(#356: 14 November 1987, 1 week)

Track listing:

Faith/Father Figure/I Want Your Sex (Parts I & II)/One More Try/Hard

Day/Hand To Mouth/Look At Your Hands/Monkey/Kissing A Fool

The other day I asked about the English attitude towards

pleasure – is there a book on it, or an essay?

I got one reply back about it being a rather “short pamphlet,” and

(having lived here for six years) I had to sadly agree. The English like “fun” but kind of mistrust

the intensity and expansiveness of “pleasure.”

Being an American here is to be surrounded by people (this is a

generalization, I realize) who were only encouraged to have fun, not to

discover what really pleased them, something gratifying and rewarding and

something they would like to share, not hoard; joy is for Christmas or a Bank

Holiday, ultimately only for just about a week or so a year (birthday

included). I may come from a nation

“founded” (cough) by the puritanical Pilgrims, but “life, liberty and the

pursuit of happiness” are in the US mix, as well.

That is a burden, sure, but it is also a right (I believe)

and it makes up a lot of the raw qualities of the US, for better and indeed for

worse. It is a complex fate to be an American,

but it is to be English too; the repressiveness and sense of alienation I feel

here in the UK comes and goes, and I can only wonder how young Georgios Kyriacos

Panayiotou in Bushey felt as the child of immigrants growing up in the

70s; his audacious leap into stardom has brought him here to 1987 and his first

solo album, since Wham! ended in 1986. I don’t know too much about him, but it is

clear to see here he too is fascinated by the US and caught up in the mechanics

of his own pleasure, within a society that will (and did) repress that need.

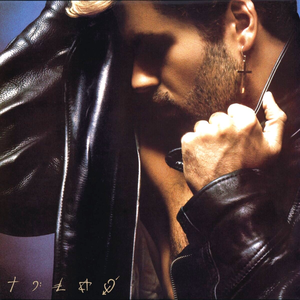

Which is to say, here is George Michael reaching out to the

US, making music that is inspired by American music, and of course America took

him on as one of their own (in Popstrology 1988 is the Year of George

Michael). Whether they were really

listening to him all that closely I don’t know (whether they are listening to

future Then Pay Long star Sam Smith all that closely I don’t know, either). If Michael is being cagey or elusive in

interviews around this time, it’s because (in hindsight) he is trying to appeal

to everyone with this album, still expected to sell tons by his record label

Epic, to take these very personal statements and make them – via tours and

videos – very very public. As you can

see from the cover photo, Michael is (unlike Jackson) trying to hide, to protect

himself, already saying, before you can hear the album, that this is all you

are getting; there are parts of him that will always be (or have to be)

reticent, held back…English, if you like*.

Of course, there were other reasons for Michael to be cagey;

drop yourself into 1987 and find yourself in a world of Section 28, a world

where “It’s A Sin” can get to #1 but it’s still a huge deal for Princess Diana

to be seen touching someone who has AIDS**. My chronology here may be a bit off, for reasons that will become apparent, but it's no surprise that Michael essentially is playing a shell game with Faith; beautiful and hard to crack, vulnerable and (needlessly, I think) tough.

One of the reasons Faith did so well is precisely because of this mysterious tension in the album - a sense that while Michael is being open, he, well, isn't really completely forthcoming. This is a New Pop strategy, saying something ("signifying" as it's called) without actually saying it. It's not something that started with New Pop - anyone who hears Martha and the Vandellas' "Dancing In The Street" or especially "Nowhere To Run" will know that pop can and does say more than one thing at one time, that the snow tire chains on the latter song aren't just there because they sound good. Ahem.

Faith starts with the title track, with Michael coming off all 50s Bo Diddley by way of Marylebone, leather jacket, blue jeans, designer stubble, and that signifying earring - a gold cross. That and a bit ol' acoustic guitar and it's all hello rock and roll, my name is George Michael, how are you? But he's not about gurning guitar solos or heavy growls; "Faith" is light, percussive, relentlessly on the beat and as upbeat as it sounds, it's about what most of this album is about: rejection. The Other (it is left to us to figure out who it is) wants him, but he is being self-protective, having been a victim of the "games" of another who had dumped him - "games" that he plays too, he admits, but now he wants something more, an "ocean" of a love that will not leave him on the floor, gasping and flailing like a fish caught on a line. He has been "foolish" before and is showing his potential Other the door, as he has to have, yes, faith. What he wants is more than just to touch someone else, more than just physical.

From this zippy beginning the album slows down immediately to "Father Figure." My objectivity about this, because of the time, is about zilch; my own father was very ill at the time, and thus any song where someone wants to be a father to someone else (and it's impossible for me to figure out if Michael is singing this as if he wants one or wants to be one or is one; it is a patient song though, that's obvious enough) was never going to wash with me. The shift, I can tell, was probably already happening inside me; that terrible gulf of no-father was becoming more and more clear, with no real person to fill it. George Michael singing this didn't exactly help much, as the gap between life and music began to become more elastic, less predictable. (It kind of goes without saying that I didn't really pay much attention to Michael at the time; he was there, he was popular, but he was merely there - not liked, not disliked, there.) And so I can listen to "Faith" and give it a thumb-up, but "Father Figure" seems big and intimate and distant and hopeless/unbelievable. Good, sure, but I somehow can't take it to my own heart, for obvious reasons. And what is the "life of crime" that the narrator is trying to avoid or escape? The song is all about someone wanting the Other in a physical way (so much for the previous song's rejection of physical love) but also as a "preacher, teacher" - that latter word will appear later - "anything" the other wants. It is as if this person isn't just a father but a mother as well - they are everything, and I guess this overwhelming need for someone to be all this for another/to need all this from another is too much for me; a bit suffocating...and yet it all floats by like a meeting of David Cassidy and P.M. Dawn, not oppressive at all.

From the Andy Gibb-all-grown-up of "Father Figure" (he just wants to be his Other's everything) the album goes into Holly-Johnson-breathing-all-over-the-keyboard of "I Want Your Sex." I don't know whether this was defiant or not as a song, but it's some nerve to write and perform a song that is about (as the kids put it back then) doing the nasty that is so direct and achy and slinky and unapologetic. The song was all but banned on normal UK radio, mentioned only as "I Want"; the UK attitude towards pleasure - sexual desire and urgency - being that pointless equivalent of the French eating a certain bird - an ortolan? - with a napkin on their head so God can't see them do it. But this song goes right to the issue - what is dirty? What does his Other consider pornographic? Michael sounds like someone who's just graduated and can't wait to show how great he is, how qualified - here he is, boys and girls, come and get him, he's beyond ready, now. None of these songs is addressed to either gender specifically, letting Michael fly under the radar (so to speak) of what I guess is called "heteronormative" radio. Sound enough like Prince and do a video with a girl in it and hey ho, beyond the ever-controversial subject of sex itself, then the line "there's boys you can trust/and girls that you don't" (as part of pt. 1) can be all but ignored, as Michael goes on to tell us (as if we didn't know) that sex is "natural" and "good." I'm not sure if the US needed to hear this, but in pleasure-phobic UK, maybe it was more than necessary? "I Want Your Sex" is just about desire for anyone, the kind that is near what in UK slang is "gagging for it." Oh Michael is all grown up now, there's no allusions anymore to dancing - he is throwing it right out there, as polite as he can be - trying to turn the NO! he's getting into a sighing, panting YES. (It doesn't happen, of course - even in pt. 3, which is tacked on here at the end, he's still trying to get his Other in the mood, via a "gin and tonic." Hmmm, don't know if that's going to work, George. Pt. 2 is all brassy confidence covering up anxiety, as he endlessly frets/praises over his Other, saying "I'm not your father/I'm not your brother." Which is to say, the single version is heteronormative, the others, less so.)

"One More Try" is the big ballad that shows what Michael is really capable of; it's (my guess) why it debuted at #1 on the Billboard R&B album chart, being the sort of song that again takes its time, but feels more solid than "Father Figure" - more of something that's been lived, fully experienced. He has been, yes, dumped; but he is "feeling the heat" in this new relationship, but has no need for yet more rejection; the narrator is an "uptown boy" who is willing, but wary...for his "teacher" to love him, educate him, and then dump him, figuring that's what the relationship is, fundamentally - a short course that leaves the narrator wiser but much sadder. All this to the ghost of "If You Don't Know Me By Now" and just as the song ends, the focus changes to the teacher, who is also alone, also damaged, but willing to give it "one more try" with this novice. The decision here is to be courageous, to say YES rather than NO, because trying is better than being alone. Again, in a world where people were basically told to keep themselves to themselves, to save their own lives, this need for the Other conquers all, including the persistent undertow of fear...

..."Hard Day" is about a relationship where the narrator (who clearly is out working) comes home and doesn't really want to hear about the Other's day; he just wants to have sex ("it's what we do best") with him/her, even though he isn't the one that this other loves the most. Again we have this aching lack of completion, and if he was impatient in "I Want Your Sex" then here he's angry, wanting his Other to trust him and love him back, not bring him down by not loving him, not making love with him. "DON'T BRING ME DOWN" he yells in all caps, he's already had a hard day and doesn't need more difficulties at home with a "sweet little boy" - or is this another reversal, with the Other calling him this? I don't know - and such ambiguity is how this album could do so well, could fit into the sonic lives of so many people.

So far so good; now, on to side two...

"Hand To Mouth" is the obligatory I'm-socially-conscious song on Faith; around this time, if you didn't have a socially conscious song on your album, you risked looking as if you weren't really grown-up. It's a feather-light song, musically, but looks at a world of violence, poverty, abandoned women, abandoned babies..."I believe in America" the narrator sings, but here is a cold and unfeeling place, where everyone lives hand-to-mouth; and there is the immigrant woman who has nothing left to lose "so she ran to the arms of America" - hello, The Joshua Tree - into a world of yes, faith but no gods, no one to rely on but yourself. The first side is about rejection (and longing for acceptance); this is social rejection and the same longing for a place, a place called America where freedom and love ought to be the laws of the land...but there is little happiness.

"Look At Your Hands" is one of the meanest songs I've yet to come across in Then Play Long; and yet as mean as it is, it is weak. The narrator once knew a girl who he loved, who didn't decide to stay with him; she is now the wife of a "drunken man" and the mother of "two fat children." He looks at her now with a combination of some (just some, not much) pity and a whole ton of contempt. That's what she gets for not wanting to be with him - a life of misery, one he taunts her about, telling her she can leave it and be with him, and then telling her he knows she won't do it. It's emotional abuse, pure and simple, any women's shelter could tell you that, and the narrator throws salt on this wounded woman's life with no real sense of empathy. He wants her, he claims she wants him, but she doesn't have the guts to leave her abusive husband - well smartass, why don't you take her and her kids (you don't think she's going to leave without them, huh? HUH?) down to that shelter and go take Feminism 101 to learn how these things happen in the first place. I rarely get angry with the narrators of songs - but here I do, and I can only look sideways to Michael and one David Austin (the only time Michael has someone help him write a song) and wonder just what they were doing, writing a deliberately spiteful and abusive song. Sign of the times? Hmmm....really, all it needs is Mick Jagger pointing his finger contemptuously to show how old-fashioned this kind of thing is. It's 1987, things are tough all over, and doing something like this to show you're "rock" is just dumb.

"Monkey" is about, yeah, junk, and if it sounds like a reworking of something by Janet Jackson (and, secondarily, Peter Gabriel's So) - well, I can imagine Michael did a lot of listening to Control while writing this. It just works; and here the Other has him/herself an Other that is a drug, and it's all tough love again - "do you love the monkey or do you love me?" being the main question. He doesn't know why the monkey is so hard to give up, but in his determination to keep bugging his Other he thinks he might get somewhere, the Other being fundamentally a weak person, weak enough to be swayed by his persistent begging and hectoring questions. Now the rejection isn't even about a rival but something that clearly provides his Other with something he can't give - hence the anger in the song, the rejection he gives the Other, who can't or won't give up. "Why do I have to share my baby with a monkey?" it ends, again showing that maybe he really doesn't know his Other as much as he thinks he does, as if s/he is "the best" and yet also mysterious and unknowable...hmm, maybe the Other is scared of something, as scared as the narrators of "One More Try"? (Also, hello Robbie Williams.)

From this funk attack the album slows right down and reverses out of rock altogether for jazz; the easy sway of a song that talks of hearts, hearts lost and found, the fundamental need - "to even make a start" you have to be true to your heart. True to yourself? Is the shell game ending, with Michael ready to say what he really feels? The song is sung to someone who the narrator has already had a relationship with, someone who was persuaded away from him - "You listened to people/who scared you to death/and from my heart/strange that I was wrong enough" - this all may be signifying, but it's also a story as old as the proverbial hills - two people attracted to each other, the one leaving the other because of what s/he is told by others, not by their own decision, and the rejected one feeling like a fool. The narrator is loyal, a man - a man who is dumped and yet still hopeful, no longer a figure who is an "uptown boy" but someone with some maturity and understanding that faith is not enough, but knowing your own heart and following it - however fraught with difficulties that may be - is the best, the only way through romance, through life itself.

It isn't much of a mystery to figure out why this did so well - something for literally everyone, with the songs so deliberately vague/slyly signifying that no matter who you were, there was something to identify with - from the 50s to the present and back to the 40s, from longing to aching to a kind of calm...his heart, once on the floor, is now where it should be, solidly within himself, as he can hold on to not just faith but also love itself - patience, if you will - and the last song sets the stage for his next album, as if Faith was just a stage he was going through - a wildly successful stage, but just a stage, nevertheless. The flood of fear and anxiety and lust is over, and he washes up on the shore of an ocean that is calm and luxe, still able to raise his voice as to how loyal and true he is, but then quietening down again to croon about being a fool, and maybe understanding that in all this he has been something of a fool too, pursuing the wrong people, the wrong goals. So, a happy (even, pleasurable?) ending of sorts.

It is too bad that I was in no state to hear this at the time, but I was undergoing my own flood, and that dictated its own fears and anxieties, ones that Faith wouldn't have been able to allay much at the time. The gap between hearing something and it leaping directly into my heart is very narrow now, for some music, and quite wide for others. The incomprehensible is happening every day, and that is warping and stretching what I can hear, how I hear altogether. But Faith stands as a near-perfect album of youth, young manhood, finding out what that oh-so-blithely-referred-to faith really means, which is mainly faith in yourself, and hence faith in others. And also - to follow your heart, your own sense of pleasure. That much, I would have understood even then, had I bothered to listen.

One of the reasons Faith did so well is precisely because of this mysterious tension in the album - a sense that while Michael is being open, he, well, isn't really completely forthcoming. This is a New Pop strategy, saying something ("signifying" as it's called) without actually saying it. It's not something that started with New Pop - anyone who hears Martha and the Vandellas' "Dancing In The Street" or especially "Nowhere To Run" will know that pop can and does say more than one thing at one time, that the snow tire chains on the latter song aren't just there because they sound good. Ahem.

Faith starts with the title track, with Michael coming off all 50s Bo Diddley by way of Marylebone, leather jacket, blue jeans, designer stubble, and that signifying earring - a gold cross. That and a bit ol' acoustic guitar and it's all hello rock and roll, my name is George Michael, how are you? But he's not about gurning guitar solos or heavy growls; "Faith" is light, percussive, relentlessly on the beat and as upbeat as it sounds, it's about what most of this album is about: rejection. The Other (it is left to us to figure out who it is) wants him, but he is being self-protective, having been a victim of the "games" of another who had dumped him - "games" that he plays too, he admits, but now he wants something more, an "ocean" of a love that will not leave him on the floor, gasping and flailing like a fish caught on a line. He has been "foolish" before and is showing his potential Other the door, as he has to have, yes, faith. What he wants is more than just to touch someone else, more than just physical.

From this zippy beginning the album slows down immediately to "Father Figure." My objectivity about this, because of the time, is about zilch; my own father was very ill at the time, and thus any song where someone wants to be a father to someone else (and it's impossible for me to figure out if Michael is singing this as if he wants one or wants to be one or is one; it is a patient song though, that's obvious enough) was never going to wash with me. The shift, I can tell, was probably already happening inside me; that terrible gulf of no-father was becoming more and more clear, with no real person to fill it. George Michael singing this didn't exactly help much, as the gap between life and music began to become more elastic, less predictable. (It kind of goes without saying that I didn't really pay much attention to Michael at the time; he was there, he was popular, but he was merely there - not liked, not disliked, there.) And so I can listen to "Faith" and give it a thumb-up, but "Father Figure" seems big and intimate and distant and hopeless/unbelievable. Good, sure, but I somehow can't take it to my own heart, for obvious reasons. And what is the "life of crime" that the narrator is trying to avoid or escape? The song is all about someone wanting the Other in a physical way (so much for the previous song's rejection of physical love) but also as a "preacher, teacher" - that latter word will appear later - "anything" the other wants. It is as if this person isn't just a father but a mother as well - they are everything, and I guess this overwhelming need for someone to be all this for another/to need all this from another is too much for me; a bit suffocating...and yet it all floats by like a meeting of David Cassidy and P.M. Dawn, not oppressive at all.

From the Andy Gibb-all-grown-up of "Father Figure" (he just wants to be his Other's everything) the album goes into Holly-Johnson-breathing-all-over-the-keyboard of "I Want Your Sex." I don't know whether this was defiant or not as a song, but it's some nerve to write and perform a song that is about (as the kids put it back then) doing the nasty that is so direct and achy and slinky and unapologetic. The song was all but banned on normal UK radio, mentioned only as "I Want"; the UK attitude towards pleasure - sexual desire and urgency - being that pointless equivalent of the French eating a certain bird - an ortolan? - with a napkin on their head so God can't see them do it. But this song goes right to the issue - what is dirty? What does his Other consider pornographic? Michael sounds like someone who's just graduated and can't wait to show how great he is, how qualified - here he is, boys and girls, come and get him, he's beyond ready, now. None of these songs is addressed to either gender specifically, letting Michael fly under the radar (so to speak) of what I guess is called "heteronormative" radio. Sound enough like Prince and do a video with a girl in it and hey ho, beyond the ever-controversial subject of sex itself, then the line "there's boys you can trust/and girls that you don't" (as part of pt. 1) can be all but ignored, as Michael goes on to tell us (as if we didn't know) that sex is "natural" and "good." I'm not sure if the US needed to hear this, but in pleasure-phobic UK, maybe it was more than necessary? "I Want Your Sex" is just about desire for anyone, the kind that is near what in UK slang is "gagging for it." Oh Michael is all grown up now, there's no allusions anymore to dancing - he is throwing it right out there, as polite as he can be - trying to turn the NO! he's getting into a sighing, panting YES. (It doesn't happen, of course - even in pt. 3, which is tacked on here at the end, he's still trying to get his Other in the mood, via a "gin and tonic." Hmmm, don't know if that's going to work, George. Pt. 2 is all brassy confidence covering up anxiety, as he endlessly frets/praises over his Other, saying "I'm not your father/I'm not your brother." Which is to say, the single version is heteronormative, the others, less so.)

"One More Try" is the big ballad that shows what Michael is really capable of; it's (my guess) why it debuted at #1 on the Billboard R&B album chart, being the sort of song that again takes its time, but feels more solid than "Father Figure" - more of something that's been lived, fully experienced. He has been, yes, dumped; but he is "feeling the heat" in this new relationship, but has no need for yet more rejection; the narrator is an "uptown boy" who is willing, but wary...for his "teacher" to love him, educate him, and then dump him, figuring that's what the relationship is, fundamentally - a short course that leaves the narrator wiser but much sadder. All this to the ghost of "If You Don't Know Me By Now" and just as the song ends, the focus changes to the teacher, who is also alone, also damaged, but willing to give it "one more try" with this novice. The decision here is to be courageous, to say YES rather than NO, because trying is better than being alone. Again, in a world where people were basically told to keep themselves to themselves, to save their own lives, this need for the Other conquers all, including the persistent undertow of fear...

..."Hard Day" is about a relationship where the narrator (who clearly is out working) comes home and doesn't really want to hear about the Other's day; he just wants to have sex ("it's what we do best") with him/her, even though he isn't the one that this other loves the most. Again we have this aching lack of completion, and if he was impatient in "I Want Your Sex" then here he's angry, wanting his Other to trust him and love him back, not bring him down by not loving him, not making love with him. "DON'T BRING ME DOWN" he yells in all caps, he's already had a hard day and doesn't need more difficulties at home with a "sweet little boy" - or is this another reversal, with the Other calling him this? I don't know - and such ambiguity is how this album could do so well, could fit into the sonic lives of so many people.

So far so good; now, on to side two...

"Hand To Mouth" is the obligatory I'm-socially-conscious song on Faith; around this time, if you didn't have a socially conscious song on your album, you risked looking as if you weren't really grown-up. It's a feather-light song, musically, but looks at a world of violence, poverty, abandoned women, abandoned babies..."I believe in America" the narrator sings, but here is a cold and unfeeling place, where everyone lives hand-to-mouth; and there is the immigrant woman who has nothing left to lose "so she ran to the arms of America" - hello, The Joshua Tree - into a world of yes, faith but no gods, no one to rely on but yourself. The first side is about rejection (and longing for acceptance); this is social rejection and the same longing for a place, a place called America where freedom and love ought to be the laws of the land...but there is little happiness.

"Look At Your Hands" is one of the meanest songs I've yet to come across in Then Play Long; and yet as mean as it is, it is weak. The narrator once knew a girl who he loved, who didn't decide to stay with him; she is now the wife of a "drunken man" and the mother of "two fat children." He looks at her now with a combination of some (just some, not much) pity and a whole ton of contempt. That's what she gets for not wanting to be with him - a life of misery, one he taunts her about, telling her she can leave it and be with him, and then telling her he knows she won't do it. It's emotional abuse, pure and simple, any women's shelter could tell you that, and the narrator throws salt on this wounded woman's life with no real sense of empathy. He wants her, he claims she wants him, but she doesn't have the guts to leave her abusive husband - well smartass, why don't you take her and her kids (you don't think she's going to leave without them, huh? HUH?) down to that shelter and go take Feminism 101 to learn how these things happen in the first place. I rarely get angry with the narrators of songs - but here I do, and I can only look sideways to Michael and one David Austin (the only time Michael has someone help him write a song) and wonder just what they were doing, writing a deliberately spiteful and abusive song. Sign of the times? Hmmm....really, all it needs is Mick Jagger pointing his finger contemptuously to show how old-fashioned this kind of thing is. It's 1987, things are tough all over, and doing something like this to show you're "rock" is just dumb.

"Monkey" is about, yeah, junk, and if it sounds like a reworking of something by Janet Jackson (and, secondarily, Peter Gabriel's So) - well, I can imagine Michael did a lot of listening to Control while writing this. It just works; and here the Other has him/herself an Other that is a drug, and it's all tough love again - "do you love the monkey or do you love me?" being the main question. He doesn't know why the monkey is so hard to give up, but in his determination to keep bugging his Other he thinks he might get somewhere, the Other being fundamentally a weak person, weak enough to be swayed by his persistent begging and hectoring questions. Now the rejection isn't even about a rival but something that clearly provides his Other with something he can't give - hence the anger in the song, the rejection he gives the Other, who can't or won't give up. "Why do I have to share my baby with a monkey?" it ends, again showing that maybe he really doesn't know his Other as much as he thinks he does, as if s/he is "the best" and yet also mysterious and unknowable...hmm, maybe the Other is scared of something, as scared as the narrators of "One More Try"? (Also, hello Robbie Williams.)

From this funk attack the album slows right down and reverses out of rock altogether for jazz; the easy sway of a song that talks of hearts, hearts lost and found, the fundamental need - "to even make a start" you have to be true to your heart. True to yourself? Is the shell game ending, with Michael ready to say what he really feels? The song is sung to someone who the narrator has already had a relationship with, someone who was persuaded away from him - "You listened to people/who scared you to death/and from my heart/strange that I was wrong enough" - this all may be signifying, but it's also a story as old as the proverbial hills - two people attracted to each other, the one leaving the other because of what s/he is told by others, not by their own decision, and the rejected one feeling like a fool. The narrator is loyal, a man - a man who is dumped and yet still hopeful, no longer a figure who is an "uptown boy" but someone with some maturity and understanding that faith is not enough, but knowing your own heart and following it - however fraught with difficulties that may be - is the best, the only way through romance, through life itself.

It isn't much of a mystery to figure out why this did so well - something for literally everyone, with the songs so deliberately vague/slyly signifying that no matter who you were, there was something to identify with - from the 50s to the present and back to the 40s, from longing to aching to a kind of calm...his heart, once on the floor, is now where it should be, solidly within himself, as he can hold on to not just faith but also love itself - patience, if you will - and the last song sets the stage for his next album, as if Faith was just a stage he was going through - a wildly successful stage, but just a stage, nevertheless. The flood of fear and anxiety and lust is over, and he washes up on the shore of an ocean that is calm and luxe, still able to raise his voice as to how loyal and true he is, but then quietening down again to croon about being a fool, and maybe understanding that in all this he has been something of a fool too, pursuing the wrong people, the wrong goals. So, a happy (even, pleasurable?) ending of sorts.

It is too bad that I was in no state to hear this at the time, but I was undergoing my own flood, and that dictated its own fears and anxieties, ones that Faith wouldn't have been able to allay much at the time. The gap between hearing something and it leaping directly into my heart is very narrow now, for some music, and quite wide for others. The incomprehensible is happening every day, and that is warping and stretching what I can hear, how I hear altogether. But Faith stands as a near-perfect album of youth, young manhood, finding out what that oh-so-blithely-referred-to faith really means, which is mainly faith in yourself, and hence faith in others. And also - to follow your heart, your own sense of pleasure. That much, I would have understood even then, had I bothered to listen.

Next up: The power ballad hits the UK, hard.

*The American female response to suppressed/held back

English guys is one of either intense curiosity and

I’m-sure-I-can-make-him-talk enthusiasm or

I-don’t-want-to-be-with-someone-who-won’t-communicate-openly harsh judgement, the

latter being the usual response when she finds out that he will talk but only

politely and not about himself. Then,

being American she will either give up or keep trying, particularly if he is

cute, a description I don’t think any Englishman would use to describe himself,

ever.

**The Queen was against this at the time, according to this link: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/1575119/Queen-was-against-Dianas-Aids-work.html

.jpg)