(Boris Vian, “Les Joyeux Bouchers,” 1956)

“The erotic lyrics of black blues, often very amusing and almost always perfectly healthy and full of good feeling, have been systematically deformed and exploited by small white bands composed of bad musicians (such as Bill Haley) in order to produce a sort of ridiculous tribal chant for the benefit of an idiotic public. The obsessional quality of the riff is used to put listeners in a ‘trance’.”

(Boris Vian, “Rock And Roll,” 1956, trans. Larry Portis)

“…the force of the new vulnerability blurs the old stance of arrogance and contempt.”

(Greil Marcus, review of Let It Bleed, Rolling Stone, 27 December 1969)

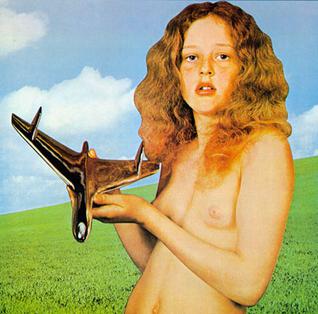

The Robert Brownjohn sculpture on the cover sums the time up, so accurately in fact that he remembers to include a clock. There is also a tyre – with the potential for burning – a pizza and a film canister. Above all this is a cake, reportedly prepared by the young Delia Smith, featuring the figures of five lovable mopped tops which never quite represented the group; right at the bottom, petrified by the imminent interchange, a long-playing record, with five unconcerned faces adorning its blood-red label. Next to it is an antique gramophone arm and needle, and I leave you to determine your own analogies there. It is as though the weight of the sixties is set to detonate, release, collapse on the Rolling Stones. After all, who built all that stuff up in the first place?

The rear cover demonstrates the inevitable outcome; all has fallen, the record is shattered and the only ingredient which remains intact is Delia’s cake. The five figurines are slacking around in a right unfit state – but one slice has been neatly cut and taken from the cake. The integral piece, now missing.

Consider the four Beatles, crossing the road and never to return, at least not together; they have the weight on them (“Boy you’re gonna carry that weight!”) but appear to wear it lightly. The Stones, in contrast, appeared to will the weight to crush them, squash them. But then all of the Beatles had managed to survive until the end of the decade.

It was, of course, all about appearances. “HARD KNOX AND DURTY SOX” the cover exclaims at one point. “THIS RECORD SHOULD BE PLAYED LOUD” it commands at another. This is not the language of mourning, nor it is particularly indicative of disguised grief. As far as this tale is concerned it is the last word of the sixties but there is nothing in the record’s riverrun grooves to suggest that the group wanted it to be anybody or anything’s last word.

The Stones have been absent from this tale since mid-1966; unlike the Beatles, they did not score automatic number ones – there is little in the blood of Satanic Majesties or Beggars’ Banquet to attract the love of Arbroath grandmothers. Yet, despite the loss of Brian, they sound and feel in far better shape than the Scousers as the seventies beckon; where Abbey Road is largely midtempo, somewhat gloomy and halflit in its introspective retrospection, Let It Bleed, despite the tracks which open each of its sides, is intent on living, on colour and interaction. Given that most of the songs were recorded by what was basically a four-piece band – newbie Mick Taylor turns up unobtrusively on a couple of tracks but otherwise Keith takes care of all the guitar stuff - the dynamics are pretty dynamic. They sound as though they’re having a better time than the Abbey Road inhabitants. The dream is over? Sod that; the Stones were and are businessmen and, despite the wreckage of Altamont a fortnight before the album’s release, were determined to keep the group going as well as keeping an eye on any future branding opportunities.

The common vision of Let It Bleed as era-terminating apocalypse is of course framed by “Gimme Shelter,” as uncompromising an opening track as to be found on any major artist’s album of the period. Guitars shiver, more in recognition of Buddy Guy than Hank Marvin, wordless voices cry from a not-too-remote wilderness, producer Jimmy Miller’s Latin percussion slithers like a tethered cobra (though they might have been recalling the washboard from a previous lifetime)…and then Watts and Wyman confidently set off a rumbling, hustling strut of a rhythm, topped by Richards’ wanly weeping guitar and Jagger’s harp, quite unlike anything we’ve heard on any of these 1969 records. There is anxiety, for sure – Jagger’s “Lord, I’m gonna fade away” is a bleached-out contrast to the ebullient certainty of “Not Fade Away” barely half a decade earlier – but this plea for deliverance, for harbour, is performed with the steel will of Colditz tunnel diggers. Note, for instance, how the song’s emotional emphasis relies on the repeated cries – or strokes – of “KISS away” more than “SHOT away,” even as it makes it clear that the faintest and most perilous of lines divides one from the other; somehow Watts’ insistent snare makes the song’s prowl resemble a kiss more than a shot.

Well, it’s almost full in its confidence – but then comes Merry Clayton, the dramatic shot of blood injected directly into the song’s coarsening arteries. While the group are clearly exulting in the prospect of destruction as they plead helplessness, Clayton’s burning ray of ice manages to cut through all the cake’s layers and provide the voice towards which all other 1969 dreams of escape and end had been groping. “Rape, murder!” she shouts before crying, twice, “It’s just a shot away!,” with so much intensity that the false upper register of her voice cuts into the song and generates real blood. The second “Rape, murder!” is midway between cry and scream…and the third is untranscribable, the terrible, ICBM-piercing howl that no amount of pastel-shaded blanket covers could shield, that threatens to haul down the curtain into hell and everyone’s life with it. How does Jagger respond to the latter? With an enthusiastic, enlivened whoop of joy – you got there, baby, you reached the grail only to find scattered blood. The end of everything? Bring it on! Still, as so much of 1969’s music doesn’t, “Gimme Shelter” stares the sixties full in the face and dares it to say it’s wrong, and despite the carnival whoops there is an uncommon intent to face up to some sort of responsibility for the future, to allow the possibility of a collectivity, based on the knowledge that, in the approaching age of me-ism, no one is possibly going to be able to get through it alone.

After that explosive opening, the record settles down to slightly more laconic business. In its original Robert Johnson version, “Love In Vain” is one of its century’s (and its author’s) most despondent songs; he’s taking her to the station, helpless to prevent her from leaving him (“I followed her to the station” rather than “walked with”), and when she’s gone he is as lifeless and abandoned as a gnarled gatepost. The Stones, however, have other ideas. Wisely deciding to lower the tempo and volume rather than outdo “Gimme Shelter,” their reading drifts into our eyesight as though reclining on a raft, acoustic lines soon giving way to a querying electric guitar (after Jagger’s second “station”). Clearly influenced by John Wesley Harding in both delivery and approach, Jagger bites down hard on the ends of each couplet (“Statioooooonnnnn,” “Haaaaaaaand”) but his lament of “love in vain, love in vain” is almost shoulder-shrugging in its offhandedness. She’s going; am I really that bothered?

But, as Jagger gargles “eyyyyyyyye” in the second verse, Watts makes a discreet entry, and as that verse concludes, Ry Cooder’s mandolin miraculously trickles into the song’s slipstream, furnishing the springwater of life with his busy solo; there are responses of deep currents of echo from Richards’ sighing, treated guitar. Following a slight pause, Jagger sets to business with the song’s payoff: “The blue light was my baby…the red light was my mind.” Angel versus Satan, again, and no prizes for guessing who’s won, even though the fervent caverns of guitar and mandolin heavily (or lightly) suggest the former. There is an expansiveness in “Love In Vain”’s arrangement which indicates a path towards the surprising elements of gentleness which would adorn some of the group’s best seventies work.

The Dylan influence (together with the less obvious influence of “The Universal” by the Small Faces) persists throughout “Country Honk,” a purposely lax acoustic take on their single “Honky Tonk Women.” Framed as a field recording, complete with bookends of studio chat and rhetorical car horns, the group, accompanied by the great bluegrass fiddler Byron Berline and “Nanette Newman” (see below) on backing vocals, together with some fittingly languid slide guitar from Mick Taylor, appear to be sitting, beaming, atop haystacks; Lena drew a comparison with the contemporaneous American country music and variety TV show Hee Haw – a mixture of “cornpone humour and fine fiddling,” according to her – and that air of amused slackerdom is very much evident here, even though Jagger’s central lyric becomes more accusatory than the single; now it’s “drink YOU” rather than “drink HER off my mind.”

“Live With Me” is the album’s first unexpected nod to Motown, with chattering guitars (Taylor and Richards) and a firm Benny Benjamin beat from Watts, but it soon dovetails into what becomes a template for seventies Stones rockers, most notably “Brown Sugar” (complete with Bobby Keyes tenor solo). Against this, Jagger does his wickedest best to persuade his hopeful Other not to take up slack with him, his scenario being that of the previous album’s wrecked/strung-out banquet, his helpless servants, flipped chauffeur, the shot water rat and fed geese, all decaying and proudly, even though there is a hint of prurient offence about his “harebrained children” with “earphone heads.” Yet there is a what-the-fuck swamp of good cheer about the song which carries the listener along; hear the upward piano swoop (Leon Russell and/or Nicky Hopkins) which furnishes an instant, starry stairway to the song’s first chorus, the way Keyes’ tenor blurbs out of Jagger’s “grrr!,” Watts’ suddenly aggressive cymbals (following Jagger’s “and when she strips…”). And don’t those “Whoo!”s remind us of somebody who’s come before?

The first side ends with the title track. Introduced by a guitar burp from Richards, placid acoustic guitars set the tempo before being augmented by Watts’ drums, Ian Stewart’s boisterous piano and Bill Wyman’s distant autoharp. Assuming a Southern States drawl on his “someone we can lean on,” Jagger sounds as though he’s auditioning for The Band, and the song’s general, patient forward thrust again reminds us of how vital a light the latter cast on this year’s best music. As Jagger gradually ups the ante (“…there will always be a space in my parking lot/When you need a little coke and sympathy”) the music picks up, Richards’ electric guitar again shivering. “Yeah!” exclaims Jagger happily. “Dirty, filthy basement” he beckons rabidly, as though offering continuous ninety-hour sex in all conceivable and inconceivable positions. Stewart moves into Pinetop Perkins mode, Jagger’s voice(s) now bleeding out of the bar lines. “We all need someone we can BLLLLL-EED on!” he cries, triumphant, and now, once more, the spirits become more wild than high (“ALL OVERRRRRRR!!!!”) as Richards’ clucking rooster of a guitar interlocks with Stewart’s boogie-woogie bounce and Watts raises his cymbal and snare bashes to Orange Alert level. The song bangs on and on towards its extended fadeout, the group doing their damnedest to convince themselves that they mean it – and, again, they transcend notions of façade and make you believe them too.

Side two begins with “Midnight Rambler” and the invention of Status Quo; that bustling lope of all-landing-on-the-vaulting-horse-at-the-same-time guitar riffery, plus Jagger’s plaintive harmonica and less than plaintive vocal, growling like the Wolf rather than howling (but then the Wolf, like Poltergeist, was always more frightening when he was quiet). All 100 Club, still there a touch of residual Anne Boleyn Secondary Battle of the Bands.

But then something else happens. Watts leads the charge from shuffle to harder rock attack, then with Wyman accelerandos into double-speed. Behind the rhythm lurks Jagger’s vaguely ominous double-tracked chant, which breaks down into proto-beatbox skittles of syllables. Somewhere in the far background Brian Jones is bashing some unspecified percussion; that summer Jagger and Faithfull had looked up the I-Ching and the dice had spelled “death by water.”

Then the track just stops, or rather reduces, or intensifies, to a creep. We hear some guitar/harp calling and responding, rather sad, like a Last Post lament relocated in an unwanted land. Jagger hisses: “Well ya heard about the Boston STRAN-“ before Watts stops him dead with his slapped gavel of floor tom. Jagger’s vocal, perhaps more influenced by Eric Burdon than he cared to admit, gets more worked up as his protagonist’s targets and methods steadily become more extreme and explicit; he is now wishing to DEMOLISH the sixties, RUIN his time, and the duende overtakes him, as we hadn’t always expected it to do – note the near-missable reference to “he’s pouncing like a proud Black Panther.” Next to this, Jim Morrison plays like Malcolm Roberts. The band storms back in – as the Doors never quite had the authority to accomplish – and rages the song to a tumultuous climax before moving towards a fast recap, Jagger now inhabiting the werewolf, his damaged Hamletian groan of “dagger,” his crowning/usurping “And I’ll stick my knife right down your throat BABY!” Follow THAT, The Seventies.

And yet “Midnight Rambler” – at least in its studio incarnation; we’ll be returning to it presently - just misses the Johnsonian crossroads; it is scary and powerful but absolutely what you would have expected from the hemi-bereaved Stones of 1969, whereas its Abbey Road equivalent, “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer,” is arguably far more disturbing; the Rambler might be the Devil but he’s unmistakeably on his own (and there’s no mistaking his oneness), whereas Maxwell has cheering supporters (“Maxwell must go free!”) and his Junior Choice perky MoR setting perhaps betraying a mind more twisted.

“You Got The Silver,” sung by Keith because the Jagger vocal track got lost, provides relatively light relief. Again very much indebted to Dylan (especially Keith’s vocal stylings), its backward seagull guitar filters, set against a solemn acoustic strum, are sonically the album’s most (only?) experimental moment. The tempo is a stately, Clarence Darrow 4/4, although the song briefly picks up speed before bending down again. Its hard-won patience (“A flash of love just made me blind/I don’t care, that’s no big surprise”) is a marked contrast to the desperation of the “I Want You (She’s So Heavy)” Lennon; indeed, despite its bilateral side-starting apocalypses, Let It Bleed – the title itself perhaps a knowing nod to Let It Be (not yet released as film or record but common knowledge in the business) or (more pragmatically) to the Boris Vian lyric from which I borrowed this piece’s opening quote – seems to offer a greater acceptance of things as they are, or were at the end of the sixties; things are a mess, and one of us didn’t make it, but isn’t it better, more honourable, just to get on with things, and possibly even move towards mending them?

“Monkey Man,” the album’s sprightliest track, again beckons in the direction of Motown with its twinkling piano/vibes unisons and pronouncedly Jamerson bass (never underrate Wyman, who contributed both bass and vibes to this track), backed up by Miller’s exuberant tambourine. This rapidly gives way to a more aggressive front – Jagger’s rhyming of “pizza” with “lemon squeezer,” possibly a friendly jibe at Zeppelin – and the rhythm is deceptive and complex enough to stand comparison with 1967’s “We Love You.” Wyman’s vibes really punctuate the song’s arrangement, working well against Richards’ grittily-edged guitar, the latter turning into a series of rubberband twangs as the song reaches its apex. “I’M A MONKEEEEEEYYY!!” gasps/groans Jagger, again and again, until, as the song fades out, resorting to Barry Ryan-style dog barks. Lena immediately spotted a kinship with Magazine’s “The Light Pours Out Of Me”; although Devoto’s vocal on the latter is the epitome of raging restraint, there is the same, insistent focus on the bass as the song’s absolute fulcrum, an axis around which the rest of the instruments, especially the guitars, can wander almost at will. But there is an equal certainty in both of their voices.

The final curtain on this part of the tale is brought down by “You Can’t Always Get What You Want.” The group were perhaps inspired by “Hey Jude,” but were also mischievous enough to hire the London Bach Choir, arranged by Jack Nitzsche, to sing in pure tones of connections and footloose men rather than a more predictable gospel chorus. If the track’s value stopped at this joke, however, then it would have little intrinsic value; here, as with “Gimme Shelter,” the Stones look the sixties in the eye, wave it an assured goodbye, knowing that there is no going or coming back; not too worried about anybody’s funny papers or negotiations but wise and human enough to bid this age a knowingly sad but ultimately celebratory farewell.

Al Kooper’s mournful French horn and keyboards melt into Jagger’s gentle tale of the systematic decline of everyone he knows; the wineglass woman is unavoidably Marianne and the title track’s trompe-l’oeil (“lean”/”bleed”) is repeated as her hand, in the final verse, becomes “bloodstained.” Meanwhile, the “Mr Jimi” encountered in the queue at the Chelsea Drugstore is usually assumed to be Hendrix (Jagger’s fulsome “AY said!” couples with his chilling “and that was ‘dead’”) but actually refers to Jimmy Miller (“dead” being the stock expression they used when discussing something that they liked); still, the prospect of a bloody finish (or bloodier beginning to the seventies, as indeed turned out to be the case) is unavoidable in the verse’s prospects, even though Kooper’s angry organ roars out of that “dead” as if to proclaim in protest “I’m NOT dead!” to welcome the second chorus. The chorus itself switches between the upbeat (all the better to shadow the irony of the title’s words) and a more considered piano descent/pause to reveal the jewel in the wreckage: “but if you try sometimes, you just might find…you get what you NEED!” Here is the song’s real lesson; the idealism of the sixties is over, the total change was probably never going to happen, but this doesn’t mean that we can’t keep trying to change the things we can…and by doing so, who knows what, or who else, we can change? The “NEED!”s are chorused with gusto by the backing singers – Madeline Bell, Doris Troy and “Nanette Newman” (and just to bury any attempted apocrypha, the wife of Bryan Forbes, star of The Slipper And The Rose, Fairy Liquid commercials, &c., played no part in these sessions; the credit was a private joke but the singer in question was one Nanette Workman, a native New Yorker turned Quebec resident who has pursued a long and distinguished career in both music and theatre).

In the instrumental break we swim in layers of organ, piano, guitar and choir before Jagger’s “AARGH!” snaps everything back into focus (“AOOOWWWW baby!!”). His “bloodstained hand” may verge on the tearful but is immediately answered by Kooper’s deadpan barrelhouse piano. The climactic “just might find” is elevated by a three-part, symmetrical choral arc. High-rolling piano figures react towards Miller’s off-centre drum triplets; surprisingly, Watts couldn’t quite lay down the groove that the band wanted for this song in the studio and thus Miller sat in on drums. The summit is tremendous, the Bach Choir rising steadily towards an astronomically high peak – the parallel with “A Day In The Life” and the equivalent urge towards rebirth are both duly noted – and at their highest point Kooper’s organ thrusts itself into the song’s body and Miller’s drums swing the celebratory mood, running the record, the Stones and this story out of the sixties and into something that looks pretty solidly like a future. If side one of Let It Bleed documents a journey from rootlessness to home – from “Gimme Shelter” to “you can lean on me,” the dawning realisation that we must finally provide our own refuge – then side two sees the Stones pushing their own boundaries in the ways they knew how. Excursions like “Revolution #9” would have been utterly inimical to the way they worked, being a far more organic band than the Beatles; throughout the record one is struck by just how firmly they exist and thrive as a working band, even minus one key member. Unlike Abbey Road one does derive the feeling of four people in a room playing and interacting as a unit. But there is the same degree of determined hope, an iron will to continue to exist in a new decade, a knowledge that nothing and no one, save perhaps themselves, could ever stop them. And as “You Can’t Always Get What You Want” plays out, with yet more of those exclamation mark “Whoo!”s, we are finally reminded of where this tale started in the sixties, with Freddy Cannon, whooping and hollering this decade into being, with so much hope, hardly any of it diminished, virtually all of it strengthened.