(#71: 20 September 1969, 2 weeks)

Track listing: Had To Cry Today/Can’t Find My Way Home/Well All Right/Presence Of The Lord/Sea Of Joy/Do What You Like

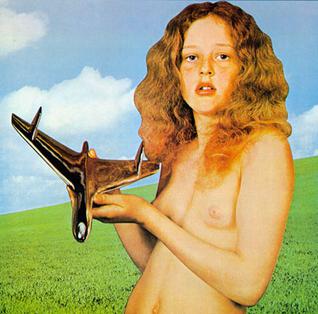

There are three more albums to go in this tale before the sixties end and as well as the sense of curtains being pulled down, there is also the sensation of new curtains being pulled open, or at least the desire, the craving, for a future, even if no one yet knew what that future was going to look like. In many senses there was the feeling that few of the survivors wanted to continue being what they had been, who they were, in the sixties. The Plastic Ono Band, for instance, had already begun to record and gig, and throughout the latter half of 1969 Eric Clapton was its guitarist. Did Clapton really know what he wanted to be in the seventies? He had tired of Cream and their epic jams, had succumbed to the influence of Big Pink and wanted to return to the (superficially) simpler process of playing well-written, thought-through songs as a member of an integrated and infinitely less pressured band; in his case, as with many others’, we can take “less pressured” to be synonymous with “less famous” or even “anonymous.” Why else would the first and only Blind Faith album appear without any indication of the group’s name on its cover? You bought the word of God blind and expected revelations. There were still enough believers to send the album to number one in both Britain and the States on trust alone, and although a vague frost of disappointment settled once the mist of belief had cleared, the record has proved to be surprisingly revelatory in other senses.

In truth Blind Faith were practically over by the time the album came out, but the experiment was perhaps always meant to be shortlived. In 1968 Clapton had unsuccessfully lobbied for Steve Winwood to join Cream, and after that group broke up, and Winwood had put Traffic into temporary cold storage, he was keen for the pair to continue working together. Winwood suggested involving Ginger Baker in any new group; Clapton was dubious since the last thing he wanted was Cream 2 (or The New Cream) but Winwood prevailed, insisting that Baker would be amenable to their new ideas. Bassist and violinist Rick (or Ric) Grech was recruited from Family to complete the line-up. They made their live debut as support act at the famous Rolling Stones Hyde Park concert on 7 June and were well received, although Clapton was disappointed with the group’s performance. They then did some touring abroad but, as what was essentially a jamming band, the lack of new songs required the resuscitation of old Cream and Traffic favourites. Hence both Clapton and Winwood found themselves in exactly the same situation from which they had attempted to escape; a “SuperCream” blowing idly to unquestioning thousands. One of their support acts in the States was Delaney and Bonnie, a far less complicated and considerably more enjoyable affair for the guitarist; Clapton began to hang out with them, eventually “joined” them and their backing band would subsequently mutate into the basis of Derek and the Dominos. Wanting nothing more at this stage than to be “Derek,” Clapton left the running of Blind Faith more or less to Winwood, and the band soon folded, the other three members teaming up with Denny Laine and many of the great and good of British jazz-rock in Ginger Baker’s big band Airforce before Winwood reconvened Traffic (with Grech on bass) in 1970.

So the Blind Faith album stands as a singular statement, necessarily inconclusive but a fascinating document of the various strands which British rock and jazz (and, via the transatlantic work of Jack Bruce, John McLaughlin, Dave Holland and others, also involving American jazz and rock) were busy interweaving at the time. Its opening track, “Had To Cry Today,” proceeds along a standard, Cream-like mid-tempo blues lope, but Winwood’s anguished lead vocal is clearly coming from a different place altogether, as indeed are the more complex harmonies into which the song quickly devolves. Despite Baker’s emphatic tom-tom work, the overall feeling is that of a more relaxed, less rushed Cream, and since the song (as with three others on the album) is Winwood’s it is clear that his is going to be the dominant voice here; he already seems to be getting ready for the adventures of John Barleycorn Must Die. Nevertheless Clapton opens out the song with his first solo; anxious, concerned, tonally very Hubert Sumlin (see the six head shakes of bending A notes halfway through). Winwood returns to see the song out, or so he thinks; his swooningly distant vocal on the penultimate chorus (“But you want every ONE to be free”) seems to lean back into a 1967 which hasn’t quite been left behind. The song resembles a more considered take on the riot-craving angst of “Something In The Air” (“The feeling’s the same as being outside of the law”) but Clapton buzzes moderately angrily under the final chorus and after a brief backwards loop begins to solo again, this time in duplicate; one guitar continuing the previous hurt, the other offering snappier, sharper Buddy Guy lines (if we take BB King’s Lucille as the template for the former, then this represents a masculine/feminine struggle). The song then stumbles into non-being with ambiguous closing harmonies, a resigned drum roll and a pondering bass wandering into the fog.

“Can’t Find My Way Home” is the record’s, and 1969’s, key song. Many of the hit songs which found their way into the charts towards the end of that year captured the awkward struggle of survivors from an unspecified disaster, trying to feel their way towards anything or anyone that might represent a home; think of “Reflections Of My Life” or “He Ain’t Heavy, He’s My Brother” or even “Two Little Boys.” There will be more crucial songs in the year’s two subsequent remaining number one albums but none quite captured that quietly shocked dissolution which Winwood articulated with such perfect imperfection. The quietest and briefest song on the record, it circles around its uncertain D major centre, rotating to C major, then to a heartbreaking B flat minor and finally back to D. “Come down off your throne,” pleads Winwood, his voice shaking on the phrase “You are the reason” as he clutches at the most visible straw in the clouded desert. A far cry from the confident trainee duende we heard two years previously in “I’m A Man” – confident enough to duet/duel with himself, and sharing the same producer, Jimmy Miller – Winwood has returned to a premature second childishness, desperate to stave off the merest oblivion. His exhausted traveller’s whimper – “And I’m wasted and I can’t find my way home,” the “can’t” very carefully pronounced with an estuarian “a” – is the most affecting and chilling moment in any 1969 music. Behind him, and around him, the band busk like a broken-down beat group, Baker’s supplementary commentary on (toy?) cymbal and rumbling tom toms particularly and subtly pertinent. Winwood turns his lament into the sustained, wordless howl of a bereft wolf, the noble warrior who has forgotten how to walk, perhaps even how or why to dream. He too sees the bad moon rising and realises that the only way to survive may not be to go back, but to press forward.

But then, when all seems lost, it is useful to remember where one started from in the first place. If Baker’s terminal steam train hiss of cymbals at the end of “Can’t Find My Way Home” signified that “rock” had run out of power and ideas, the group take that as a signal to go back to the beginning – to Buddy Holly (and interestingly Grech did some time in the Crickets in the early-mid seventies). They tackle “Well All Right” as a benign Southern fried boogie with a slight reggae lilt, although the stroll is framed by two agonised passages of Canterbury-type guitar/rhythm unisons more in keeping with Caravan (or perhaps Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac) than Cream. In between these troughs, Winwood is clearly leading the way, his phased piano and Hammond organ giving way to a couple of fine piano solos, the second (following the second unison statement and the false amiable ending) notably freer and more joyous, before Clapton finally adds comments of his own.

“Presence Of The Lord,” however, though sung by Winwood, is the only Clapton song on the record, and it is his moment. Beginning with solemn organ and processional rhythm, the influence of the Band is evident in every pore of the track; Baker’s gravely stentorian drums bearing a marked resemblance to those of Levon Helm, with patiently rolling ripples of Richard Manuel piano (over further tapestried layers of organ, piano and guitar). Throughout Winwood sings Clapton’s words of rebirth (“I have finally found a way to live”) with great, if precarious, authority. The unusual harmonies which underscore the second half of the second line of the second verse pave the way for a gradual loosening of the music. Winwood intones the pivotal, climactic “Lord” in a strangely uncertain (as though undecided, having second thoughts) pitch before Clapton and Baker blast off at double speed, Clapton issuing one of the most furious solos he has ever recorded, as though he had been waiting throughout the rest of side one to unleash what he felt, thought and wanted. He eventually retreats, wounded and angry, back into the fabric of the song but the pitch is eventually raised again with Winwood’s shrieking voice and Clapton’s icepick of guitar maintaining a mutual scream of release before Clapton appears to splinter into a million pieces at the song’s end, akin to a broken crystal ball displaying an unwanted future.

“Sea Of Joy”’s hard, clenched-teeth intro is abruptly succeeded by a return to a pensive acoustic folk mood, Winwood still in the pastoral fields of 1967 (“Following the fragments of the skies”). But then he suddenly explodes with a rare fury, shouting the line “AND I’M FEELING CLOSE TO WHEN THE RACE IS RUN!” as though to remind everyone that he is still approaching the end, or an end. He is questioning everything – the line “Once the door swings open into space,” is an accidental reminder of that other 1969 “Can’t Find My Way Home” variant, “Space Oddity” – and then an additional toughness is called in with Clapton’s dramatic entry. In his rhetorical intoning of key words such as “CONCRETE” and “ALL BECAUSE” (the latter phrased, possibly unintentionally, to sound like “OVERDOSE”) Winwood can even seem peculiarly reminiscent (or prophetic) of Peter Gabriel-era Genesis; his voice is piercing in its pain.

But then the song relaxes its tension, settles down to a nucleus of organ, electric guitar and Grech’s very Rick Danko-like violin, gradually multiplying like rose petals. We catch the bid “set sail” from Winwood and as Baker’s tom toms become more intense are also put in mind of that other 1969 nautical idyll (albeit in reverse), Procol Harum’s “A Salty Dog.” The song eventually disappears into ribbons and laces of quietening violin.

Baker’s “Do What You Like” at almost fifteen-and-a-half minutes is the album’s big jamming setpiece, but unlike countless subsequent examples does not sound forced or ponderous. Proceeding at a relatively brisk 5/4 – exactly like “Living In The Past” but with astral multitracked vocal harmonics taking the place of the flute – Winwood with a bright longing sings Baker’s very 1969 advice to open our eyes, take a look, get together etc.

Then the group settles into a groove; Winwood’s opening, hymnal Lowery organ solo rather unexpectedly takes us to the land of the Mike Ratledge/Robert Wyatt Soft Machine (while the song’s sentiments also correspond with those described throughout Kevin Ayers’ contemporaneous Joy Of A Toy, and the music’s sense of space provides a signpost to Miles’ also contemporaneous Bitches’ Brew). Clapton then comes in with a relatively restrained solo (actually sounding remarkably like the John McLaughlin of Extrapolation, and even more remarkably, if less surprisingly, like the young Carlos Santana); he is effectively a support player on this record, content to provide due service to the songs, but unafraid to express himself precisely as and when needed. Grech then gets his bass solo, which finds him in a Jimmy Garrison mood – pensive out-of-tempo meditations, double strumming – while Baker carefully traces his progress with nautical bells of cymbal chimes followed by slightly more pronounced snare rolls.

Meanwhile, odd, disjointed titular vocal chants fade in and out of the background. Finally Baker takes over for his long solo, patiently building up from quiet brush strokes via Cozy Cole/Big Sid Catlett paradiddles through Elvin Jones snare fusillades to the expected Max Roach/Tony Williams explosion of interdependent tom toms, cymbals and bar line divisions. It’s a great pocket history of jazz drumming, which was no doubt its intent. The background vocal chants meanwhile reach their climax and Winwood’s blossoming, ripening organ springs out of the ground and guides the band back to the song.

After a fulsome rally of “Get together!”s the “YOU LIKE” voices turn unexpectedly harsh and fuzzed and the song dissolves into a glorious, atonal free ensemble which atomises over the course of an elongated fade, together with enthusiastic ad libs from (mostly) Baker (“What a run!,” “Get down!,” “Big story!”) into pointillistic pricks of stars, a sudden, reversing Mellotron chord and assorted dots of random.

The overwhelming impression of Blind Faith is of a Cream and a Traffic on holiday, stretching their limbs and minds, free of pressure to be anyone or anything. In its own way (doing as it likes) it indicates a purple patch of musical freedom and cross-genre fusion to come; whatever any of the participants thought of it subsequently, they sound as though they are having an absolute ball, while Miller’s subtly less-than-documentary production precludes mere jam session status – the record feels structured and genuinely adventurous. Most subsequent “supergroups” would miss this essential interactive quality, based on the always erroneous assumption (as any cricket or football coach would tell you) that putting the “best” players together would create the best band. Despite the anguish of its central song, Blind Faith displays a certain degree of optimism about the new times to come as they prepare to reopen the curtain. The remaining two curtain callers would, as we will see, come to drastically different conclusions, even if ultimately they were both looking at the same thing.