Thursday, 12 August 2010

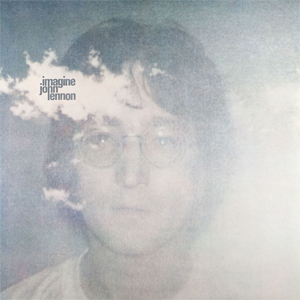

John LENNON and The PLASTIC ONO BAND (with the FLUX FIDDLERS): Imagine

(#100: 30 October 1971, 2 weeks)

Track listing: Imagine/Crippled Inside/Jealous Guy/It’s So Hard/I Don’t Wanna Be A Soldier Mama/Gimme Some Truth/Oh My Love/How Do You Sleep?/How?/Oh Yoko!

"An entire psychoanalysis of matter can help us to cure us of our images or at least help us to limit the hold of our images on us. One may then hope to be able to render imagination happy, to give it good conscience, in allowing it fully all its means of expression, all material images which emerge in natural dreams, in normal dream activity. To render imagination happy, to allow it all its exuberance, means precisely to grant imagination its true function as psychological impulse and force."

Gaston Bachelard, Le Matérialisme rationnel (Paris, Presses Universitaires, 1953; Bachelard’s italics).

His head is in the clouds, or if you look at it another way, i.e. on the back cover, his head is a mountain range. Climb him or drift through him; he’s not that bothered, except that he’s anxious that you’re there. In the CD booklet there are plentiful pictures of him, mostly with Yoko, on their Ascot estate; hanging out, goofing around, just being and living together. There is also a picture of him grappling with a pig, and that’s not necessarily another story. But the idea he’s trying to put across is: this is our world, and we feel that it should be yours too. If, of course, you want it. But then, was their world quite as perfect and peaceful as it looked?

We have reached the first century, and maybe Imagine’s indispensable happiness isn’t that far removed from the idyllically loving world of entry #1 (“Anything Goes,” “Our Love Is Here To Stay”), but its implications stretch much further and wider, even though most commentators have tended to overlook the record’s comedy. George has his sceptical garden gnomes, Paul has Linda, the kids and the farm, Ringo is there for and with everyone – but John has Yoko, and doesn’t particularly want anyone or anything more than Yoko, as he had already made abundantly clear on “God.” John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band doesn’t get written about here – in Britain, it peaked at #6 – mainly because not too many people at the time wanted to hear their leading sage tell them that the dream was over, and also possibly because not too many people had the stomach for some of the most (in)authentic rock ‘n’ roll ever recorded; the record was all about the singer opening himself up, screaming his therapeutic way out of self-imposed shutdown, and yet Lennon and Spector ensured that there is hardly a natural sound on the album; the singer’s voice is endlessly (apart from the word “Beatles”) double-tracked, processed, echoed, as are all of the instruments; primal his emotion may have been, but an important part of him was eager to press on with the future, as evinced by the same musicians’ work on Yoko Ono/Plastic Ono Band - their “Apple Jam” – where the feeling of delayed liberation goes somewhere past ecstatic.

By the time he came to put Imagine together, then, Lennon was unquestionably happier, although whether he had achieved total happiness is repeatedly questioned throughout the record’s duration. Having gone through the worst, he was prepared to express the same feelings and sentiments, but musically in a noticeably more approachable way, the residual rawness reused and sculptured into discrete songs. Certainly Lennon was keen that the listener approached him and his world – his and Yoko’s world, that is (interestingly, Yoko’s credit on this record is for “Whip and mirror”) – and indeed became a part of it.

Although “Imagine,” the song, is the album’s emblem – simultaneously a love song to his muse and a declaration of principles as they related to his world – the key song on the record is buried deep in side two; “Oh My Love” musically is the next logical step on from “Julia” – the succession of muse from mother to lover, now consolidated and celebrated – but in its hard-fought-for innocence is so touching that it could have crept from 1965 (think in particular of “Girl”), with its heartrending minor descents under the lines “Everything is clear in our world” and “clear in my heart”; this, above everything else suggested on the record, is what he wants. Everything may be clear in their world, but does that mean they can see through into the wider world, or vice versa? Given that the song follows straight on from “Gimme Some Truth” and is a sort of response to side one’s “Jealous Guy,” Lennon is not unaware of certain contradictions and constraints.

But the record begins with the manifesto:

“We may distinguish both true and false needs. ‘False’ are those which are superimposed upon the individual by particular social interests in his repression: the needs which perpetuate toil, aggressiveness, misery, and injustice. Their satisfaction might be most gratifying to the individual, but this happiness is not a condition which has to be maintained and protected if it serves to arrest the development of the ability (his own and others) to recognize the disease of the whole and grasp the chances of curing the disease. The result then is euphoria in unhappiness. Most of the prevailing needs to relax, to have fun, to behave and consume in accordance with the advertisements, to love and hate what others love and hate, belong to this category of false needs.

“Such needs have a societal content and function which are determined by external powers over which the individual has no control; the development and satisfaction of these needs is heteronomous. No matter how much such needs may have become the individual's own, reproduced and fortified by the conditions of his existence; no matter how much he identifies himself with them and finds himself in their satisfaction, they continue to be what they were from the beginning-products of a society whose dominant interest demands repression.”

(Herbert Marcuse, One-Dimensional Man, Boston: Beacon, 1964, Chapter 1: “The New Forms of Control”)

“Imagine no possessions. I wonder if you can.”

Broadly, according to Marcusianism, oppression arises when members of a society can only, or are only allowed to, define themselves by their relationship to the goods they make and consume, few of which could be said to be necessary to the promulgation of life. They may seem free, and all outward appearances might suggest freedom, but the actual choices available to them are drastically limited – “happiness” being equated with “keep quiet” (or, as that other sometime Marcusian Patrick McGoohan put it, “A still tongue is a happy life”). If we could somehow get beyond the façade, or trap, of consumerism, we might actually discover or rediscover the way we actually are as sentient human beings and live in better ways.

“Imagine” places itself in the canon of rock ‘n’ roll balladry – the echoing “Love Letters” piano, the Gene Vincent “yoo-hoo” ascent to the chorus (or second part of what is essentially an unconventional two-part song structure), the “Badpenny Blues” roll which connects the first section to the second, the voice whose quiet masks the suggestion that it is on the point of shattering (musically Spector makes it sound akin to Debussy’s drowned cathedral postcards) – all the better for Lennon to get his very firm message across. It all sounds reasonable to begin with – who could argue with peace or love, even in 1971? – but Lennon very subtly ups the ante throughout the song; now, he serially suggests, imagine no religion, no afterlife, no capitalism. Dylan disguised as Val Doonican. The video shows the song being played out on a white grand piano in an otherwise entirely empty room – too heavy for the bailiffs to take? – and at its close everything and everyone disappears, the question being: well, how do you propose to fill it? It was the subtlest proto-New Pop curveball he ever threw, so subtle in fact that Errol Brown could sing it with a straight face, in front of Mrs Thatcher, at a Conservative election rally sixteen years later and nobody, least of all Mrs Thatcher, got the joke, or the Fluxus strategic thinking (the “Flux Fiddlers,” in case you were wondering, were Torrie Zito’s string section, empathetically placid on the title track but rather argumentative elsewhere).

Lennon then systematically examines everything that his world is not. “Crippled Inside”’s ironic vaudeville trot comes from Ray Davies and its lyrical menu of façades from Dylan, with sharp acoustic guitar leading into Nicky Hopkins’ deadpan barrelhouse piano, then George Harrison’s descending dobro doubling Lennon’s doleful “You can call yourself the human race,” with Klaus Voormann and Steve Brendell’s double basses providing the old Bill Haley slap; Hopkins does a tie-loosened piano solo upon a sea of dubious dobro. Whatever you are, he says, with a nod to Smokey (“You can hide your face behind a smile”), I am not, and I can walk, talk and sense, so it’s not my problem.

“Jealous Guy,” however, is definitely Lennon’s problem; he admits that he is far from perfect, may even be a bit of a shit, but John Barham’s stentorian pillow of harmonium and Voormann’s delayed entry (after the first chorus) provide all the blankets that his vulnerability requires. He is clearly living the disgrace he is describing; his “shivering insi-IDE” chills the neck, his “Oh!” leading into the second chorus is a spur to himself not to tire of being humble, and Zito’s strings rise from the submarine yellow – having previously raised a quizzical eyebrow at the beginning of the third verse – to comfort Lennon’s bleeding “swallowing my PAIN.” It is its own apology and justification, recognising the existence of the fatal emotional duality at the heartless heart of “Love The Way You Lie” (that throwaway “Look out” near the end) but not being ground down by its presence. And as a rock ‘n’ roll performance, it is nearly peerless; did Elvis ever apologise so profusely in any of his songs, except when he was addressing God? He whistles to keep himself warm and Zito’s strings lead him by the hand, away from the centre of the lesion; love is not going to tear him apart.

But then we reach the Her Blues of “It’s So Hard,” the track which does more than any other to pave a way towards Cobain; the strings enter like a stern schoolteacher after the second verse and Lennon’s harsh, guttural vocals (is he trying to do a “rock” McCartney?) outrasp King Curtis’ sax. Cleaner than “Yer Blues” but considerably more pained, since Lennon confesses that even when he is with his Other, “Sometimes I feel like going down.” “You gotta SHOVE!” he protests. “But it’s so hard, it’s REALLY hard!” This distemper is extended into the long miasma of “I Don’t Wanna Be A Soldier Mama,” wherein Lennon has to steady himself within Spector’s hall of mirrors, Harrison’s drastically sliding steel, the acoustic sting of two Badfingers and even unto Mike Pinder’s tambourine (with Hopkins’ keyboards in for the distance). Veering, as with “Truth” and “Sleep,” somewhere between “Maggot Brain” funk and proto-dub reggae, rhythmically and emotionally, Lennon recoils and rewinds and gets the nearest this record gets to primal screech, going over things and people he doesn’t want to be, over and over, before reviving the “Oh, no/Ono” dichotomy from “Cold Turkey.” Then the multiple saxes of King Curtis burst in like a flood of Martian light, and upon Lennon’s “HIT it!” command double in number and intensity. The song becomes an endlessly chugging, intentionally clogged-up drone, Lennon’s post-Presley “WELLLLL!!”s (see also “Well Well Well” on Plastic Ono Band) devolve into astral baby gurgle and Curtis’ wraith of reeds takes the song abruptly out of its procession, with a brief electronic coda to close both song and side; one of the finest and certainly one of the final performances from Curtis, the only performer here who would not live to see 1972 – as with Mongezi Feza’s contributions to Wyatt’s Rock Bottom, he seems to be offering us his last testament, not of course that he could have known.

Side two – on a record allegedly about utopia – does not let up, at least not in the first instance; “Gimme Some Truth” has some of Lennon’s most splenetic vocals on the record, again launching himself against Tricky Dicky and his imitators; and is this the first appearance in this tale of the word “chauvinist”? Trying manfully to shatter the consumer wall (“Ah-ah-UHH!!,” just before the reprise of the first verse), Lennon roars and grunts and spews. Even Harrison’s solo – and is George’s work throughout Imagine the summation of everything he was too polite to say on All Things Must Pass? – splutters and vomits. The song is discreetly faded at the point where Lennon’s howls become screams; no need to overstate the obvious.

The bipolarity continues. “Oh My Love” sets out his world as he and I am sure not he alone sees it, but then he smacks back into the “other,” bigger world. “How Do You Sleep?” starts with a quick Bonzos Pepper intro pastiche, but the most notable thing about the long-expected McCartney demolition job, “Yesterday”/”Another Day” jibe included, pretty face and muzak jibes pretty drastically underlined – even though, as already demonstrated, McCartney’s relevant Ram songs were doing little more than telling Lennon that those days were over and didn’t you want them over anyway? – is how Zito’s strings circle around Lennon’s spleen before engaging in something of an argument with him (do you really want to go this far, they appear to be asking him). Harrison’s solo is more finely articulate, talking without saying anything, yet saying everything George needs and wants to say and with a good deal more dignity than John, although dignity is clearly the last thing on Lennon’s mind here. The song’s grind actually owes a good deal more to T Rex than anyone else – again, that no man’s land between funk and reggae – and Lennon’s primal warm-ups at the fade are contained by Hopkins’ decisive “Engine Engine Number Nine” Fender Rhodes solo.

The sadder and soberer side of the coin is laid out on “How?” Set up as an active dialogue between Lennon and Zito’s strings (with Voormann’s bass sitting on the fence), the string figures defiantly remind us of “The Long And Winding Road” but Lennon’s philosophical apology – to himself as much as to Paul or anyone else – reminds us that the road never was that straight; here he slowly lets it all out, amidst the pauses and hesitations which dot the song like an abstract highway painter. “Sometimes I feel I’ve had enough,” he states, blankly. “How can I have feelings when my feelings have always been denied?” he rhetorically asks himself (extending that “denied” into thirteen syllables). “How can I give love when love is something I ain’t never had?” (another baker’s dozen of syllables for that “had”) – but wait; isn’t he supposed to be happy, with Yoko? “How can we go forward into something we’re not sure of?” Where is that “home” again?

Well, it’s where he’s been, not where he’s stuck, since the clouds majestically lift on the closing “Oh Yoko!,” and suddenly we’re in the colourful world of the jauntier Van Morrison. It doesn’t matter whether he’s dreaming, or shaving, or imagining himself as a cloud; she’s the reason he does anything, and he is finally so, so glad of it. His “All right…RIGHT!” near signoff rounds the “Revolution” dilemma, and the last voice we hear is his harmonica, which he carries on blowing as the rest of the band disappear down the road, just as he did on “Love Me Do”; the circle squared. And finally, Imagine, despite all its expressed and inexpressible pains, finds John and Yoko in as happy and perfect a situation as we are ever likely to find them; yes, they can’t stay at Ascot forever – but don’t we wish, not so secretly, that they had done? – but right now, in the autumnal 1971 now, it’s all as good as it could be expected to get, and the simple question asked throughout this disguised folk record is: does the free faculty of the mind even need Ascot? It just needs us…all of us. The answer remains awaited.