefly breaking into some sub-Bryan Ferry “dancing,”

before deigning to sing this piece of apoplectic nonsense. The song – which

actually speaks of “re-election day”;

what is this, roll on 1987 and Maggie? – scarcely exists. Grace Jones ‘phones

in a cameo appearance which threatens to bring the rest of the record crashing

down around it (“We could DIEEEEE, oh…”) and reminds me of the song which

SHOULD have been here in its place, viz.:

Slave To The Rhythm

as in the album Slave To The Rhythm by Grace Jones as in the biography

masquerading as a single masquerading as the album Slave To The Rhythm by Grace

Jones as in the assassination plot masquerading as the kiss Slave To The Rhythm

by Grace Jones does not appear to have been remastered on SACD and may not even

be available at the moment and yet at 40 minutes it is the greatest single ever

made as of any day and should have been marketed as and allowed to be a single

as as a single it is singular.

Slave To The Rhythm

as in The Annihilation Of Rhythm is an unsurpassable dissertation on the centre

of the universe with such a universe being defined at its borders as Ian

Recites Ian and how close to PJ Proby does Ian McShane sound on his

contemporaneous cover of Drive by the Cars on his seldom-bought 1985 album Ian McShane Sings and is that why Morley

hired him to read Penman on the album Slave To The Rhythm by Grace Bones?

Slave To The Rhythm

as in the Annihilation Of The Universe Following The Collapse Of Its Centre

Namely Miss Grace Jones and if we lost Grace Jones would we truly find Grace

Jones is a disquisition on celebrity and the dissolute calumny of pop music in

1985 without much in the way of jouissance

or plaisir but she talks with Paul

and Paul and laughs a lot and gives away precisely nothing including the

possibility that she might not be the centre of the universe.

“And you?”

QED.

Slave To The Rhythm

as in the Seduction Of Grace Jones Necessary For Entrapment is at times

forceful and militant at other times haunting in its delicacy (“The Frog And

The Princess”) at yet other times fucking about with Berio (“Operattack”) and

for one more time the song itself.

Slave To The Rhythm

as in The Song Itself ends with the previously noted indrawn breath of God but

also the sharp intake of gulp from Miss Jones exactly as if she had just been

shot.

Slave To The Rhythm

as in the Prejudged Autopsy of Brace Jones contains words from her sometime

lover Jean-Paul Goude who amongst other things muses that the best option would

be to kill Miss Jones and then make the record about her in an Inspector Morse sense. However, I don’t

subscribe to this point of view, in a sense which certainly isn’t confined to

1985, since

Slave To The Rhythm

as in a record unimaginable without the prospect of Melody Nelson, survived,

ready to remake Sunderland in her own graceful image.

I don’t know quite when, how or why the Duran bubble began

to burst in Britain. Splitting into two not very satisfactory subsections?

There is the belief that their playing Philadelphia, and not Wembley, was what

began to do for them here. They should have been here, so some said. But they

made the mistake of believing their own, non-self-generated publicity, and

letting a residual 1972 “attitude” get in the way of their often quite sombre messages.

Out of a mixture of those reasons, and others not specified, they came back

with a new Duran Duran album the following year, but was there anybody left to

listen?

Blue

Is the opposing bookend to “Election Day” but I’m not sure

it’s any more helpful. Roland Gift is angry about what The Government are doing

to him and his, and not without reason, but he sounds petulant rather than

enraged and so the single stopped at #41.

Forever And Ever

Ure's only solo number one was largely achieved as a result

of immense post-Live Aid goodwill, and although the song is superficially

another list song ("If I was a painter," "If I was a poet,"

etc.) it isn't hard to deduct a few good-natured sideways jibes at Geldof in

such lines as "If I was a stronger man/Carrying the weight of popular

demand" or especially "If I was a kinder man/Dishing up love for a

hungry world." Ure was and remains respected as the quiet backroom boy who

got on with facilitating the actual Band/Live Aid work while Geldof roared and

bellowed in the foreground, and both his humility and good humour come through

strongly here. Though worlds away from the diseased howls of side two of Ultravox's

Rage In Eden (from which Ure's Ultravox subsequently and noticeably

backed away), "If I Was," though a minor work, is thoughtfully and

intelligently assembled and executed. Bassist Mark King, on loan from Level 42,

wisely kept his lines simple, even though they appear to owe something to the

bassline of the Jacksons' "Can You Feel It?" and Ure as arranger and

producer is sufficiently astute to vary his backing from verse to verse and

chorus to chorus, from the bountiful bounce of the chorus itself to the vague, humming

threat of the "Come here my baby" sequence.

The reason it works so well in a 1985 context is that Ure retains the sonic fullness which he learned from Conny Plank at the Vienna mixing desk, so "If I Was" provides a refreshingly full reminder of the sublime richness of New Pop production at its (1981-2) peak amidst the blustering bigness of its 1985 peers. There have been several occasions on Then Play Long when I've been taken aback by liking a record about which I felt I would be at best politely indifferent, and in this case I'm pleasingly surprised at how well "If I Was" has endured.

Money For Nothing (Part 1 of 2)

Good to see Siouxsie making it through to Then Play Long at last, with a song Brett Anderson still counts as one of his favourites; the 12-inch is the full Goth dancepop deal, but pop Ozymandias manifests as the singer observes the ruins of Pompeii and wonders: where did all those riches get you? We'll be getting back to that question.

Adorno on Pop, Part Two (of three): The De-Individualisation Of Suffering

In the 30 November 1985 edition of the NME was a Top 100 (or Top 99; readers were invited to pick the

hundredth) Albums list compiled by its then staff. It was a notably pious and

somewhat joyless affair, the records served up as a kind of righteous school

dinner which readers must ingest to teach them respect, or socialism, or

something like that. And, as several commentators at the time gleefully noted,

it was also a rather presumptuous listing. Was Mad Not Mad really the fifty-fifth greatest album ever made? Better

than Music From Big Pink or A Love Supreme?

The NME’s Danny

Kelly compounded the problem by admitting that Psychocandy probably would have made it into the list, had it been

released two weeks earlier. Simon Reynolds and David Stubbs were about to start

contributing to Melody Maker.

Moreover, when the end-of-year NME critics’

album poll came out, Mad Not Mad was

only in fifth place (Psychocandy came

joint top with Tom Waits’ Rain Dogs).

What was anybody thinking? Moreover, was anybody thinking? Such questions are

always happily asked with the privilege of hindsight.

In the intervening twenty-nine years, few people have had

anything kind to say about the record, including Madness themselves; Suggs

famously referred to it as a “polished turd” and the musicians admitted that

they felt weary and running out of enthusiasm while recording it. Nor did it do

very well commercially; it peaked at #16, and the group, already without Mike

Barson, disbanded the following year. In addition, it appears to have drifted

out of print; apart from its inclusion on the album box set The Lot, it has disappeared from the

shops. Where deluxe editions of One Step

Beyond, Absolutely, etc. are easy

to find, it would seem that Mad Not Mad

has been quietly written out of the group’s history (look at the prices for the

deluxe CD edition online and weep).

Listening to the record again, after a quarter of a century

of not doing so, I feel the question that really needs to be asked is: was Mad Not Mad really the fifty-fifth best

album ever made? My suspicion is that it might still be. For this is an already

decimated band of musicians at the end of its tether, audibly falling apart

and, in large part, saying the unsayable. Mad

Not Mad is the group’s The Visitors;

an unnerving distortion of everything you ever knew and felt about Madness, and

its darkness is equal in kind, if not in nature, to that of World Machine.

This is even less surprising when you put the record on and

it immediately sounds like…Level 42, with funky (possibly sequenced) clavinet

and stuttering brass lines. The music then flails back into what it expects us

to recognise as Madness, but the musicians’ hearts are not in it; Suggs sings,

deeper in tone than before, of being willing to do whatever crap the music

industry throws at him, even though he believes not an atom of it. The song is

called “I’ll Compete” (“For all that it’s worth…”) and you can sense the joy

and humour being squeezed out of their music like the juice from an errant

prune.

The notion of getting older – bear in mind that these

musicians were, in 1985, largely in their early or mid-twenties – is carried

over into “Yesterday’s Men,” that most reluctant of Top 20 hits. Lee Thompson’s

saxophone projects Sade-ness, while Suggs sings quietly – and not unlike Robert

Wyatt – about being somebody for whom there is no room in the fantastic new

market-driven world, people who have been left behind (the heartbreaking

transition between the hopeful “It must get better in the long run” and the quietly

terrified question “Will we be here in the long run?”). David Bedford’s strings

quote “Spanish Harlem” and Afrodiziak and (the future) Londonbeat are (mostly)

present, providing solemn backing vocals. Indeed producers Langer and

Winstanley throw everything at the wall of presumed silence here; the record

plays as though Madness are struggling to assert themselves, or even survive,

amidst the whirlpool of Steve Nieves, Judd Landors, Luis Jardims and what have

you (Nieve actually does a very good job of standing in for Barson on

keyboards; on the first three songs in particular, you could be forgiven for thinking

that he was Jerry Dammers).

But “Uncle Sam” underlines the problem; the group do their

best to come up with an old-style Madness skank-along singalong, but they sound

bitter and forced (remember, they are talking about Reagan’s notion of America,

rather than the United States as such) and Daniel Woodgate’s drums sound

particularly furious in their hammering. Even a TOTP performance couldn’t prevent “Uncle Sam” from becoming the

first of their twenty-one singles (at that point) not to make the Top 20 – it peaked,

perhaps symbolically, at #21.

“White Heat” plays like a summer in hell; the curlicues of

its melody and chord changes suggest Saint Etienne’s gruff uncle, with all the

talk of “the pavement is melting/Crumbling for the luckiest girl”; meanwhile, in

the 1985 equivalent of Turnpike House, the protagonist is squatting on the roof

to avoid the loan sharks skulking around his front door, while kids throw

missiles of unspecified origin at passers-by. “The whole world is melting,”

sings Suggs, and you believe him. The title song seems to be the obverse of “Primrose

Hill” – the windows being thrown wide open, Georgie Fame and the Blue Flames

audible on the stereo – while Suggs asks his unspecified Other whether she

would “dance with a madman/Over the hills and far away” (“contrasted as a Self against

the abstract superimposed authority and yet can be exchanged arbitrarily”).

The sticking point for a lot of people was their version of “The

‘Sweetest Girl’,” but I am prepared to look at this in a kindly manner, not

least because an actual ex-Scritti person (Tom Morley) was present. If

anything, the group has fun playing with the song’s elements; it doesn’t

compare with the Scritti original, but it is interesting that Suggs is singing

the song exactly as Robert Wyatt might have sung it, with the same jolly

dissonances and interruptions that we know from Nothing Can Stop Us. Of course they get the words in the wrong

order and mess up the song’s eventual meaning, but they are enjoying

themselves, perhaps for the only time on this record.

From hereonin, it’s emotionally and sociologically downhill all

the way; “Burning The Boats” – the group’s “Style Council song” – wins this

week’s Could Have Been Written Last Week award, with its subject matter of

London systematically being shut down and sold off to the highest bidder. More

than once, an exasperated Suggs protests: “Come on, tell me – who’s this for?” Meanwhile, his

telephone is being tapped (on which Afrodiziak sardonically comment).

“Tears You Can’t Hide” is funereal lovers’ rock as Suggs

looks to the person, or people, to whom all this is being done and urges them

to stay together. “Time” revives the ungainly “Shut Up” gait – with an

instrumental break which, again, anticipates The Smiths (specifically “Sheila

Take A Bow”) – while Suggs grimly meditates on the declining state of the world

(“The sky looks very Blue today,” “It’s so sad but we don’t seem to be going

forward at all”). “Come on, Time,” he cheerfully says, as if Time were his dog –

but the final “Time, gentlemen please” feels like the most final of last

orders.

“Coldest Day” ends the record; he is listening to the radio,

hearing about Marvin Gaye, and then the camera pans out to Johannesburg, and a

hopeless world for which (again) pop music seems to have done nothing. A muted

ending to a deeply unhappy record – and once again, those unnerving dissonances

right at the end, “being accepted into a community of unfree equals.”

Adorno on Pop, Part Three (of three): New Pop's Struggle to Survive in an Unforgiving World of Capitalist Modernity

The second Lloyd Cole and the Commotions album did not

exactly find favour with the musicians involved, either. Lawrence Donegan went

so far as to call it “terrible.” Cole himself felt that the group had been

pressured into making a second album too soon and eventually disowned some of

the record’s songs, while the critical response was muted, critics no doubt

having expected a second helping of arty student flat capers.

Commercially, however, Easy

Pieces spawned three Top 40 singles, two of which made the top 20, and as

an album it sold more copies in its first fortnight than Rattlesnakes had in a whole year. I am not sure what anybody who

bought it was expecting.

Certainly Polydor wanted a “commercial” record, and when

initial sessions with Rattlesnakes’

producer Paul Hardiman yielded nothing of note, they sent for Langer and

Winstanley, who drafted in the Londonbeat boys again, as well as perennials as

Gary Barnacle (who actually appears on all three of the albums I have discussed

at length here). Complaints were made about sonic blandouts, In the NME, Danny Kelly – again – described the

album as “that most simultaneously fine and useless of creations, a very good

pop record,” a remark which probably enhances the explanation of why the mid-eighties

NME was up creek sans paddle.

But, if actually

listened to, Easy Pieces is

anything but – it is a far darker set of songs than were to be found on its

predecessor, and the relative sonic opulence of the record helps accentuate the

darkness. More so than World Machine,

this is a record about two people – possibly the same two people throughout –

falling apart in a world that (though only hinted at twice) really has no place

for them. Any record which begins “She left you 1958” is not going to be a

laugh a minute, or indeed any minute. “Rich” dwells on the fate of the big star

who has nobody and nothing to fall back on except drugs and random sex, and for

whom the subsequent history of pop, as emphasised by Cole’s string of

quotations at song’s end, has demonstrably done nothing, and may even have made

him worse.

“Why I Love Country Music” is a bitter break-up song, all

about smiling and living the lie until you crack – and, once more, music cannot

provide a remedy. “Pretty Gone” finds her, so to speak, gone. “Grace” is about

a state of mind – the 28-year-old junkie Cole is addressing appears to be

called “Jesse” – and Cole seizes the word “gutter” and spits it out of his own

mouth. “Cut Me Down” may be a complaint against Cole’s record company, or (like

Level 42) a pained meditation on how impossible love in the time of Thatcher

seemed to be.

“Brand New Friend” and “Lost Weekend” are sequels to “Why I

Love Country Music” – the “Jane” in both songs appears to be the same Jane –

and “Rich” respectively, whereby the superstar goes through casual hell in

Amsterdam. “James,” the record’s darkest and quietest song, sees Cole

out-Morrisseying Morrissey as he sings, haltingly, about somebody who can’t

come out of the shadows, who may or (probably) may not have done something

terrible, who will forever wake up on the same day with the same hopeless

dreams because…what was that thing about capitalism only rewarding the people

it wants to, and virtually nobody else besides?

Cole dismisses “Minor Character” as bad Raymond Carver, but

I think that’s unfair; possibly a parallel song to “Grace,” this finds a

suicidal woman, laughed at by her Other, considering suicide and never quite

getting there, unless, at the end, she does. To finish us all off, there is “Perfect

Blue” – possibly the same “Blue” against which Roland Gift railed – in which Cole

may well be singing to his listeners, signing off with a warning: “I may be

blue…but don’t you let me make you blue.” A patient instrumental coda – and then

that black dog of quiet dissonance again, everything dissolving into huge,

threatening clouds of rust and spit.

Happy Ending?

A gay love song which never has to spell it out, and so few

pop songs have the guile or courage to include lines like “When you hold my

hand, I want to cry.” “You Are My World” is really all build-up and take-down,

structurally, but the post-Bronski Somerville feels liberated. The Communards

named themselves after the inhabitants of the Paris Commune, which ended

bloodily in 1871 after a very short period (two months and ten days). One side

said: new way for human beings to live and function together. The other side

said: insurrection. The dilemma is still being worked out in contemporary

politics, and not always tidily.

But Wait A Minute, or, Money For Nothing (Part 2 of 2)

The follow-up to “19” that you never hear, and an

immeasurably better record, not least because Hardcastle sounds more involved

and committed – indeed he is audible on this record, as the hapless Great Train

patsy. Laurence Olivier – who at this point was appearing in hologram form at

the Dominion Theatre in Dave Clark’s musical Time – makes a unique appearance on a pop record as a sonorous

funereal narrator, while Bob Hoskins has evident fun as both Great Train Robber

and Al Capone (and, in the video, as a cackling, cigar-wielding Number 2 of a

King). All allegorical, of course, about the lengths some people – or, in 1985,

should that have been most people? – will go to in order to lay their hands on

money. More disturbing than “19,” too; Olivier’s final summing up and

sentencing should have been enough to chill any trainee broker. The appearance

of the Miami Vice theme directly

afterwards – as if to indicate that a lot of people in 1985 still found this

sort of thing attractive and glamorous – is a political gesture in itself.

Tarzan

Essentially a collaboration between Irish ex-Red Cross

worker and ex-Dee D Jackson dancer Jimmy McShane and Italian musician and

producer Maurizio Bassi (who may even have sung lead vocal on their biggest

hit), “Tarzan Boy” was 1985’s big Eurodance hit, but despite their continuing

popularity in Europe, they were unable to repeat the record’s success in

Britain. McShane contracted Aids and died in March 1995, aged thirty-seven. “Tarzan

Boy” is remembered with great affection by those old enough to remember it, and

so in certain circumstances it still proves to be a nostalgic floor-filler. To

those under the age of thirty, however, the record may be of little or no

significance, and would more than likely clear a modern dancefloor.

The dancefloor really is the great adjudicator and leveller

of pop culture. Essentially dancers want the sound of now, or the last two

years at the most. The reason why really obvious older records such as “Y.M.C.A.,”

“I Will Survive” or anything by Abba, Blondie, the Chic Organisation, Donna Summer, Saturday Night Fever-era Bee Gees or

early (1983-7) Madonna continue to get played is because, predictable or not,

they still work on the dancefloor; they are of their time, yet in terms of

production, arrangement, approach, presentation and performance have become

timeless.

The same is true of pop songs today. A salutary rejoinder to those who bemoan the absence of "proper songs" in contemporary pop can be found on Mandatory Fun, the excellent new, US album chart-topping record by Weird Al Yankovic; in the medley "Now That's What I Call Polka!," which finds Yankovic tackling the likes of "Timber," "Wrecking Ball" and "Scream & Shout" in the polka style, skewering with quiet smartness the notion that the great pop song is a thing of the past; if these songs can fit into a polka framework, then there is basically nothing wrong with them, except perhaps for the way in which the original versions are performed, produced and marketed.

The same is true of pop songs today. A salutary rejoinder to those who bemoan the absence of "proper songs" in contemporary pop can be found on Mandatory Fun, the excellent new, US album chart-topping record by Weird Al Yankovic; in the medley "Now That's What I Call Polka!," which finds Yankovic tackling the likes of "Timber," "Wrecking Ball" and "Scream & Shout" in the polka style, skewering with quiet smartness the notion that the great pop song is a thing of the past; if these songs can fit into a polka framework, then there is basically nothing wrong with them, except perhaps for the way in which the original versions are performed, produced and marketed.

Some sobering thoughts, there.

Cameo

Hold on, is that the future coming through? Who said New Pop

was finished? I have to admit that “I’d like to tie you up awhile” comes

awfully close to being a 1985 “Blurred Lines” but in terms of production,

arrangement, approach, presentation and performance this is like Ronald Shannon

Jackson and the Decoding Society disrupting a Sigmund Romberg conference.

Todd

For once, Derek Bramble’s production works with, rather than

against, the music; and what music – taken from Utopia’s P.O.V. album, this is one of Todd Rundgren’s great white soul songs

(which Graham and Grant take back to its source), and it seems to provide a

shelter for all the people who have been systematically excluded from the world

and 1985 throughout the rest of this record. “They’re afraid you’ve been

blinded/But I already know how it’s going to be”; “Nobody else understands what

I’m doing/Nobody else makes me act this way”; “And you know we’ll still be here

tomorrow” – and, hold on, is that a sunrise?

“I see things far ahead, maybe light

Maybe beautiful children

I don’t have words I’m thinking of

But it’s way beyond what

they call love.”

“It is the true message in a bottle”

(Adorno, and not the way he meant it)

August, everywhere.