(#66: 24 May 1969, 4 weeks)

Track listing: Girl Of The North Country/Nashville Skyline Rag/To Be Alone With You/I Threw It All Away/Peggy Day/Lay Lady Lay/One More Night/Tell Me That It Isn’t True/Country Pie/Tonight I’ll Be Staying Here With You

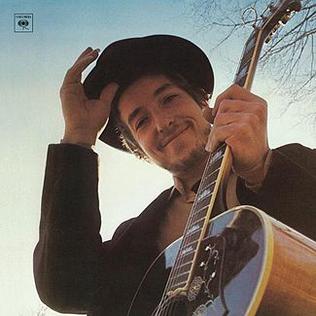

There is no front to his smile; he is bidding you a warm welcome to the morning to which you have awaken from your querulous voyage of dreams. Or perhaps the smile is rueful; he is bidding you a regretful farewell – the picture is taken as though viewed from the grave.

Many at the time thought that he had come to bury the sixties, as though John Wesley Harding hadn’t already given enough notice of where he was heading. An extremely brief – twenty-seven-and-a-half minutes – and extremely sprightly record of what was conveniently described as country music, even down to the involvement of Johnny Cash as guest artist and annotator, delivered to a somewhat confused audience who were feeling, or fuelling, the rage and discontent of 1969 and were impatient for answers, directions. And who were given an album of country music, still perceived by many Dylan followers at the time to be the enemy, the soundtrack of the oppressor, rather than the soul music of the poor white man (as opposed to “poor white man’s soul”), even though James Carr or Howard Tate could easily have performed “One More Night” or “Tell Me That It Isn’t True” as arranged and performed here.

Such misplaced grief was, of course, ill informed; after all, had Dylan not grown up with country music all his life, his ear to the radio in the Minnesota small town of his youth, listening to and absorbing many of the songs he would later broadcast on his Theme Time Radio Hour series? Furthermore, the keener ears had already picked up on what John Wesley Harding might imply, particularly those of Gram Parsons, a glam rock stud one continent and four years too early, who engineered the Byrds’ transition into Sweetheart Of The Rodeo and would presently unveil the Flying Burrito Brothers upon a largely unlistening world, making the links between the dual colours of Southern soul explicit. One could also add the not insignificant example of Aretha Franklin, another artist who had to travel from the North to the South in order to find and express her truer art.

More important than any of these factors, however, was that the Dylan of Nashville Skyline was now a husband and a father, looking to settle down, getting a little bored of the pressure, the renewed attention. He is, in fact, as happy as and probably happier than he looks on the cover; the album, despite its several essays on lost love, is likewise one of his happiest sounding.

It begins with a song we previously encountered on Freewheelin’ – and my venerable copy of Skyline states “Girl Of The North Country” on both sleeve and label, rather than “From” – but which is now delivered in a markedly less dark manner; indeed its centrally dark verse, contrasting the darkness of the night with the brightness of the day, is absent. Cash’s entry is a quiet eruption – although his justly honoured poem of a sleevenote is more overtly “poetic” than anything on the record itself – and his voice, slightly shaky but deeply warm, knows the ridges between “the edge of pain” and “the what of sane” instinctively. He sings “Haiiiirrrrr….” like a comb falling ecstatically through his lover’s locks and his voice onomatopoeically “curls and falls.” The song proceeds towards a ragged, last drink at the saloon singalong but Cash’s consummating boom of “remember me” reminds us of the seriousness underlying the apparent playfulness – a seriousness which Cash never relinquished, especially during the heightened spirits of his San Quentin concert, the album of which only just missed inclusion in this tale and in the course of which he nearly starts and then quells a riot. His adventure was that of a country perhaps fashioned for himself to stalk and record; never quite a rebel but never quite an establishment insider, politically open and ambiguous, a sui to the generis of his chosen form of expression. He was the Elvis who never had a Col Parker to say “yes” to, the Jerry Lee who had made his messy piece.

Then we get an instrumental, “Nashville Skyline Rag,” which Dylan largely gives out to the rest of his players to introduce themselves; these included Charlie McCoy on harmonica and guitar, fellow guitarists Norman Blake and Charlie Daniels, keyboardist Bob Wilson, drummer Kenny Buttrey, Pete Drake back on pedal steel and – crucially – Earl Scruggs himself, the man who as one of Bill Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys had pretty much started all of this, and who had lately played an indirect part in 1967 via his appearance on the Bonnie And Clyde soundtrack - on five-string banjo. The pace is bustling but good natured, and in Wilson’s piano solo we are even reminded distantly of, of all things, Don Ellis’ contemporaneous “Pussy Wiggle Stomp.”

The roll of “To Be Alone With You” owes somewhat more to the blues than country, but again Wilson’s piano joins the stylistic dots (with pointed electric guitar commentary), and there is a fervent air of activity which sets the scene for Elvis’ return to Memphis. Dylan provides one of the album’s best vocal performances; the shaggy dog downhill howl of “When I’m alo-o-one,” his octave seesawing hiccups of “al-WAYS THANK the Lord!”

“I Threw It All Away” is the first of the album’s great trilogy of love songs, and seldom has loss been expressed in popular music in such a beneficent manner; Scott Walker’s rendition, some three decades or so later, is intoned as from inside the grave, but Dylan tries to find light in this darkest of the album’s many corners. He knows he has lost her and that it is entirely his fault, but something – the tug of Wilson’s Hammond organ, the pull of Buttrey’s snare drum (most rhetorically distinct under Dylan’s “one who’s tried” at the end of the middle eight) – will not let him go under; there is an amiable determination for renewal, and early on in the song there is the Robert Johnson reference to mountains in the palm of his hand, the same reference revived in Hendrix’s “Voodoo Chile” and the Temptations’ “I Can’t Get Next To You”; this is Zeus, shrugging his mighty shoulders, settling back into Olympus to lick his wounds, but only briefly. There is none of the spite or bile to be found in earlier (“Positively Fourth Street”) times, but rather a resigned contentment, the acknowledgement of the beaten god.

Side one ends with the playful “Peggy Day,” a cross between the Ink Spots (the guitar intro) and the lighter-hearted Harry Nilsson (“Cuddly Toy”). Dylan has great sport with the song, even recalling Rudy Vallee on his rolling, up hill and down dale vibrato of a “loved” in the line “loved her all the same.” At the merest suggestion of sensuality (“Love to spend the night with Peggy Day”) Pete Drake, the secret prophet of John Wesley Harding, rears his pedal steel’s head in mild disbelief (“Even before I learned her name”). A sudden stop leads to a Fanny Brice vaudeville piano ending. Is Dylan sneakily having a joke at our expense?

Such vapid questions vanish approximately half a second into “Lay Lady Lay,” which I shall leave until the end; “One More Night” is a fine slice of Southern country-soul wherein Dylan leaves none-too-subtle indicators to his audience (“I just could not be what you wanted me to be”). Again, his love seems irretrievable, but he is unbowed – the what-me-worry shrug of his “Mo-on light” – despite the occasional sharp interjection of pain (his octave jump on the “high” of “wind blows high”). Wilson’s piano takes the song to a satisfied and satisfactory ending. “Tell Me That It Isn’t True” is cut from much the same cloth, and musically is most noticeable for Buttrey’s rattling, intense drums which cut into the middle eight and again towards the song’s finale. Things turn brighter with “Country Pie” – a title which, along with the song’s atmosphere, would hardly be out of place on the White Album – and again there is the flash of Memphis with McCoy’s guitar solo, as short and snappy as a lunching alligator, while Wilson’s piano roars elbow-wise up the keyboard at the end of each middle eight. Dylan again warns his listeners against surface interpretations – “Ain’t runnin’ any race” he sings at one point – but his joy is more apparent than any wariness, as witnessed in his “I won’t throw it up in anybody’s face” which he sings up and down the scale in the manner of Lonnie Donegan, prior to giggling through Jack Horner double entendres before the track fades abruptly, as though running off to catch the football game.

“Lay Lady Lay” is, however, one of the album’s, and indeed one of 1969’s, key songs (it was originally written for, but not used in, the soundtrack to Midnight Cowboy); its beautifully inevitable but wistful foursquare semitonal descent of a harmonic topline (and deceptive, since its chords are travelling in the opposite direction – A major, C sharp, G major and B minor), the key contribution of Buttrey, improvising on cowbell and bongos in between fills on his kit drums (the contrast is one between a waiting, ticking clock and a sprung-into-action dynamo, although the drums are considerably further back in the mix than the auxiliary percussion). Its unwavering focus on Dylan’s voice, too, reminds us strongly of the “new” Dylan we are hearing here, a sudden smoothness which is usually ascribed to the singer having recently quit smoking. It is the album’s most unnerving moment – and to whom, and of what, is he singing? The “big brass bed” seems more in keeping with Muddy Waters than Hank Williams – and why the switch from the first to the third person in the second verse (“Stay with your man awhile”) before returning to the first? Is this love illicit (“You can have your cake and eat it too”), or is the explanation simultaneously more complex and more simple?

The answer must come in the shockingly bold middle eight, where the band jumps into life as Dylan’s voice increases in volume and intensity. The first verse concludes with imagery which could have come out of 1967 (“Whatever colours you have in your mind”), the second brings everything back down to earth (“His clothes are dirty but his hands are clean”). But now he addresses his would-be Other: “Why wait any longer for the world to begin?” and then “Why wait any longer for the one you love/When he’s standing in front of you?” before the song settles back down, uneasily. He is in part standing outside himself, but in greater part is actually willing a sleeping lover to awake; “Lay Lady Lay” would appear to be a plea to awaken, to live, Cupid and Psyche with the roles reversed.

But just as John Wesley Harding concluded with the sated purr of “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight,” so does this album ride off with the smilingly serene “Tonight I’ll Be Staying Here With You.” In fact he’s shedding all of his baggage, perhaps all of his previous life, in preference of his renewed dedication to love – “Throw my ticket out the window,” he declares (“If there’s a poor boy on the street/Then let him have my seat!”); it’s all unnecessary now - this is all he craves, wants and needs. At the phrase “The love that a stranger might receive” there is a sublime, if temporary, key change, and Buttrey’s snare and tom toms close the door on the past definitively to accompany the line “I can hear that whistle blowin’.” Drake then re-enters with some heavenly pedal steel lines – wiring up Paradise’s switchboard – which luxuriate and cover the benign folds and curves of the song like the softest and deepest of bed sheets.

Nashville Skyline might seem the precise antithesis to the Moody Blues – a smiling reality superseding the demonic darkness of dreams – although many of its songs (including “Lay Lady Lay”) could have been performed by the Moodies. Furthermore, both records share an unshakeable conviction that love is exactly what we see and exactly all that matters, as emphasised in the key lines of "I Threw It All Away": "Love is all there is, it makes the world go 'round/Love and only love, it can't be denied." More to the point, however, is that the album marks the starting point for what would eventually come to be known as No Depression – Uncle Tupelo, Wilco, the Jayhawks and all points extending outwards, all of whom absorbed this record intently before setting off on their own adventures. Through the involvement of Norman Blake, we can also trace a line to O! Brother Where Are Thou? and thence to people like Gillian Welch who would draw quite drastically different conclusions from Harding and Skyline (amongst many other influences). If 1969 had already given us – or was about to give us – Dusty In Memphis, then Skyline is Bob in Nashville, but more importantly it is Happy, Contented Bob. Where were the anti-war protests, the calls to arms? Well, shrugged Bob, I gave them to you six years ago; weren’t you listening? The greatest lesson I have learned, he might have gone on to say, is to learn and feel how to live the happy and blameless life. Inevitably, given Blood On The Tracks half a decade later, this happiness and blamelessness would not be eternal. But for now the Worried Man is settled; and Lena drew a telling comparison with Wowee Zowee, Pavement’s “country” album (see the very Drake-esque pedal steel on “Father To A Sister Of Thought,” for instance) which drew similarly bemused responses from its audience but which in retrospect represents a clear and logical stage in the group’s development. It was the same with the Dylan of 1969, happy to go on Johnny Cash’s show, sing through a few old tunes, happy just to be happy. The message, like the smile, could not have been clearer.