(#2: 11 August 1956, 2 weeks; 1 September 1956, 4 weeks)

Track listing: Introduction/Main Title: The Carousel Waltz/You're A Queer One, Julie Jordan/When I Marry Mr Snow/If I Loved You/June Is Bustin' Out All Over/June Is Bustin' Out All Over Ballet/Soliloquy/Blow High, Blow Low/When The Children Are Asleep/A Real Nice Clambake/Stonecutters Cut It On Stone/What's The Use Of Wond'rin'/You'll Never Walk Alone/Ballet/If I Loved You (Reprise)/You'll Never Walk Alone (Finale)/Carousel Waltz (LP Version)

Stage and film musicals play such an important part in this story that it is immensely regrettable that the compilation/Various Artists rule has edged most of them out for the best part of twenty years (but for those of you considering whether I should institute a compilation-only supplement to this blog the answer is a firm and decisive NO).

In particular the musicals of Rodgers and Hammerstein tower with some imposition over the Blackpool of the British album chart, and true to unpredictable form I find myself commencing their story with the difficult one, the toughie. Carousel was their second collaboration (and their second musical to be made into a film) after Oklahoma! but its soundtrack got to the top first. In most ways the soundtrack was more popular than the film; Carousel the movie was not a great commercial success, doesn't get screened much on terrestrial TV and even its stars seem to have had little to say in its favour. I last watched it a few Christmases ago and as a film it is dull and stolid, as befitting its bizarre choice of director Henry King, a Virginian old-timer whose films seemed to define dullness and stolidity whenever Gregory Peck wasn't involved (Twelve O'Clock High, The Gunfighter). Rodgers and Hammerstein themselves kept their distance, whereas they had been fully involved in the film of Oklahoma!

As a soundtrack, however, it is an intriguing and disturbing, if not quite coherent, artifice, something that a decade-older Brian Wilson might have cooked up. I should note here that my assessment is based on the fully remastered and expanded true stereo edition of the soundtrack released by Angel Records in 2001, featuring many songs and sequences absent from the original LP issue; 18 tracks over 70 or so minutes. While this is not quite the album which topped our charts at the time, it contains everything that was on that album and is undoubtedly what would have been released had the technology been available in 1956.

And it makes for a more disquieting story. Carousel is by some distance the darkest and most elusive of the pair's collaborations; it was based on a Hungarian play called Liliom written by Ferenc Molnar in the early twenties, and its writer held out on approaches from Puccini and Gershwin some years before Richard and Oscar came calling (or his agent persuaded him to go and see Oklahoma!). The Budapest-set original is even bleaker; the titular anti-hero, after falling on his own knife after a botched robbery, learns no lessons, and when allowed back down to Earth for a day to set his family aright, finds that there is no common ground and he is unable to change or improve anyone or anything.

By definition, then, Carousel was an unusually introspective musical for its time, full of missed chances, fumbled love declarations and the stupid, stolid inability of any of its characters to drag themselves out of their respective traps. It was, inevitably, bowdlerised to a modest extent for the film; Billy Bigelow is accidentally shot while fleeing the robbery scene rather than committing an ignoble suicide, and while in the stage version his unlikely progress to Heaven is told chronologically, the film uses it as a framing device; he ponders whether to return, during which meditation the story is told in flashback.

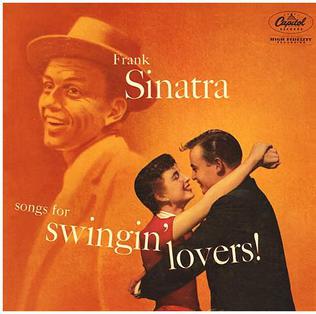

Furthermore, the film did not end up as was originally intended. Frank Sinatra was the original choice to play Billy - and Nelson Riddle was among the orchestral arrangers - and even pre-recorded his big numbers in preparation for filming, but when on the first day of shooting he was told that he would have to shoot every scene twice - once for the then new Cinemascope technology, and again for the normal 35 mm stock film - he demurred and disappeared. Gordon MacRae appeared in his stead, and so the Oklahoma! pairing of MacRae and Shirley Jones (as his wife Julie Jordan) was repeated, albeit less successfully.

In fact I think MacRae captures Billy's bluff ignorance far more convincingly than Sinatra would have done; he is called upon to harvest reserves of vulnerability which Sinatra would never have allowed himself to see, let alone us (at least not until Gordon Jenkins drew them out of him on their later collaborations) and his lunkhead operatics perfectly reflect the inarticulacy which proves Billy's Achilles' heel.

The soundtrack does not begin as you would expect a musical to begin; a whistle, dissonant hand bells, distant organ drones and a liberal use of whole tones conjure up a meeting between Pharaoh Sanders and Scott Walker, while Billy paints his stars in Heaven and meditates on the notion of coming back down, though his foolish, fatal stubbornness suggests that any lessons have sailed past his bay; so much so that he wonders what's wrong with his boy, when in fact he has fathered a daughter.

Then the main waltz theme comes in, sinister and mechanical, played by organ and orchestra as though suppressing a sob or a scream. Brass, harp and percussion seem to combine to smash fugitives down from an undeserved afterlife; the final, dreadful chord sounds like a stage curtain being ripped down rather than opened.

Thereafter the story is difficult to grasp from the sequence of music alone; instead we are given a near-abstract procession of monologues and conferences from the various characters involved, lots of orchestrated talk which ceaselessly returns to the theme of whether this tragedy is worth talking about at all. Carrie Pipperidge (Barbara Ruick) tries to understand why her best friend and workmate Julie Jordan isn't saying much, wonders what she's trying to hide or doesn't want her to know, and in an effort to persuade her to explain talks about the supposedly wonderful things about to happen in her own life. Where Julie merely says something dissolute about liking to watch the ocean meeting the sea, Carrie talks about her impending marriage to Enoch Snow. Sounding throughout like a substitute for Doris Day, Ruick's voice seems always on the brink of crying; there's an essence of forced gaiety about her stance. She's marrying Mr Snow but doesn't really sound too ecstatic about it, as witness her suppressed distaste for the after-effects of his trade as fisherman; she hisses on the "fish" of "smell of fish" and sneers the word "flat" in a way which doesn't appear to refer to the type of fish he catches. Making do and mending seems to be the moral here, and the Snows (of Kilimanjaro? - another King/Peck collaboration) are used as a vaguely ironic counterpart to the troubled course steered by Billy and Julie, even though there's not much evidence to suggest they're going to be any happier; Ruick's "I'll be as meek as a lamb" seems an explicit parody of Doris; her "darling" is exaggeratingly sweet to the point of bitter.

Then, without warning, we cut to Jones and MacRae for their great setpiece "If I Loved You," perhaps the bleakest "love duet" ever seen in a Hollywood musical; they take turns to describe their paralysing reticence to commit (they are Jane Eyre and Rochester rendered inert by the stifling trade winds of late nineteenth century Maine, though it's worth bearing in mind that these events are contemporaneous in time with what was happening in Hardy's Wessex, and the President of the Immortals is never far away from the events in Carousel). Since on the soundtrack there has been no introductory meeting, and the film merely makes it clear that Julie fancies a bit of rough and ends up roughshod, we have two separate spirits here, completely unable to communicate what might or might not be love to each other; their "longing"s represent a fortissimo surge and their "afraid"s a pianissimo retreat. The song never goes over the edge and its ideations are a direct precursor to "I'm Not In Love." Billy's "afraid to be caught stealing the night" is deliberately prophetic and he breaks off midsong to consider the futility of saying anything: "What are we? Just a couple a' sparks a' nuthin'" (and the film version suffers here, since the pained "There's a hell of a lot of stars" with the accent firmly on "hell" is changed to "Why y'can't even count the stars..." Billy, as stubbornly and unjustifiably proud as ever, can only entertain the notion of changing himself with extreme difficulty; he sees himself married, "kind of scrawny and pale, pickin' at my dinner.../Dress like a dude in a dicky and a collar and a tie" with all the contempt reserved for the impotent "dicky." Again and again the song's waves surge, again and again they stop before breaking and flooding over - this is "This Guy's In Love With You" prematurely stripped of all hope.

"June Is Bustin' Out All Over" is introduced by a rather threatening chordality of strings - in the foreknowledge that winter will come again - intruded upon rather suddenly by slightly over-eager brass and voices. Ruick's midsong pause of "Fresh and alive and gay and young/June is a love song sweetly sung" is made to sound like an elegy for the tomb before the routine starts up again. For - as the extended ballet sequence demonstrates - the celebration is one of sexuality, its metaphors drawing in everything from sheep to ships, even though it doesn't quite get away from the idea that there is something to fear about sex; remember that Julie loses her job at the factory as a result of staying out late with Billy and missing her curfew - even though she is supposed to be in her twenties. But the urge to fuck is undoubtedly present; "You can feel it COME" over quickening beats and subsequent three-stage orgasm of "TURN AROUND!"

But then it's back to MacRae's solo feature, "Soliloquy"; having failed to persuade or touch Julie, he is finding it difficult to invent his own future. A crepuscular string motif predicates Scott Walker again (and indeed recurs on "Rosemary," from Scott 3) as Bigelow makes his dense effort to understand men and women and the universe as intently and misleadingly as Major Amberson before the glowing fire. Indeed this extended fantasia underlines one of Carousel's main themes; the alleged gulf between women (as life-giving form and symbol of endurance) and men (who get distracted by and drowned in their own dreams). Billy convinces himself so surely of the unshakeable virtues of the non-existent Bill - with the emphasis on "His mother...won't make a sissy out of him/not him/not my boy/not Bill!," each "not" expressed with mounting pain, his disinterest in whether he ends up a glue seller or President ("his mother would like that") and his fierce, piercing and terrifying yells against would-be bullies and bosses betraying his own dread of settling down and knuckling under, although his fiercest contempt is missed in the film, since the boss' daughter, unforgettably described on stage as a "skinny lipped virgin," becomes a "skinny lipped lady," though MacRae does his best to lick every iota of cream off that "lady" - that when he considers the possibility of a girl (while dwelling on how Bill will get along with, or more to the point get round, a girl) he is genuinely shocked: "Aw, Bill...Bill!" He ascribes the gender difference as being that between having fun and being a father, relishing the prospect of her coming home to him rather than one of her 2-3 boyfriends a little too avidly, before roaring that she will not be dragged up in a slum "with a lot of bums like me." His battle between ego and self-deprecation atomises, and he signs his death warrant: "I never knew how to get money but I'll try, I'll try, I'll try (in the original he sings "BY GOD" thrice).../I'll go out and make it or steal it or take it.../Or DIE!!"

After that we cut to his no-good buddy Jigger Craigin, played by Cameron Mitchell in an lustily enterprising amateur singer kind of way, and he doesn't give a blast; he's also looking out to sea but what he sees is a different picture from Julie's, with the boat as metaphor for both woman and baby's wet behind. Then it's back to the Snows with "When The Children Are Asleep," substantially simplified from its stage version but the traps are already and predictably in place; Enoch (Robert Rounseville) reveals himself to be a tedious and arrogant bore, more concerned with business than his marriage, as he visualises his boats, his children (never mind her) and even "our dear little house" all expanding, getting bigger (to which Ruick sardonically responds, "and so will my figure"). They move on to consider the kind of dreams they'll dream together at night (i.e. fucking) but there's something of the future pot-bellied, baggy-eyed bully about his sternly deflating "Dreams that won't be interrupted" and Ruick's "if I still love you" can easily be read as a veiled threat.

This world seems scarcely worth living in. "A Real Nice Clambake" attempts fireside cosiness with its accordion and slowly amplifying chorus but Mitchell splits it open in the middle with his "Then at last come the clams" which not only sounds like a death march but also like a forebear of Don Preston's Lion in Escalator Over The Hill, that magnificent ode to the art of anti-singing. The song doesn't quite recover from that intrusion, and it is during the clambake that Craigin and Bigelow break away to carry out the robbery.

Two more extended gender debates follow: "Stonecutters Cut It On Stone" views the futility of commitment or indeed love from both perspectives; for Jiggin it's a needless handicap to fun, fun, eternal fun, while the female chorus set up a surprisingly aggressive proto-feminist counterattack; "It's cook and it's scrub and it's sewin' all day and not much sleepin' at night (altered from the original "and God knows what in at night")." The conclusion is that "there's nothing so bad for a woman as a man who thinks he's good" (see "Soliloquy") except that the girls reckon bad OR good is equally destructive.

Julie, who has held her tongue for half an hour or so, then reappears, sadly asking, "What's the use of wondering if he's good or if he's bad?" Darker even than "Stand By Your Man," "What's The Use Of Wond'r'n?" sees unquestioning fealty as merely a slower march to the gallows, a pointless mothering (she sings of giving kisses "to the lad") and the song finally drives in on itself and sinks - "and all the rest is talk," "there's nothing more to say" - as a bell tolls and the Greek chorus see the unhappy ending on the horizon.

There has been nothing in the way of romance in this story as the soundtrack has perceived it, little even of sex or freedom as anything more than pallid signifiers. And into this graveyard comes that song. It is easy to see how audiences in 1945 would have been stopped in their tracks by its bleeding balm of comfort, and here it appears twice; in the first version, Jones seems to be attempting to sing it down a telephone line but she can't do it, her tears prevent her from singing the word "dark" as though such concepts were foreign to good old neighbourly Booth Bay Harbor, so Cousin Nettie (Claramae Thomas) takes the song over and gives it a sprinkling of nobility; the song whose subsequent life could hardly have been envisaged by its composers, a song which Gerry Marsden took to number one twice, in two different generations, two different Britains; one where everyone had everything to live for, and the second (and to me the more affecting) when everything seemed to have been lost (and what happened in Bradford and Heysel were merely manifestations of Thatcherism taken to their logical and bloody conclusion).

Then the ballet sequence, nearly ten minutes long and also serving as overture and precis, which steadily subverts and eats itself; it begins as a jaunty and nautical hornpipe but eventually gives way to tombstone trombones, strings and xylophones, all brought to a sudden stop by the Godlike gavel of the timpani, putting the reverie to an abrupt end and replacing it with nightmare; the return of the Carousel Waltz, played as though at a funeral (see also the use of the calliope on Escalator). Once again, brass and percussion take over, woodblocks and tambourines being wielded like sabres.

The motif from "Soliloquy" now returns, played by a mournful viola (cf. Nancy Newton's introduction to the song "Escalator Over The Hill"); this gives way to a curiously Vaughan Williams-esque pastoral interlude for briefly flourishing strings and French horn which in turn leads to a reprise of the "If I Loved You" theme, fortissimo and as heartbreaking as the major key into which Bernard Herrmann moves his music as the sledge burns in Kane, topped by a dreamy whirlwind of woodwind (see also "Soul Of A Woman," the exacting coda to the Four Seasons' Genuine Imitation Life Gazette: "then you give yourself to him forever"). Following a brief return to the "Soliloquy" theme there is an abrupt intrusion by sneering schoolchildren, yelling "Shame on you!" over and over and then "SHAME! SHAME! SHAME!" over quickening and now threatening beats (at Louise, the daughter of a failed robber) until the music explodes and Louise screams "I HATE YOU! I HATE ALL OF YOU!" and the sequence is brought to an end with a terrifying Bartok-dissonant anti-fanfare of trombones, tympani and thunderclaps which might be closing the world down.

There is nothing now but for the ghosts to take their final bow; first Billy, who does effect positive change in the film but you wouldn't know it from here, reprising "If I Loved You" as "now I've lost you" - and I can't see how Sinatra would have been willing to risk that final falsetto "how I loved you" which more or less creates a template for the works of Roy Orbison. And then, perhaps most terrifyingly of all, Shirley Jones, with discreet chorus, singing the song of reassurance in the full knowledge that not everyone can be saved if they don't care about salvation, and even here the nightmare isn't absent; the threatening brass is present here too, and the final, emphatic thud of the timpani sounds like the last nail of the coffin being hammered in. It's a long way away from the "you are not alone" tenderness expressed by the ghost of The Baker's Wife at the end of Sondheim's Into The Woods, another cautionary tale about people who believe in dreams at the expense of reality, and in some ways is a cautious reversal of the final scenes of Mizoguchi's Ugetsu Monogatari (though since that latter film was made in 1953, I wonder how much it in turn was influenced by Carousel, or for that matter Liliom).

Not that anyone else will necessarily die; the bitonal/atonal "Carousel Waltz" continues to wend its unquiet way as we make our exit, in the hope that we might have cleared the cinema by the time it unleashes its terrible, multiple stabs of chords right at the end. The Snows will continue because they don't know how not to; they will thrive, have children, go conservative and stale. Shirley Jones, in contrast, will endure, as the mother of a fatherless family which will include, in David Cassidy, the last thing Billy Bigelow wanted Bill Jnr. to be. Or possibly the first.