Thursday, 21 October 2010

LINDISFARNE: Fog On The Tyne

(#108: 25 March 1972, 4 weeks)

Track listing: Meet Me On The Corner/Alright On The Night/Uncle Sam/Together Forever/January Song/Peter Brophy Don’t Care/City Song/Passing Ghosts/Train In G Major/Fog On The Tyne

Many of you will recall the seventies British situation comedy Whatever Happened To The Likely Lads. In their original sixties incarnations Rodney Bewes’ Bob Ferris and James Bolam’s Terry Collier were appropriately laddish swingers of the Men Behaving Badly variety, but when they returned in a different decade they found that their world had changed. Bob had moved steadily upward into the white-collared middle classes of Newcastle, but Terry had been away in the Army and comprehended almost nothing about the city and the people to which he had returned. Things hadn’t really worked out for Terry, but he seemed infinitely more assured (and resigned) about his current station in life than his ostensibly better-off mate.

Much of the comedic content of the series has not endured; it is largely typical fear-of-mother slapstick which has dated badly. But the elements which have remained with me are the lengthy, non-comedic interludes where Bob and Terry walk around their city, watching the haunts of their younger days, the buildings and things they assumed would always be there, being demolished and destroyed, with nothing much (as yet) to rise in their place. The feeling would be familiar to almost any British city dweller of the period but the remembrances are auburn and rueful; where are our roots now, where exactly do we go from here? The British economy was in almost as bad a state as now, and familiar mutterings about cuts to public services were in effect. Is anything, you wonder while watching these virtual documentaries, going to survive?

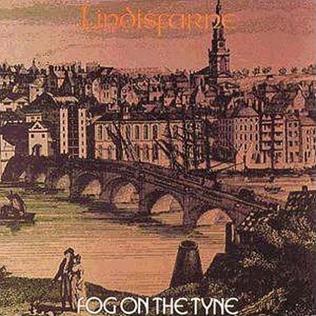

I say this because it may go some way towards understanding why Lindisfarne – on the face of it, an unpretentious, good-time folk-rock group from Newcastle – became so popular during this period. Folk music is about the most difficult of musics to categorise, since there is a different strain of folk which applies to every different village, and in some cases every different street. But something about Lindisfarne seemed to brush the rawest of nerves in many British people of this time. I’m not sure who might qualify for the present day title of “people’s band” in Britain – the Arctic Monkeys briefly came nearest to qualifying, and Mumford and Sons most certainly do not qualify (do you hear their songs being hummed on the bus, or in the pub?) – but Lindisfarne assumed the role of people’s band over the period 1971-2; Fog On The Tyne was one of the largest-selling albums by any British act released in 1971, and took its time climbing to the top (reviving its previously uncharted predecessor Slightly Out Of Tune in the process). The sepia-pink cover struck its own chord; an engraving – real or fake, it doesn’t matter – of Newcastle as its inhabitants might have known it in the days of Jane Austen, a peaceful but defiantly working-class city, and there is that same air of quiet defiance about the group’s music.

“Meet Me On The Corner” was the album’s big hit single, set in a square bass drum and harmonica dance pattern, and musically slightly reminiscent of “Mrs Robinson.” Singer and mandolinist Ray Jackson – you may remember his vital contributions to entry #99 – speaks to us about dream sellers (because “dreams are all I believe”), ways not of escaping but ways of examining his own reality far more happily (“Lay down your bundles of rags and reminders/And spread your wares on the ground”). The harmonies on the choruses, as elsewhere, are strongly predicative of the Electric Light Orchestra, but Alan Hull’s staccato Gilbert O’Sullivan piano intensifying the song’s harmonies on its first chorus takes us decidedly back down to earth, Jackson’s harmonica puffing ceaselessly like the most determined of trains.

“Alright On The Night” is far more intense, however, as one would expect from its writer, Alan Hull (generally, Hull writes the album’s darker songs and Rod Clements the lighter ones); he shares vocal duties with Jackson and Si Cowe and is palpably angry: “Can you tell me exactly what it is about me that’s so unclean?” he protests over a deceptively laidback “Maggie May” setting. “Take that stupid look off your face,” he continues, “Everything I say I mean.” He is not trying to repel his accuser, but instead inviting him to join him in his world (“Come and live with me in a cave”) – drummer Ray Laidlaw’s triple cowbells after the first chorus are like golden hammers striking an unknowing head. The choruses promise a straightforward good time, come out for a drink on Friday, that’s all we ask of you. The song’s subtle rhetoric persists – the guitar/mandolin interlude after the second chorus, Clements’ bass roving around the periphery of the men. The mood is almost one of a pastoral, provincial Stones, but there is another unexpected comparison which comes to mind (and with which Lena came up) – to which I will return shortly.

“Uncle Sam” is Cowe’s song – his first – which Jackson sings in muted breath over quiet guitar, mandolin and organ. Words such as volunteers, uniform, frail, jail, hang and blacklist make it abundantly clear what world we’re in – the war is still going on – and Laidlaw’s drums circle the song briefly before landing, together with harmonica and piano, to set up a Band-like midtempo mourn. “Well, I’m goin’ across the border,” Jackson tells us – to Canada? Or is he in 1746, in his own doomed-to-be-repeated history? – and after his “Watch what happens to me,” there is a short pause before Laidlaw’s drums rain down on his head; he’ll be on the road if anyone wants him, and one reflects on how huge and inescapable a shadow The Band are continuing to cast over unexpected regions of music at this point; the multi-vocal/instrumental approach, the deliberate archaism (masking an unanticipated newness) – but even this anti-Vietnam song could only have stemmed from the docks of the North-East.

With “Together Forever” – written by the great St Andrews folk musician Rab Noakes – the group moves back towards good-time mode, but there is a deeper tinge of true happiness; they’re sitting on top of the bus, in the front (“watchin’ the people who don’t look like us”), they have no money, but what do they care? Jackson sings the song truthfully and moderately lustily, and the band cruises along behind him like the most becalmed yet confident passengers, even offering an ascending music hall guitar signoff; they are perfectly happy being who they are and what they are, where they are, and are keen to let you know this.

Hull’s “January Song” leaks back into wistfulness with its acoustic guitar and roving bass, or at least pretends to do so; yet Hull’s own voice veers between several strips of agonised – there is an unavoidable Dylan tinge to his tone but the guitar appears to turn to acid behind him; The Modern Man, losing his way, unable to reach out and touch anyone or anything, and Hull’s blanching beg for him to rediscover what he’s supposed to be here for (“I sometimes feel the fear/That the reason for the meaning/Will even disappear”). The song drifts into an extended chant of “You need me need you need him need everyone” – should that “him” be spelt with a capital “H”? – as Laidlaw’s drums finally kick in and Jackson’s mandolin strums its vivid way into the picture. It is immensely moving.

But Hull’s gloom scarcely lifts. I have been unable to find out exactly who Peter Brophy was (or still is) but again it hardly matters; he could be singing about T Dan Smith or John Poulson – central and crooked figures in the demolition of old Newcastle – or simply The Man; but Hull puts every shade and nuance of emotion, disbelief, grief and hurt into his multiple “You don’t care”s. His voice becomes steadily more animated and dissolute, crescending into rage before falling back into simple regret; the lyrics are post-“I Am The Walrus” cod-surrealism but the anger does not fade (unlike the near-sibilant harmonica which cushions Hull’s quieting fury at fadeout); is this what we came through the sixties for?

With “City Song,” Hull finally cracks; he has had it with “the city” as he is compelled to know it (“I’ve been too long travelling on your train”) and sends modernity (as he thinks it) towards damnation; “Your tatty tricks to me/Are now really rather lame,” he sings, and later adds, “Your music doesn’t speak – it swears.” From most other people this would come across as crass reactionism but he is clearly attempting to grasp for something deeper, a slipped loss he is trying to regain. “Back to the garden,” “country lady,” “magic children” – it remains so hard, so impossible, to run from the sixties. The harmonies come in on the second chorus and fill up the song like semi-distilled nectar. In “Passing Ghosts” – the ghosts get thicker with every song; this is supposed to be a good-time band? – Hull’s voice and melodic construct are strikingly similar to those of his contemporary Bill Fay (his “sleep with we,” for instance) and he ends by resorting to the phrase/incantation “Come together” (upon which drums and bass make a very belated entry), Jackson’s rivulet of mandolin tinkling behind his despair. His grave might be ready (and still), but in the meantime he wants to pass the time, like a pewter mug of beer, between himself and his fellow human beings. That might be all he ever wanted.

“Train In G Major,” another Clements tune, is sprightlier. If the Dylan comparisons are inescapable (Bob Johnston produced the record), with the train indeed coming slowly, the record’s central message is as red as its boiler; “Take me to some better place to be...Awwww, wow, tell me baby!” Hull essays a brief “Ballad Of Bonnie And Clyde” piano quotation. The harmonica provides the engine, the walking bass lays down the tracks, and electric guitar offers rays of sunshine shivers towards song’s end. We’re finally getting out of “here” – and it might not be a geographical “here.”

No, because the title track, which closes the album, says strongly and proudly that they’re staying right where they are, Hull’s spirit finally satisfied and approaching modest euphoria (he shares vocals with Jackson and Cowe). “Think I’ll sign off the dole!” he exclaims (with two wake-up cowbells in response). The verse/chorus sequences work on tension and release; is this the first song in this tale to deploy the word “presently”? But again they tell us that this is what they want – the crappy sausage rolls, the pub, themselves and their own kind; it’s what they know and clearly what much of their audience knew and craved. Harmonica, fiddle, piano and mandolin patiently work the song up towards a satisfying, mantra-like climax. Understand us, they are saying, and you might understand yourselves. And indeed, turning back to “Alright On The Night,” its lyrics and general melodic structure, if set to a different tempo and different instrumentation – not to mention a different decade – remind us of a Newcastle teenager who at the time was playing in a folk group called Dust. His name was Neil Tennant. “Everything I say I mean”? Whatever was going to happen to the likelier lads of Tyneside in times to come, this record, entirely lacking in side or irony, tells the people who needed to hear and know it: we are still all in this together, and in a much more touchable and workable sense.