(#358: 28 November 1987, 1 week)

Track listing: Never

Gonna Give You Up/Whenever You Need Somebody/Together Forever/It Would Take A

Strong Strong Man/The Love Has Gone/Don’t Say Goodbye/Slipping Away/No More

Looking For Love/You Move Me/When I Fall In Love

I hardly ever listen to Pick

Of The Pops these days as, unlike what would seem to be the vast majority

of Radio 2 listeners, I am able to lead a contented and fulfilling life without

the need to hear “Maggie May” or “Love Train” ten times per day. I understand

completely why the programme should trounce Radio 1’s The Official Chart show so soundly in the ratings, though note that

it itself is trounced by almost the same margin by Capital Radio’s Vodafone Big Top 40 programme, which

does not halt the flow of music or enthusiasm by calling everything “Official”

and assuming that its listeners do not possess a level of intelligence

equivalent to a two-year-old child or a capacity for memory retention similar

to that of a goldfish and do not need to have the same few phrases shouted at

them every twenty seconds.

Then again, you might think that in a world which is

speedily going to hell, or at least back to the fourteenth century, in a

handcart, people need the reassuring blanket of aged security that old records

and old charts offer. I don’t believe that the old is better than the new by

virtue of age alone, however, and this was quietly demonstrated by the first

hour of last Saturday’s show, which featured the twenty best-selling singles

from 1956. The fifties are a decade seldom revisited by the show – every few

months, as, I suspect, a tentative experiment in audience engagement – and

1956, with one foot still in the pre-rock era, is a territory practically never

ventured into. I noted with slight disappointment that the show wasn’t going to

go through the Top 20 of the week ending 7 January 1956, where, I think, hits

like Dickie Valentine’s “Old Pianna Rag,” two versions of “Suddenly There’s A

Valley,” Jimmy Shand’s “Bluebell Polka” and Winifred Atwell’s “Let’s Have A

Ding-Dong” would have befuddled too many people (despite there being, at number

one, something called “Rock Around The Clock” and something else called “Rock Island

Line” at number seventeen).

Still, the 1956 hour was a revelation, if only of how

shockingly dated, to the extent of being practically prehistoric, most of the

twenty featured records were. I well remember listening to a similar

retrospective chart show on Radio 1 at Sunday lunchtimes in the seventies – a programme

now written out of history due to its having being hosted by a broadcaster to

whom Anthony Burgess, correctly as it turned out, referred as “the most evil

man in Britain” – when these records were only twenty or less years in the past

(i.e. the distance between “Some Might Say” and now) and they already sounded a

bit pickled, a little frayed at the edges. But grotesque things like Anne

Shelton’s “Lay Down Your Arms” sounded eviscerated from the nineteenth century

(“March at the double down Lover’s Lane,” post-rationing self-denial in the age

of Rachman and Christie). Frankie Laine’s “A Woman In Love” simply sounded

ludicrous (“CRAAAAYYY-ZILLY GAAAAZE!”). Novelty instrumentals like “Zambesi”

and “Poor People Of Paris” bore a creak worthy of Edison cylinders. Rock ‘n’

roll-inspired novelties like “Rock ‘N’ Roll Waltz” hit bigger in Britain than “Be-Bop-A-Lula.”

Even forward-thinking records like Lonnie Donegan’s “Lost John” sounded decidedly

wrinkled, regardless of how many rock stars he or it may have inspired at the

time. Things like “It’s Almost Tomorrow” – though anticipating the quiet dread

of Fleetwood Mac’s “You & I Part II” – made me surprised that there wasn’t

a lute or a crumhorn to accompany the medieval plainsong. The year-end top

twenty contained two Elvis songs, but also two songs by Teresa Brewer, both of

which have dated quite atrociously (one, “A Sweet Old-Fashioned Girl,” tries

for Betty Hutton OTT-ness, but Brewer is too sweet to be convincingly unhinged;

the other was “A Tear Fell,” about which you can read here).

The music demonstrated how, and why, Presley became so big –

“Heartbreak Hotel” and “Hound Dog” in this context sounded as though they were

proclaiming against what surrounded

it – and otherwise, perhaps only Dean Martin’s “Memories Are Made Of This,”

Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers’ “Why Do Fools Fall In Love?” (Britain’s first

R&B number one) and, at a stretch, Doris Day’s “Whatever Will Be, Will Be,”

would still pass muster and remain playable now.

The reaction on social media thereafter was quite revealing;

many listeners had felt that the show had reached back a little too far, beyond their collective memory –

well, we are talking about music that is almost sixty years old – and most

seemed relieved to be immersed in the relatively familiar past of 1980 which

followed in the second hour (then again, 1980 alone is now thirty-five years

away, the same distance it was at the time from the end of the Second World

War). 1956’s charts were also a field for subtle, or not so subtle, separatism.

The “Only You” which hit big in that year’s Britain was not the Platters’

original, but the anaemic cover by white Kentucky college boys the Hilltoppers.

Top for the year – which added to the general sense of

anti-climax; was this as good as it

got? – was the record which kept “Heartbreak Hotel” at number two, Pat Boone’s

weepie “I’ll Be Home.” But this was a bastardisation of a 1955 record by the

Flamingos, whose original is superior to Boone’s in every way (the lyrics of Boone’s

version seems to transpose some of the Flamingos’ lines); Sollie McElroy’s lead

vocal is pained, ecstatic and dread-filled all at the same time; Boone does not

attempt to repeat the “A-a-a-a-at the corner drugstore” which opens the second

verse, and being a black doowop group from Chicago, their intonation of lines

like “Our love will be free” and even “I’ll be home to start serving you” – the

song is about a serviceman called off to fight – necessarily carries a deeper

weight than Boone’s, which imply that to “be free” is to be free of dirty

Commies. On the B-side was his blasphemous downsizing of “Tutti Frutti.” This

is the world into which John Lydon was born.

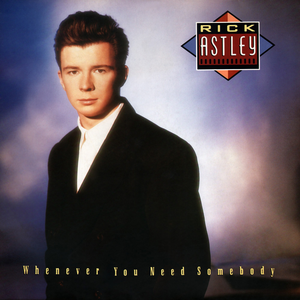

You may wonder what any of this has to do with Rick Astley.

But to look at his apprehensive apprentice face on the cover of Whenever You Need Somebody, you could

have been forgiven for thinking that the intervening three decades had not

happened. Actually, Astley was a tougher character than that; when discovered

by Stock, Aitken and Waterman he was singing (having previously drummed) in a soul

band called FBI, and four of the album’s ten songs were written or co-written

by him. Nonetheless, the record’s deliberately arcane liner note, telling the

lad’s story as though it were still 1957 and he were a Tommy Steele of the

North, sets out a gradual but steady and grafting rise to fame; Astley was one

of the first musical beneficiaries of the Enterprise Allowance Scheme, one of

the Thatcher government’s few good ideas (£40 a week – in eighties money – to start

up and run your own business; and it should be reinstated, taking inflation

etc. into account; £40 a week doesn’t sound much now, but in the mid-eighties

it went a very long way) and he was then employed in SAW’s studio in

Bermondsey, learning the business from tea-making upwards. A classic tale of

free enterprise, in other words.

Now, I have to be clear here; I am an ardent fan of the work

of Stock, Aitken and Waterman. I refuse to join in the sneering demolition job

that is still being carried out on their achievements by commentators who

really ought to know better. Along with New Order, the Pet Shop Boys and the

Smiths, they basically kept the British pop single going in the puzzling days

of the mid-eighties (and slightly less puzzling ones of the later eighties) and

their commercial and aesthetic pummelling of the majors by, essentially, punk

rock means is a New Pop feat in itself. “Today’s Sounds/Tomorrow’s Technology!”?

I’m all for it.

But SAW were at their best as a singles team. With albums

they tended to struggle, and once you get past the frontloading of hits there

tends not to be too much else of interest. Moreover, they worked best with acts

who had a bit of fight about them, who argued back and who, overwhelmingly,

were female. Mel and Kim, Bananarama, even Mandy Smith (whose “I Just Can’t

Wait,” the “Cool and Breezy Jazz” 12” mix thereof, also from 1987, is probably

SAW’s finest single achievement) and, God bless her Scouse boots, Sonia – not

to mention the Australian coming just around the corner (and there were more – Princess?

Lonnie Gordon?) – all gave back more, arguably, than was put in.

Whereas Astley sounds a little overwhelmed. The opening trio

of hits is fine enough; ideal soundtracks for strolling through sparkling,

glittery late eighties shopping malls, knowing bubblesoulgum for the M25 and

Big Bang, although one notices that a large part of Astley’s appeal was that he

was straight as a die. In a year whose serenaders included confusing,

ambivalent, troubled William Boldwoods and extravagant, flamboyant Sergeant

Troys promising the world, the girls settled for eighties pop’s Gabriel Oak.

Nothing wrong with this, per se;

Astley stands in the midst of a long line of reliable Britpop boys-next-door

which extends from Craig Douglas to Olly Murs – and is noticeably “meatier” of

voice than either.

Astley was loved for his sense of reassuring permanence, a

sense comparatively rare in the parallel world of rock ‘n’ roll. Listening

through the hits, I am struck at the sentiments they express. “A full

commitment’s what I’m thinking of.” “You wouldn’t get this from any other guy.”

Lyrics of the calibre of “I’ll always do what’s best for you” had been by and

large absent from mainstream pop since the days of Dickie Valentine, another

youthful reliable with a pleasant, if somewhat limited, vocal mid-range and an

approachable personality (although Lena wondered whether the 21-year-old Astley

didn’t more resemble “Frankie Howerd’s nephew”; that same “ooh, not ME, surely!”

quality). I also note that the title track was originally recorded, by SAW,

with a female singer called O’Chi Brown, with no commercial success, in 1985;

in a song which successfully manages to paraphrase both Dusty Springfield and

Steve Arrington, Astley sounds, if anything, like a stronger Mark King.

“It Would Take A Strong Strong Man” was not a single in

Britain, but went top ten in the States (as did the album) and topped the

charts in Canada. Noticeably more strident and pained than the more familiar

hits – you can picture Ashley, hoarsely yelling at the microphone – it suggests

that his adoration might in part be one-sided, an impression which the

faster-paced “Don’t Say Goodbye,” the record’s only remaining SAW-penned song,

reinforces.

The trouble is we then dive headlong into Astley’s own songs

– just to remove any tired notion that he was an SAW “puppet” – and they are…decent,

but not much more than that, and certainly not very memorable, not even the

Deep House anticipations of “You Move Me” which intertwines expressions of love

with humdrum life in Thatcher’s Britain – he works his socks off, but the boss

still calls him in to say, with regret, “Here are your cards” (is this the only

song with such a phrase in its lyric?). This side of Astley is better than

Curiosity Killed The Cat, certainly, but how low is that bar set? Like the fourth side of Welcome To The Pleasuredome, we are reminded that it’s only because

of “Never Gonna Give You Up” that we’re hearing this stuff at all.

The album’s most troublesome song is its last, and the one

which throws up all of the bothersome questions. Astley’s “When I Fall In Love”

is an attempted carbon copy of the Cole original, down to Gordon Jenkins’

arrangement (here reproduced on Fairlight, or Fairlights), and vocally is no

more than adequate. However, it is a strangely desolate piece of work, and one

is drawn to the unfortunate conclusion that had this been 1956, Astley would

have been out there dutifully covering American hits of the period. It sounds

like an attempt to erase the three

decades of uprising which separate the two recordings, a deliberate attempt to

go back to a time when rock hadn’t happened and singers knew their place.

The video is creepier still; Astley wanders around a

deserted, snowbound studio set, hanging out in front of, or inside, a log cabin

– there is no object of his love, only the camera, only us. There is in the

distance an arched bridge which could have fallen in straight from It’s A Wonderful Life. He looks as he

sounds; like a sad, small robot, lost in an abandoned world; I think of WALL-E and his endless viewing of

highlights from Hello Dolly, as if to

remind us that this was what humanity was once capable of creating. I do think

of a George Bailey who kills the world by never taking any risks. And last week’s

Pick Of The Pops was a timely

reminder of what such a world – this world which so many people in Britain

supposedly desire – would actually be like.*

*An interlude here about radio comedy, mainly because I

listened for a bit to BBC Radio 4Xtra on Wednesday evening. Some art doesn’t

transcend its time, and may not even have been art. Was there ever anything

remotely funny about The Navy Lark? I

listened to what sounded like the first episode of the second series – from September

1959 – and it was creakily unfunny, a prematurely tired set-up with mirthless

non-development. Stephen Murray’s Commander (“the new Number 1”) was so

bumbling and anonymous, one forgot he was there most of the time. Leslie

Phillips, as he has always done, played himself. Ronnie Barker and Michael

Bates were wasted. A little of Jon Pertwee’s gurning gurgle – he sounds as

though warming up to play Worzel Gummidge – goes an awfully long way (with the

emphasis on “awful”). And yet the series ran, unchanged in any detail, until

the era of punk. What was the attraction? Moderate pleasure giggling at a

fundamentally inefficient British way of doing things?

A May 1966 episode of I’m

Sorry I’ll Read That Again followed, and was as bad, if not worse. Given

what most of its participants went on to do, this was thin stuff indeed, like a

bad student revue where sound-effects and silly voices are allegedly funny in

themselves…and with a thick dollop of misogyny, laid on with such relish that

one marvels that Jo Kendall didn’t just hit the rest of the cast over their

heads with a spiky baseball bat for the full half-hour. Derek Bailey was in the

studio band, and wisely kept his head down. As regards “When I Fall In Love,”

its best use in 1987 was as a scratchy introduction to Pop Will Eat Itself’s “There

Is No Love Between Us Anymore,” which more or less could be construed as

everything Rick Astley wanted to say, but couldn’t, or wouldn’t.