(#53: 9 March 1968, 10 weeks; 25 May 1968, 3 weeks)

Track listing: John Wesley Harding/As I Went Out One Morning/I Dreamed I Saw St Augustine/All Along The Watchtower/The Ballad Of Frankie Lee And Judas Priest/Drifter’s Escape/Dear Landlord/I Am A Lonesome Hobo/I Pity The Poor Immigrant/The Wicked Messenger/Down Along The Cove/I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight

“An avidity to punish is always dangerous to liberty. It leads men to stretch, to misinterpret, and to misapply even the best of laws. He that would make his own liberty secure must guard even his enemy from oppression; for if he violates this duty he establishes a precedent that will reach to himself.”

(Thomas Paine, Dissertations on First Principles of Government, 1795)

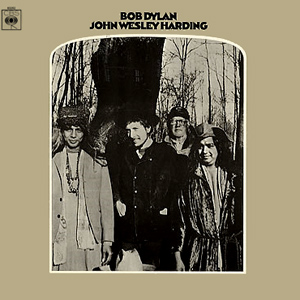

Although most think of it as a 1968 album, John Wesley Harding appeared in the record racks on 27 December 1967. There were many who could have justifiably laid that year to rest by having the last word on it but Dylan’s was the most avidly awaited and the least noticed or expected. The album sneaked out less than a month after the recording sessions had ended; Dylan was keen on there being no hype, for the work simply to materialise.

There were, as I said, a few other “last words” appended to 1967; Wild Honey saw the Beach Boys getting back to basics in a far more pragmatic way (because driven by necessity). Love’s Forever Changes sees its world dying and only gradually clears its mind as to what kind of new world it wants to replace it. Meanwhile, the Velvet Underground’s White Light/White Heat was as violent a repudiation of what 1967 stood for, or was supposed to stand for, as anything released by Engelbert Humperdinck; throughout “Sister Ray,” Reed and Cale meticulously pull apart every last atom of bubblegum to reveal an awful new dawn.

John Wesley Harding, however, became recognised,, and was prominent in a year from which its creator was otherwise largely absent. Note that the record stayed on top in the UK for some three months – interrupted for one week only by entry #54 - and that this run covered the period of the Paris riots, the King and Kennedy assassinations, the worsening of the Vietnam situation, the gradual return of Nixon. Clearly, 1968 was turning out to be the gruesome antithesis to everything 1967 had promised, and it was therefore the case that this album was needed – it spoke to a community which painfully needed to be reassured. True, May 1968 also saw the gleeful autodestructing fusillades of Mantler’s Communications – three of its five pieces were taped that month - and Brötzmann’s Machine Gun, but security was needed in tandem with revolutionary urges.

In particular, John Wesley Harding recognises that revolution has no point or purpose if, in its ashes, we cannot recognise and acknowledge our friends and neighbours. Sgt Pepper was all about community, but the stage remained raised. In contrast, Dylan spent most of 1967 laid low in Woodstock, with the band who would eventually become The Band, hanging out, making music and writing songs for its and their own sakes; he also became a father that year, and this all combined to a clarification – if not a simplification – of his aesthetic world view.

It is virtually impossible to speak of the album without reference to the (predominantly) Canadian group who, by finding and forming their own true identity, helped to identify a way out; not quite a third way, but the way 1967 had always intended. Music From Big Pink only peaked at #30 in the States and didn’t chart at all in Britain; nonetheless, its example subtly permeated most of the worthwhile music which would emerge from the remainder of its decade. With the partial exception of Levon Helm, the Band had accompanied Dylan through his most turbulent and ecstatic music and indeed had enabled it; the surge of excitable, righteous noise which constitutes the electric half of the 1966 “Albert Hall” concert retains a power second to few, if any, of its peers or successors. But one can only scream for so long before becoming hoarse, and before long both Dylan and the Band were looking for something else – namely, who and what they really were, what it meant to be “together” in 1967, how that could be perpetrated and extended into a meaningful future. Throughout The Basement Tapes the fun in music-making seems much more high than chill, since the intent was to help create, or at any rate suggest, a new notion of society. It’s arguable that John Wesley Harding was the most literal, and also the most serious – because, finally, it was the most lighthearted – interpretation of the Pepper message. The screams of post-Highway 61/Blonde On Blonde surrealism could only end up entangling themselves in their own constructs, as Lennon smartly demonstrated towards the end of 1967 on “I Am The Walrus,” the nearest aural equivalent of an artist’s brain exploding. You’ve turned the tables over, now what food do you propose to serve from them?

Music From Big Pink demonstrated, just as John Wesley Harding does, how much the Band and Dylan had learned from the Woodstock sessions; “Tears Of Rage” remains the most startling (because so unexpected – a ballad?) beginning to any 1968 “rock” album, and despite the appearances of 19th century revivalism, side two (from “We Can Talk” onwards) is as musically radical (but not in a spell-it-out, exhibitionist sense) as anything released in that year. It is the sound of a decade-old group getting inside itself and, by doing so, exceeding its own expectations, as well as inventing, not so much a new language, but a new perspective on the old language. Adult music without the oppression of adulthood to weigh its boots down, but by no means divorced from pop (Robbie Robertson knew his Curtis Mayfield licks all right in 1968).

Likewise, some still speak of the Dylan of John Wesley Harding as a savage repudiator of his own recent pop past, and even now people are saying similar things about Manafon, David Sylvian’s new album, with its opening gambit of a placid wrecking ball smashing down the false idols of a quarter-century’s misplaced trust. But I’m not so sure that either record – each about different perspectives of an individual as projections of the artists themselves, be it a 19th century American outlaw or the 20th century Welsh radical poet RS Thomas (who, as Sylvian notes with a smiling sadness on the album’s titular closing track, could be so purist that he ended up “not knowing his left foot from his right”) – could exist without a keen awareness and underlying love of pop. Both Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde On Blonde – both top five albums, but not number ones, in the UK – had erected a wall of nowness which was unbreachable and vital. But although Dylan pared his poetic language down – relatively - for John Wesley Harding and simplified the music (in terms of participants and arrangements, if not activity or inventiveness) considerably, the dozen songs here are hardly less radical than those of their two predecessors. If you choose to judge the record by its bare-boned bass/drums accompaniment and its procession of simple, parable homilies alone then it will seem less obviously radical than 61 or Blonde. The way Dylan sings and plays these songs, however, the spaces between his thoughts, between expression and fulfilment – these suggest that the adventure had simply been channelled into subtler waters.

The album was recorded over three sessions in Nashville with stalwarts Kenny Buttrey on drums and Charlie McCoy on bass – Dylan briefly considered calling in Robbie Robertson and Garth Hudson for some overdubs but both parties agreed that the songs were fine enough as they stood – and the opening title track, like so many of these albums under consideration, provides the key for the rest of the record; here is a straightforward song about a less than straightforward man who formed his own Robin Hood path to righteous redistribution. He never gets caught or nailed down, he helps those who deserve to be helped, and in particular he serves whatever community he finds himself inhabiting, even bringing multiple communities together by his peculiar example (“All along the telegraph/His name it did resound”). Johnny Cash would have recognised the air in an instant, and Buttrey and McCoy tick unobtrusively behind Dylan’s voice, guitar and harmonica until, alerted by a change in intensity in the vocals (on the line “To lend a helping hand”) and the electrifying intrusion of Dylan’s harmonica, Buttrey’s drums suddenly stir and become busy (and yet again provide an unlikely precedent for drum n’ bass); they too are breaking their bonds. This is the landscape against which Dylan’s dramas are played out, the land through which he himself – if he fancies himself as Harding – is travelling and from which he is reporting back his findings.

So he wanders out one morning, this worried man, sees a statue of Thomas Paine somewhere and gets to thinking, to the tune of a medieval lay; all of a sudden this girl in chains runs up to him, asking for unity, pleading to fly South – to the land of the oppressors? But the marbled example of Paine, rather than the true memory or material of the man himself, refutes her on his behalf, tears her away with the fateful avidity to punish that scars his would-be disciples. Dylan’s hurt arc of “as she was letting GO-O-O” speaks tears of its own forfeited heaven.

Comfort is very far away at this point. The worried man – where are those directions home? – has visions of the victimised monk, who growls “Go your way accordingly, and know you’re not alone” (we’ll get back to that “you’re not alone” much later on in this tale), and then imagines himself as one of his killers. Dylan’s concluding, devastated “and bowed my head and cried” was as excoriating a cry as any to be heard from the more easily excitable quarters of 1968.

“There must be some kind of way out of here,” he then tries to reassure us, to a fast, sprightly but disturbed beat which puts me in mind of the Four Tops, as he summons up and surveys the impending apocalypse. “Life is but a joke,” he sings, unconsciously (or not) echoing the Supremes’ “Is this game of life a mistake?” As his wind begins to howl – and his wildcat as terrifying a dead end as any black dog Johnson or Drake might have encountered – his harmonica honks and howls aridly, like a dessicated Pharaoh Sanders. Hendrix only needed to increase the tempo slightly, change the rhythmic accents, volumise his grief and impose three crucial worlds of mourning guitars upon its jigsaw to switch the lights on for an electrified world’s end – and, as Dylan and the Band would play it a few years and several lifetimes later on the Before The Flood collection, “Watchtower” can still come across as the last song issuing from a burned Earth.

This apocalypse, however, is recognisably the same one through which the narrator of “A Hard Rain” once travelled, and we know that he has simply continued his travels through the fire and the flood; John Wesley Harding could be interpreted as his most fulsome bulletin. “Frankie Lee And Judas Priest” bounds along joyfully on its trampolining rap for nearly six minutes – “With a soulful, bounding LEAP!” – with its fairly simple analogies; don’t mistake paradise for eternity, let alone the other man’s grass, but at the same time don’t imagine that you can get through this hellish world alone in order to make it heavenly. But Dylan makes the choices as icy and unavoidable as those offered to the hapless knight in Walker’s “The Seventh Seal,” and again his harmonica – John Wesley Harding offers much of Dylan’s bluntest and most passionate harmonica playing – seems to shred souls to the dimensions of shrunken early spring morning icicles. Side one concludes with Dylan’s most tortured vocal on the record: “Drifter’s Escape” sees his unwilling accused in near-indescribable worry (“Oh, help me in my weakness!” he numbly screams in a vacant lot of a falsetto at the song’s beginning) before his court is destroyed by a lightning bolt and, while everyone else kneels down to pray, he flees (knowing that this is “ten times worse” than any “trial”). Note how McCoy’s bass mimics the judge’s gavel at key points in the song and how, as the drifter (or Number 6, since the scenario is strikingly similar to that of “Fall Out”) escapes, so does his bass begin to roam free and breathe.

While the country influences on John Wesley Harding have long since been accentuated, the deep soul input is rarely summoned to anyone’s attention; “Dear Landlord,” however, has an arrangement which could have come straight out of Otis Redding, its considered piano duelling with McCoy’s emphatic, repeated high A bass notes (particularly noticeable on the phrase “beyond control”). The operatic midtempo setting also suggests the barren walls of James Carr, although Dylan’s pleas for understanding and tolerance to his mother nation are more in keeping, vocally, with John Lennon.

But what if the nation rejects its son anyway? On “Dear Landlord” the worried man begs for entry and acceptance, but on “I Am A Lonesome Hobo” he’s still trying to find his roots; he’s tried everything (bad) and gotten nowhere (fast) – as with all the other misguided perpetrators we meet on this record (if they are not all reflections of the narrator himself), he has found no joy or permanence in material things, but still knows enough to warn the rest of us not to end up like him, not to be crucified by “petty jealousies.” As though to ram the point home, his atonal harmonica crackles into the picture like fugitive Mary Chain feedback.

On “I Pity The Poor Immigrant,” however, the harmonica takes on the solemn, stately confidence of a church organ as Dylan demonstrates Paine-like compassion for the outsider who comes in to wreck the world – an allusion to Vietnam? As with “A Day In The Life,” he’s artful enough not to need to spell it out – but who ultimately only ends up destroying himself, the man who mistook Paradise for the nation across the sea, who can make nothing save foolish moves. Again there is the emphasis on rejecting the material – “Who falls in love with wealth himself/And turns his back on me” – and the nothingness to which this abject worship will, in anyone’s end, lead him. Pity for the enemy? Was this allowed in the 1968 of beaches underlying pavements? Dylan’s narrator has less time for serial complainants; “The Wicked Messenger” is only wicked by (anti-)virtue of his ceaseless, self-directed whining, and by the time his exhausted audience inform him, “If ye cannot bring good news, then don’t bring any,” he unaccountably finds that these words have “opened up his heart” – and so the album, finally, opens up to admit humanity and love.

And Pete Drake. The first noticeable thing about “Down Along The Cove” – other than how much it resembles a mid-period Elvis movie theme tune – is a fourth voice we haven’t heard before, that of a pedal steel, and since the song’s theme is summed up by the refrain “I spied my true love comin’ my way,” the precise antithesis to the stony rejection of “As I Walked Out One Morning,” it is apt that this new voice should speak in tones feminine. Here the man begins not to be worried, and finally discovers the life he surely knew was his for having all along, realises the joy in settling, in neighbourliness and companionship as well as love. “Ev’rybody watchin’ us go by,” exclaims Dylan, “knows we’re in love – YES – and they understand.” And all of a sudden the Edmund Spenser language and the multiple Old Testament references retreat into the background; this is life, this is nowness, this is how 1967 really intended and desired humanity to be.

Drake is there, too, for the home on the range, sunset on the prairie, finale, “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight,” skiing tracks of elision carefully (but caressingly) under Dylan’s Hank Williams (or Slim Whitman?) semi-yodel (in the phrase “mocking bird”). The wanderer recognises his heart as happy – “bring that bottle over here” – and his world never warmer, but with the glow of heaven rather than the fires of hell. The happy ending “A Day In The Life” deserved, and 1968’s deserved - and most necessary - chart champion, which established a precedent which reached far beyond its begetter.