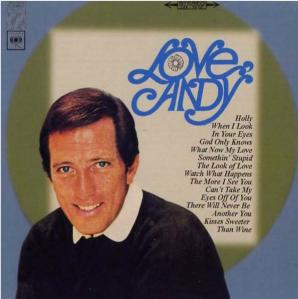

(#55: 15 June 1968, 1 week)

Track listing: Somethin’ Stupid/Watch What Happens/The Look Of Love/What Now My Love/Can’t Take My Eyes Off You/Kisses Sweeter Than Wine/Holly/When I Look In Your Eyes/The More I See You/There Will Never Be Another You/God Only Knows

“With the sun and the sea and the sky she remains”

(“Holly”)

Following a period of violent, vivid destruction there must always come peaceful, or at the very least quiet, reconstruction. Both the I-Ching and the Bible speak of water, steadily accumulating to form a flood, sweeping away the world that had previously and presumptuously been built upon it, leaving an ocean, a liquidity, for its inhabitants to start again. Similarly there has long been philosophical, psychological and theological talk about man’s love of and need for water, man’s inherent desire to begin again, to return to the waters of the womb which they once inhabited.

Were some such distant shore ever to materialise after anyone’s apocalypse its sound might not be dissimilar to Love, Andy. Few albums are so concerned with the eyes as primary means of communication within the love song; five of its titles make that explicit, not least “The Look Of Love.” But there is also the feel of a Ballardian terminal beach, the great wave patiently waiting to engorge it with a new, terrifying but liberating fullness. A feeling that the singer’s love must encompass, and eventually form, the whole world.

It has always been apparent that Andy Williams is not quite one of our everyday, amiable crooners. An early giveaway was his dubbing of Lauren Bacall’s singing voice in To Have And Have Not, but his voice has, if anything, always projected an asexual, rather than a specifically androgynous, spirit, somehow above the everyday cares of the planet it inhabits. Compare the great, brassy and percussive thrust and barely concealed sexual craving of Frankie Valli’s “Can’t Take My Eyes Off You” with the smooth patience of Andy’s, its daubed echoes of Sportsnight With Coleman brass, lithesome alto sax and subtle, undulating undertow of reeds offering perspectives reminiscent of another Andy W. He is simultaneously connected and detached.

Side one passes by relatively peacefully in the manner of the standard late sixties album of easy listening slow jams, designed to be played late at night to one’s hoped paramour with a diplomatic drink and tactfully lessened lights, and Andy’s lounge is undoubtedly an enticing one. Still, even from his opening reading of “Somethin’ Stupid” it is clear that this is not going to be a straightforward record; Nick DeCaro’s arrangement is very different from the double-headed Sinatra original, its opening flutters of Claude Thornhill reeds and woodwind easing into smooth 1967 strings. Both pace and performance could have come from an old school (or old Palais) dance band, the odd contemporary flight of flute notwithstanding, but the harmonic differences with the original are subtle and telling; no chordal diminution before “And then I go and spoil it all” but there is a lovely minor augmentation on the “before” which closes the middle eight. A choir steals in unobtrusively, a melancholy trumpet wanders through the melody like a regretful, decommissioned Army colonel, and banks of trumpets and trombones sigh in breathy concordance. One modest key change takes the song out into its wider drift.

With “Watch What Happens,” Legrand’s tune from Les Parapluies de Cherbourg, a strange but serene spaciousness begins to become apparent; the same moody trumpeter (the sleeve offers no clue to their identity, but here the trumpeter sounds far closer to Bunny Berigan than Herb Alpert) opens up the song, allowing Williams to ski over the elegant titular major-minor-major arch. A tenor sax distantly buffers the infinitesimal breeze and the general bossa nova glide reminds us of the new sense of space which Jobim and his Tropicalia successors brought to the picture of pop throughout this decade; the Sinatra/Jobim 1967 collaboration is required supplementary hearing here. Following a slightly awkward edit to accommodate another key change, Williams effortlessly covers the gap with one of many extraordinary, unbroken slow-motion yodels to his highest achievable register, without once using falsetto, and transcending matters of gender and notions of earth.

His “The Look Of Love” – also covered not long thereafter by Scott Walker, on the latter’s Scott Sings Songs From His TV Series – commences with a stately brass chorale. Again, Williams’ voice seems to float in a sense of gravity different from but compatible with the song, anchored by the slightly assertive brass figures which appear in the choruses. But his “Don’t ever go” blends seamlessly into a high string figure before the song pauses, and he offers three “I love you so”s as both voice and strings mesh into stasis, momentarily start again in cumulonimbi of doubt and the alto reappears as everything fades into strings so static they could almost be synthesisers.

“What Now My Love” is taken against a fingersnapping chain gang rhythm with emphatic guitar/bass/bass drum thumps and tweaks decorating Williams’ increasingly dissolute vocal (“I feel…closing around me”). With his “There’s the sky” he seems to be swallowed by the strings before he can utter “…where sea should be.” There are brass blasts from the next galaxy, the flute again, and then Williams’ double-tracked harmonies come into being. The song finally dissolves into inchoate murmurs in the aether, barely exists beyond end horizon. This record is not quite what it presents itself as being.

The side ends with “Kisses Sweeter Than Wine”; the same easy swing tempo as “What Now My Love” but a two-bass, octave-leaping figure which almost certainly owes something to Gil Evans’ “Las Vegas Tango” is a sturdier buoy. The song moves into straightforward swing for its choruses, but throughout, with the tune’s endlessly ascending key changes, Williams again seems somewhat detached from the life of the self that he is describing (“She had…mmmmm….kisses sweeter than wine” he hums, as if consuming his own life slightly faster than he is living it). The double-tracked vocals reappear in the third verse, the increasingly icy high strings in the fourth. The alto sax takes us out of side one, accompanied by a curiously Cale-esque clanging piano. The feeling begins to be engendered that if Brian Eno were producing an Andy Williams album it would not sound dissimilar to this.

Little of this, however, prepares us for the astonishing second side, during which Williams appears ready to leave this world altogether. “Holly” was written by one Craig Smith, then of the folk-rock group The Penny Arkade; he subsequently drifted off to India and to drugs, and when he came back in the early seventies it was as Maitreya Kali, under which name he produced a couple of highly disturbing albums whose chill spirits owe more to Manson than Roky Erickson before he drifted off into complete obscurity. Williams’ reading of “Holly” with its peaceful, patient acoustic guitar balanced by busier electric one-note picking certainly radiates something of the mystical, this “Holly” enters his mind but it’s no longer clear whether Holly is a woman or simply (simply?) a state of a disturbed mind. “With the sun and the sea and the sky she remains” Williams sings as the song and arrangement crescendo behind him before settling down again into unsettled pacific blues. With the closing proto-Echoplex guitar figures he appears to disappear from the landscape.

“When I Look In Your Eyes” is a song and performance so exceptional one forgets that it comes from Doctor Doolittle; a beautiful song whose aches – first accompanied by piano alone, then (in the second verse) by sympathetic strings – link Williams with Walker. His increasingly enlarging statements – “I see the deepness of the sea,” “Autumn comes, summer dies” – are sung in a manner so similar to Scott that it’s uncanny and the high voice/strings unison ending cries like a butterfly about to fall off the edge of the globe.

Williams then returns slightly closer to Earth with his radically altered readings of Chris Montez’ two radically altered readings of Mack Gordon and Harry Warren. In contrast to the cheerful claps and vibraharps of Montez, his “The More I See You” is taken as a slow, bluesy drift. There is a stunning moment where Williams’ sigh expirates and strings instinctively enter, anticipating the chord changes to come. An alto flute dolphin skates atop the beach-kissing surface, and those long, sustained, vibratoless notes at the song’s end would not be out of place on Eno’s Ambient 4: On Land. “There Will Never Be Another You” is more solidly swinging with uncomplicated 4/4 beats, seductive strings and a rather cheesy organ solo, but its momentary return to inspect the lounge is deceptive.

Because Williams’ reading of “God Only Knows” makes him a God. With Williams and Walker – which came first, Ohio or Iowa? – and with Love, Andy and Scott 2 in particular, the parallels and contrasts are now clear. Scott 2 began with wanting to be God and ended by being content to be loved. Whereas Love, Andy begins with smelling her perfume and thinking that being loved would be a nice idea, and ends….by sitting with God. It’s not entirely clear to whom Andy is actually singing “I may not always love you” or “So what good would living do me?” – and the album’s subtle passage from a song written by Carson Parks to a song associated with, if not strictly speaking written by, Van Dyke Parks should also be noted – but let’s consider; he wants the girl, gets her, loses her, immediately starts seeing someone else…but as side one becomes side two, the concept of Other becomes abstract; she’s still there, but far away, and maybe only a mirage. In finality the singer becomes the whole world, his love has to encompass the ocean and the sky, become the world – is Love, Andy a disguised religious album? – or at the very merest addresses the world. Williams sings “God Only Knows” – a song its author considered so holy that he encouraged his brother to pray before singing it – out of tempo, with Lincoln Mayorga’s majestic piano suddenly accelerating into a world-engulfing cathedral of strings and woodwind, screaming out its crescendi before dying down to a chimera of chiming bells and French horn foghorns. Huge, warm (if slightly chilly at times) and embracing, Love, Andy sees the pearly dewdrops’ drops coming on the horizon, constructs its own song to sing to all reigning sirens.