(#1: 28 July 1956, 2 weeks; 25 August 1956, 1 week)

Track listing: You Make Me Feel So Young/It Happened In Monterey/You're Getting To Be A Habit With Me/You Brought A New Kind Of Love/Too Marvelous For Words/Old Devil Moon/Pennies From Heaven/Love Is Here To Stay/I've Got You Under My Skin/I Thought About You/We'll Be Together Again/Makin' Whoopee/Swingin' Down The Lane/Anything Goes/How About You?

The song begins with a delicate celeste balanced against a gruffly amiable bass clarinet - she and he. He's been captured by her and he isn't quite sure what to do about it; he certainly betrays more evidence of wanting her than wanting to run away from her - his "so deep in my heart" is immediately answered by scarlet cushions of strings. Perhaps he's been hurt before - the missed chance in Monterey, the moon which keeps reminding him of mortality - and is reluctant to go back in, but the palpable nervousness in his voice suggests that he's been away from love for so long that it's going to take him some time to recognise its contours. He struggles with his "better" self on the surface - who "repeats, repeats in my ear" with all the nervous stress laid on the second "repeats" - but knows that rationalism ("Use your mentality") will be of little use to him now. The brass buttons which scream at him not to "STOP" indicate that he had better surrender and experience the renewed sensation of what might just be categorised as happiness.

We know from the instrumental interlude that he's going to dive in, like an Olympic hopeful poised on the board above the shimmering pool of strings. The pace picks up; an insistent bass trombone figure is subtly transferred to baritone sax, while the violins give three ascending harmonic steps. Silent, the man can't quite believe it's going to happen, but the inevitability of it all is pulse-quickening.

And then Conte Candoli's screaming lead trumpet ushers in Milt Bernhardt's solo trombone to break - indeed, smash - the song open as all doors seen to give way to ecstatic summers. Getting to grips with saying what the singer is yet too timid to say in words, Bernhardt embraces, fumbles with fortissimo relish - and there's no question where that phallic slide's going to end up. Taking the hint, the singer returns, mimics the trombone with a notation-defying ski lift of "IIIIIIIIIIIII..." to launch himself back into the song; now here is the confidence he'd been battling for; this time the "repeats" doesn't repeat itself but "YELLS" in his ear an orgasmic, extended "DOONNNNNN'T" - another moment which can't be adequately reproduced on score paper - before the song quietens down, dims the light in satisfaction and the singer's triumphant grin frames his ultimate "you" with a final string section question mark nestling up towards his neck; go on, just that one last crucial step...

Listen to that "IIIIIIIIIII..." or that "DONNNNNN'T" in Sinatra's "I've Got You Under My Skin" and you hear the hopefully beating heart of every smalltown barfly who ever fancied himself as a singer, every anxious club crooner, every seldom spotted teenager fantasising about launching themselves onto girls and the world, perhaps in that order - the desire and thwartable confidence of every pop singer who has ever dared to sing. In terms of how a child might grow up to be a man, of how to fashion what is inside them to present themselves to a world which might love them and ensure that other children and further humanity is possible - or simply in sheer terms of the ceaseless transformative capabilities of the voice in relation to popular song - Sinatra's "I've Got You Under My Skin" might be the first pop song I'd play to ears new to music, whether young or from outer space.

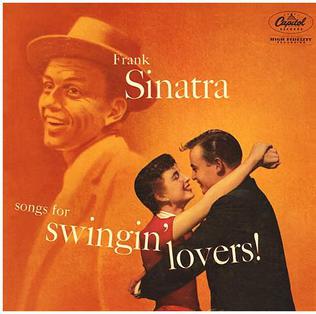

It was also one of the first pop songs to reach these ears. For this piece I am referencing the 1969 LP reissue of Songs For Swingin' Lovers!, in stalwart mono, bought by my father as an anniversary present for my mother and which has somehow ended up stuck in my collection since around 1981. Somehow it has always been there, a presence in my life. The sleeve depicts a fifties couple - who might as well have been my parents - joyfully embracing, with Sinatra grinning benignly down on them from top left like a Hoboken angel.

Everything about Lovers declares newness, a surprise when you consider the ancient pedigree of some of the songs. As an artful exercise in repackaging the old in new, hipper clothes, the album takes some beating; but it is very conscious of its heritage and how to avoid getting trapped in or by it. Take "Pennies From Heaven," for instance, a Depression era song of hope. In arranger Nelson Riddle's hands the song turns into a reminder of and farewell to that grievous past; the ominous introduction gives way, again, to that reassuring post-war celeste, Sinatra surfs on the additional "s" of "sunshine and flowers" and at the end the brass stick out a nyah-nyah tongue as though to say, you thought you could destroy us? Yet, on the closing, "How About You?," what on the surface sounds like a defence of the good things in life as defined against the rock 'n' roll thing whose waves were already lapping at this becalmed shore, Sinatra is astute enough not to make the song sound like a defensive gripe; he persuades us that Gershwin tunes and good books fortify a lived life but nicely undercuts his stance by referring with a wink to "James Durante's looks" which "give me a thrill" as well as the almost unnoticed "nu" he affixes at the front of "New York in June."

Of course, Sinatra was also making himself over anew. Following his career revival in 1953, his initial series of albums with Riddle at the helm were very clearly defined in terms of overall concept and song selection; they were all themed, to be considered as discrete units separate and distinct from the conventional business of 78 rpm singles. Lovers was very consciously designed by Sinatra and Riddle to be the polar opposite from its predecessor, 1955's In The Wee Small Hours - this album was to be about happiness, since it would have been hard to match the intensity of laments like "It Never Entered My Mind" or "This Love Of Mine."

Even more importantly, it was intended to sound modern, and it's a tribute to producer Voyle Gilmore in the Capitol Tower as much as Sinatra and Riddle that Lovers has not dated an iota in the 52 years since its original release. There is in its grooves nothing of the pre-war dance band quavers or apologetic politesse which still ruled much of British pre-rock pop; Lovers sounds hip, aware and possibly a good deal more so now than some of the music intended to supersede it.

Riddle's triumph lies in the fact that his arrangements and orchestra speak to and with Sinatra, answer him back, such that there is the feeling of an ongoing conversation - barroom or otherwise - seldom found in pop at the time. The opening "You Make Me Feel So Young" very properly sounds like a shiny, yellow herald of a new and better world; Harry "Sweets" Edison acts as Sinatra's unspoken conscience almost throughout, adding his muted trumpet comments to nearly every track, but look also at Riddle's subtle use of flutes, for instance; on "So Young" they flutter like autumn leaves in response to Sinatra's "old and grey" and at other times talk in the manner of the woman who is making him so happy. There is a beautiful inevitability about Riddle's build-up, especially when the cathartic bells materialise at the request of Sinatra's "bells to be rung" to say, away with the war, with the old, with paying back, with saying sorry; now and tomorrow are what count, the new marriage made in post-war heaven, a beauty so cherishable that you can easily excuse and understand Sinatra singing "you make me feel so spring has sprung" in the second verse.

Yet Lovers is not unambiguously happy. True, songs of lost or missed love, such as "It Happened In Monterey," remain buoyant in arrangement and delivery ("Monterey" even sees Sinatra doing a Slim Gaillard-style slide from "hip" to "low") as though to shrug their shoulders and say, well, these are the breaks, and wasn't I a dork (see also "Swingin' Down The Lane" with its boisterous trombone riff subsequently borrowed by Matt Monro for "My Kind Of Girl" - and note the unhackneyed and never predictable selection of songs throughout). Even a melancholy song like "I Thought About You" with its moonlit views of little towns, 2-3 cars parked under the stars, depicts the temporary sadness of the husband who has to go away on business, or on tour, rather than permanent loss.

The latter is barred from the album, but its emotional centrepiece, "We'll Be Together Again," cannot be overlooked since it's the axis of experience around which the happiness of the rest of the record revolves. With lyrics written by that reassuring bear of a beacon of fifties pop, Frankie Laine, this song comes nearest to the rueful deserts depicted in Wee Small Hours; again, both song and singer make it abundantly clear that this separation might be long-term but ultimately only temporary - the Glenn Miller-style tenor and baritone sax unisons may suggest a remnant of wartime memories, and Riddle's rather brash brass-dominant fills seem very anxious to reassure the listener that this is not In The Wee Small Hours territory) - and yet the terror which momentarily flits across the first of Sinatra's "Don't let the blues make you bad" is the key to Lovers' ecstasy. From this song alone we know that the joy of "Skin" or "Young" has been hard won, battled for, and so it gives the album's theme of happiness the vital perspective (note also how Sinatra worries the word "dreams" in "You Brought A New Kind Of Love To Me" as Riddle's orchestra seems to crouch down to hear him - and then glory in the liberation which comes when the song raises its blinds to welcome in the lushly yellow sunrise of the strings).

Elsewhere it's a case of exulting in Sinatra and Riddle's endless reservoirs of invention; the lovely and ingenious use of harp throughout, the mocking clarinet which quotes "Holiday For Strings" at the beginning of "Makin' Whoopee," the Johnny Hodges-like alto obbligato throughout "We'll Be Together Again," the running battle between ego and id in "Old Devil Moon" which finds Sinatra initially floating, out of tempo, over harp, muted trumpet and flutes, and never quite settling; his voice seems to fly free of Riddle's anchor but note the surprising if brief atonal brass figures responding to his "laugh like a loon" balanced out by the flying flutes behind "free as a dove" - yet this dove is clearly a perilous one since it is ultimately brought back down to earth by a lurking Elmer Fudd floor tom. The blossoming euphoria of "Too Marvelous For Words" - only Sinatra could make the word "dictionary" sound so liquidly sensual - is bolstered by its pair of brief bass solos (with foot stomping accompaniment) before Sinatra again stands (via two "to ever be"s) on top of the mountain, Tensing's last sly step onto the Everest summit.

And towards the end of the album there's even the birth of metapop; "Anything Goes" sounds so effortlessly hip that Sinatra is clearly happy for anything and everything to go, such that as he coasts over Riddle's triumphant trumpets at the end he adds, "May I say before this record spins to a close?" before diving back into the song's properly improper conclusion. The album as thing in itself, the happy advent of the new; Songs For Swingin' Lovers! continues to define the parameters, and its "Skin" is the key to the new, large kingdom set, if fortunate, to outlast the crumbling and tumbling Rockies and Gibraltar, if not quite the radio and the movies.